Chapter Twelve

Yogaswami, the Young Guru

By this time many people had taken note of Yogaswami, but a rare few knew of the spiritual power he carried. Chellappaswami did not make it known that he had ordained Yogaswami. He made nothing of it, thus allowing Swami the luxury of obscurity so he might unfold the power of that initiation within himself. But this secret, like so many, was hard to hide. Inthumathy Amma shares:§

In those early days there were still a few devotees who traveled from Columbuthurai to worship Chellappaswami. They knew through distinct signs that Chellappaswami had given all his wealth and blessings to Siva Yogar. Hence, even though they treated Siva Yogar as a colleague, they had great, deep-rooted devotion for him within their hearts. Like the great devotion they had for Chellappar, their great devotion to Siva Yogar was concealed in their hearts, and outwardly they behaved like friends. Among them there was one devotee, Thuraiappah by name, who could not conceal his eagerness. He was accustomed to singing Devarams in the Nallur Temple and at the steps of the chariot house. He began to come to the hut and sing Devaram hymns in Siva Yogar’s presence. This was the first significant act in those early days to show that the hut was the temple of a living God. §

Ratna Ma Navaratnam describes Swami’s life during this period:§

From 1915 onwards, Swami led the life of a renounced recluse; he would be seen frequenting the illupai tree at the school junction in Columbuthurai, the Nallur teradi, the Ariyalai hermitage, the Thundi Crematorium, the Esplanade and the byways of Grand Bazaar. These were the years of gestation and samadhi experiences.§

According to T. Sivayogapathy, son of A. Thillyampalam, Yogaswami met frequently with his strong devotees, such as M.S. Elayathamby, A. Ambalavanar, Mudaliyar S. Thiruchittampalam, M. Sabaratnasingi, V. Muthukumaru, Kalaipulavar K. Navaratnam, T.N. Suppiah, C. Mylvaganam and Pulavar A. Periyathambipillai, having discussions under the illupai tree or in his nearby hut. This began in 1916.§

Following his satguru’s mahasamadhi, Yogaswami led a quiet life of sadhana and samadhi, years when he was seen but not known.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • §

Jaffna had a long history of philosophical and devotional accomplishment, and those in the community who were both seekers and immersed in spiritual literature gravitated to Yogaswami, who was well versed in monistic Saiva Siddhanta. They found him a rare alloy of knowledge and realization, and were inspired that he encouraged their intellectual and teaching pursuits. Among them was a lawyer, Tiruvilangam, from Jaffna, an authority in Saiva Siddhanta who met Yogaswami in 1920. He authored several books related to Sivajnanasiddiyar, Sivaprakasam, Tiruppugal and Kandar Alankaram. At the time he passed away in Colombo, Yogaswami ran out of his ashram and looked towards the sky and shouted, “Tiruvilangam is now mixed with Sivasothy! (‘Light of Siva’).” §

Another, Sri T. Kumaraswami Pulavar of Kokuvil, specialized in Saiva philosophy, giving lectures and satsangs in temples and later authoring a few books under Yogaswami’s direction. Sri Somasunthera Pulavar of Navaly, an authority in Hinduism and Tamil literature, similarly served the Saiva cause. §

Yogaswami loved the beauty and profundity of Tamil literature and through these men was able to bring a small renaissance to the Jaffna people. His own poems drew deeply on the ancient scriptures, while adding an illuminating directness that to this day commands the deepest respect among Tamil literati.§

Life at the Columbuthurai Ashram

One devotee fondly recalls Swami’s early days in his hermitage: §

Even after devotees began coming in great numbers, Swami would become rapt in meditation at will, as though they weren’t even there. On Sivaratri it was his custom to meditate through the night. A few devotees who had the good fortune to be with Swami at these times saw a light shine where Swami’s body should have been. They believed that this was the divine light of his true, blemishless form. Even those who could not see this shining light were amazed to behold the erect, still form of Swami, seated like a statue. His golden form was as still as his umbrella in the corner. On one occasion when Swami sat so motionless during meditation, a crow came flying in, rested on his head for awhile and flew away. §

That hut was an unimposing dwelling with mud walls, thatched roof and a clay floor covered with cow dung, all set in a sandy compound. Inside the single room, a low wall partitioned off a quarter of the space to the right. Here Swami kept his meager possessions and food supplies. On the south side of the room, to the right as one entered, was a wooden plank on which Swami slept, meditated and also sat to receive visitors—a five-centimeter-thick plank of neem (Azadirachta indica, a species famed for repelling insects) that had small feet to keep it fifteen centimeters off the floor, away from crawling critters. §

For a few years, there was a snake pit in the corner of the room where he slept, and others in the compound, not an uncommon thing in that arid region. In those days, Yogaswami slept on the dung floor in the small partitioned-off space. One night he awoke to find a snake by his side. Confronted with the deadly serpent, he made swift assurances, “It seems that you had best sleep here by yourself. I will go and occupy the other side.” From that day onward, he slept in the main area of the room.§

For some time Swami did not allow anyone to light a lamp inside the hut, though camphor was permitted to bring dim respite from the dark. And he never allowed anyone to modernize his hermitage, preferring its austere style, though every other year he allowed a few close devotees to re-thatch the roof, which they did within a day’s time. He would be driven by car to one of his favorite places while they took off the old thatch and replaced it with fresh materials, then cleaned the entire interior and put all of Swami’s things neatly back into place. By 6pm, when he returned, the work was done. In the early twenties he consented to cementing the floor of the hut due to the increasing number of snakes coming up through the floor. §

