Chapter Eleven

“Yoganathan Is Dead”

After his diksha,Yogaswami immediately set out on pilgrimage to the South. Perhaps he sensed that his guru was severing the cord that had connected them so closely. Perhaps he remembered Swami Vivekananda’s pan-Indian trek following the death of his guru, Sri Ramakrishna. Or perhaps he simply took Chellappaswami’s words literally. For whatever reasons, he stood up and left the place. With only the clothes on his back, as a parivrajaka, “wandering monk,” he set out on a pilgrimage to Kataragama, Lord Murugan’s shrine in the remote south of the island. He told no one he was leaving. §

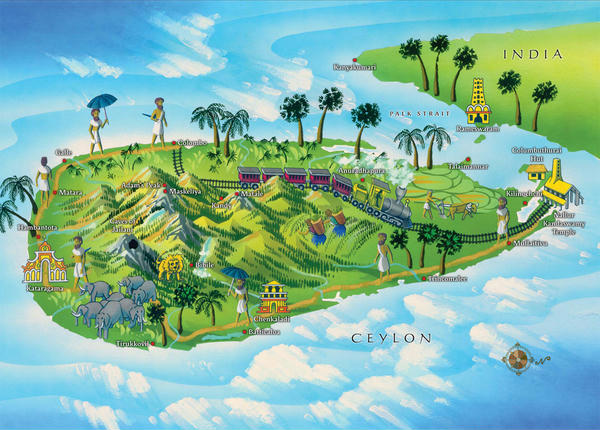

Circling Ceylon on Foot

He walked along back roads and country paths, proceeding east to the coast, then south to Mullaitivu and beyond, going where he pleased, stopping often at shrines and temples to meditate for hours or days. He walked along the coastal belt that skirts the eastern region, through Trincomalee, Sittandi, Batticaloa, Tirukkovil and Pottuvil. With no place to be next, nothing to do, he strolled the roads through towns and valleys like a monarch in his private garden. §

His practice was to see himself as everything, and everything as himself. Life flowed gracefully through him and around him—everything came of its own accord. He didn’t need to plan or calculate. There was always a hut or a temple devasthanam waiting for him at the end of the day. When he was hungry, someone was there offering him food or inviting him to their home for a meal. He had nothing to do but his inner work, and wherever he found himself he went in and in and in. §

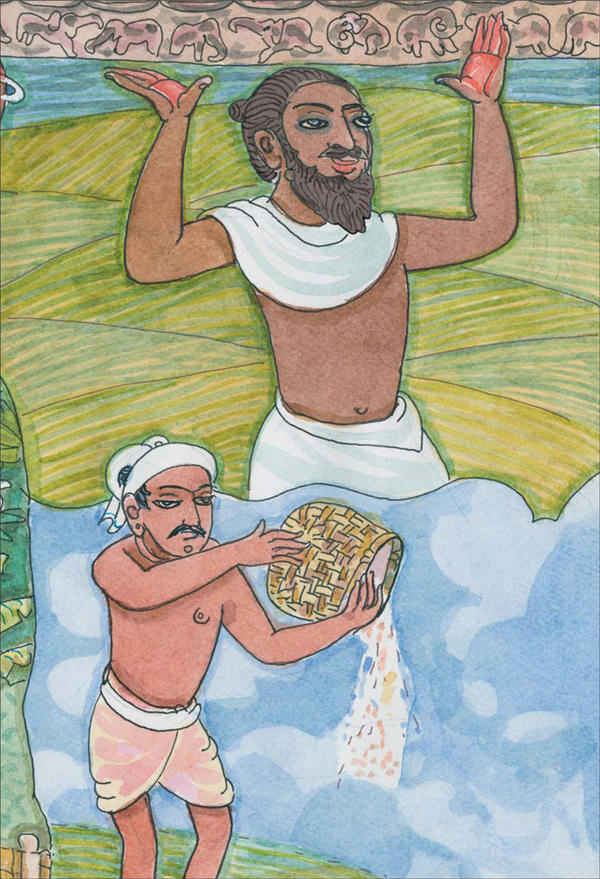

Swami was a silent witness to the agrarian life that occupied most of Lanka’s people in those days. Farming and fishing were the mainstays, along with celebrations, festivals, trials and tribulations. He saw a beautiful world filled with Siva, where everyone did their work and where everything is as it should be at every point in time. And all he saw he took as his own. The passage of life before him was instructive, contrasting as it did his own renunciation. §

And Chellappaswami made no decree. This was a deeply inner pilgrimage, a time of reorientation after Chellappaswami’s unexpected severance of their almost daily companionship. Yogaswami had to redefine his life in light of his guru’s decree. All along the way, he prepared the ground for the work he would do in his lifetime, developing intuitive powers and immersing himself again and again in the Self, the Absolute Reality that was his formless home. §

The majority faith on the island was Buddhism, then as now, and he encountered Buddhist people frequently during his travels, something that had rarely happened in the Hindu-majority North where he had lived his entire life. In later years, when Buddhists came to see him, he often spoke to them like a bhikku, quoting verbatim from Buddha’s sermons. §

