Chapter Ten

“You Haven’t Caught Me Yet”

Chellappaswami rarely spoke directly to anyone. He never once told Yogaswami that he was his guru; he never talked to him like that. But he trained him, and Yogaswami adjusted everything about himself—his thoughts and feelings, his plans, his speech, the way he dressed—to blend his mind perfectly with his guru and thereby catch his veiled instructions. §

Chellappaswami did the work without seeming to do anything. He trained Yogaswami to have one-pointed concentration at all times and took every opportunity to shatter even his most subtle habits and attachments—demanding his disciple’s whole mind, his undivided attention, every moment they were together, even if nothing was happening. With Chellappaswami there was no routine, no rest, no slacking. A day in his company was worth a year of regulated life. §

His constant babbling was not distracted chatter, but earnest, mindful statements—to him, anyway. Though he might repeat himself without apparent end or purpose, his voice and expression revealed the full force of his mind behind every word. It fascinated Yogaswami. Try as he might, he could never reconcile Chellappaswami’s resonant, measured tones and luminous glance with the seeming nonsense that poured from his lips. §

Yogaswami never tired of listening, for there would be a gem of purest jnana every so often amid the most whimsical prattle, priceless statements of supreme wisdom that only those close to Chellappaswami ever heard. Because he took in every word his guru spoke, sense and nonsense, Yogaswami caught these gems and used them purposefully to open his own inner mind. If these had been the only teachings Chellappaswami ever gave him, they would have been more than enough. In later years, Yogaswami passed these aphorisms on to his own devotees, calling them the mahavakya, or great statements, of his satguru. §

In his poetic legacy, Natchintanai, Yogaswami summarized the four most pertinent statements: “All is Truth. There is not one wrong thing. It was all finished long ago. We know not.” Yogaswami explained that these sayings, when reflected upon, penetrate the mind in such a way that they bring about profound insight into the mind itself. Such realization of the mind as an inherently dual and self-created principle leads, ultimately, through sadhana, to realization of That beyond the mind—Parasiva, the nondual Self, the Absolute. He told his closest devotees to use these sayings as keys to profound meditation. They are the deepest teachings that language can convey. §

Chellappaswami was an enigma wrapped in a disheveled veshti. Few realized that this solitary sadhu who mumbled philosophical adages to himself and cursed strangers was among the most illumined souls of the time.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •§

At a distance, Chellappaswami appeared to be just another sadhu around the temple. Only a few ever glimpsed the spiritual power and soul maturity he possessed. These became his staunch devotees, putting up cheerfully with any amount of ranting and mad talk. They knew it was not for them but was his way of chasing off the timorous and those who weren’t ready for what he had to offer. Chellappaswami was unmoved by being misunderstood. Yogaswami explained this in a song called “The Madman:” §

Clothed in rags, he stands in front of Skanda’s holy temple. On those who come and go before him, my little treasure, he will shower abusive language as it comes. “It is as it is. It is all a juggler’s trick,” he’ll say. He wanders here and there, my little treasure. You will see him seated near the chariot. §

No caste has he, nor creed. He will not talk with anyone, my little treasure. People say he is deranged in mind. Justice and injustice have no place with him; nor does he conform to any pattern, my little treasure. He goes about like one insane. No holy ash or pottu does his forehead bear. He will not utter what has once been said, my little treasure. He has passed beyond the gunas. §

He will not tell you to be calm and rid yourself of ego. He speaks in contradictions, my little treasure. Those hearing him will say he’s lost his wits. Chellappan, my father, in vulgar language will revile all those who pass by in the streets, my little treasure. They will say that he is mad. With lordly gait he roams from place to place. But all of those who notice him, my little treasure, treat him with ridicule and scorn. §

One report has him repeating again and again, “All the money in all the banks in the world is mine.” Once he was introduced to a body builder, a man proud of his physique. As the man flexed his muscles and bulged out his chest, Chellappaswami pointed at him and shouted, “That body is mine!” The man, who had spent years developing his physique, was baffled and deflated by the advaitic claim.§

Though his gruffness was what most who encountered him remembered, Chellappaswami was a free spirit. He walked about as though he owned the Earth and everything upon it, happy, radiating compassion and inveterately carefree, with a touch of regalness in his manner and his stance. He did not care to attract followers. He gave freely to all who were ready, accepting nothing in return. He worked in secrecy or not at all. His guise of madness, he confided, would spare him the curious, the magic-mongers and faint-hearted. §

