![]()

Sari’s Unlikely Savior

_________________________

How a French anthropologist, happening upon an unusual sari, rescued dozens of Indian drapes from extinction

_________________________

ELIZABETH PATRICK

Job well done: The exhibition team poses at the end of opening day. Guest curator Chantal Boulanger is in center. Student curator Susheela Hoeffer stands third from left, exhibit designer Jean Ross second from left and Hazel Lutz is second from right.

BY SHIKHA MALAVIYA, MINNESOTA

![]() T IS A BLUSTERY, COLD AFTERNOON AS I MAKE MY WAY TO the Goldstein Gallery and the University of Minnesota’s School of Apparel and Design. Opening the auditorium door, I make out the silhouettes of roughly 200 people focused on a slide of a Tamil woman whose sari wraps around her knees and divides in the middle, a common style among rural working women. The lights turn on, and in the front of the auditorium a petite, blond-haired woman dressed in a navy blue silk sari deftly demonstrates that very style from the slide on a volunteer while explaining its method in a lilting French accent. The audience stares in awe as anthropologist Chantal Boulanger proceeds to unravel the mysteries of sari draping.

T IS A BLUSTERY, COLD AFTERNOON AS I MAKE MY WAY TO the Goldstein Gallery and the University of Minnesota’s School of Apparel and Design. Opening the auditorium door, I make out the silhouettes of roughly 200 people focused on a slide of a Tamil woman whose sari wraps around her knees and divides in the middle, a common style among rural working women. The lights turn on, and in the front of the auditorium a petite, blond-haired woman dressed in a navy blue silk sari deftly demonstrates that very style from the slide on a volunteer while explaining its method in a lilting French accent. The audience stares in awe as anthropologist Chantal Boulanger proceeds to unravel the mysteries of sari draping.

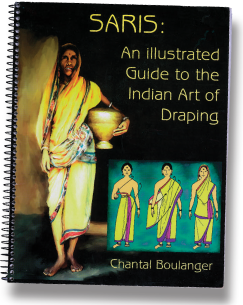

The sari, a versatile female garment of ancient Indian origin, has enthralled and mystified many in its variety of texture, design, size and draping style. While numerous scholars document the intricacies of the sari’s myriad colors, fabrics and patterns, few, if any, have closely examined draping styles. Chantal Boulanger hopes to change that. Boulanger is the author of Saris: An Illustrated Guide to the Indian Art of Draping. In her book, Chantal documents and lucidly illustrates more than 100 sari drapes, which she divides loosely into families and sub-families where possible, based on certain basic draping techniques. By doing so, Boulanger is the first scholar to define the art of sari draping and give its study a legitimacy that goes beyond mere fashion.

Boulanger’s book came to life in an exhibition presented by the University of Minnesota’s Goldstein Gallery January 25–March 1, 1998, aptly called “The Indian Sari: Draping Bodies, Revealing Lives.” It was the first sari exhibition to accentuate draping techniques rather than fabric texture or design aspects.

For Chantal, it all began in 1992 when a unique sari drape at a wedding in South India sparked her interest. “I saw a drape with pleats on the side and its border in the back. I asked how to do it, but no one knew.” Having studied Tamil temple priests for the past fifteen years, Chantal encountered various sari drapes in her field work, but never imagined they would one day become the object of her study. A trip to a research center in Pondicherry turned up little information on the “wedding sari” drape, and her inquiries to Tamil women followed suit. Finally, an old woman identified the mystery sari as a drape worn by peasant women from the region of Tondaimandalamam, in Tamil Nadu. Many young women no longer wore such styles because they didn’t want to be identified as a peasant or a lower caste. Chantal realized that many of these drapes—at times intricate, functional, and in most cases symbolic of religion and social status—carried a certain part of Indian women’s history, and that it would vanish without a trace if not recorded soon.

Zigzagging across the Indian states of Tamil Nadu, Kerala, Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh, Orissa and West Bengal from 1990 to 1997, Chantal visited big cities and remote villages. Taking notes and photos of diverse sari drapes was a constant ritual, even if it meant stopping women on the street. But this wasn’t enough to cognize intricacies of the wrapping art. “I realized the only way to remember these saris was to try them again and again,” Chantal shared with Hinduism Today in 1998. She practiced until she got them right, and wore saris under every possible circumstance to personally experience how saris work in daily life. “Whenever Indian women taught me how to wear a sari, they missed essential steps I had to discover on my own.” Secrets such as knotting a sari instead of just tucking it into a petticoat came with trial and error. Now a bona fide expert in more than eighty drapes, Boulanger is an inspiration to most of us Hindu women who barely know a handful.

A “how-to” book on draping: All the studies on Indian clothing, Chantal points out, have ignored “the extraordinary precision and care that have been devoted to draping in its many forms.” Her book, self-illustrated, shows step-by-step instructions on how to master over 80 drapes.