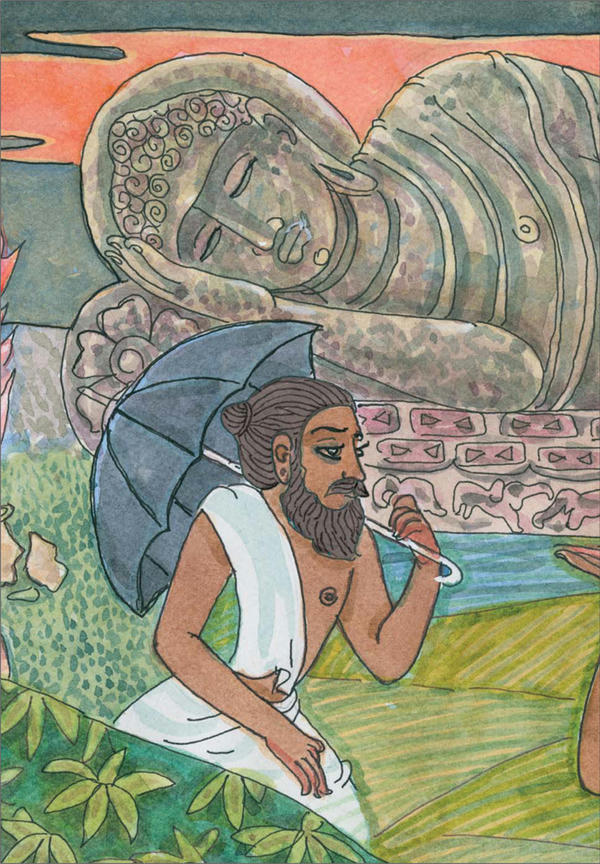

Yogaswami visited Polonnaruwa, 140 kilometers north of Kandy, where the famed 46-foot-long reclining Buddha rests. It is said the carving depicts the moment Buddha entered nirvana.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •§

On this pilgrimage, Yogaswami embraced the whole of Ceylon from the inside out. He fell in love with its tropical splendor, its geographical beauty and its human diversity. He saw and heard everything people did on his estate and ever after spoke of “my island,” “my people,” “my saints and sages.” §

In later years, if one of his devotees had some business to do with the government, Yogaswami would assure him, “No need for concern—my government, my Prime Minister, my Finance Minister.” He sang: §

Lanka is our land! There is no male or female, no sameness or diversity. Heaven and earth are one. This is the language of the great! Come now and be happy; we will rule the world! §

If a man came to Yogaswami for blessings, having been transferred to some far-off province, Swami would tell him about the temples and shrines in that area. He knew the land, the legends and local people like he knew his own village. He would describe the shrines to visit, when to go and what kinds of prayers to offer. “I meditated there for several days,” he would say. “You must go there often.” Only gradually, through the years, did the great range and depth of experiences that his pilgrimage brought him come to light. §

It was two months before he reached Kokkilai. He was in no hurry. Two weeks later he was in Trincomalee. From there he went inland to the hill country, to Polonnaruwa and Sigiriya, then out again to Batticaloa. He met many holy men along the way—saints, sages, fakirs. He sat with yogis living deep in the jungle or in caves in the hills. He visited Buddhist monasteries and met Sufi saints and Christian clergy. Everywhere, he felt at home; everywhere, he was welcomed. §

On the road one day, he met a Muslim holy man. They walked together through the afternoon, and before they parted the saint sang for him a song in praise of God of such purity and beauty that Yogaswami never forgot it. He sang it often throughout his life. When he did, he would describe this saint to his devotees. §

Near a crossing of the Gal Oya River he came upon seven fakirs who lived in huts in the jungle, practicing austerities to gain yogic powers. They invited him to join in their psychic pursuits, and performed several tricks to entice him, but he did not accept. A moment later, they materialized a huge, wild boar. Squealing and frothing, it charged straight at him, blood dripping from its jaws—he didn’t have a chance to save himself. He didn’t flinch; neither did he steel himself. He watched; and just as the beast barely touched him, it vanished as quickly as it had appeared. He thanked them for the fun and continued across the river. §

Passing through a Muslim village in the Batticaloa district, he encountered an Islamic mystic named Thakarar who had divined Swami’s inner thoughts and, desiring to honor the wandering holy man, invited him to a feast. Seeing the Hindu monk hesitate, he asked if he had any conflict with Islam. Remembering Chellappaswami’s aloofness to caste and creed, Yogaswami joined the feast. Later he reported that, contrary to Islamic practice, the women joined with the men in hosting him. Thakarar gave him a bangle, saying, “Wear this amulet and go. You will not incur any difficulties.” Years later Swami spoke of that incident: “So long as that bangle was on my wrist, the Muslims treated me very respectfully. One night I removed it and left it in the rest house where I stayed, thinking, ‘Why do I need this?’” §

Near Tirukkovil he met a lone fakir who lived in a cave. Taking shelter from the rain, they sat and talked for several hours. As Swami prepared to leave, the fakir presented him with a magical tin can, a symbol of what he had accomplished in the eleven years he had lived there. He told his guest, “Keep the can, and everything you want will miraculously come to you.” Yogaswami graciously accepted the gift and went on his way. As soon as Swami was out of sight, he threw the can away. §