Most of his devotees were householders. He initiated only two renunciate shishyas in his lifetime, Yogaswami and Katiraveluswami. There had been others, young men who recognized Chellappaswami as their guru and had been accepted by him, but not in the way Yogaswami and his brother swami were. His method was stern, but they always felt his underlying and never-spoken care. They knew they lived under their guru’s umbrella of grace. §

Chellappaswami held Yogaswami so still, so awake to every experience and lesson, that he was gradually carried deep within, living for months at a time in perfect harmony with his guru. His mind and heart filled with light; he lived in realms the Gods hold dear. He rarely slept. If he wasn’t with Chellappaswami, he was sitting alone somewhere, blissfully absorbed in the vast inner life his guru’s grace had brought him. Yet, the purifying scoldings never stopped. §

Chellappaswami harangued and swore at him for the least of faults, for no faults at all, taking everything away until nothing remained but the One Existence Chellappaswami knew. As long as Yogaswami possessed the least consciousness of anything other than That, of anything to get or give, to gain or lose, Chellappaswami would fume and glare. Just the sight of Yogaswami would raise the guru’s ire. He let him know, whatever he had done, it was not enough; it was never enough. Yogaswami sang of the great sage and their relationship in “My Master:” §

He is the master who bestowed the basic mantra’s secret. He dwells within the minds of those with loving hearts. Laughing, he roams in Nallur’s precincts. He has the semblance of a man possessed; all outward show he scorns. Dark is his body; his only garment rags. §

Now all my sins have gone, for he has burnt them up! All powerful karma kindled in the past he has dispelled. His heart is ornamented with the love of God. He shines in purity, as a light well-trimmed sheds lustre. On that day at Nallur he came and made me his. He made me to be summa after tests. §

Always repeating something softly to himself, the blessing of true life he will impart to anyone who ventures to come near him. And he has made a temple of my mind. All pomp of guise and habit he abhors. §

When devotees with great love come to worship, he’ll hiss at them and glower black as Yaman. Yet, artfully he drew me ’neath his sway. ’Twas he who made me; but if I approach him he will attack me—attack me without mercy. At me he’ll look, and many words he’ll utter. All aim and object did that look dispel! §

He would not allow me to form any mental image. He would not allow me to offer any service. He would not allow me to know what was going to happen. And yet this God ingeniously fulfilled my heart’s desire. To serve him was a pleasure, but he would not allow it. He would not let me know what his pleasure was. §

He would not permit the gaining of pleasurable siddhis. Yet, thus did he befriend me. How wonderful was that! He would say, “There is no wonder!” And those who came in awe and wonder he would not suffer to approach him; he left them in perplexity. But his own devotees he permitted to pay homage—that teacher of true wisdom! §