Dissection: As Chantal organized her information, she realized that most sari drapes could be categorized into families. On grouping various drapes, she found the necessity of a glossary to identify each part of a sari. “Every sari starts with tying it tightly, whether on the waist or chest. So I decided to call it the closing.” Boulanger enlisted words from Sanskrit and Tamil because “I couldn’t just write, ‘tie this end to that end.’” As a result, she terms the part of the sari from which the drape begins, mundi, and the part thrown over the shoulder, pallav. The main part of the sari is the body. The edges are the upper and lower borders.

While Chantal created a working glossary of the sari, she feels most successful in having arranged the sari into families. Studies that preceded her work grouped drapes according to region or state, so she initially followed suit. But as her research progressed, she realized that draping styles cross regions. By focusing on method instead, she found that most sari drapes could fit into four main families [see page 29]. Many drapes overlapped families, indicating migration of a group from one region to another—and some saris were unique and did not fit within any family—but the grouping of saris revealed many things. “I saw dhoti styles worn mainly by the brahmins,” shares Boulanger, “while veshti-style drapes appeared on other classes.” In this context, Boulanger applauds the modern nivi drape, with its pleats in front and pallav over the left shoulder, calling it the egalitarian sari because, she enthuses, “It crosses boundaries of class and caste, making all women equal in the eyes of others.”

Charmed by the sari’s visual appeal and social context, Chantal dreamed of a sari exhibition. But as she pitched the idea to friends and colleagues, they urged her to write a book to supplement it. Accepting the suggestion, Chantal labored five years and finished the project in 1997. Her biggest challenge was creating more than 700 illustrations which she personally drew and redrew until satisfied they were clear and accurate. The exhibition of Boulanger’s work would marry the aesthetic importance of drapes with related cultural implications.

The Full Six Yards

Feminine, graceful, elegant are a few words that come to mind when you hear the word sari. The modern sari has stepped beyond tradition to become a fashion statement. Designer saris, and blouses too, have made their mark beyond India’s borders, draped in ways that seem very fashionable but are actually like how they were worn very long ago in India. The six yards has come a full circle, it appears. ¶For many women, their very first attempt to wear a sari would have been when they were five or six years old. You guessed it! They want to be like their mother. Imagine wrapping a full length sari around that tiny body! As she grows, the little girl gets other inputs, and these days more often than not, the sari is looked down upon as “not in.” College is the time when the sari regains its stature on special occasions, especially weddings. Grandparents fawning over their “little big lady” is a sweet moment to witness. ¶Many city girls grow up never having worn a sari. So much material going around (God knows how!) in hot weather. The pallu slipping off, the waist being visible, stepping on the pleats and having the sari come off are but a few mini-nightmares she would have to overcome before gaining the courage to make the first attempt. Once bitten, totally smitten is usually what happens. Rarely does someone say, “Not for me.” The magic of the sari begins to work! The way one feels in a sari can only be experienced. It cannot be described. Try it. You will like it!

Sheela Venkatakrishnan, Chennai

Drape display: The Goldstein exhibit rendered sari draping with such authenticity that it provoked visitors to feel transported to India. Call it coincidence or kismet that student curators Hazel Lutz and Susheela Hoeffer had both sojourned in India, and Jean Ross, responsible for exhibit design, had visited India and Pakistan. Lutz and Hoeffer primarily focused on drape families and technique, but also featured saris in various contexts, such as photographs, a wall of artwork (including a sketch by world-renowned artist Jamini Roy), a display of blouse styles, Indian dolls dressed in saris, and hanging saris as well, because as Hoeffer observed, “It’s hard to visualize the mass of a sari as a flat piece of cloth when it is draped on the body.”

Lutz (who co-authored The Visible Self: Global Perspectives on Dress, Culture, and Society), saw the exhibition as a way to “fully appreciate the complexity of drapes, and drop stereotypes. We are showing that there is innovation within the confines of a sari, and tradition is fashionable as well as practical.” Ross added a rural touch to the exhibition by painting the walls saffron and the top with a red, stenciled border, reminiscent of villages in India and Pakistan. With Boulanger’s work as their focus, and their individual experiences in India to draw from, Lutz, Hoeffer and Ross turned an intimate gallery into a colorful Indian oasis of art and savoir-faire.

The exhibition drew over 200 on opening day, some out of curiosity, others to learn. Regardless of motives, visitors left the exhibit with fresh knowledge. As Mani Subramaniam, native of India and business professor at the University of Minnesota’s Carlson School of Management commented, “On my next visit to India, I’ll definitely be looking at saris more carefully, even though I have seen them all my life.” A fitting compliment for Chantal Boulanger and her work, and for women worldwide who make the sari an integral part of their lives.

Chantal Boulanger Publishing website: www.devi.net