Chapter Nine

Yoganathan Is Transformed

After Yoganathan left school in 1888, his father, Ambalavanar, took him to Maskeliya, where he worked as a tobacco merchant, 350 kilometers from Jaffna, in the southern highlands, due east from Colombo. The father hoped his son would settle down and learn the merchant trade. Ultimately, he was disappointed, as the young man was too fond of sitting alone outdoors, bare-chested, on a large rock, meditating and enjoying the tropical, mountain beauty of the region. Around 1890, his father sent him back to Columbuthurai, realizing he had little interest in following the family trade. Ambalavanar passed away in Maskeliya in 1892. §

Within a few months of his return to Jaffna, Yoganathan took a job with the Public Works Department, Irrigation Section, in Kilinochchi, a farming community seventy-two kilometers south of Jaffna. Ratna Ma Navaratnam explains in Saint Yogaswami and the Testament of Truth:§

In pursuance of the colonial policy of opening up the Dry Zone areas for the cultivation of paddy, and the persistent efforts of Sir Ponnambalam Ramanathan, who represented the Tamil community in the Legislative Council of Colonial Ceylon, the Iranamadu Tank project was mooted out in the Kilinochchi area in the last decade of the nineteenth century.§

Working for Mr. Brown

One large reservoir was to be established by combining existing smaller bodies of water. The Iranamadu project was first proposed by government agent Mr. Duke to the Governor of Ceylon, His Excellency Sir Henry Ward, when Ward visited Jaffna in 1856. Mr. Parker, an irrigation engineer, submitted the final proposal in 1866. Completed in 1920 and expanded in later decades, the massive reservoir is now 9½ kilometers in length north to south and two kilometers east to west. The Tamils of the arid North have been perennially interested in building and rebuilding water ponds, and irrigation works have been underway in the region for centuries. §

Yoganathan came under the employment of the project supervisor, an English engineer named Mr. Brown, a rough-hewn man who openly expressed his dislike for Tamils, regarding them, as did all his peers, as a class of savage being subservient to superior peoples, such as the British. He took up residence on the site. His wife and children sailed from Liverpool to join him. §

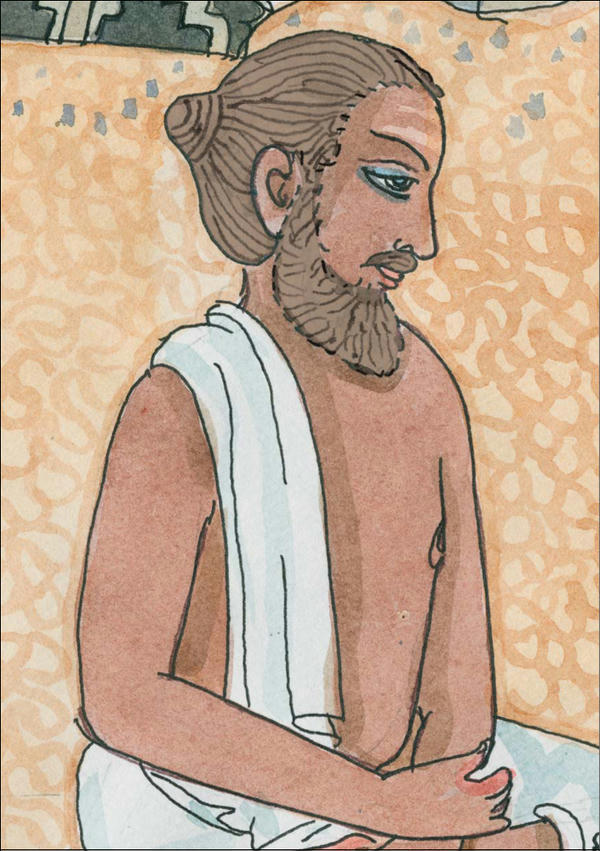

The greatest of souls have biographies, paths followed before they became the saints and sages known by followers. Yoganathan’s young adult years were passed in Kilinochchi, where the satguru-to-be worked on a historic irrigation project, earned a meager pay and spent his private time in spiritual pursuits.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • §

Brown, impressed by Yoganathan’s refined manners and personal discipline, hired him as his storekeeper, a trusted position that allowed some leisure. His new duty was to issue tools to the workers from the company store at the beginning of the day, then collect and care for them at the day’s end. He executed his work with great care. In his off hours, he planted and cared for fruit trees. One mango tree he planted in those days, known as the Swamiyar tree, still flourishes and fruits today, and is eagerly visited by devotees. The land on which the tree is situated was acquired by the Sivathondan Society. §

Yoganathan felt fortunate. The work was not strenuous, and he had his own quarters and free time each day to spend as he pleased. It was a forested area, cooler than around Jaffna, with few houses and lots of peacocks. He soon fit in with the routine and was on good terms with everyone. §

As part of learning the ropes, Yoganathan was warned many times about his employer’s vicious temper. Before long he witnessed incidents of it himself. The slightest offense would provoke Brown to a fury, and he didn’t hesitate to beat his workers if they displeased him. Yoganathan always managed to stay on the outside of this by being extra careful around the volcanic engineer. He watched Brown to discern his mind and learned to be sensitive to his moods. He soon discovered subtle ways of protecting himself. Whenever he felt Brown was upset and about to get angry, he picked up a tool of some kind and simply held it in his hands. That averted any potential attack. §

Yoganathan got along well with him through the years. He knew Brown liked him, because he let him play with his children. Mr. Brown once described him as “a conscientious member of his staff who hurried off to meditate as soon as he finished his work.” Mr. Brown used to address him as “God Man” and often said, “You are a God-fearing man.” Ultimately they grew so close that Yoganathan started teaching the Tamil language to Mr. Brown. §