In mid-July, about six months into his journey, Yogaswami reached the southern coast and began the trek inland to Kataragama—120 kilometers on harsh and difficult trails through the dense jungle of the Monaragala and Bibile area, which is home to the aboriginal tribe known as Vedda. §

Yogaswami later narrated to Vallipuram, a schoolteacher in Jaffna, his experience about some of the trials he faced, which S. Ampikaipaakan captured in his biography:§

I was walking towards Kataragama, and as I was approaching Mattakalappu suddenly I got fever. I could not bear the pain, so I rested underneath a tree and lay down on the ground with a stone as a pillow. In the morning the fever was gone, and there was a 25 cent coin on the stone pillow. I took that to a store, ate dosai, and continued to walk. Anaikutti Swami (perhaps Sitanaikutti Swami) saw me on the way. He came running and embraced me, saying, “Because I saw you, it will rain now.” I responded, “Let the rain come after one hour.” It rained indeed after one hour. §

Later on the way I had to cross a river but it had flooded. Unable to cross, I made a shallow furrow in the riverbank sand and slept for three days. On the third day, some natives came to this side of the river on a catamaran. They cooked food for me and called, “O fasting nobleman,” to wake me up. They fed me a meal and took me to the other side of the river with them in their boat.”§

Soon the trail was crowded with thousands of devotees on their way to Murugan’s shrine for Esala Perahera, the annual fourteen-day festival that ends on the full moon night of July-August. Each devotee carried a bundle of supplies: food, camphor and simple bedding. Yogaswami carried only a coconut, the traditional offering every pilgrim brings. He slept in the open and ate nothing for the three days it took to reach the remote shrine. There he spent most hours of the night on the sacred hilltop in meditation and communion with Lord Murugan, and the daytime hours around the jungle shrine and ashrams.§

Meanwhile, Yoganathan’s relatives in Jaffna, frantic over his long absence, were making every attempt to find him. He was a sannyasin, so they were used to not seeing him for weeks at a time, but he had never left them for so long. Family ties are strong in Jaffna, and people keep track of one another no matter what they decide to do with their lives. Finally, after postponing it as long as he could, Chinnaiya arranged with one of Chellappaswami’s oldest devotees to accompany him to Nallur. He thought perhaps “the mad one” might know the nephew’s whereabouts. §

They found Chellappaswami sitting alone on the teradi steps weaving fans, talking. Watching them come up the street, he put his work aside. They apologized for disturbing him, praised his fans, remarked on the weather, hemmed and hawed and then nervously asked their question, “Where is Yoganathan? We have not seen him for months.” Chellappaswami shrugged and went back to weaving: “Oh, Yoganathan. He’s dead.” Realizing there was nothing more to that conversation, the family left in dismay. Badly shaken by the news, they tried to disbelieve it for a long time. Aunt Muthupillai took it especially hard. They waited several months, hoping Swami would appear, but they finally gave up; their nephew was gone. They performed what funeral rites they could without the body, and disposed of his personal effects. §

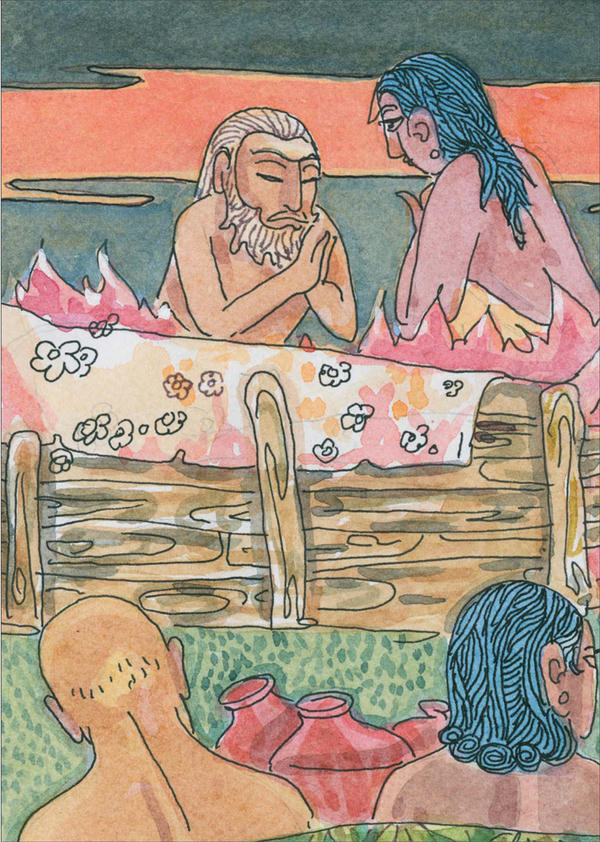

Yoganathan’s aunt, Muthupillai, was shocked when Chellappaswami told the family he was dead. They held his funeral rites, only to later discover he was in fact alive.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •§