Enigmatic Lessons

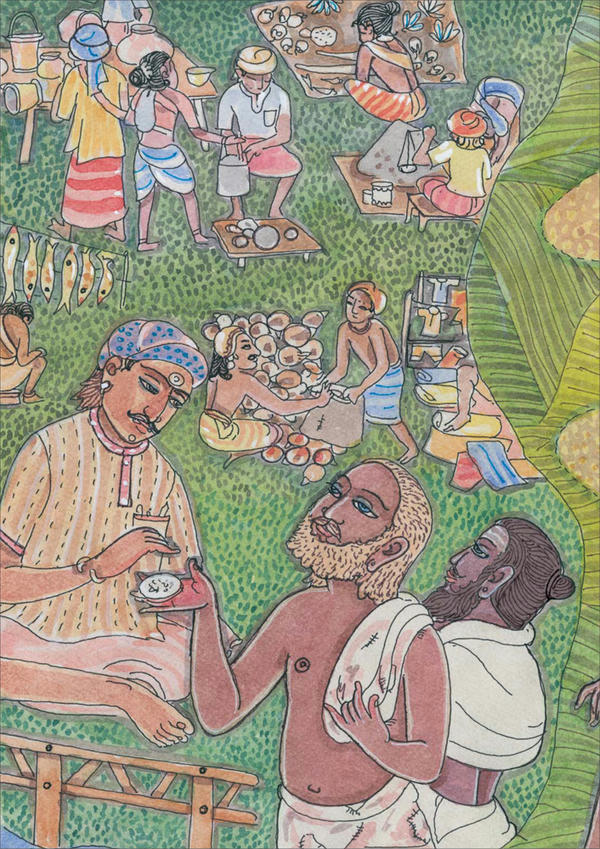

On many of their morning walks, Chellappaswami led the way straight to a village marketplace about fifteen kilometers from Jaffna to buy eggplants for lunch. The farmers in that region grow the finest eggplants in all the island and sell them in the open market. As soon as Yogaswami appeared in his compound, Chellappaswami would have a few cents tied in a corner of his sarong and be in a hurry to get there before the best eggplants were gone. It was a two-hour walk, even at Chellappaswami’s pace. Once there, Yogaswami would wait while his satguru went by turns to every stall in the market, soberly weighing the merits of dozens of eggplants before going back to finally buy one or two. Then they walked home to Nallur. §

He would march up to his hut carrying the eggplants in both hands and without a pause sit down to cook, lighting a fire on the ground to heat water in a clay crock supported by three rocks. Chellappaswami was a masterful chef, even though he simply boiled everything together in one pot—rice, spices and vegetables. As Chellappaswami ate mostly what he cooked himself, Yogaswami was invariably left sitting by, watching his guru prepare and serve him lunch. §

While the pot simmered, Chellappaswami would crush and add spices, then sit before the fire weaving palm leaves into bowls. He didn’t talk unless to rebuke Yogaswami if he felt his mind had wandered. This was their meal for the day, and it deserved his attention. But if Chellappaswami sensed the least desire or attachment toward the food, should his own mouth even begin to water, he would stop where he was and break the pot on the ground. No lunch that day. They went on to the next thing. §

Chellappaswami took care of himself, as bachelors must, and that included shopping and preparing his meals. Often he and Yogaswami would walk to the market, bargain for the freshest eggplants, then return to Nallur to prepare his famed Chellappa stew, in which all ingredients were cooked in a single clay pot.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •§

It was the guru’s way of disciplining his instinctive nature, keeping it reined in. He did this so often that the compound around his hut was littered with shards. Yogaswami later described his guru as “one surrounded by broken clay pots.” Chellappaswami did this even before Yogaswami’s time, smashing a steaming pot of food he had just prepared with the self-chastisement, “So, you want rice to eat!” Such was his renunciation. §

While the common man saw a common beggar in the sage, to Yogaswami, everything Chellappaswami did revealed his infinite grace. For him there was only one goal in life, Self Realization, and to allow anyone to think that less was sufficient was out of the question. In “The Lion,” Yogaswami captured his guru’s unabating message:§

Trekking to the seashore one day, Chellappaswami and Yogaswami came upon a lady selling eggplants, Yogaswami’s favored vegetable. Knowing his disciple’s penchant for brinjals, Chellappa turned and walked away, not allowing the desire to be fulfilled.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •§

Self must be realized by self. All must be pervaded by the Self. We must give up desire for wealth and woman, and shun the greed for ownership of land. We must guard dharma like our eyes. We must give worship to the lotus feet. All thought in us must die. O my great guru, thou mighty lion!§

Free from ignorance must we remain. We must behold God everywhere. We must have knowledge of the truth and ever cherish it. Falsehood and jealousy must be expelled. We must transform and into blessings change the things which cause delusion and make us confused. O peerless guru, whom others hold in high esteem! O lion, who in my bondage takes care of me! §

Perhaps it was precisely Chellappaswami’s stringent restriction on anything smacking of gratitude and adulation that gave wings to Yogaswami’s later poems, those odes to his guru that ring with the praise he felt but was forbidden to utter in Chellappaswami’s presence. In another song, “The Cure for Birth,” Swami extols Chellappaswami as the great soul who released him from the cycle of birth and death: §

Lord of the devas with sweet-scented wreaths adorned, bounty’s bosom, liberation’s flame, the all-pervading consciousness who with form and without form stands, who is both here and there, who king and guru has become, at sight of Him my heart was calm.§

My present birth he’ll terminate; in all my births with me he stayed; to make me free of future births, on me his grace he has bestowed. He is himself his only peer. Throughout eternity he stands. For those who offer praise to him, no future birth or death will rise.§