There were qualities that Yoganathan admired in Mr. Brown as well. He had a keen sense of duty and wouldn’t neglect or put off even the smallest matters. He took personal responsibility for everything that went on at Iranamadu, and this kept the work moving ahead through every difficulty. Through the years, Yoganathan saw everything at the project—hundreds of men, supplies, livestock, accounts, engineering—turning like clockwork around one man who held duty sacred. It impressed him. §

About fifty bulls were attached to the project to do the hauling and heavy work. Mr. Brown insisted they receive the best of care and did not permit them to be abused. After the day’s work, their drivers led them to the river to wash and feed them, and every day Mr. Brown walked down to see that they did it right. It was a lesson Yoganathan never forgot. §

Life at the irrigation company in Kilinochchi had its dark side and difficulties. Aloof from the staff, Yoganathan was hassled by one among them, a bully who took every opportunity to taunt his brown-skinned junior. Months of this wore on, and one day, in the fury of an encounter, the bully threatened Yoganathan, not knowing that inside his younger victim a fire was smoldering. A fight ensued during which Yoganathan stabbed the aggressor. It was a terrible event, and Mr. Brown took it seriously. Yoganathan was ordered to serve six weeks of hard labor at the nearby Mankulam Quarry. §

Meanwhile, Uncle Chinnaiya tried repeatedly to arrange a match for the young man, but Yoganathan wanted no part of it. He felt his path lay elsewhere. He spent his money on scriptures, books of hymns and stories of the Saivite saints. He studied these over and over again, never content until he could establish within himself the truth of the words he read. It awed him to think that life in this world could be lived with such purity and devotion. He knew the stories of the saints by heart and was forever singing their Devarams. §

In order to study Sanskrit scriptures, he acquired proficiency in Sanskrit during these years as well. Kilinochchi afforded him the peaceful surroundings he needed for the study and worship he so valued. Yoganathan made good use of his time. He spent his days off alone in contemplative settings and was a constant visitor at all the nearby temples. People were amazed at how well and how deeply he knew the many scriptures of Hinduism. He could recite them page by page. §

Mornings and evenings he meditated on what he read, and gradually he built up a daily routine of sadhanas. He added to these disciplines from time to time, and as his meditations deepened he took up various kinds of tapas as well. Sometime during his years in Kilinochchi, he took a formal vow of celibacy to affirm his commitment to the spiritual path and his decision, despite family efforts to the contrary, never to marry. §

Inthumathy Amma notes:§

Years later he told his devotees that he cultivated the habit of spending everything he earned in that month itself without saving anything for a rainy day. Except for his meager personal expenses, he spent the rest of the money on temples, friends, relations and the poor and needy.§

While Yoganathan was employed at Iranamadu, a crucial event occurred that nurtured his inclinations to renounce the world. Ratna Ma Navaratnam wrote: §

At about this time, the triumphant return of Swami Vivekananda from the World’s Parliament of Religions at Chicago created a stir in the hearts of the people enticed by alien culture, and his visit to Ceylon was acclaimed as a happy augury for the renewal of faith in Hinduism. The prophet of the New Age came to Yalpanam in 1897, and his elevating lectures at Hindu College, the Esplanade and the Saiva Pathashala at Columbuthurai made an undying impression on Swami.§

It is reported that when Swami Vivekananda was ceremoniously brought in a carriage drawn by the leading Hindu citizens to address the public at the present Hindu Maha Vidyalaya at Columbuthurai, he got down from the carriage at the junction where stands the illupai tree and walked up to the school. In his lecture, he reported that he was impelled to get down from the carriage, as he felt he was treading on sanctified soil and called it, prophetically, an oasis. This was the illupai tree under whose shade Swami would later sit in the sun and rain during his sadhana years. Columbuthurai was singled out as an attractive oasis when Swami in later years, too, hallowed this spot as his religious centre and ashram. §

Inthumathy Amma adds to the chronicle:§

When Swami was working in Kilinochchi, Swami Vivekananda’s visit to Ceylon took place (1897). Swami participated in the reception that Jaffna accorded to him with great enthusiasm. Swami also took part in the procession from the Fort to Hindu College, and later in the public meeting held at the Hindu College premises. §

The eagerness with which Swami later spoke of the topics discussed by Swami Vivekananda in those early days showed the great latent desire he had for the company of saints.§

Yoganathan lived like a yogi in Kilinochchi, alone unto himself, immersed in his meditations. He spoke little, for his interests were not those of the people around him. He carefully protected his inner experiences. By his third year in Kilinochchi, he was well settled in his job, executing his duties quietly and well, letting nothing disturb his inner work. He frequently sat up late into the night studying scriptures, singing hymns or meditating by the light of a single oil lamp. He was in the world, but less and less of it. §

One thought took root early on and eventually quelled all other plans—the desire to renounce the world and seek Realization of God undistracted. It made sense to him. Everything he had ever done, everything he had become, led in that direction. That alone intrigued and inspired him. But he knew he had to find a satguru, a jnani, to guide him. The scriptures are adamant: except through the grace of a living satguru, a man of Realization, the path to the Self is not seen in this world. Yoganathan didn’t know anyone like that, so he hesitated, watching and waiting. It is traditional knowledge in Saivism that the guru cannot fail to appear when the disciple is ready, “ripe for grace.” §

Yoganathan knew this to his core. He had learned of the process in the hymns and life of Saint Manikkavasagar. At the age of eighteen Manikkavasagar was the Prime Minister of the Pandyan empire, young, brilliant and wealthy. Though he had everything, he yearned only for a guru to lead him from darkness to light. The moment he laid eyes on his teacher, he was powerless but to follow, as he recognized the object of his soul’s search. He then abandoned all—family, friends, fortune and fame. Many such saintly lives Yoganathan had pondered, and he knew that finding a guru was not entirely in his hands. When he was ready, the guru would appear. He went on with his sadhana. He continued to work, and he prayed for a guru, prayed again and again. §