Meanwhile, Yogaswami was wandering about the isle of Lanka, seeing everything for the first time. He said all his life that it was the finest of pilgrimages. Kataragama was all he had heard it to be. The spirit and power of the place at festival times is intoxicating. The shrine lies in a wilderness of nearly impenetrable jungle, but this only adds to its attraction. A sublime, solemn atmosphere hangs over this valley ringed by seven sacred hills. The name Kataragama is uttered with respect by Hindus, Buddhists and Muslims alike. §

Empty and quiet much of the year, Kataragama erupts overnight at festival times into the most intense activity, then ending as quickly as it started. Filled with thoughts of the mercy and power of the Deity, people regularly perform special penances, receive blessings, make promises, take vows and attain to spiritual heights that don’t seem possible elsewhere. §

Swami spent an unknown time at the jungle temple—a few days, some claim, while others believe it was months. Here, at the Murugan Temple, he performed meditation and practiced “being still” (Summa iru). Later he sang this brief song of praise:§

O Murugan of Kataragama, playing with your upraised spear, rid me of that foe, my karma! To you, with faith, I now draw near. Our Lord with foot in dance uplifted, who has an eye upon His brow, you, as our God, to us has gifted. At your feet with anklets ringed I bow. Everywhere your holy faces, your eyes, ears, hands and feet, I see. O Lord who Kataragama graces, wherever you are, there I will be!§

From Kataragama, Yogaswami headed west toward Colombo, following the coast, navigating through Magama, Hambantota, Matara and Dondra Head, Galle and Kalutara. He kept a leisurely schedule, walking through hundreds of villages, talking to people, watching life go on around him. He stopped less often here, for the South is a predominantly Sinhalese area, and there are only a few Hindu temples. §

Just as Swami Vivekananda explored his beloved India, Yogaswami’s 1910 adventure took him throughout the island, where he saw and celebrated the spirit of the people, the places of pilgrimage and the daily rhythms of life in Lanka’s villages and fields.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •§

He stayed every night in a different village, invariably as a guest in a Tamil home. During his six-week return journey, he underwent severe hardship, surviving only on alms, walking through jungles and facing wild animals. Due to flooded, muddy rivers, Swami often did not have proper drinking water and fell sick with malaria. With great effort, he rose each day to march another twenty or thirty kilometers, forcing his body to perform its duty, ignoring its complaints. §

Finally, with Lord Murugan’s blessings, he arrived in the Colombo district, the bustling port capital of Ceylon. There, on the road, he received the blessings of one of Lanka’s most renowned siddhas, known as Anaikutti Swami, “baby elephant,” by virtue of his generous girth. Reaching out his arm, the siddha handed the weary wayfarer five cents, saying, “This is the trunk [of Ganesha] giving confidence to you!”§

He stayed for a few days at Kochikade, where he begged for his meals and slept on the roadside along with the coal-handling railway workers. As a beggar, he approached the well-known Sir Ponnampalam Arunachalam, who gave him ten cents. §

He spent one month in and around Colombo, the island’s largest city, then several weeks inland between Kotte and Ratnapura. From there he took the rising roads to the mountainous town of Kandy and south to Nuwara Eliya, the hill country center of tea plantations. He walked along village paths and roads to Kurunegala and all the way to Puttalam, near the coast again. He stayed in Anuradhapura for several weeks, bringing all the threads of his pilgrimage together, then continued on toward Matale. §

The night before Swami arrived in Matale, Tiru Saravanamuthu, overseer of the town’s public works department, had a holy dream in which Lord Murugan appeared and instructed him, “Receive the saint who is returning by foot from Kataragama, famished and wearing tattered clothes. Give him all that he needs. Treat him well. We are one and the same. His return to Jaffna is a great gift to the people.” §

The next day Saravanamuthu met the mendicant who fit the description in his dream and, after inquiring as to who he was, invited Swami to his house with immense joy. He spoke excitedly about his vision as he practically dragged Swami inside. Yogaswami smiled, listened and let himself be hosted. Saravanamuthu gave him a new veshti and shawl and invited him to bathe. After a luxurious meal, Swami was shown the guest room, where he spent a restful, rejuvenating two days. §

In the background, peeking out at Swami whenever he had a chance, was Saravanamuthu’s nephew, a young boy who was so captivated by Swami’s darshan on that fateful day that he served him with utmost devotion his entire life. It was A. Thillyampalam, who four decades later Swami assigned as the architect of his Sivathondan Nilayams in Jaffna and Chenkaladi. §

Early in the morning of the third day, Swami decided to proceed the rest of the way to Jaffna by train. Declining the presents and a thick bundle of rupees his host urged on him, Yogaswami accepted just enough money for a train ticket. Yogaswami later remarked, “Lord Murugan was looking after me well through Saravanamuthu.” As a parting gesture of gratitude, Swami sang the following verse:§

Appanum ammaiyum neeye! Ariya sahothararum neeye!

Opil manaiviyum neeye! Otharum maintharum neeye!

Seppil arasarum neeye! Thevathi thevarrum neeye!