The Nallur Kandaswami temple is immensely popular throughout the peninsula, yet even today people may come there from distant villages perhaps only several times in their lives. Sometimes, without knowing why, such devotees would be called off the street by this eccentric rishi, then berated and abused for acts and thoughts they did not know were within them. §

Perhaps it went right over their heads, but he made them sit still while he acted out some dramatic conflict they had no notion had anything to do with them; they just listened politely and waited to leave. When he sent them away, they were perplexed by the experience, having at the time no idea of the purification they had undergone. Many did not even know the name of the man who put them through the ordeal. But later, sometimes after years, they would meet a situation in their life, an experience would come, and they would feel a release from what might have been. Some would remember and trace that release to the scolding they received from the sage of Nallur. Bringing flowers or fruit, they might come see him again to make their pranams. He would invariably chase them away, cursing them for daring to worship him. §

He was clever at avoiding or getting rid of people who wanted to drink the full measure of the guru’s grace but were not ready to live with his intensity. He would scold them and chase them off to start. If that failed, he would hide from them. Whenever his sister let into her compound a person he didn’t want to see, someone seeking to intercept him at his hut, he would stay away for days. §

Chellappaswami always got his way in these matters, one way or another. No amount of devotion or pleading or persistence prevailed. Just before Yogaswami came to him, a young fellow had drawn near whom Chellappaswami seemed to have taken a liking to. Villagers assumed the guru was training him as his disciple. He was allowed to stay around the teradi each day, but never at night. Even though the youth had no relatives in Jaffna and no place to go, Chellappaswami chased him away every evening, no matter how much he begged to stay. §

This went on for a few months until one day Chellappaswami told him to go live with a widowed merchant, a devotee who had opened a shop around the corner from the temple. He and his two children lived in a house behind the shop. There was plenty of room for the boy to sleep there, Chellappaswami said. It seemed a fine arrangement, but a few weeks later the aspirant approached him, standing in front of his hut one morning, and complained that there were just too many problems about living with the merchant. Would he please relent and let him stay with him instead? Chellappaswami inquired what the difficulties were. §

The boy explained that the man had a daughter who managed the household in her mother’s absence, and now people were talking about his living in the same house with her. That was the gossip going around, and it could have been avoided, he said, if he hadn’t been sent there in the first place. By this plea, he hoped Chellappaswami would feel sorry and admit he had made a mistake. But without a moment’s pause, the guru declared there was nothing to do now but marry the girl, and walked off to make the arrangements himself. A week later, the newlyweds were settled in their own home in Columbuthurai. Chellappaswami saw that everything went well for them thereafter, and they remained among his most faithful devotees. §

In Chellappaswami’s World

One morning during the hot season, Yogaswami was following his guru along a remote village path when Chellappaswami decided they should go to Keerimalai for a bath. There, as part of a complex of several temples near the ocean, one of which is a large Siva temple, are two walled-in, sunken tanks, fed by fresh-water springs, which people bathe in for purification. These pools are highly thought of, and people walk long distances to take the sacred bath. Adults and children joyously fling themselves into the crystal waters. Adults swim lengthwise and breadthwise. Children splash about and have their first swimming lessons here. §