The illupai tree was 40 meters east of his hut, on the other side of a small lane named Swamiyar Road. The north side of the hut bordered Main Road, on the other side of which stood Columbuthurai Maha Vidyalayam (school) and a Pillaiyar temple. §

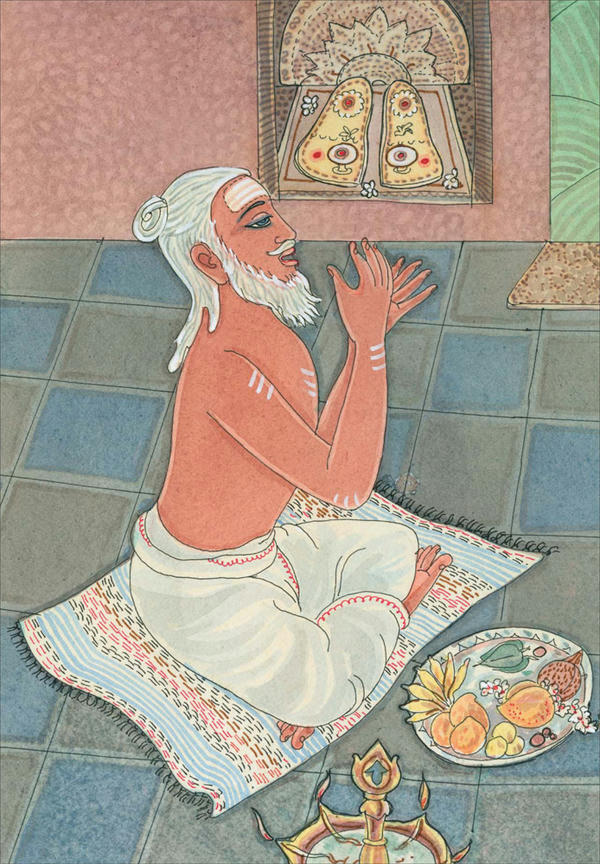

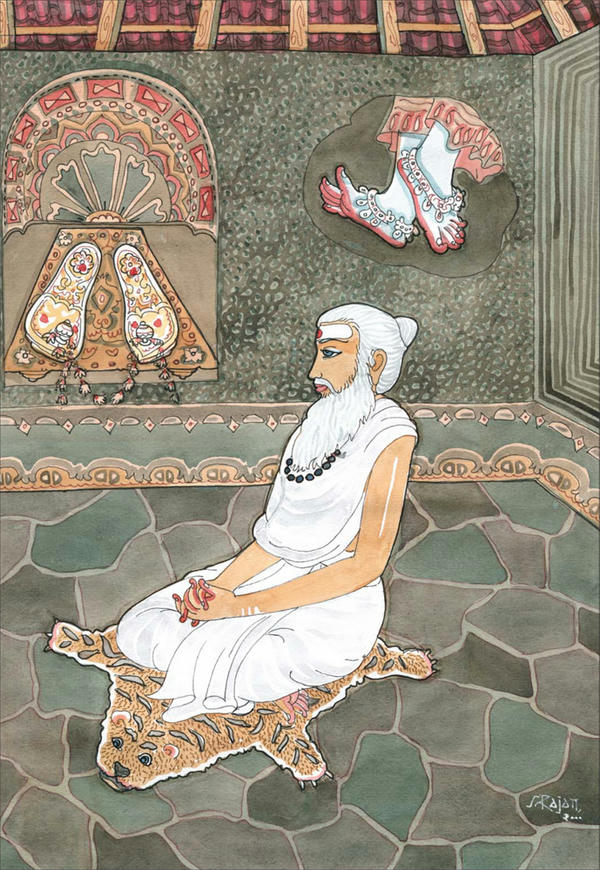

In an alcove in the boundary wall of the temple’s garden, Yogaswami kept and worshiped the divine sandals of Chellappaswami. Later he installed his guru’s tiruvadi inside the hut, in the northwest corner of the room, on a pedestal that also supported a small standing oil lamp which he kept constantly lit. Each morning after his bath at the well, he adorned the sandals with flowers and silently offered burning camphor to his satguru, the sage who taught him to see all as it is–as himself. §

In front of his wooden seat and bed, on which he sat facing north to give darshan, he always kept certain items on the floor in front of him: a small camphor burner and a few camphor tablets, a brass pot of fresh water, which only he used, and a stainless steel tumbler for drinking, which served as a cover for the pot when not in use. Flowers from devotees were also placed on this spot. §

Inthumathy Amma describes life at the ashram: §

From 1914 until Yogaswami’s mahasamadhi in 1964, the little hermitage in Columbuthurai served as his abode and ashram. Devotees would gather daily to be with the guru, sing, receive his guidance on the path and enjoy his upadeshas and radiant spiritual presence.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •§

In the blessed hut where Yogaswami sat, the Saiva personage M. Tiruvilangam, who was well versed in the Shastras and followed the precepts of Saivism, and other dignitaries, came and sat in silence. Sir Ponnambalam Ramanathan and other political leaders waited patiently in the compound of the ashram for the opening of the doors, with trembling and shivering hearts. Kalaipulavar Navaratnam and other educators began to move ’round Yogaswami. Tamil literary stalwarts, like Somasunthera Pulavar and Ganeshaiyar, stood with bowed heads in Swami’s presence. Many who lived in Jaffna at that time, those who had studied thoroughly, ladies who were illiterate and who worked in the fields, those who drove bullock carts, in short all and sundry began to flock ’round Swami.§