Chinnaiya felt it increasingly urgent to broach the subject of marriage. Yoganathan understood the cultural pulls on him and avoided his uncle. He would find something to do elsewhere if he thought Chinnaiya might visit that day. Though he had long since decided to take sannyasa and thus enter fully the spiritual, monastic life he so admired, he hadn’t mentioned this to his relatives. He was his usual, congenial self around them, though he was doing severe tapas of one kind or another every day.§

In his private moments, sitting in the store, he sometimes found himself gazing through the open door, torn between staying or leaving that minute—walking away from the world, from Mr. Brown, from Kilinochchi, from everything. He yearned to be on his way, but something held him back, and in his heart he knew it was Siva’s will. He endured by working harder on the inside, and his sadhana seemed to take on a life of its own. Every spare moment found him sitting quietly in his room or in a temple. He felt he had come to the end of everything, as if he had done all he could do. Sometimes he sat through the whole night in meditation, perfectly still, not moving once. On days when he was free, he would pick a far-off temple and walk there all the way from Kilinochchi without stopping, worship and walk back, singing hymns along the way. At Nallur Temple in Jaffna, he worshiped Lord Murugan, the first renunciate. §

Meeting the Sage of Nallur

One day Vithanayar, his brother Ramalingam and Thuraiappah came to visit Yoganathan, and together they set out walking to Nallur. A man of similar interests, Vithanayar also did sadhana. In fact, being the elder of the two, he felt a certain duty to help Yoganathan forward on the path however and whenever he could. It was the day of the chariot festival in August, an auspicious time to worship Lord Murugan, who would be paraded around the temple in His elaborate chariot. They bathed at the well, put on holy ash and set out for Nallur. Vithanayar hoped they would see Chellappaswami as well.§

On their way, Yoganathan told Vithanayar of an encounter he had with Chellappaswami many years earlier. He was about twelve at the time. Suffering from an infected cut on his foot, he was on his way to the doctor’s hut in Jaffna town. As he passed by the teradi at Nallur Temple, a man shouted, “Come here! What do you want with medicine?” It was Chellappaswami, who beckoned him closer and had him sit down while he examined the wound, nodding his head like a doctor. Chellappaswami told him not to go to the ayurvedic doctor, but to mash a certain herb and apply it as a poultice to the wound. The foot healed in a few days. That was the only time Yoganathan had been near the sage as a child, though he undoubtedly saw him from time to time around Nallur Temple through the years. §

It is said that at age ten or twelve, Yoganathan had also met Kadaitswami in Jaffna town, among the shops. The boy had a high fever and Kadaitswami just touched him, after which the fever gradually subsided. §

A little before noon, Yoganathan and his friends reached Nallur and stepped into a huge crowd, a hundred thousand or more, gathered for the festival. Despite the sweltering midday heat, the temple compound was filled. Hundreds were moving about in front of the temple, awaiting a chance to get inside. Bare-chested men and boys rolled in the hot sand around its outer walls as a penance or sadhana, and devotees followed them singing. §

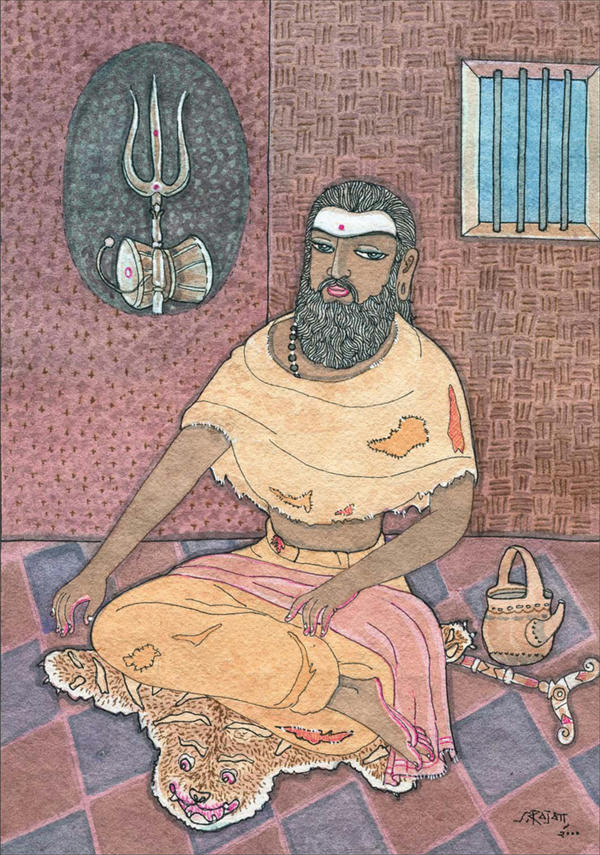

It is said that Hindu holy men fall into two main categories: those who are pious, pure and of a saintly demeanor, and those who are sagely, homeless and even odd. Chellappaswami was more sage than saint, with his disheveled veshti, his unkempt body and his strange behaviors. Still, he was known as a guru of the highest order.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • §

A mingling aroma of incense and flowers perfumed the air, while a chorus of voices rose from the sea of umbrellas spanning the dusty square between the teradi and temple. In the tropics, umbrellas are not for rain alone, but more often to give protection from the penetrating sun. Out from the open doors of the sanctum came crescendos of shrill woodwinds, kinetic drums and bells, driven on by the chanting of the brahmins. Pujas had been going on from daybreak, and the air was intensely charged with Lord Murugan’s presence. §