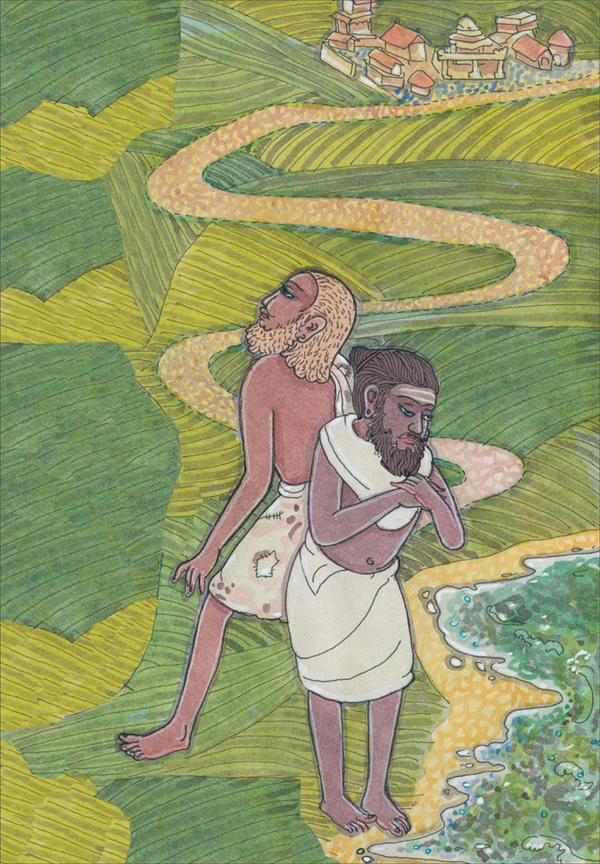

Off to Keerimalai they strode. Though it was an all-day walk to cover the twenty-one kilometers each way, which meant a late supper, Yogaswami couldn’t help looking forward to a cool dip in the ocean-side tank. Such luxuries came all too rarely in his guru’s company. Holding umbrellas aloft, they walked for hours in the parching heat. §

Finally, below them they spied the famed seaside tanks. Only a few pilgrims were there ahead of them. The sun at its zenith sparkled on the cool blue water, and a gentle breeze reached them from the ocean beyond. Yogaswami sighed and smiled, savoring the salty air. Chellappaswami looked to the left and right, then announced, “We have bathed,” and turned to go. A bit startled that he would not feel the cool waters, Yogaswami followed.§

On the way back to Nallur, they observed that the chariot festival was in progress at the Mauthadi Vinayagar temple. Chellapaswami stopped, saying, “You need refreshments.” He gave Yogaswami two cents to buy pittu. Yogaswami bought the sweet dish made of steamed rice flour and coconut and got some lime and jaggery water to go with it from the free refreshment tent. Chellappaswami, declining any food, stood by as his disciple enjoyed the snack. Just as Yogaswami finished the last morsels, Chellappaswami set out for home. §

Yogaswami walked briskly to keep up, as the food sloshed in his gurgling stomach. Thinking, “I can’t walk any more,” he paused. Without turning around, Chellappaswami shouted, “Oh, come, come.” It was not a comfortable walk. Back at the teradi in Nallur, Chellappaswami gave him a few cents for tea. Only then did he take anything himself. In one of his songs, Yogaswami alluded to such lessons about the body:§

Taking the body as reality, I am roaming like a fool. When the supreme and perfect one cured my delusion and made me his. That source of bliss—who graciously appeared, concealing the fair-tressed lady by His side—I saw at the city of Nallur, where naga blossoms fall like rain. When, through previous karma, my mind was in confusion and I was sorely distressed, God, of His great mercy, had the holy will to take me under his protection and come to Earth as the embodiment of grace. ’Twas Him I saw near the house of the chariot in the city of Nallur where the Goddess Lakshmi dwells. §

One day, first thing in the morning, Chellappaswami took Yogaswami begging. They would, he said, get something from a rich merchant who ran a store in the Grand Bazaar, the main shopping district in Jaffna. Arriving while it was still cool, they stood outside the shop, waiting for an offering. This merchant was actually a poor prospect, and Yogaswami knew that Chellappaswami knew it—a miserly fellow who never gave or put up with “worthless beggars,” as he called sadhus who approached him for alms. §

The merchant arrived an hour or so after they did and—while he surely saw the swamis standing there—went inside, greeted his clerks and sat down at a table on the veranda, in plain sight, as if he hadn’t noticed them. Business came and went as usual. He worked on his account books all morning, then closed the shop and went home for his bath and lunch. §

The two sadhus sat through the hottest hours. Chellappaswami was in blissful soliloquy. Yogaswami was pensive. The merchant came back in the afternoon and returned to work. Hour after hour, they stood by, waiting for alms. It was nearing time to close the shop for the day, and Yogaswami was growing impatient. Chellappaswami was quiet. Finally, the merchant closed his ledger and stood up to go. As he did, the eyes of the beggars caught his. He motioned to his clerk, and sent him out to give them one cent. One cent! Chellappaswami proudly held up the paltry coin as if it were a treasure, declaring, “Good wages for a day’s work!” Yogaswami wanted to speak his mind to the merchant, but Chellappaswami pulled him away, down the street and into a tea shop. He made him take the penny and buy himself a cup of tea. §