Even atheists and those who could not give up their alcohol and cigarettes prostrated before him. Christians, Buddhists and those of the Islamic faith sought him. From early morning till midnight a stream of devotees came and went from that heavenly hut. From dawn to dusk one could see cars, bullock carts, hand carts all parked in a row on the road in front of the ashram.§

The only sounds in the early days were Thuraiappah’s Devaram at dawn and dusk. At that time Mrs. Arunachalam, having completed a pilgrimage by foot to Kataragama, started the practice of lighting a lamp. Another devotee gathered the courage to light camphor and worship. The sweet sounds of Devaram and kirtanas [songs] began to resound from the ashram. The delightful aroma of the objects of worship permeated the air.§

Swami spoke to those before him so naturally. But even in those simple words high philosophy echoed. Once Swami asked a devotee, “What news?” The devotee replied normally, relating some recent incident in the community. Swami retorted, “There is no news. Everything is as it should be.” §

At times, according to the needs of the devotees before him, sections from the Vivekachudamani, Bhagavad Gita and other philosophical works would be read. In order to give the true meaning of these readings, Swami would interrupt and comment on them, thus opening the eyes of the devotees. The Sivapuranam was chanted every evening. Devotees assembled in great numbers for the privilege of chanting in his presence, as he was seated there like Lord Siva, the object of the Sivapuranam. §

When the chanting was over, Swami gave prasadam to the devotees who were ready to go, saying, “Go and come again. But we do not go and we do not come.” While walking away on the road, the devotees chattered appreciatively with pride, “He is pure soul who has no going or coming.” Thus, in this way that ashram became a temple where a living God stayed.§

Yogaswami often took refuge in Jaffna’s Vannarpannai Siva Temple. He would sit in front of the quiet shrine of the Goddess as Thaiyalnayaki and there compose his mystic songs. He told devotees that one day while meditating there he heard Her anklet bells as She danced in the world of light. Thaiyalnayaki literally means “beautiful Goddess.”

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • §

T. Sivayogapathy shared:§

Thuraiappah used to visit Yogaswami’s Ashramam daily at 6:30 pm and sing the Parrot (“Killiye”) Natchintanai. Thuraiappah’s residence was situated just 100 yards from Swami’s hut. On many early mornings they walked to the Columbuthurai beach for a stroll. My beloved father told me that Thirugnanasampanthar, Thuraiappah and Yogaswami went to Panrithalaichi Amman Temple every first Monday of the Tamil calendar month to offer pongal at the temple, worship and enjoy pongal as their lunch before returning to Columbuthurai Ashramam in the evening. They made the trip by bullock cart.§

Gradually the hut became a regular place of pilgrimage for devotees from near and far. V. Muthucumaraswami, in Tamil Sages and Seers of Ceylon, tells what it was like to visit Swami’s kutir:§

In my late teens I remember visiting Yogaswami at his hut at Columbuthurai. There was the smell of incense and camphor. There were flowers of various hues, the shoe flower, the jasmine, the mullai, the red lotus, the champaka and more. There was a deer skin on which sat Yogaswami. The scene reminded one of Sage Vishvamitra or Sage Vasishtha, mentioned in the Ramayana. Yogaswami had a flowing beard, and his hair was silver. His eyes were magnetic. People came with various offerings: betel, areca nut, mangoes, pomegranates, pineapples, rice and vegetables. Some came with prepared food: pittu, stringhoppers, dosai, vadai, modakam, etc. Yogaswami would ask the people to be seated quietly, and a few devotees would distribute the offerings to the rest.§

Mr. Tamber, principal of Central College, paints a picture in S. Ampikaipaakan’s biography of Yogaswami: §

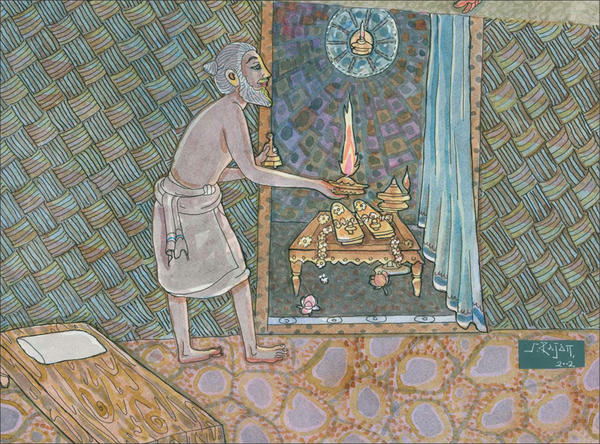

Yogaswami’s hermitage had the simple austerity of a monk’s quarters. In the main room there was a neem-wood platform that was his bed at night and his seat during the day. Behind a curtain he kept the sandals of his guru, which he worshiped each day with camphor.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • §

Darkness was setting in when we reached the junction of Columbuthurai and Swamiyar streets and we saw a divine being sitting under the shadow of the street kerosene lamp. He was wearing white veshti and sitting in padmasana. Swamigal was indeed magnificent looking, like one of those ancient rishis, with his lion look, his smooth skin, white beard and grey hair. When he emerged from his meditative state, his eyes were shining as a tiger’s eyes reflect in the night. Then he started singing devotional songs as if a dam had opened into the ocean. For two hours it was like a hurricane blowing. Those songs came deep inside from his lungs. We and others were enchanted, and all stood mesmerized by his music. There was absolute silence and peace when he finished singing. §