The mandapam was packed with thousands of devotees, jostling and pushing to stand closer to the puja. Yoganathan and his three friends worked their way toward the teradi, where they hoped to see Chellappaswami. Before they knew it, the crowd parted, and there he was, not three meters away, standing among the devotees, challenging and powerful. His gaunt figure stood out sharply against the crowd, seeming somehow taller than his five feet nine inches. §

Everyone walked around him without coming near, intimidated by his striking appearance. He was barefoot, thin-bearded and burnt dark by the sun, wearing a single white cloth, wrapped once, from the waist down. Surveying the multitudes with transparent glee, he was talking aloud to no one at all, blithely unaware of the looks he drew. He carried himself with a lion’s air of dominion and power. A penniless sadhu, he stood like a king, his posture at odds with his conduct and dress. §

He spotted the four visitors just before they saw him and walked toward the teradi. They greeted him humbly. Yoganathan’s friends had visited Chellappaswami many times, and Yoganathan could not help but be keenly aware of the majestic being; but now he was standing face to face with the great one. §

After a few moments Chellappaswami dismissed the three householders, shouting, “Go and look after your families! You fellows are not fit to become sadhus.” Yoganathan, on the other hand, he kindly invited to stay back: “I was awaiting your arrival here. I am going to have a coronation for you soon.” Drawing Yoganathan to his side, he gave him instruction in spiritual values, then suddenly slapped him on the head with his right hand, exclaiming, “This is the coronation!” and voiced five momentous teachings: §

Summa iru. (Be still.)

Eppavo mudintha kaariyam. (It was all finished long ago.)

Naam ariyom. (We know not.)

Muluthum unmai. (All is truth.)

Oru pollupumillai. (There is not one wrong thing.)§

Yogaswami later wrote:§

Then and there I received divine grace. Once these words were imprinted in the heart of the devotee, Chellappah with his face blossoming with grace said, “It is good, dear one; come, I have been waiting for a person like you.” §

That evening at sunset, still overwhelmed by the encounter, Yoganathan walked back alone to his aunt’s house. Those who recalled those times said that following this experience the young man met often with Chellappaswami on weekend trips from Kilinochchi.§

Moment of Truth

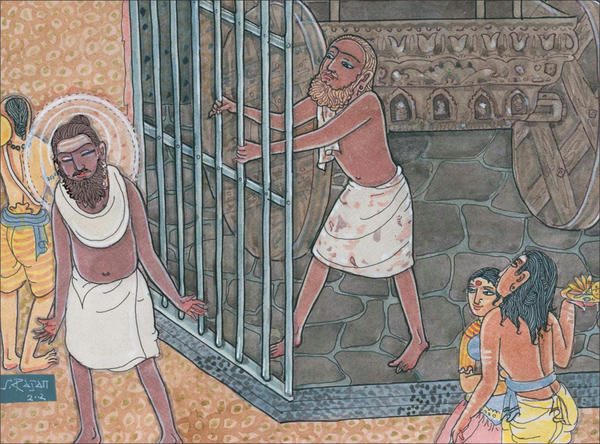

A subsequent meeting, which Yogaswami described years later in his Natchintanai, was equally transformative. Yoganathan was walking along the road outside Nallur Temple. Sage Chellappaswami shook the bars from within the chariot shed where he camped and boldly challenged, “Hey! Who are you?” (Yaaradaa nee?). §

Yoganathan was transfixed by the simple, piercing inquiry. Their eyes met and Yoganathan froze. Chellappaswami’s glance went right to his soul. The sage’s eyes were like diamonds, fiery and sharp, and they held his with such intensity that Yoganathan felt his breathing stop, his stomach in a knot, his heart pounding in his ears. He stared back at Chellappaswami. Once he blinked, in the glaring sun, and a brilliant inner light burst behind his eyes. §

He revealed to me Reality without end or beginning and enclosed me in the subtlety of the state of summa. All sorrow disappeared; all happiness disappeared! Light! Light! Light!§

Waves of bliss swept his limbs from head to toe, riveting his attention within. He had never known such beauty or power. For what seemed ages it thundered and shook him while he stood motionless, lost to the world. He later described it as a trance. §

To end my endless turning on the wheel of wretched birth, he took me beneath his rule, and I was drowned in bliss. Leaving charity and tapas, charya and kriya, by fourfold means he made me as himself.§

The roaring of the nada nadi shakti—the mystic, high-pitched inner sound of the Eternal—in his head drowned out all else. The temple bells faded in the circling distance as from every side an ocean of light rushed in, billowing and rolling down upon his head. He couldn’t hold on, not for an instant. He let go, and Divinity absorbed him. It was him, and he was not. §

By the guru’s grace, I won the bliss in which I knew no other. I attained the silence where illusion is no more. I understood the Lord, who stands devoid of action. From the eightfold yoga I was freed.§

Yoganathan stood transfixed, like a statue, for several minutes. As he regained normal consciousness and opened his eyes, Chellappaswami was waiting, glaring at him fiercely. “Give up desire!” he shouted. People were passing to and fro, unaware of what was taking place. “Do not even desire to have no desire!” §

Yoganathan felt the grace of the guru pour over and through him, all from those piercing eyes. Such elation he had never known. Dazed, he saw that the guru intended to dispel all darkness and delusion with his words, which were beyond comprehension in that moment: “There is no intrinsic evil. There is not one wrong thing!” §

Yogaswami later wrote of this dramatic meeting in a song called “I Saw My Guru at Nallur:”§

Yogaswami wrote often of the day his life was transformed. Passing the Nallur chariot house that morning, he was transfixed by Chellappaswami’s holy presence. When the guru challenged, “Hey! Who are you?” the disciple was lost in an infinite light that engulfed him and changed him forever.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •§

I saw my guru at Nallur, where great tapasvins dwell. Many unutterable words he uttered, but I stood unaffected. “Hey! Who are you?” he challenged me. That very day itself his grace I came to win. §