At first Yogaswami refused, struggling still with the storekeeper’s miserliness and not wanting to partake of any refreshment that his guru was not also enjoying. But Chellappaswami insisted. As Yogaswami drank the black tea, it suddenly struck him that Chellappaswami had begged all day only for his disciple’s benefit, thereby revealing his infinite patience. That man gave a penny along with his spite, and the guru took them both away. But Chellappaswami was ready to go, so he downed the last sip of tea and followed the guru happily back to Nallur. §

Yogaswami often told the story of the blisteringly hot summer day they walked the 21 kilometers from Nallur to the ocean at Keerimalai. Just as Yogaswami was ready to enjoy the cool waters, his guru turned, declared, “We have bathed,” and marched back, teaching his disciple a lesson in detachment.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •§

What passed between them was theirs alone. Chellappaswami rarely spoke straight to his disciple; his method was indirect, yet Yogaswami understood him perfectly. He didn’t ask questions about the spiritual path, about Siva, about the Saiva Siddhanta philosophy, about anything, but simply remained open to all that Chellappaswami offered. §

There was never a question of whether Chellappaswami would give. He gave and gave and gave to all who could possibly receive. All his life Yogaswami exclaimed in wonder that in the very first look he received from Chellappaswami, all the effects due from his past actions, all his desires and all his attachments to the world, were erased. This and more he eloquently expressed in “Hail to the Feet of the Satguru,” enumerating the treasures that Chellappaswami bestowed upon him:§

Hail to the feet of the teacher, who gave initiation and made me his, saying, “You are not the body; you are the atma!” Hail to the feet of the able master, acclaimed as the great tapasvin, who gave the sweet and noble saying, “Be and see!” Hail to the feet of the satguru who came and guarded me like a mother so that I need not frequent the homes of the miserly and mean! Hail to the feet of the true guru who came like a madman and took in his hands my wealth, my body and my life—all three! Hail to the holy dancing feet that have become what is within and without, body and life, you and I! Hail, ever hail, to the anklet-circled feet of the revered and bounteous one who bestowed on me the priceless blessing of living as I please! §

Hail to the feet of the satguru who placed his feet upon my head, that I might not be bewitched by the beauty of ladies bedecked with blossoming flowers! Hail to the feet of the perfect one who gave me the grace to prosper, by looking at me, his slave, and saying, “Why do you have doubt?” Hail to the sacred feet of the great giver who dispelled my fears and made me his and, by one word, caused me to be as a painted picture! Hail to the holy feet of the good tapasvin who revealed the whole world within the one word Aum and told me, “It is I.” Hail to the feet of the precious one who at the proper time took me as his own and showed to me the glorious dance at beautiful Nallur! Hail, all hail, to the feet of the gracious master who, by his laugh, saved me from wandering here and there in search of food and money! §

Yogaswami witnessed many times the power of the guru to expiate the effects of deeds and magnify the spiritual qualities in the disciple. Yet, he observed that precious few people ever suspected what Chellappaswami had done for them. The magic of the guru occurred daily around Chellappaswami, but always without his taking on the outward persona of guru. Only to Yogaswami and Katiraveluswami, and perhaps a few others, did the sage of Nallur show anything of his deepest self. Often, when his two disciples were with him, he would dance around laughing and tease them, “No, you haven’t caught me yet! No, you’ve not caught me yet!” §

On occasion Chellappaswami would go into a shop in Jaffna town and demand certain things—a few cents, a coconut or some bananas—always persevering until he got what he wanted. Once, when Chellappaswami was making such an ultimatum, a devotee was standing nearby. The shopkeeper was shouting back at the guru, refusing to give and ordering him to get out. Chellappaswami continued with accelerating insistence. Embarrassed by the exchange, the devotee offered to purchase whatever the guru wanted, anything in the shop. But the moment he spoke up Chellappaswami turned on him, chased him out of the shop, returned to the owner and barked, “I am doing a service for you, and for that I require payment.” §

One festival day Yogaswami stood on the Nallur path, awash in eternal bliss due to the contentment that everything was in his hands. The Deity was being taken in procession round the temple amid an enormous crowd of a hundred thousand or more. Yogaswami said, “They are not taking umbrellas. Today the Swami (the Deity) being taken in procession is going to get drenched thoroughly.” §