At the Marketplace Temple

In the early 20s, Yogaswami took to spending time in front of the Siva temple in Jaffna’s Vannarpannai district, the same temple Kadaitswami had frequented. Boons and blessings flow so abundantly here, in the midst of Grand Bazaar, that the temple became the richest in all of Ceylon, overflowing with devotees’ gifts of land, jewels and gold. Jaffna’s goldsmith shops surround the site, bolstering the temple’s staggering shakti. India and Ceylon worked almost as one nation in those days, and cartloads of flowers arrived daily, offered by devotees of this temple living in India. §

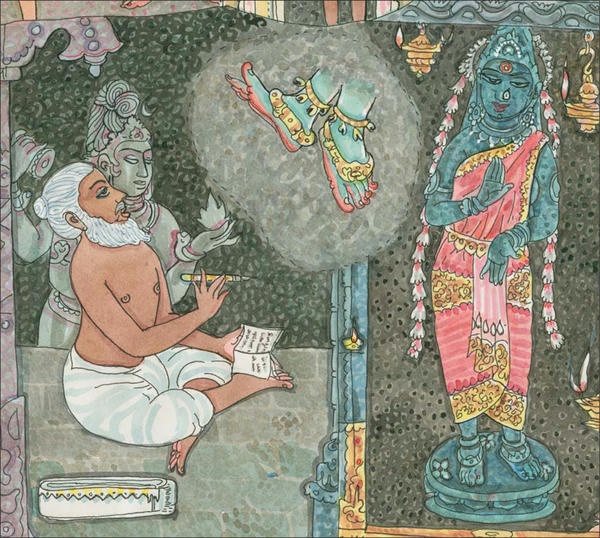

Here Swami dissolved himself in the darshan of Thaiyalnayaki, Mother of the Universe, the Shakti of Siva. Her shrine was not far from Siva’s, but more secluded, the sannidhya much softer, offering a protectiveness he loved. He found this quiet, unlit corner of the temple a special refuge where he could meditate, compose spiritual hymns and commune mystically with Chellappaswami. §

In his reveries he said, “All one needs is to hear the jingle of Thaiyalnayaki’s anklets as she walks around the temple.” He himself heard Her anklets jingling and shared the following verse with devotees:§

O Mother Thaiyalnayaki!

This is an opportune moment, Mother!

World famous is the great city of Vannai

That You have come to, Vani! Sivakami!

Of whom Kandaswami was born

O Mother Thaiyalnayaki!

O Mother Thaiyalnayaki!§

Though the temple was crowded with devotees, no one disturbed him. Worshipers revered his presence. Still, to one devotee, there was too much hustle and bustle for the inner work he sensed Yogaswami was engaged in. S.R. Kandiah watched and waited over a period of weeks, then approached Swami while he was walking about after a long meditation. “Vanakkam, Swamigal. Please forgive my boldness, but I have a storefront a short walk from here. It would be a great blessing to me if you would use it as your shelter.” §

Yogaswami accepted and was seen there often. He began teaching a little, too. Sitting on a simple wooden bench, he told passersby that the Mother’s love is so powerful that it can dissolve you fully if you can hold yourself within it. Yogaswami was often seen around the nearby temple, worshiping Siva and Thaiyalnayaki Amman.§

The Council of Rogues

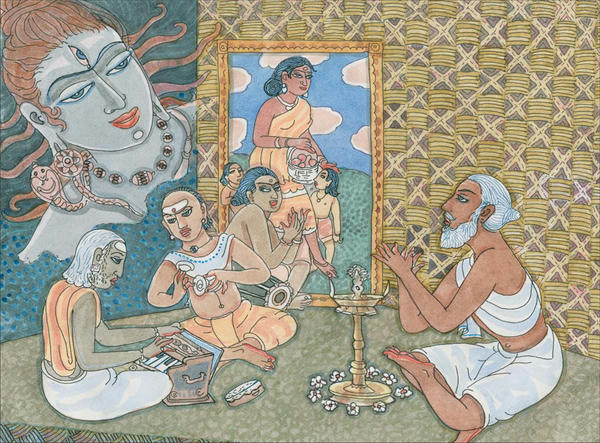

In the 1920s and 30s several professional men drew near, whom Swami endearingly called “The Most Distinguished and Learned Council of Rogues.” He met with this devout and educated group—teachers, lawyers, doctors and businessmen—roughly once a week at one of the members’ large homes, built at the same time and in the same neighborhood as the Vannarpannai Sivan Temple. They were the core group of the future Sivathondan Nilayam.§

Swami was at ease with his Council of Rogues. In their company he could relax, and so could they. Often they took turns reading from Hindu scriptures. As they read, Yogaswami would stop them at crucial points to make comments. They valued these moments beyond measure. But he would not let them hold him or the saint whose words they read above themselves. “You must become the speaker of the words you read and hear. You are not who you think you are. You are the One. That is what you must practice.” §

Yogaswami sometimes spoke of Swami Vivekananda at these gatherings. He described the young swami, whose lectures he had attended in January 1897, as like a lion roaring, pacing up and down the platform, barely able to express all his perceptions and direct all the energies coming through him. At the outset of his talk, the 34-year-old Vedanta monk lamented, “The time is short, and the subject is vast.” Swami reiterated that saying throughout his life. §

