Heralding the Drapes of India

_________________________§

Excerpts from Chantal’s book, one woman’s fashion odyssey§

_________________________§

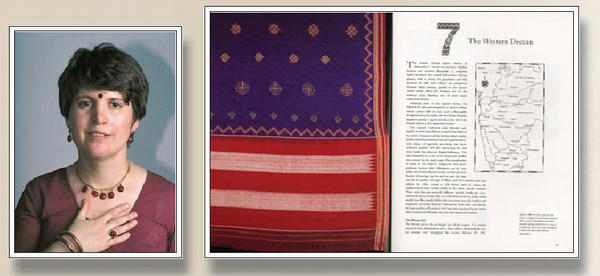

Anthropological modeling: Chantal wore them all§

BY CHANTAL BOULANGER§

![]() F ALL THE ARTS THAT HAVE FLOURISHED IN INDIA, one of the least known and studied is that of draping. This is all the more extraordinary because it is a unique art and craft which offers special insights into the ethnology of Indian and Southeast Asian peoples and the archaeology of the periods in which it developed. At its heart is Hinduism, whose preference for unstitched clothing, for both religious and social reasons, fostered the growth and development of the sari. Although knowledge of sewn garments has existed since prehistoric times, these were mostly reserved for warriors and kings, and never achieved the popularity of drapes. Therefore, the Indian culture developed the art of wrapping a piece of cloth around the body to a degree that far surpassed that of any other people. Unfortunately, this art has never been fully studied. Books on saris usually show a maximum of 10 or 15 drapes, and too few explain how to drape them. Most of these studies have been done by men who have never experimented with the drapes themselves. §

F ALL THE ARTS THAT HAVE FLOURISHED IN INDIA, one of the least known and studied is that of draping. This is all the more extraordinary because it is a unique art and craft which offers special insights into the ethnology of Indian and Southeast Asian peoples and the archaeology of the periods in which it developed. At its heart is Hinduism, whose preference for unstitched clothing, for both religious and social reasons, fostered the growth and development of the sari. Although knowledge of sewn garments has existed since prehistoric times, these were mostly reserved for warriors and kings, and never achieved the popularity of drapes. Therefore, the Indian culture developed the art of wrapping a piece of cloth around the body to a degree that far surpassed that of any other people. Unfortunately, this art has never been fully studied. Books on saris usually show a maximum of 10 or 15 drapes, and too few explain how to drape them. Most of these studies have been done by men who have never experimented with the drapes themselves. §

When I was studying Tamil temple priests, I learned that the women draped their saris in a special way, using a piece of cloth nine yards long. It is a well-known fact that Tamil brahmins, such as the Coorg, Bengali or Marwari women, have their own peculiar way of wearing saris. Yet, nobody had noticed the way Tamil peasant or Kannadiga laborers draped theirs—and neither had I. §

Having discovered that sari draping had never been properly researched, I decided to record as many drapes as I could find. As I traveled throughout South, Central and Eastern India, I realized that the whole subject was far too big for my own researches to be exhaustive. I hope, however, that this work will lead others to carry on this research all over India. Apart from the few famous saris recorded in the past, I found a large number of drapes, most often typical of a caste or a small region. Only worn by old women, the majority of them will be forgotten in a few decades. §

The modern drape, often called nivi sari, is now worn by most Indian women. Few even bother to learn from their grandmothers how to attire themselves traditionally. This is especially true with the lower castes, where girls refuse to dress in a way that clearly displays their humble origins. §

“Show me how you drape, and I will tell you who you are” could be the motto for this book. Drapes are closely linked with the ethnic origin of the wearer, and in Chapter Seven I detail the conclusions that I reached from this study. §

I started this research totally unaware of its wide implications (not to mention the time and effort!). Thinking that I would save a few drapes from fast-approaching oblivion, I discovered a totally unexplored world whose meaning had never been considered. §

Researching drapes requires travelling through as many villages and regions as possible, looking at everybody to identify precisely what they wear, and asking everyone if they know or have seen different ways of draping. Once I found an unknown drape, I not only saw how it was produced from the person who usually wore it, but I also learned how to do it myself. It was very important for me to be able to wear it. Since this might seem a little extreme, here is an anecdote which will illustrate the necessity. §

I always thought I knew how to wear a kaccha sari, such as worn in North Karnataka and Maharashtra. All I had to do was to drape a modern sari with nine yards, so as to have many pleats in front. Then I had to take the lower border of the middle pleat and tuck it in the back. When I went to the region where these saris were worn, I did not bother at first to learn how to drape them. Problems started when I decided to go out wearing a kaccha sari. It was in Goa and I went to a Hindu temple, where I was clearly conspicuous. Most people appreciated my efforts, but at one point, a woman, seeing me, shouted something in Konkani and everybody laughed. My assistant was reluctant to translate, but eventually he explained that the woman had said: “The way she wears her sari, all the boys are going to fall in love with her!” §