Ippuviyellam neeye! Ennai aandathum neeye!” §

Father and mother are you. Dear brothers and sisters are you. Incomparable wife is you. Precious sons are you. Royal potentates are you. The devas and all Gods are you. This great Earth is you; and that which guards and governs me is also you.§

Under the Illupai Tree

The train ride to Jaffna took two days: back through Anuradhapura, then north the next morning 190 kilometers to Jaffna Station. Yogaswami arrived as he had left nearly a year before—with nothing but the clothes on his back. He walked straight to Nallur Temple and threw himself at the feet of Chellappaswami. Having completed his travels, Yogaswami was fulfilled, exuberant, his heart overflowing with love for his guru. §

Now Chellappaswami gave his successor a new sadhana, “You go and hold the illupai root,” “Nee poy illupai verai pidi.” Yogaswami was not eager to leave his guru, and he lingered awkwardly. Seeing Chellappaswami’s clay meal pot which lay nearby, he thought, “What a great blessing it would be to have it as a sacred artifact.” Suddenly Chellappaswami roared like thunder and scoffed, “So, this is your bondage?” He threw the pot on the ground, shattering it into pieces, a gesture taken as Chellappaswami’s final sundering of the guru-disciple dualism that it represented to his shishya. §

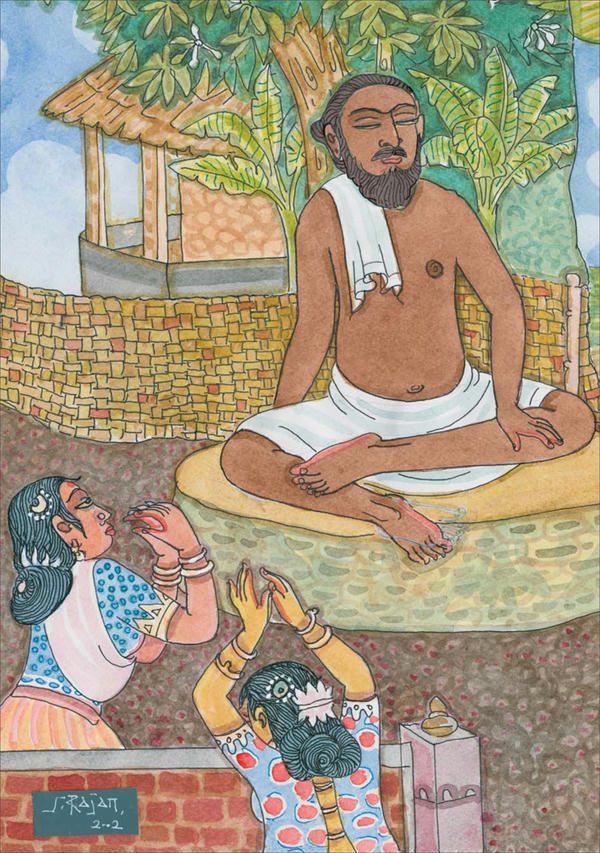

Following his guru’s edict, Yogaswami returned to Columbuthurai, taking his seat three meters from a road crossing, at the base of a mature illupai tree (Madhuca longifolia), a hardwood species prized for its fuel oil and medicinal attributes. Its shade and protection from the elements would be important for him in the years to come. In pounding rain or scorching sun he sat immobile, immersed in his inner being, oblivious to the outside world. A Pillaiyar temple stands just across the road. From that point onward, from 1911 to 1915, Chellappaswami did not allow Yogaswami to be with him. §

On one occasion Yogaswami visited Chellappaswami’s hut. Suddenly the sage emerged, shouting and swearing at him to get out of there. Realizing that his guru was about to start throwing things, Yogaswami turned on his heels and retreated the way he came. “Stand on your own two feet!” the sage bellowed after him. §

Chellappaswami would come to the illupai tree occasionally, observe his disciple and go. Once, when his guru came, Yogaswami stood up and went to worship him. Chellappaswami glared, scolding, “What! Are you seeing duality? Try to see unity.” Chastened by these words, Swami remained rooted to the spot. §

News travels faster than the wind in Jaffna. Before Swami had left Nallur Temple, his Uncle Chinnaiya and Aunt Muthupillai had heard from a dozen people about his reappearance. They were astonished, perplexed and happy all at once. They hurried to the illupai tree to see for themselves. There he was, in rapt meditation. They hardly recognized him at first; he had changed so much. They called out to him: “Yoganathan!” He did not answer, or even open his eyes. But it was him, alright. And he was very much alive. §

They talked the matter over with friends and neighbors late into the night and decided that Chinnaiya, Muthupillai and her son Vaithialingam would return to the tree at dawn to speak with Yoganathan. When they arrived, he was still deep in samadhi. They left a tray of fruit for him and set off for Nallur by bullock cart to confront Chellappaswami again. §

Chinnaiya ranted all the way about how strange and cruel it was for Chellappaswami to tell them their nephew was dead. He was bold in approaching the sage this time. He complained that they had conducted Yoganathan’s funeral and finished the period of mourning, only to find he actually wasn’t dead at all! They resented the lie. “How could you say that?” Chellappaswami rode out the storm. Holding his ground, he retorted stoically, “What I told you was not a lie. Yoganathan is dead.” §