This august assembly included Sir Vaithilingam Duraiswamy, Dr. C. Gurusamy, Mr. A. Thillyampalam, Mr. V. Karalasingam, Dr. V.T. Pasupathy, Pundit T. Mylvaganam (later Swami Vipulananda), Kalaipulavar K. Navaratnam, Mr. C. Mylvaganam, Mr. V. Muthukumaru, Mr. V.S.S. Kumaraswamy, Mr. T.N. Suppiah, Pulavar A. Periyathambipillai, Mr. R.N. Sivapragasam, Mr. M.S. Elayathamby, Mr. M. Sabaratnasingi, Mr. Tiruvilangam, Supreme Court judge H.W. Thambiah, Mr. M. Srikhantha, Mr. Kasipillai Navaratnam, Mr. T. Sinnathamby, Mr. K.K. Natarajan, Pundit A.V. Mylvaganam, and Justice of the Peace S. Subramaniam. Most remained Swami’s devotees throughout their life.§

Perambulations

Throughout his life, Swami talked openly with Chellappaswami as if he were there physically. Only in the later years did devotees learn that Swami had matured the siddhi of communicating with Chellappaswami in the period following his mahasamadhi. From then on, Chellappaswami guided him inwardly. Swami explained that this was also when he established connections with the transcendental forces of the universe, with the Gods, the devas and the Saivite saints. §

As a young guru, Swami was often away from Jaffna for long periods. He would go to Colombo, or to the up-country, or possibly to a retreat place he had in the village of Poonagari, forty kilometers from Columbuthurai, out in the middle of rice paddies where there is a Ganesha temple and beside it a pool full of lotus flowers. On the other side of the temple stands a shady kuruntha tree, the tree sacred and revered by Saivites because under such a tree Saint Manikkavasagar saw Lord Siva as his guru. No one knew of this place, so Swami was not disturbed there and would stay for days at a time. It was peaceful, amid farmlands, with tireless farm workers all around.§

Swami loved to walk and would cover great distances throughout the Jaffna peninsula. In later years, when droves of devotees began arriving at his gate, he would rise early before anyone appeared, grab his umbrella and take to the unpaved roads, walking for hours without respite, visiting the sacred spots en route and often stopping for lunch at a devotee’s home unannounced, only returning to his hut when he knew no one was there, or only the most devout. §

He was familiar with every street, every lane, every path. One day, in the 1940s or 50s, there was a terrible storm in Jaffna. High winds drove intense rain for several days without ceasing. Trees were blown down and roads flooded. After the storm, Swami asked one of his close devotees to drive him around in order to survey the damage. Whenever they came to a place where the road was impassable, Swami would navigate another route, down narrow lanes that only locals knew. When the devotee expressed his astonishment at his geographical acumen, Swami exclaimed, “This is my estate. I have walked every inch of it.” No matter where he went, no matter how long he was gone, Yogaswami always ended up back under the illupai tree. §

Swami was a stout man, five feet seven inches tall, an average height for Jaffna men in those days. Robust and strong, he could walk sixty kilometers in a day as a matter of routine, even into his seventies. And he was not averse to using his ominous presence and physical prowess to intimidate people he wanted to keep away. One devotee, Dr. S. Ramanathan, shares an unforgettable encounter: §

I went to visit Swami in 1920 with Advocate Somasunderam of Nallur. As a youngster, I was proficient in sword fighting and similar arts. As a result of these skills, I was a little arrogant. On my way to the ashram, Swami came to the middle of the road and felled me. I will never forget the incident. Even teachers of the martial arts cannot show that level of proficiency with their hands and legs. The only skill that gave me pride caused me to fall flat on the earth that day. Swami then took me to the ashram and showered me with love and affection. It was only in later years that I understood the divine sport that made me eat the dust on that road. Thereafter, whenever I traveled to Jaffna I went to the ashram and obtained his darshan. Sometimes he would scold and chase me away. Whenever I went with the sole purpose of seeing him, he would greet me and show great affection. §

Most people kept their distance. If they saw Swami coming down the street, they hid or went the other way. People took long detours to avoid passing the illupai tree. Sometimes, though, a curious, unwary person would venture close. Yogaswami would scold in a booming voice. If that did not drive the intruder away, Swami would strike him to make sure his curiosity would not get the better of him again. Decades later, Satguru Sivaya Subramuniyaswami gave his insight on such outbursts of ire: §

They say that Yogaswami used to get angry at people. People couldn’t stand his wrath, but afterwards they would say that they had been blessed by it. How does this differ from the ordinary person’s fiery anger of blacks and reds with fire shooting out uncontrolled and uncontrollable? Yogaswami would send out white flames, lavender flames in his righteous indignation. For the devotee’s own good he would say, “I am going to cut out all of this terrible stuff within you.” He would have the appearance that he had lost control of anger, but it would not be the anger of the instinctive person. Rishis, they say, get very dominant and very angry. They use the word anger, but it would be more accurate to call it righteous indignation, a white flame. Then people feel that they are blessed, because afterwards they are totally free of what was bothering them before. It had been totally burnt out of them as a blessing. §

In those days, his hut in Columbuthurai was far more remote and inaccessible than in later years. The road between Jaffna town and Swami’s village was just a wide trail through overgrown bushes, and there were no houses for three or four kilometers. People feared robbers when they came that way at night, so Swami was spared the faint of heart. Only ardent, fearless devotees dared the journey from Jaffna in the evenings. §