I entered within the splendor of his grace. There I saw darkness all-surrounding. I could not comprehend the meaning. §

“There is not one wrong thing,” he said. I heard him and stood bewildered, not fathoming the secret. §

As I stood in perplexity, he looked at me with kindness, and the maya that was tormenting me left me and disappeared. §

He pointed above my head and spoke in Skanda’s forecourt. I lost all consciousness of body and stood there in amazement. §

While I remained in wonderment, he courteously expounded the essence of Vedanta, that my fear might disappear. “It is as it is. Who knows? Grasp well the meaning of these words,” he said, and looked me keenly in the face—that peerless one, who such great tapas has achieved! §

In this world all my relations vanished. My brothers and my parents disappeared. And by the grace of my guru, who has no one to compare with him, I remained with no one to compare with me.§

As Yoganathan tried to comprehend the experience, his guru had already forgotten him there. Chellappaswami was scanning distant rooftops, mumbling to himself and nodding in accord with all he was saying, then began walking away. Yoganathan started to follow when the sage called back over his shoulder, “Wait here ’till I return!” §

It was three full days before his guru came back, and the determined Yoganathan was still standing right where he left him. Chellappaswami didn’t speak or even stop. He motioned for Yoganathan to follow, leading him to the open fire pit where the sadhu prepared his own meals. There he served Yoganathan tea and a curried vegetable stew, then sent him away. §

He didn’t welcome or praise his new disciple; he didn’t say to come back or not to come back. He didn’t have to. Yoganathan knew he had been accepted. And his training began—the first chance he got, he bent to touch Chellappaswami’s feet, and his guru bellowed in dismay. Drawing back, the sage scolded him, “Don’t even think of it!” Yoganathan was bewildered, but he obeyed, and his guru calmed down. “You and I are one,” he said. “If you see me as separate from you, you will get into trouble.”§

Chellappaswami’s insistence on the oneness of guru and disciple, in fact the oneness of everything, while strange to the average man, was a faithful expression of the ancient Agama texts, which decree: §

“Siva is different from me. Actually, I am different from Siva.” The highly refined seeker should avoid such vicious notions of difference. “He who is Siva is indeed Myself.” Let him always contemplate this non-dual union between Siva and himself.§

With one-pointed meditation of such non-dual unity, one gets himself established within his own Self, always and everywhere. Being established within himself, he directly sees the Lord, who is within every soul and within every object and who presents Himself in all the manifested bodies. There is no doubt about the occurrence of such experience.§

He who is declared in all the authentic scriptures as unborn, the creator and controller of the universe, the One who is not associated with a body evolved from maya, the One who is free from the qualities evolved from maya and who is the Self of all, is indeed Myself. There is no doubt about this nondual union.§

Sarvajnanottara Agama 2.13-16§

Yoganathan was utterly devoted to Chellappaswami. In later life he expressed his profound reverence in many of his songs and writings, called Natchintanai, such as the following:§

Come, offer worship, O my mind, to Gurunathan’s holy feet, who said, “There is not one wrong thing,” and comforted my heart. Come swiftly, swiftly, O my mind, that I may adore the lord who on me certainty bestowed by saying “All is truth.” Let us with confidence, O my mind, hasten to visit him who at Nallur upon that day “We do not know” declared. §

Come soon and quickly, O my mind, Chellappan to see, who ever and anon repeats, “It is as it is.” Come, O my mind, to sing of him who near the chariot proclaimed, “Who knows?” with glad and joyful heart for all the world to know. Come now to Nallur, O my mind, the satguru to praise, the king of lions on tapas’s path whom nobody can gauge. Come with gladness, O my mind, our father to behold, who of lust and anger is devoid, and in tattered rags is clothed. §

Please come and follow me, O mind, to see the beauteous one, who mantras and tantras does not know, nor honor or disgrace. Come, O my mind, to give your love to the guru, free from fear, who like a madman roamed about, desiring only alms. Come, O my mind, to join with him who grants unchanging grace and is the Lord who far above the thirty-six tattvas stands.§

Spiritual Work in Kilinochchi

After his life-altering experience, Yoganathan returned to his work at Kilinochchi, while pilgrimaging the full sixty-five kilometers to Nallur each weekend to be with his satguru, and again walking back in time to fulfill his morning duties on Monday. However, his heart ached to leave his job, to let go of the rope, to be with his guru at Nallur. The strenuous effort he poured into his sadhana was all that allowed him to stick with the routine at Iranamadu. §

No tapas was too harsh. One day, many years later, a young man came to visit the sage who had come to be known as Yogaswami. They talked for a few minutes, and the man mentioned that, to purify himself, he had been rubbing chili powder over his body and then sitting in the hot sun. Yogaswami’s eyes lit up, “A fine tapas! I, too, have done that!” Ratna Ma Navaratnam, in Saint Yogaswami and the Testament of Truth, recounts: §

It is believed that at the beginning of this century Swami experienced spells of spiritual insights and felt powerfully drawn to his guru. During this time, a select coterie from Columbuthurai including the Vidhane Thirugnanasampanthar, Kadirithamby Vettivelu, Ponniah Upadiyayar, Sivagurunathar Thuraiappah and Thiagar Ponniah would visit Chellappar at Nallur quite frequently. Swami would join them whenever he came down from his sphere of work. He would at times recall how vigorously he used to walk all the forty-five miles from Kilinochchi to Nallur to meet Chellappar, for so great was his urge to be in the living presence of his guru.§

At his workplace Yoganathan spent his free time during the week deeply immersed in his guru’s teachings and in his sadhana. Inthumathy Amma describes those days: §