That enigmatic response, delivered with such calm finality, left them speechless. Knowing that further discussion would be useless, they shook their heads in dismay and left. Pondering the sage’s words for a long time, they slowly began to understand that he was referring to a spiritual transition rather than a physical one. With Chellappaswami’s insight unfolding inside them, they perceived for themselves in the weeks and months ahead that, indeed, their nephew was a different person. And with his puzzling ruse, Chellappaswami had magically severed all remaining attachment they had for Yoganathan. He had renounced family life, and they had been forced to renounce him. §

For years Yogaswami followed the difficult sadhana of meditating for three days at the base of an illupai tree in Columbuthurai. On the fourth day he would rest and move about, before returning for another round. In 1921, devotees cajoled him into taking up residence in a nearby thatched hermitage.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •§

Adopting a Humble Hut

For some years Yogaswami made the illupai tree his preferred place of sadhana, his roofless roadside hermitage. Those who were alive in those days told of how he sometimes looked out from fierce eyes that struck people with terror. If anyone dared approach—and few did, they were so afraid—he would grab a stick and chase them away. When not immersed in his spiritual disciplines, he would wander the area around Jaffna and visit his favorite sites. S. Ampikaipaakan shares: §

For a long time Swamigal never went far from Jaffna after he came back from His walking pilgrimage to Kataragama. Swamigal used to say, “I don’t have permission to go out of Jaffna Bay.” As far as we know, only after 1928, Swamigal used to go to Kandy and Colombo. He took those journeys for the benefit of devotees living there. The advocate M.S. Elayathamby used to accompany him. Swamigal considered that he was the right person.§

Just a year before Chellappaswami’s mahasamadhi, Yogaswami moved into a hut in the garden of a home near the illupai tree. This hut, which would be his humble ashram for the next fifty years, was tied to the history of Nanniyar, the man who welcomed Kadaitswami on the island of Mandaitivu when Swami first arrived in Ceylon. Nanniyar had let Kadaitswami stay in this very hut, became a staunch devotee and maintained a shrine for the guru.§

In Chellappaswami’s day, Nanniyar, a large, muscular, slow-witted fellow, used the hut as a tea shop, not far from his temporary home in Ariyalai. He was devoted to Chellappaswami as well, but the sadhu ignored him, as he ignored everyone, whenever the shopkeeper came for blessings. Nanniyar remained determined to get what he wanted. §

One day when Chellappaswami was walking by his shop, Nanniyar, drunk at the time, rushed out, grabbed the guru and dragged him, kicking and screaming, to the compound behind his shop, tied him to a post and threatened him with a knife, saying he would not free him until blessings were received. To Chellappaswami’s horror, Nanniyar bathed him, managed to shave his head and with frenzied zeal conducted his guru puja, passing a flame of camphor before his captive to implore the master’s grace.§

All the while, Chellappaswami, not one to endure such things, protested vehemently in the strongest language—screaming, scolding and yelling for help. Finally, from inside her house on the same property, Mrs. Tangamma, the wife of Nanniyar’s landlord, heard the ruckus and ran outside. The scene was as bizarre as it was farcical. Others gathered to see what was happening, and together the group, which by that time included Yogaswami, untied the captive guru. Chellappaswami fled, bellowing as he retreated indignantly. Nanniyar, it seems, was satisfied and didn’t bother Chellappaswami again. In a way, Chellappaswami had met his match in Nanniyar. The guru, who had assiduously avoided being worshiped his whole life, lost on that day, and, as far as history knows, only on that day. §

In 1914, Tangamma and her family noticed Yogaswami spending day after day under the illupai tree not far from the now-vacant tea shop, which was just a simple hut with mud walls, cow-dung floor and cadjan roof. Swami was there nearly every day, despite the hottest sun and driving rains. It occurred to them to invite him to move into the hut. They waited for a good time to approach the formidable sadhu. For days they read the subtle signs and studied his expression to ascertain if maybe it was the opportune moment to present their idea. Finally, they did. §

Tangamma, her husband Thirugnanasampanthar, Tangamma’s uncle Vallipuram and his wife Nagavalli together approached Yogaswami. Tangamma spoke: “How much longer are you going to sit at this junction, Swamigal?” Gesturing toward the hut, she bravely offered, “This hut lies vacant. You can stay there as long as you like in peace.” Beseeching him with a pure and innocent heart, she recounted to Yogaswami the day Nanniyar had captured and worshiped Chellappaswami on that same spot and submitted how great a blessing it would be to the family if he would stay there now. He could make it his ashram. Everything he wanted and needed would be provided. They would see to his needs and stay out of his way when he wanted solitude. They referred to Nanniyar gingerly because, in a sense, they were trying to do the same thing he had done with Chellappaswami. §

Yogaswami refused the offer for a time but finally relented, conceding he could use the hut when he was in Columbuthurai. From that day onwards, Tangamma, her son Tirunavukarasu, Mrs. Tirunavukarasu and their children performed selfless service to Yogaswami and all who visited his ashram. This humble hermitage became his abode until the day he attained mahasamadhi.§