One night a few boys came. They had tried to catch Swami as he walked around Jaffna but could not keep up with his swift stride. By the time they arrived, Yogaswami was lighting oil lamps for the evening. Ignoring them, he sang the sacred songs he recited each evening. Then he invited them into his hut and asked why they had come. They explained that they had recently taken their graduation exam. If they passed, they would be able to go on to the university, maybe abroad. §

The results had not been published, and they were worried. They had also begun feeling the weight of responsibilities they would soon assume as adults, and sensed that this night might be the proper time to make a pilgrimage to the sage of Columbuthurai and seek his advice. They knew of the power of blessings that could come from such a soul. Quickly Swami put the question of the exam results out of their minds. “You are bright boys and good students. Why do you worry? You must never base your actions on fear.” §

Swami knew they were at a point when they could stray from dharma, as so many do at this age. But with proper direction they could develop a deeper understanding of their life’s purpose. He spoke forth strong direction for their lives, urging them to continue to obey their parents, to remain chaste and not be taken in by any of the fanciness of the world. He described the ideal perspective to hold throughout life: §

There is no one above us or superior to us. Good and evil cannot touch us. For us there is no beginning or end. We don’t like or dislike. We don’t desire material things. The play of the mind doesn’t trouble us. Nor are we limited by place or time or karma. We simply watch that which goes on around us.§

Rajayogi Prostrates

There lived a brahmin named Sankarasuppaiyar, respectfully known as Rajayogi. Born in Jaffna, as a young man he had left home for South India on a spiritual quest. For years he performed sadhana and received training in philosophy and public speaking. He matured as a brilliant, highly respected orator on Saiva Siddhanta. At Hindu temples on special days after the pujas, speakers and musicians perform in the courtyard. Rajayogi would speak at such occasions throughout South India, elucidating the fine points of Saivism, telling stories and explaining their meaning. People came from all over to hear his oration. In a dramatic, yet simple style, he made the inner significance of Saivite worship available to those who had been following the rituals without much understanding. §

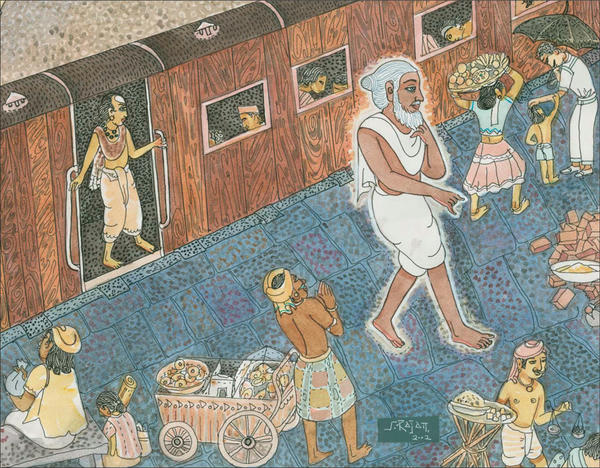

Sometime in the early 1920s, the prodigal son returned to Jaffna, where he was widely known and highly regarded, even though he had not been home for years. Many Sri Lankans pilgrimaging through South India had heard him speak at the ancient stone temples. At last, he was returning, a hero of sorts, to give a series of religious lectures. Rajayogi landed by boat in Colombo, spent several weeks enthralling audiences in the capital, then set out for Jaffna by train. §

The whole community was excited. Such events rarely occurred in the quiet North. Representatives of the reception committee took the eight-hour train ride to Colombo to escort their celebrity home. The ladies decorated the train station in grand style for the reception, with thousands of flowers and palm leaves folded in decorative patterns. A new podium was built for the event, where dignitaries would give welcoming speeches and the pandit would offer his first address to the people of Jaffna. Each important religious and social group, and there are many in this region, brought lavish garlands with which to honor him. The air was thick with incense and the redolent perfume of roses and jasmine. As his arrival time neared, more and more people crowded onto the platform. §

Meanwhile, on the train, Rajayogi was conversing with his hosts, noting how good it felt to be home again. But when the train stopped at Palai railway station, he suddenly fell silent, closed his eyes and entered a deep, blissful state. His face glowed with contentment. After a few moments he opened his eyes, clearly overwhelmed with his experience. §

The head of the entourage asked, “What happened? Are you all right?” Rajayogi sighed, “I felt a great jyoti board at the last station. That light is pervading the train.” He turned inward again, relishing that darshan for the rest of the trip. §

At the Pungangkulam station just before the Jaffna depot, he felt the jyoti leaving the train. He asked his hosts who it was. One looked out the window and, seeing Yogaswami walking away, pointed him out to Rajayogi, explaining, “He’s just an ascetic who lives in a village near here.” §

The train was ready to leave the station. Rajayogi insisted on getting off then and there. No reception would hold him. This was what was important for his life right now. He had to meet the being whose spiritual illumination he had felt so palpably. §

His hosts stood confounded. Their duty was to get Rajayogi to the grand reception just a few kilometers away. Hundreds of people were waiting. They would be to blame if they were late or if anything went amiss. He understood their predicament, but still insisted on seeing Yogaswami. He urged, “Please just let me off the train. Simply postpone the reception until the evening, when I am scheduled to speak. I will take the blame.” His hosts were just as adamant, promising they would cut the reception short and personally take him to see Yogaswami immediately afterward. Rajayogi relented as the train started up with a jerk and chugged forward to Jaffna. §