Almost before Yogaswami completed the sentence, his guru roared from the distance, “Many are the people who have said such things on this Nallur road.” It was a not-so-subtle correction from his guru—and in a dismissive voice. Yogaswami was humbled. When the clear blue sky turned cloudy, and rain began to pour minutes later, Yogaswami was openly embarrassed to see his petty prediction come true. Then and there Chellappaswami had uprooted the shoot of miracle-mongering that had begun to sprout in the disciple. §

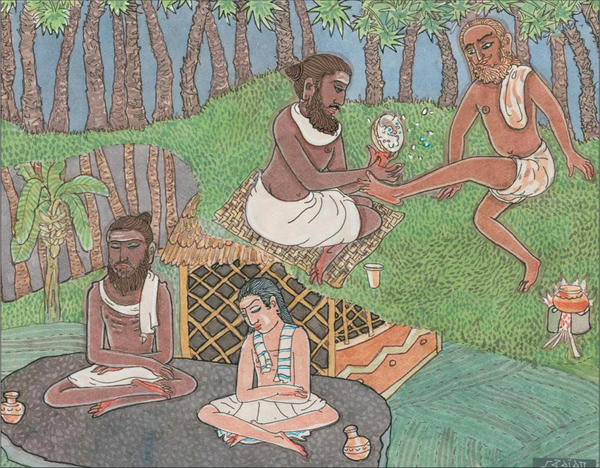

To prepare Yogaswami for his initiation, Chellappaswami required him, along with a second disciple, to sit on a large stone slab. For 40 days the pair meditated and fasted. To end the fast, the guru prepared a meal, handed a bowl to each and then kicked the bowls from their hands, declaring, “That is all I have for you!”

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •§

“I Beheld the Sivaguru”

By the fall of 1906, Yogaswami’s inner search had reached full stride. For several years he had been with his guru. The young man who once walked forth and back from Kilinochchi to Nallur was now gone. In his place stood a veteran swami, robust and barrel-chested, in threadbare white cotton veshti, his thick, grey-flecked hair wound into a knot at the back, his forehead glowing with vibhuti, his stride powerful and purposeful. §

A thick, black beard framed his high cheeks and soft brown eyes. Their steely calm gave a glimpse of the man—tempered by obedience and alert to vast depths of silence within. Those who looked into his eyes seemed to see the cosmos itself, so deep and serene. Yogaswami was like a young lion. His eyes were as sharp as steel. His 34-year-old body was lean and fit. Having found the treasure of treasures, his guru, he was more eager than ever to pursue the demanding inner path ahead. §

Yogaswami undertook a rigorous routine of sadhana and tapas under the guidance of his satguru. One tapas he performed was to rub chili paste on his body and meditate bare-chested in the midday sun—and the sun in Jaffna is intense—or prostrate and roll around the temple in the scorching hot sand, as devout penitents still do today. Vaithialingam reported that Yogaswami rolled his body in this way the full three kilometers from Columbuthurai to Nallur two or three times.§

Between Columbuthurai and Nallur there is a charming Ganesha temple, the Kailasa Pillaiyar Koyil, where guru and shishya would meet and sit for hours. The odd couple also visited the Panrithalaichi Amman Temple, where they would cook pongal, a sweet rice dish, make their offerings to Amman, pray and meditate, then enjoy the pongal as their lunch before returning by foot to Nallur Temple. This was their pattern until early 1910. Ultimately, they no longer moved as guru and disciple, but as one being. Chellappaswami’s harshness had waned. He was still stern, and few of his ample eccentricities ever left him, but as he neared his seventh decade he softened and no longer pushed Yogaswami away. Swami shares glimpses into these momentous days in “Darshan of the Master:” §

In Nallur’s noble town, where dwell great sages who no second thing perceive, I beheld the Sivaguru, Chellappan by name, whose state is such that he cannot be enmeshed in the lustful net of women’s sparkling eyes. “All is well, my son,” he lovingly declared.§

From time’s beginning until now, all men have made inquiry as to whether it is one or two or three. He who beyond the reach of all philosophy remains came as the glorious guru of Nallur and upon me high dignity bestowed.§

The taintless one, who air, fire, water and the mighty earth became, whom none can comprehend, as the satguru came there face to face, and, having banished all my doubts, took me beneath his sway. Then indeed I gained the state whereof the gunas I was free.§