Many times during his life Swami declared, “I’m going away and not coming back to this place.” Three or four days later he would be back. He once said, “Chellappaswami would not let me leave this place. He sent me back.” He laughed, “Nanni’s devotion to the guru has captured us here.” He often spoke of it as “Chellappaswami’s hut.” §

“A Miracle Will Happen Here Tonight”

In 1915, at age 75, Chellappaswami fell ill. When he developed a cold and consequent inflammation of the joints, his relatives treated him with herbal baths. He was sick for about two weeks. During that time, Yogaswami did not go to see him. That upset the devotees who were looking after Chellappaswami. For several years Swami had, from their point of view, been pushed to the outside of any circle gathered around Chellappaswami. Of course, his disappearance was by decree of his guru, but not all acknowledged that. Knowing that Chellappaswami was nearing the end of his life, they pestered Yogaswami to go see him, perhaps expecting some dramatic exchange that would indicate without a doubt that it was Yogaswami whom Chellappaswami had initiated as the guru to follow him.§

One day, out of deepening concern, Yogaswami did go to Chellappaswami’s hut. As Swami neared the compound, Chellappaswami roared, “Yuuradaa padalaiyil?” (“Who is at the gate?”), words not unlike the satguru’s first statement to him, “Who are you?” Then he shouted, “Paaradaa veliyil ninru” (“Stand outside and be a witness”). §

Obediently, Swami left the compound and walked back to his hut. Intently aware that nations around the globe were locked in the bloody battles of World War I, Yogaswami reflected to others, “Many are the kings who are dying now,” among them his spiritual king lying at death’s door. Two days later, in the month of Panguni (March-April), on Ashvini nakshatra, the illumined sage and spiritual giant Chellappaswami attained mahasamadhi. §

That morning he had told a neighbor who looked after his needs, “Tonight a great miracle will take place in this hut. Will you come?” But the neighbor did not go that night. The next morning he found Chellappaswami on the ground at the door to his hut. He had left his body in an unusual pose, one finger in his mouth and his legs frozen in a posture resembling Lord Nataraja’s blissful dance, called ananda tandava. His Grand Departure that day was as strangely wonderful as his life had been.§

Chellappaswami invited people to his hut in 1915, telling them that “a miracle will happen tonight.” That miracle turned out to be his Grand Departure. His body was cremated the following day.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •§

Earlier he had ordered that his body be cremated, knowing that some would insist on interring him in a samadhi chamber, as is often done for enlightened saints and sages. His devotees carried out his instructions, scattering their guru’s ashes in the sea at Keerimalai.§

Without Chellappaswami, his followers felt helpless and lost. Many became despondent, discouraged. Everyone noticed that Yogaswami was not present for the last rites. Two of the men who helped with the cremation went drinking afterwards. The alcohol inflamed their anger toward Swami and made them bold enough to confront him. They gathered up their courage as they entered his compound, then one called out, “Our guru has left his body, and you did not even see fit to join us in our final respects to him!” §

Yogaswami suddenly appeared in the doorway of his hut, picked up a stick and chased them out his gate and down the road. Running at full tilt, they took a turn into the village headman’s yard and dove headlong into a stack of hay to hide. Yogaswami had since gone back to his evening. But their adventure was just beginning. §

As they waited a moment until the coast was clear, suddenly the hay caught fire. They were both smoking cigars! They jumped up and scrambled to put out the fire. Neighbors came with buckets of water and extinguished the flames. The headman turned the two culprits over to the constable, and they spent the night in jail. §

Such was Swami’s inscrutable way. These men, like others who thought as they did, had no idea of what was going on in Swami’s mind. He fully lived the spiritual life that pandits only talk about. He knew the secrets of life and death, knew that Chellappaswami was still very much aware in his inner world, that subtle world of light. Death was no end to things. He had simply discarded his old, used-up body. §

That evening Swami sat in deep communion with his beloved guru, just as certainly as when they shared the bilva tree’s shade at Nallur. Why attend the funeral? He had received no inner orders to go, and in fact Chellappaswami had asked him to stand apart. He was not one to do anything simply because social propriety dictated it. T. Sivayogapathy relates: §

In the same spirit, Yogaswami never encouraged anyone to build a memorial ashram to his guru. Instead, he told his devotees to go to Sivathondan Nilayam meditation hall and meditate with devotion to enjoy the darshan of all gurus of the lineage. Yogaswami propounded: “Remain in one place with devotion,” “Onrai patri ohr ahatheh iru.” Hence, no shrine was built for Chellappaswami during Yogaswami’s lifetime. Later, devotees in the Nallur area built a simple shrine honoring the sage within the hut where he had lived and attained mahasamadhi. In 1982 Satguru Sivaya Subramuniyaswami had the hut rebuilt as a small, temple-like structure, with concrete walls and metal roof. After that, hundreds of people gathered there on special days, in the shadow of Nallur Temple, to sing the glories of the Kailasa Parampara.§