Now the men had pause for thought. Why was the famous Rajayogi so enamored with Yogaswami? They had felt no special power from him all these years. To them, he was an enigmatic sadhu to be feared and avoided. Now here was Rajayogi ready to dispense with all the honors of friends awaiting him for a moment with a stranger. The reception would be the finest Jaffna had held in decades, and he wanted to push it aside to see Yogaswami! §

As they pulled into Jaffna station, the platform was overflowing with townfolk. Musicians were playing tavil drums and the nagasvara woodwind in a frenzy of festive rhythms. Rajayogi was greeted in grand style. Garland after garland was placed on him, so many that they had to be removed quickly to make room for more. §

One day a highly respected pandit named Rajayogi was riding on a train from Colombo to Jaffna when he felt a great jyoti nearby. He inquired about the source of this spiritual power, and a companion reported he saw Yogaswami disembarking at the station before Jaffna. Astonished by the shakti he felt, the pandit pursued.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • §

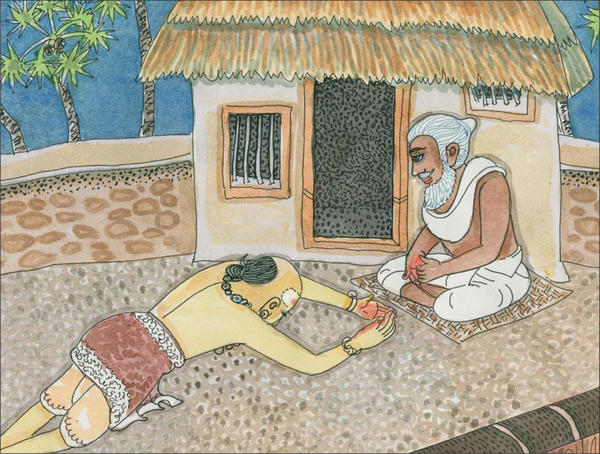

In keeping with their promise, his hosts arranged, against stern objections, to postpone the main part of the reception until that evening. Rajayogi insisted they leave as quickly as possible. He gave a short, eloquent and humorous talk that satisfied the crowd, apologized for curtailing the program, then set out by car with his hosts to find Swami. §

They squeezed into one of Lanka’s ubiquitous black Ambassador sedans and headed for Columbuthurai. Reaching Swami’s hut, Rajayogi, hands held together over his head in the highest form of namaskara, approached the sage and prostrated on the ground. He remained face down on the ground for a long time, then stood in speechless awe. Yogaswami greeted him warmly and offered a seat. §

After a few moments of intense silence, Rajayogi spoke up, “I have never felt such peace as I do at this moment.” Yogaswami responded, “What you feel is within you. I am within you.” They talked together and sat for a time in intimate quietude. Then Swami announced that it was time for Rajayogi to go. Knowing that people would be curious, Swami advised that he not talk about their meeting. “Secret is sacred, and sacred is secret. You are the only one. Know that by keeping a secret.” §

That night, as he mixed with Jaffna’s citizens at the reception, Rajayogi uttered nary a word of his encounter with Swami. But everyone knew. That’s the way things are in Jaffna. His companions, unable to contain their enthusiasm, chattered about how their renowned pandit had recognized Yogaswami as his guru. §

This was a turning point; others became aware of Swami’s rare spirituality and began coming to him. Not in great numbers; he was so aloof, disengaged and difficult to approach. He lived an austere, reclusive life, constantly immersed in tapas, consciously cutting away every thread of attachment so that he could soar to the apex of existence, beyond time, form, space and any movement of the mind. §

Working with Seekers

Chellappaswami had never allowed himself to be known as a guru. Yogaswami knew the wisdom of that position. He understood that those who open themselves too soon and take on disciples before reaching sufficient maturity and stability in the highest chakras may develop into proud, self-serving men. Reaching an intermediary plateau in their unfoldment, they open themselves prematurely, stop their tapas and spend all their time trying to bring others along the path. §

No matter how noble their intentions, these swamis are brought into unexpected suffering by the crowds who gather around them. They have neither the humility nor maturity to deal with the adoration and adulation that come and carry these to the altar of the Supreme One within. Instead, they fall prey to spiritual pride and develop a new, worldly ego that closes the door to their own progress on the path and renders them useless in any effort to guide others. §

Swami would not stumble into that abyss. Thus, during this time he strove to purify himself, to complete his transformation and establish himself so firmly in the Self that he could serve as a worthy channel for God Siva and all the Deities, devas and gurus living on the inner planes who assist and work through a satguru on Earth. He sat deep in samadhi, realizing the Self, Absolute Reality, again and again and again. He spent his time around holy places, communing with the transcendental forces or pilgrimaging from one place to another in obedience to inner orders. §

Inthumathy Amma wrote of this period when more and more devotees began gathering around him: §

Rajayogi visited the sage at his hut and fell at the stranger’s feet, acknowledging his greatness and thereby informing the world of Yogaswami’s stature. Because a pandit of his stature had prostrated, the entire community became aware of the great soul who was living in their midst.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • §

In a short time there was a big change in Siva Yogar’s attitude. Early morning one could hear the sounds of the compound in front of the hut. The floor of the hut was smeared with cow dung and appeared very clean. It was no longer a dilapidated hut where snakes dwelt. In the northern room the divine sandals appeared bedecked with flowers. §

