A Tribute to Indian Dress

THOMAS KELLY§

BY THE EDITOR§

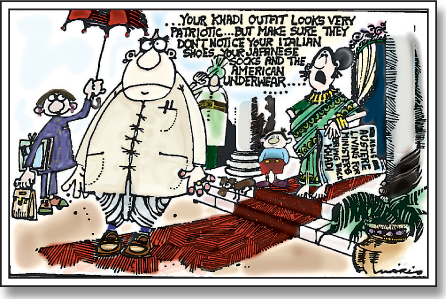

![]() ASHION IN CLOTHING IS A KIND OF LIVING ARCHEOLOGY, a wash-and-wear history. It tells us much about who we are and where we came from, and maybe not a little about where we’re going. Modern clothes tell a story of simple pragmatism. Throughout the world, clothing has become more spartan, more practically polyesterish, less elaborate. Men, especially, have made some dismally utilitarian decisions about their wardrobe. Around 1666 the present-day suit was first stitched in France and England, and by 1872 it was widespread enough in India to be fiercely satirized. Somewhere in that era, men from all cultures made the not-so-natty decision to abandon other attire in favor of the egalitarian grey suit, white shirt and necktie.§

ASHION IN CLOTHING IS A KIND OF LIVING ARCHEOLOGY, a wash-and-wear history. It tells us much about who we are and where we came from, and maybe not a little about where we’re going. Modern clothes tell a story of simple pragmatism. Throughout the world, clothing has become more spartan, more practically polyesterish, less elaborate. Men, especially, have made some dismally utilitarian decisions about their wardrobe. Around 1666 the present-day suit was first stitched in France and England, and by 1872 it was widespread enough in India to be fiercely satirized. Somewhere in that era, men from all cultures made the not-so-natty decision to abandon other attire in favor of the egalitarian grey suit, white shirt and necktie.§

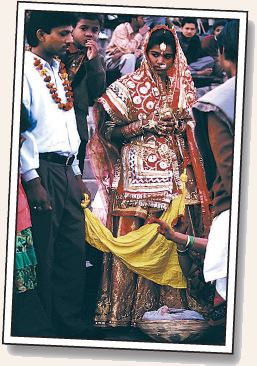

Men around the world lost their national and personal character when they adopted the Western business suit. Japanese men, who once looked so very Nipponese in their graceful robes, now look like Europeans. South Americans, once so distinctive in their hand-woven costumes, now look like the Japanese who look like the Europeans. Indian men, who 200 years ago had regional raiment that was earthy and elaborately colored, now look like the South Americans, who look like the Japanese, who look like the Europeans. Look at the marriage photo to the right. She’s elegant, and he is—there’s a word in the world of fashion—boring!§

A single stretch of fabric that comes in a range of textures and patterns— the sari is creativity at its best.§

I know of what I speak. Visitors to our Hawaiian editorial offices know our monastic staff is not sitting at their MacBook Pros in jeans and T-shirts. We are swathed in saffron and ochre cotton—hand-spun, hand-woven and unsewn—draped in the old South Indian style. I can never forget the first time, three decades ago, that a Jaffna, Sri Lanka, elder helped me wrap a veshti, and then took us to the bustling main market-place. Every step was terrorizing, the unwieldy garment threatening to fall, with me cinching up the subversive sarong several times a minute, both hands never more than a few swift inches from my waist. How awkward I felt, and certainly looked. As time passed and the fabric was tamed, I learned how refined one feels in such attire. It was like floating, living in your spirit more than in your body. To this day, I only feel comfortable and soulful in these traditional robes. Jaffna is, in fact, one of the few sanctuaries where Western pants and shirt are disdained, and most men, including politicians, go around in their veshtis.§

Indian women who wear saris know the sad truth of all this. They have watched their sisters go the way of men, wearing dresses that look like the dresses that every dressmaker dresses her customers in. Okay, women at least have wide options in type and fabric and color. And that is good. But still, women in Japan look like women in Australia, who look like women in China, who all look like women in Europe. There are few kimonos left to announce the passing of a Japanese lady and few ao dai to tell us that the woman shopping over there is Vietnamese.§

So, we pay tribute to India’s women and Hindu women abroad who have not relinquished their elegant dress. They alone have preserved traditional attire, for the sari is the only major apparel to have survived the last 500 years and to remain elegant and voguish daily wear in the 21st century. That’s quite an accomplishment. No wonder the Western world has been smitten by the sari, and every woman with a smidgen of sartorial savvy wants one.§

Exploring the web on saris, I found this gem, written by Shantipriya Kurada in 1994: “The beauty of the sari never ceases to amaze me. There is something strikingly feminine about it. Flowing like sheer poetry, graceful in every contour and fold, it’s a fascinating mixture of tradition and style. A single stretch of fabric that comes in a range of textures and patterns, the sari is creativity at its best. A cotton sari, charmingly simple, starched and perfectly in place, has such a natural feel. Chiffons and crepes add a glamorous touch. Fragile, utterly soft and delicate, they create an aura of fine elegance. Weddings come alive with the grandeur of silk saris. Painstakingly handwoven to the last detail, the brocade created to perfection by skilled hands, each silk sari is a work of art. A sari has such a special place in every girl’s life. It all starts with wrapping around mother’s sari, playfully and clumsily tripping on its edges. Then there is the first sari you wear, perhaps to a college function, looking self-conscious and achingly innocent. And, of course, the precious wedding sari that’s fondly preserved and cherished for a lifetime. In a world of changing fashions, the sari has stood the test of time. There is something almost magical about it, for it continues to symbolize the romantic image of the Indian woman—vulnerable, elusive and tantalizingly beautiful.”§