The Kilinochchi forest became an apt ashram for Swami to sit peacefully and cogitate and practice all that he had learned from Chellappaswami. By thinking deeply for long hours, by entering into deep niddai [a state of immersion in the Divine], by sitting in meditation and by following the yogic disciplines, he practiced all he had learned from his guru. His chief object was “to know himself.” He studied the book that was within him carefully, with great alertness. He would look at his religious books only occasionally, and that, too, as a means of spending some leisure time. As he became more and more mature in his sadhana, he began to experience the treasure of being seated in yoga and the bliss of meditation. §

Swami always remembered Kilinochchi as his training ground to lead a life of happiness mingled with God. In later days, while traveling with his devotees through that area, he would point out the place where he practiced his yoga and say, “This place is extremely suitable for meditation.” §

Near the end of 1897, Yoganathan decided to quit his job to immerse himself completely in his guru’s holy presence. S. Ampikaipaakan observed: §

In Swamikal’s life the year 1897 was very important. It seems Swamikal quit His job at the end of that year and returned to Jaffna. Swamikal was about twenty-five years old. That was the time Swamikal progressed step by step in the religious life.§

Inthumathy Amma writes of this transformative time: §

The insatiable love for Chellappa Desikar, the benevolent guru, full of grace, who was waiting to show him visions that were not visible, began to flourish in Yogamuni [a name for Yogaswami meaning silent sage]. He became astounded at Chellappa, the guru who taught him the path to knowledge and wisdom and who was the great knower “who knew and realized the Veda without any study.” The repetition of his name became sweeter and sweeter. The form of Chellappa became the form he meditated on. His divine feet became the recipients of his worship. His nectaric words were mantric words. Just like a compass always pointing north, whatever work he performed, whatever hardships he endured—his mind was always focused on the chariot house. Yogamuni realized that it was impossible to have light and darkness at the same time and decided to renounce his employment and other worldly affairs. He realized that the company of good sages was better than relations, parents and siblings, and renounced his relatives. Thus he renounced his employment, kith and kin, and went to the chariot house, surrendering himself completely, and remained there at Chellappa’s feet as his good devotee. §

Yoganathan watched until Mr. Brown was in a good mood, then told him he was leaving. The stern Englishman was naturally unhappy about this and tried to dissuade him, but Yoganathan was firm. Brown then tried to postpone it for a year, and finally relented, saying, “If you desire to resign, at least appoint someone like you to take charge of the work.” §

Yoganathan agreed to that. He wasn’t just leaving a job; he was renouncing the world. Brown didn’t know that and wouldn’t understand if he were told. Because Yoganathan didn’t want to leave any upset or imbalance behind, he promised to stay on long enough to train a replacement. He recommended his cousin Vaithialingam, who was just 19. Ever the administrator, Brown promised to hire the youth only if he could perform as well as Yoganathan. Vaithialingam was happy to be offered the job and arrived a few days later. He shared Yoganathan’s simple quarters and imbibed his years of experience during the weeks they were together. §

Vaithialingam remembered well the time he spent with Yoganathan at the company store, and his recollections became the primary source of knowledge about this period in Swami’s life. He was astounded at his cousin’s firm habits and austere lifestyle. The whole family knew he was religious, but because he was living in far-off Kilinochchi, none understood the depth of his seeking. §

Vaithialingam spoke of nights when he woke from a sound sleep to find Yoganathan sitting in yogic pose, pleading aloud for the grace of Siva. Oblivious to the room around him, he would pray to Shakti, the energy aspect of Siva, to rise within him and bring realization. Tears wet his face as he begged for grace, “O my dear mother! O my dear father!” as Vaithialingam lay awake, listening for hours. He said he saw there what the rest of the family had not—that Yoganathan could never be satisfied with an ordinary life in the world. He was determined beyond anyone’s imagining to accomplish what he later said was the only work to be done on this planet—realization of Parasiva. §

Throwing Down the World

The cousins worked together for some time until Brown was fully satisfied with Vaithialingam and told Yoganathan he was free to go. He left Iranamadu to undertake sadhana full time, renounce the world and be with his guru. He was ready. Lifetimes of preparation lay behind him. His tapas and meditations had already shorn the bonds of worldly life. Yoganathan returned to Aunt Muthupillai’s house and received her permission to live in the hut on her land. She was surprised when he told her he intended to renounce the world, but accepted the idea when she saw how serious he was. §

M. Arunasalam tells us about this time in his book Sivayoga Swamiyar: Varalarum Sathanaihallum: §

From the year 1897 to 1900, Yoganathan’s permanent base was the hut at Aunt Muthupillai’s place in Columbuthurai area. From her residence, Yoganathan used to visit Nallur on some days and spend all the daylight hours with his guru, Chellappar. Sometimes Yoganathan would visit Nallur Temple with his friends (Vithanayar, Thuraiappa, etc.). Also during this period, Yoganathan used to walk up to Kilinochchi and practice meditation in quiet areas under the trees. Then again he would walk back to Columbuthurai and stay for a few days, visiting his guru at Nallur Temple. This routine went on until the end of the year 1900. From 1901 to 1910 he underwent vigorous training and sadhanas given by his guru.§

Aside from his jaunts to the hills of Kilinochchi, where he sometimes stayed the weekend with his cousin, Yoganathan’s life was centered in Jaffna. Early each morning he would walk from his aunt’s place to Nallur to spend the day with his guru. Sometimes Chellappaswami sent him away. Was Yogaswami permitted to stay at the teradi with his guru? He was silent on the matter, but some report that for a time, during the period between 1906 and 1910, he did camp with Chellappaswami at Murugan’s chariot house, so that he could be ready early in the morning to set out walking with his guru. What is known is that they were seen each day traveling about and begging for their food. T. Sivayogapathy, son of A. Thillyampalam, narrated what he was told about Yogaswami’s habits during this time:§