Whenever Siva Yogar was seen on the road, his glistening silver white hair was tied into a neat knot. The holy ash which he generously spread on his forehead shone in the sunlight. The shawl thrown over his shoulder dangled in a delightful way. He had in his hand an umbrella, a symbol of his protection to all. §

At that time he frequented the then famous Shanmuganathan Book Depot. Those coming there in search of knowledge were attracted by Swami, the embodiment of wisdom. To those mature souls he would say, “Instead of delving deep into the sciences and arts, turn your mind within you and study the heart within you.” Some of Swami’s other favorite places were the Vivekananda Press at Vannarpannai and the Navalar Printing Press and Book Depot.§

Siva Yogaswami sometimes went to the house of the native physician Kasturi Muthukumaru, an ayurvedic doctor who not only treated the poor and needy free, but also gave them travel expenses if they came from far-off places. Those who went there not only received medicines from a famous physician but they also had the good fortune to receive the grace of Siva Yogaswami, who was the embodiment of compassion. §

Mr. V. Rajasekharam recalled how word spread of Yogaswami’s greatness in these early years of his four decades of spiritual prominence:§

About the year 1925, many people from Jaffna began to utter Yogaswami’s name with great devotion and piety. People started to talk of him as a sage “who knows past, present and future.” In the peninsula where there were no mountains, he was resplendent as a mountain of grace and compassion. Having heard these words, I too greatly desired to see him.§

As word got around of Swami’s yogic powers, people came to him as a soothsayer, astrologer or fortune teller. “Swami, I am considering a move to Colombo, where I have been offered a position at the University. What do you see in my future? Will it work out well for me?” Such queries—grounded in the fear that something might be taken from them or they might have a bad experience—were rejected and addressed with a fiery scolding. He invariably pointed out their blatant misunderstanding: “At no point in your life have you ever not had what you needed. All that we need is freely given to us. We only suffer because we are not aware that we need what we have received.” §

Swami was pointing out the importance of accepting each of life’s experiences, whether seemingly harsh or happy, as our perfect next step on the spiritual path. Many who received such severe scolding, who endured Swami’s reprimands, confided they were never afraid of anything else the rest of their lives. Swami had shaken them to the core as no mere change in fortune ever could. One close devotee, Dr. S. Ramanathan of Chunnakam, recounted:§

Swami would explain the science of the movement of stars and zodiacal signs. He would say that one of his students, Justice Akbar, knew this science very well. If anyone asked about astrological matters, Swami would say that he was not an astrologer. I saw the lines on Swami’s palms; they were crystal clear. When I asked to examine his palm, he refused, saying “What use is there for astrology or the other sciences that predict the future to one who believes that all is Siva’s doings and who does not worry about the morrow and is a witness to all that happens?”§

As sincere devotees who were devout and grounded in the philosophy came for guidance, he took an active role in their lives. He would go to them, even pester them. Once Swami arrived at a devotee’s home early in the morning, went inside and sat by the man’s bed until he awoke from sleep. As he opened his eyes, there was Yogaswami, demanding, “Where did you go in your dreams? I know where you went, and it was not where you should be going! You need only come to me from now on!” meaning that he should be as pure during his dreams as he tries to be in his wakeful hours. Then Swami watched as the man performed his morning puja, bluntly correcting him for any action he did carelessly or without devotion. Only after this puja to the Gods did he allow the man to worship him as the guru. §

Devotees fell at Yogaswami’s feet each day in the hut, while he took refuge in his guru’s sandals, kept in a small shrine. Sometimes, in meditation, he heard the silver anklets of the Goddess as She danced in the Sivaloka.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • §

It was not unusual for Swami to focus on a devotee in this way for several days to convey personal, life-changing lessons, just as Chellappaswami had done with him. Now and again through the day, Swami would remind the devotee to be the watcher: “You are not your body. You are not your mind. You are not your emotions. You are the atma. That only is. Be that and be a witness!” To help devotees live such a detached life, he urged them to be like the tamarind fruit. As this fruit matures, it dries and shrinks, loosening itself from the hard pod in which it grows. When ripe, it is completely detached from the pod, touching it only at the point where the pod joins the tree. §

Yogaswami was especially fond of Pundit K. Navaratnam, an effective school teacher who inspired the most unmotivated students to be attentive and strive to live informed, productive lives. Swami often arrived at his home early in the morning. They would sit together quietly for some time, then go on long walks before school opened. On occasion, Swami would wait in the park outside the school in case the teacher had some free time. While he sat there, people gathered around him and sang holy songs. The melodies would waft into the classrooms. The two sometimes sat with devotees in Muttavalli and read books by Swami Vivekananda and Aurobindo. §

Swami encouraged Navaratnam’s scholarly skills and brought books for him to read. One day Swami told him he should write books himself about Hinduism, to be read by those coming to Hinduism from the West. Hence, through the years Pundit wrote excellent books about many aspects of Hinduism, most notably Studies in Hinduism. Swami forbade him to mention his name, though, so the books mentioned many sages and saints, but not Yogaswami. §

Pundit was a popular mentor for most of the principals and teachers of Jaffna schools. He was so respected by the Hindu community that he was given the title Kalaipulavar, meaning a master in poems and songs related to Tamil literature and Hindu philosophy. On the night of Mahasivaratri in 1927, he and Yogaswami sat together in meditation from 6pm to 5am.§