In the golden land of Lanka, where birds start at the sound of falling water, in Nallur’s town, where the son of Him who holds the fire is pleased to dwell as the divine guru, to bestow true life upon me, he appeared and showed to me his feet and made of me his man.§

Change was in the air. Yogaswami sensed it, and saw it in Chellappaswami’s sometimes searching glance, less stern than expectant, which said more clearly than words what was to come next.§

“That Is All I Have for You”

Chellappaswami’s second disciple, Katiraveluswami, was around through these years. Yogaswami saw him infrequently. Brothers though they were, forged in one fire, they were rarely seen in the same place, and knew little more than each other’s names. Still, in one another they saw themselves. When they met they would know and nod. Chellappaswami seemingly went to any length to keep them apart, out of sight and away from people. §

During the week of Skanda Shashthi, Chellappaswami called his two shishyas together and led them to a quiet place “to meditate.” Under a shady ironwood tree, within shouting distance of Nallur Temple, was a long slab of flat, chiselled granite, abandoned there years before. Chellappaswami seated them and ordered them to go inside until he called them out. They sat on the bare stone and closed their eyes. Nallur’s sage quietly walked away. §

Later in the day he brought them each a pot of water. It was several days before he came again, bringing tea, leaving it beside them without a word. He came and went in this way for several weeks, guarding and watching, careful not to disturb their vigil. He assigned a senior devotee to watch after the two tapasvins as well. They grew thin from the fasting, haggard and sunburned, but neither moved from his seat, except for nature’s call. After a month, they received only water. §

Chellappaswami would come and stand by for hours at a time, looking from one to the other. Finally, on the fortieth day (some say it was less than forty days), the guru approached, solemnly brewed tea on the open fire and filled their metal cups. As they feebly raised them to drink, he abruptly swung out, knocking the cups from their hands. They watched unperturbed as the tea spilled onto the dry sand, startled but accepting of the guru’s gesture. §

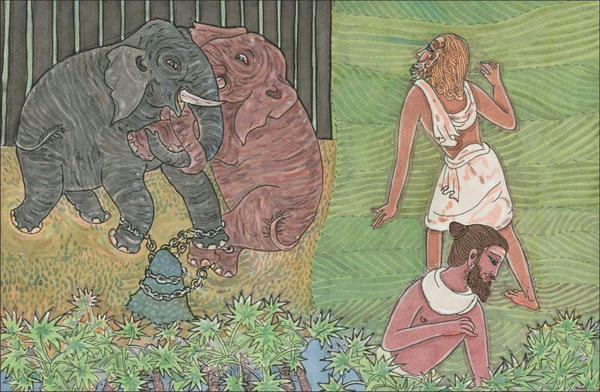

He glared at them briefly, then began cooking a meal. The two watched with interest—it was a scene they had witnessed many times. He wove eating bowls from palm leaves while the pot of rice and curry boiled, an inimitable concoction some called Chellappa Stew. When the food was ready, he ladled out small portions and handed a steaming bowl to each. As they began to eat, he kicked the food from their hands, shouting, “That is all I have for you! Go and beg for your food.” Though it shook them both to the core, they knew this was a rare spiritual initiation, a sign that their training was complete. “Two elephants cannot be tied to one post,” he announced, releasing them from their austere vigil. §

Following the initiation of his two disciples, Chellappaswami sent them off in different directions, declaring that you can’t tie two elephants to the same post.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •§

Not many days passed before Katiraveluswami disappeared. It is said he went to India. Yogaswami also went missing. He had returned to Columbuthurai to rest and recover from his arduous fast. After one week, he walked to Nallur to be with Chellappaswami. Blissful and eager to see his guru, Swami entered the compound. §

During the few minutes they sat together, Chellappaswami blessed him with the following words, “Look here! Look here! The city of Lanka I have given, I have given. The king’s crown I have given, I have given, as long as the world exists, as long as the seas exist.” This final diksha took place on the second Monday of the Tamil month of Panguni (March-April) in the year 1910. It was witnessed by Thiagar Ponniah, a devotee of Chellappaswami and neighbor of Yogaswami. Ever thereafter, Swami observed that day as his diksha day, which he described as a coronation, like being crowned a king. §