From early morning till late evening, he was always with his guru at the Nallur teradi, as well as in surrounding areas of Nallur, and at his guru’s hut, too. Gradually, at the period of the peak of sadhanas, he used to accompany his guru to distant places and return to the teradi, all by walking. Therefore, Yogaswami was compelled to be at his guru’s feet, since his guru had no fixed schedule, and might set out for some distant place quite early in the morning. So, mostly Yogaswami used to spend the night at the teradi steps. He seldom visited his aunt’s place. §

Yogaswami stood by, a silent witness, when he was with his guru. Though, if ever his mind turned to something else, if he thought, “Well, he surely isn’t talking to me,” Chellappaswami would say something to bring him back with a start and let him know that everything his guru did was worthy of his full attention. He always knew what his disciple was thinking, and no matter the time or place or who was around, if Yogaswami entertained a thought Chellappaswami didn’t like, or did something that showed he had ceased to see himself and his guru as one, Chellappaswami would berate him so vehemently, it would have destroyed anyone else. Inthumathy Amma describes this difficult sadhana:§

Chellappa remained the mystery of all mysteries. He would refuse even to look at the devotee who had just worshiped him. He would be angry like death and shout at the devotee who went to revere him with all love. Having been subject to this anger, the devotee would move away and wait with worry while Chellappa ignored him and spoke laughingly with the vagrants who went that way. The minute the devotee thought, “He is talking in jest,” rare mantric [sacred] words would arise. If the devotee went near him, he would attack without any cause. If the devotee went further away, he would attract him. It became necessary to move with him like those sitting before a fire—“not to go too close and not to go too far.” §

The sadhu’s life is difficult, unbroken by the solacing—Yogaswami would say distracting—pleasures ordinary people allow themselves. But there was one indulgence Chellappaswami allowed—their country lane walks. They would amble freely, stride powerfully, exploring their land as though time did not exist, as though they were its kings, roaming widely, unencumbered by even a destination. It was, for them, one of life’s little celebrations. §

Almost every day they were together, begging on village streets or meditating at out-of-the-way places only Chellappaswami knew. They made the rounds of rural shrines and temples in all the outlying villages, sometimes walking for hours to visit a certain one Chellappaswami had in mind that day. There they would sit in the shade and meditate together. But if the feeling wasn’t just right when they arrived, if anything was amiss, Chellappaswami would keep going, to another temple somewhere else. It wasn’t unusual for them to trek all day without stopping, sometimes as far as fifty kilometers. When they returned to Nallur, whether early or late, Chellappaswami would cook a meal for them.§

Chellappaswami again made it clear that he would brook no show of reverence or devotion from Yogaswami. He never once allowed his disciple to serve him, to cook or clean or mend for him. He scolded in a shrill voice if Yogaswami tried to prostrate or even raised his hands in silent namaskara while Chellappaswami’s back was turned. He would know, fiercely chastise and on occasion even kick him if he didn’t stop soon enough. Yogaswami later wrote:§

Hail to the feet of the true guru who took me beneath

his rule and gave himself to me, saying, “Do not

suffer by regarding me as separate from you!Ӥ

Hindu tradition urges the shishya to serve his guru night and day by every means, to wash his clothes, bring meals, run errands, anything to serve him as Siva in human form. Yogaswami knew this and longed to express the grateful love that filled his heart, but Chellappaswami was ruthless in denying him any expression of devotional dualism between guru and disciple. Yogaswami’s training demanded much of him. He loved his guru dearly, but Chellappaswami was hard on the youthful shishya, bringing him slowly to patience, peace, service and spiritual maturity. §

No matter where he was, Chellappaswami talked to himself constantly, as if he were the only person in the world. He rarely said he, she or it, never admitting a second. And he repeated the same obscure phrases over and over again for months on end. While Yogaswami was with him, Chellappaswami once repeated for a whole year, “There is nothing evil in the world. No evil in the world.” Not all that the guru muttered was so exalted. Yogaswami later wrote that Chellappaswami’s soliloquy was a stream of thought that transcended understanding, and one had to listen carefully in order to catch the gems that fell from those lips. §

People who watched the two together wondered how the disciple understood anything at all from the guru. They observed no open exchange between the two. But Yogaswami saw through Chellappaswami’s guise of madness and used every gesture, every word, every look from his guru to refine his own nature, to perfect his sadhana. All his life, Yogaswami marveled at Chellappaswami’s absolute purity. He was so pure, Yogaswami said, that nothing impure could stand in his presence. In the following Natchintanai, “The Master of Nallur,” Yogaswami gives a lucid description: §

He who both like and dislike has exterminated, the noble one who never forgets the holy feet of God, who that “there is not one wrong thing” has openly declared—’tis he indeed who has assumed the guru’s splendid form! He who unceasingly proclaims that all that is is truth, the master who has passed beyond ideas of good and bad, he who sees and looks upon himself and me as one, out of love, upon my head has placed his beauteous feet. §

The exalted seer who by the name of Chellappan is called, who, ever and anon, “Who knows? Who knows?” repeats the madman who will never by the world be known; he will be seated every day upon the chariot-house steps. Dark as the clouds in color, he ever had the habit to sleep upon the earth; his pillow was his hand. In the form of the guru he lived with grace and honor at Nallur, where fresh water and fertile lands abound. The mighty one who has declared for the benefit of all the great and blessed mantra “Nothing do we know,” who delusion, lust and anger has banished from his heart—he bears the name Chellappan, and at Nallur he dwells. §

The crowning jewel beyond compare, who always will repeat that it was all perfected ages long ago, that madman whom nobody is able to describe, in the presence of Lord Murugan he forever lives. At Nallur, where orators and poets bow in worship, my guardian, who made me his and ended birth and death, wears the divine and sacred form of holy Chellappan, who accomplishes his service at Kandaswami’s shrine. §