Historians say the sari can be traced back more than 5,000 years! Sanskrit literature from the Vedic period insists that pleats be part of every woman’s dress. The pleats, say the texts, must be tucked in at the waist, the front or back, so that the presiding deity, Vayu, the God of wind, can whisk away any evil influence that may strike the woman. Colors, too, are ruled by tradition. Yellow, green and red are festive and auspicious, standing for fertility. Red, evoking passion, is a bridal color and part of rituals associated with pregnancy. Blue evokes the life-giving force of the monsoon. Pale cream is soothing and represents bridal purity. A married Hindu woman will not wear a completely white sari, which is reserved for brahmacharinis and widows. §

The sari culturally links the women of India. Whether they are wealthy or poor, svelte or plump, the sari gives them a shared experience, a way in which they are all sisters, forging a link that binds them across all borders, even geographical ones. Women wearing saris in Durban, Delhi or Detroit are part of a social oneness that is nearly eternal and which may, it seems, last yet another thousand years. Jai Hindu women!§

How I Came to Be the “Lady in the Sari”

_________________________§

My personal path of fashion self-discovery took me back to our unbeatable Indian dress§

_________________________§

BY KAVITA DASWANI§

![]() AST YEAR, I HAD TO MAKE A WORK RELATED TRIP TO the Italian city of Vicenza. There I was introduced to an elderly gentleman. “Ah,” he said, clasping my hand. “You have been described to me as the lady in the sari. Why are you not wearing one?” In my functional beige pantsuit, I suddenly felt slightly ashamed. I had gotten off a plane to come straight to the meeting. I didn’t think a sari would be appropriate. This man’s perception was not misplaced. Over the past few years, I have made numerous trips to Europe and the US in my capacity as a fashion writer. When I was much younger, I thought the way to shine was to wear a little black designer dress, like all fashionable women. Then I realized that I had adopted an urban uniform that wasn’t really mine. §

AST YEAR, I HAD TO MAKE A WORK RELATED TRIP TO the Italian city of Vicenza. There I was introduced to an elderly gentleman. “Ah,” he said, clasping my hand. “You have been described to me as the lady in the sari. Why are you not wearing one?” In my functional beige pantsuit, I suddenly felt slightly ashamed. I had gotten off a plane to come straight to the meeting. I didn’t think a sari would be appropriate. This man’s perception was not misplaced. Over the past few years, I have made numerous trips to Europe and the US in my capacity as a fashion writer. When I was much younger, I thought the way to shine was to wear a little black designer dress, like all fashionable women. Then I realized that I had adopted an urban uniform that wasn’t really mine. §

So I learned how to drape a sari. As a Hindu Sindhi girl brought up in the bosom of a semi-traditional trading family in Hong Kong, this sari business should have come naturally. But it didn’t. I was cajoled into wearing one during family weddings after relatives insisted it would “look nice.” But I would stand, frustrated and impatient, while someone would tie and pleat and fold the fabric on me. Then, I carried the sari like a burden.§

Now, my sari-wearing has become a burden no more. Instead, it is an honor and a privilege. Who needs a Chanel gown or a Gucci evening suit—all essentially redolent of sameness—when you can be swathed in a beautiful pink brocade sari, shot with golden threads, its pallu revealing a parade of peacock motifs? What can possibly rival the elegance of a Kanchipuram sari, all handwoven silken threads and flecks of gold? §

So now, whenever I travel, I pack a tiny bag filled with a few saris, some glass bangles, bindis and a shimmering kundan set. At formal dinners in glamorous Western capitals, where low-cut dresses and fanciful frocks are the norm, the effects of me and my sari are fascinating. There is an immediate sense of respect. I am often greeted by a halting “Namaste” instead of a two-cheek Euro-style kiss. People suddenly, surprisingly, become rather tender. §

At an outdoor cafe in Florence once, in a chiffon sari with a colorful tie-dye pattern, I walked past French fashion designer Christian Lacroix. He stopped his conversation to stare at every fold in the fabric and thread. Wanda Ferragamo, owner of the Italian fashion empire that bears her name, made her way across two gilded salons to tell me that I was “the most elegant woman in the room.” At another party in Paris, actress Tracy Ulman peered at my bindi, cast her eyes over my rich ivory silk and gold sari and asked, “Are you someone rich and famous I should know about?” And, most memorably, at a charity benefit in Los Angeles last summer, where Hollywood celebrities competed with one another in their sexy, revealing dresses, I stood apart in a pink and green silk brocade sari. A young American man approached me, looked at the bikini-clad dancers on high platforms around him, pointed at my sari and said, “Now that is how all women should be dressed. I think the sari is God’s gift to womanhood.”§

So the next time I saw the man in Vicenza, I did not disappoint him and arrived in a dark-hued cotton sari. The look of appreciation on his face was worth more than all the designer dresses in the world. §

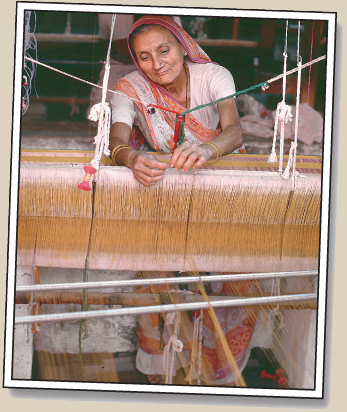

A timeless art: The contemplative craft of weaving§