God Realization

In the last half of 1915, in the wake of Chellappaswami’s great departure, Yogaswami threw himself into a pattern of intensive sadhana. With his back to the giant illupai trunk, he would fast and sit in samadhi for days at a time. He slept without appearing to sleep, and on occasion it was noted that he spent nights meditating in the Columbuthurai cemetery, a common habit of the siddhas and Nathas. Of this spirit of renunciation he later wrote: “Let go the rope! Just go about here and there. See everything. Be a witness. Die before you die!” §

Dr. T. Nallanathan, a strong Saivite and a close devotee, recalls Swami’s comments to him about that period: §

It was in 1922 that Swami told me for the first time how he attained God consciousness. His sadhana was indeed very strenuous. In a week, the first three days and nights would be spent in nirvikalpa samadhi; the fourth day was the only free day in the week, when he would have some food and talk to friends. The next three days and nights again he would be immersed in nirvikalpa samadhi. The culmination of this strict and strenuous sadhana was sayujya samadhi, perpetual God consciousness, even in the waking state. At the end of six months the heavenly joy temporarily disappeared and the mundane consciousness was indeed a step lower down. He gave up his regular sadhana and since then let this God consciousness trickle down to his physical brain in a natural way. §

Yogaswami had joined that most elite of all groups, a handful of souls in each historical epoch who have realized Parasiva, the Absolute, the Self of all. Those who have had, and continue to have, the experience of Self Realization cannot explain it. Anything they say about the Self God does not satisfy them as true. Since the Self is beyond the mind, beyond even the most pure and refined state of consciousness, it is impossible to use the language of the mind to convey it. Most realized ones talk little about that experience, which is not an experience at all. One can feel them as different; the space around them is charged. Somehow they are not in the world in the same way that other people are. That darshan emanating from them is regarded by a Saivite as the truest guide on the path. The devotee opens himself more and more to the darshan of a great soul and, no matter where he is on the path, it carries him within. §

Yogaswami’s disciple, Sivaya Subramuniyaswami, who was not yet born, would later attempt a description of that ineffable reality:§

The Self is timeless, causeless and formless. Therefore, being That, it has no relation whatsoever to time, space and form. Form is in a constant state of creation, preservation and destruction within space, thus creating consciousness called time, and has no relationship to timelessness, causelessness or formlessness. The individual soul, when mature, can make the leap from the consciousness of space-time-causation into the timeless, causeless, formless Self. This is the ultimate maturing of the soul on this planet.§

The inmost center of consciousness—located only after the actinic forces dissolve concepts of form and even consciousness being conscious of itself—is found to be within the center of an energy-spinning force field. This center—intense in its existence, [with] consciousness only on the perimeter of the inside hub of this energy field—vitalizes all externalized form.§

Losing consciousness into the center of this energy field catalyzes one beyond form, time, space. The spinning hub of actinic energy, recreating, preserving and dissipating form, quickly establishes consciousness again. However, this is then a new consciousness, the continuity of consciousness having been broken in the nirvikalpa samadhi experience. Essentially, the first total, conscious break in the evolution of man is the first nirvikalpa samadhi experience. Hence, a new evolution begins anew after each such experience. The evolutional patterns overlap and settle down like rings of light, one layer upon another, causing intrinsic changes in the entire nature and experiential pattern of the experiencer.Ӥ

Stories were told that after Yogaswami first realized the Self he jumped up and ran forty kilometers in jubilant celebration of the tremendous energy of that breakthrough. Slowly, Parasiva became home base to him, as he returned to that ultimate reality day after day, letting that realization penetrate and infuse every atom of his body, every facet of his mind. No longer was he an outer person going into the Self; he was an inner person coming out of the Self and then going back in again. He was that Self, the All in all, and so was everyone else, even if they were unaware of it. §

He came out of these spiritual reveries, walked, radiated the light that was so intense within him, and occasionally sat to write Tamil verses giving expression to his world of revelation and realization. In the years ahead he composed these profound verses in shrines and homes, and in the Columbuthurai Vinayagar Temple across the road from his illupai tree. He sang of his experiences in this Natchintanai:§

I climbed upon the platform of Omkara. There I saw nothing, Kuthambai; there I saw nothing, my dear. I was blessed with the bliss of sleep without sleeping. I remained summa, Kuthambai; I remained summa, my dear.§

Ego disappeared; happiness disappeared. I became He, Kuthambai; I became He, my dear. I have attained the flawless nishdai that ever stays unchanging. There is no “I,” no “you,” Kuthambai; There is no “I,” no “you,” my dear.§

I became like a painted image, Kuthambai; I became like a painted image, my dear, unable to say whether it is “one” or “two.” I attained the feet of the Lord, Kuthambai; I attained the feet of the Lord, my dear, which cannot be described in terms of “good” and “bad.”§

The Creator, Who is the Eye within the eye, I saw and rejoiced, Kuthambai; I saw Him and rejoiced, my dear. Whether macrocosm and microcosm are “one” or “two” I was unaware, Kuthambai; I was unaware, my dear.§

The six chakras and the five states of consciousness entirely disappeared, Kuthambai; they entirely disappeared, my dear. By seeing without seeing, the lotus feet I worshiped without worshiping, Kuthambai; I worshiped without worshiping, my dear. §