Inthumathy Amma gives form to Chellappaswami’s formless teaching style in the following summary:§

The sweet drops of honey gleaned from the sweet-scented flower Chellappar by Yogaswami flitting around him can be stated as follows. First, Chellappar taught the path of knowledge by the rare mantric words “Who are you?” (Yaaradaa nee?). Then he taught the path to understanding this by delving deep within oneself with the words “Search within.” (Theydadaa ul) and thus guided him.§

The hindrance to search within was the attachment to the world; hence he said, “Abandon desire” (Theeradaa patrai). He calmed the devotee who, while searching within, found everything enveloped in darkness and was shattered with the words “There is nothing wrong” (Oru pollaappum illai). §

When Yogaswami stood bewildered, not understanding the connotation of the words, “There is no wrong,” the guru took him to the front of the temple of Kandan and, when the curtain was drawn, pointed to the spear (vel) of knowledge and explained the Vedantic truth that once the curtain of illusion is drawn, only Brahman remains. When the devotee was thinking of the mystery of maya, Chellappar gave the mahavakya “See it is as it really is” (Athu appadiyeh ullathai kaan). And to explain that mystery, he said, “Who knows?” (Yaar arivaar?).§

After teaching the path to knowledge, he taught the path of yoga. Master the vaasi [pranayama: control of breath] (Vaasi yogam theyr). Close the two channels (Iru valiyai adakku)—[the two channels are ida and pingala]; transcend the path to birth (Karu valiyai kada); concentrate on the tip of the nose (Naasi nuniyai nohkku); be single-minded in your thoughts; to the land of Kasi go; mount majestically on the fresh and lively horse (Pacchai puraviyiley paangaaga ehru) [a reference to the control of breath]. In the house that is not built by the carpenter [the body], tie the galloping horse (Thacchan kattaa veettiley thaavu pari kattu) [again a reference to control of the breath]. Chellappaswami, who knew without any study all the technical terms used in yoga, taught the nuances and details of the yogic path. He explained to the good acolyte Yogar the different signs and awakenings that occur as one progresses in the practice of yoga.§

He further explained very clearly that once he had transcended the path of birth, the mind would be controlled; that if he concentrated on the tip of the nose and woke up he would see the cosmic dance, and that at another stage he would hear sweet musical sounds. He also encouraged Yogaswami not to abandon the path of devotion that he had practiced earlier, by saying words like, “Wear the rosary” (Akku mani ani); “Repeat the five letters” (Anjeluthai ohthu); “Let the heart melt and melt” (Nekku nekku urugu).§

Guru and disciple were out walking the roads one day. As always, Chellappaswami walked boldly, his eyes gazing ahead, never watching the ground as most people do. It amazed Yogaswami that in the five years they moved about together his guru never stepped on even a single anthill, which were everywhere and which Yogaswami had to diligently dodge during their treks. §

During this outing, Yogaswami noticed his guru was glancing back at him every few minutes. Had he done something wrong? He didn’t think so. Chellappaswami quickened the pace as they approached a village and headed straight for the marketplace. He wandered among the stalls for an hour, pretending to shop and occasionally stealing a glance at Yogaswami. His disciple was quietly waiting. §

They wandered around the village for a while longer, then took a cow trail through the fields. Chellappaswami walked quickly ’till they reached the road, then ambled along, talking to himself and watching his shishya. They turned left at the crossroads and hadn’t walked six meters when the sage spun around, peering suspiciously at Yogaswami: “Why are you following me?” Was Chellappaswami subtly challenging his shishya to examine the deeper purpose of their relationship? §

Chellappaswami was especially particular about his food. Nearly everything he ate he prepared himself, making sure the ingredients were clean and fresh. If anyone looked at his food while he was preparing it or even thought about him while he was cooking or eating, he would stop and discard the meal. His devotees often brought him yams, but he would never eat them. He dug holes in the yard and planted them instead. When the leaves began to appear, he would ask his sister to pick and cook them for him. Similarly, he was extremely sensitive to the vibrations people put into anything they offered him. §

Among his devotees was the chief priest of the Nallur Kailasanatha Sivan Temple, an orthodox brahmin man who strictly observed the rules of his caste. His home was adjacent to the temple. One day, when he looked up to see Chellappaswami walking past his house, he called out and invited the sage to come in and share some milk rice he had just brought from the puja. He knew Chellappaswami’s habits and was afraid he might refuse. To his surprise, the guru came inside to partake. §

When the pongal was offered, Chellappaswami made a sour face and said he wouldn’t eat leftovers. “Someone has already eaten from it.” The priest said, “No, no, no. No one has even looked at it.” He had brought it straight from the sanctum, he pleaded, where he had done the puja himself. But Chellappaswami insisted. The man called his wife, who had prepared the rice in the kitchen, and asked her if anyone had touched it. She was positive no one had, but just to be sure, she suggested they call their small son to see if he had somehow gotten into it before it went to the temple. When they asked him, he hung his head and confessed he had indeed picked a morsel from the dish before his father took it to offer during puja. §

Most people in Jaffna were sure Chellappaswami was completely mad, or at least too wild a sadhu to approach for blessings. Yogaswami had seen through his disguise that first day at Nallur. That moment of recognition—the look in Chellappaswami’s eyes, full of the intent to take this young man to the heights of realization—lived within him and was all the assurance he ever needed. To Yogaswami, everything he had ever wanted had already been accomplished in that moment. It was simply unfolding itself in the months that followed. His first year with Chellappaswami was the natural unfoldment of that first moment. He followed after the guru wherever he would permit, listening, watching, waiting for the quiet word or glance that would tell him what was wanted. Whether he was awake or asleep, Yogaswami’s thoughts turned ’round his guru and the magic of his grace.§