I understood that something was wrong with my draping and immediately I sent my assistant to find someone who could teach me how to wear it properly. A few minutes later, a woman showed me many of the finer details which prevent this kind of drape from crumpling up and backwards, revealing the thighs. §

I have travelled quite extensively through Tamil Nadu, Kerala, Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka. I have also visited Goa, Maharashtra, Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh, Orissa and West Bengal, although not as thoroughly. A short trip in Assam convinced me that there is much to learn in this area. Exhaustive research would have meant visiting almost every village and caste in India, a task far too difficult for me. This may again sound a little extreme, but many drapes are worn by small castes, and may only be found in a village or two. For instance, the Kappulu sari, one of the most interesting and elegant drapes I have found, is worn only by old women of the Kappulu caste.§

I have asked many women to teach me how to drape their saris. Most of them were unknown to me, and I had simply met them in the street. None refused and every one of them, from the educated Brahmin to the illiterate tribeswoman, understood what I was doing and why. They were all pleased with my work and entrusted to me their knowledge with pride.§

The woman who taught me the pullaiyar sari was about four feet tall, and so old that no one in the village knew her age. She was illiterate and spoke a dialect of Tamil I hardly understood. But I could see she was happy to give me what she clearly perceived as part of her culture and identity. When I left she took my hand and said, “Go and tell others who we are.” From her village, I walked several miles through the jungle to the nearest road and eventually came back to France, keeping the photograph I had taken of her as a treasure. §

Styles, Patterns, History & Techniques

(from right) The cover of the book; a sample spread, focusing on the Western Deccan; the author, Linda Lynton§

![]() INDA LYNTON-SINGH, A PROFESSIONAL WRITER, BECAME CURIOUS ABOUT SARIS when, upon marrying Sanjay Singh, a native of India, she was welcomed by his extended family with gifts of saris. “I heard stories about local saris and hoped to find more stories about saris from other regions of India, so I looked for books, but didn’t find many,” Linda recalls. That lack of information on saris inspired five years of research and an expansive tome—The Sari: Styles, Patterns, History, Techniques. By concentrating on region, Linda captures the sari’s beauty and complexity in vivid detail through ethnic art, historical facts, motifs and patterns, all which integrate and represent their geographical surroundings. “Most of the world uses tailored clothing, and here is a culture that doesn’t,” explains Linda. “The whole emphasis is on the cloth itself, how it’s woven, how it’s decorated, how it’s colored, and that alone makes it interesting.” Particularly notable in the book are textiles from groups, such as Gujarati indigo-dyed saris that heretofore were never illustrated and documented. While Chantal Boulanger’s book is a practical manual on draping techniques, Linda surveys the sari as a prized fabric, focusing on its design. From this perspective, Linda documents forty types of saris with photographs and diagrams to illustrate complexity in patterns, weaves and colors. She also includes a comprehensive glossary of textile terms, in English and Indian languages. An exhaustive and scholarly work, 208 pages, with photographs by her husband, Sanjay K. Singh. §

INDA LYNTON-SINGH, A PROFESSIONAL WRITER, BECAME CURIOUS ABOUT SARIS when, upon marrying Sanjay Singh, a native of India, she was welcomed by his extended family with gifts of saris. “I heard stories about local saris and hoped to find more stories about saris from other regions of India, so I looked for books, but didn’t find many,” Linda recalls. That lack of information on saris inspired five years of research and an expansive tome—The Sari: Styles, Patterns, History, Techniques. By concentrating on region, Linda captures the sari’s beauty and complexity in vivid detail through ethnic art, historical facts, motifs and patterns, all which integrate and represent their geographical surroundings. “Most of the world uses tailored clothing, and here is a culture that doesn’t,” explains Linda. “The whole emphasis is on the cloth itself, how it’s woven, how it’s decorated, how it’s colored, and that alone makes it interesting.” Particularly notable in the book are textiles from groups, such as Gujarati indigo-dyed saris that heretofore were never illustrated and documented. While Chantal Boulanger’s book is a practical manual on draping techniques, Linda surveys the sari as a prized fabric, focusing on its design. From this perspective, Linda documents forty types of saris with photographs and diagrams to illustrate complexity in patterns, weaves and colors. She also includes a comprehensive glossary of textile terms, in English and Indian languages. An exhaustive and scholarly work, 208 pages, with photographs by her husband, Sanjay K. Singh. §

COURTESY LINDA LYNTON§

Sources: To help complete my field research, I used information provided by other scholars in books or orally. For antique drapes, the work of Anne-Marie Loth, La vie publique et privee dans l’Inde ancienne, fascicule VII, les costumes (1979), is the most detailed and complete book available on draping. For Bihar, Uttar Pradesh and Nepal, I relied on information from Linda Lynton-Singh [see her book below], who is a textile specialist and who had learned several drapes from Northeast India (her husband is from Bihar). Thambal Yaima showed me the two styles draped in Manipur. Mrs. Ruklanthi Jayatissa helped me with the saris worn in Sri Lanka. For Madhya Pradesh, I also studied very closely the book Saris of India: Madhya Pradesh, by Chishti and Samyal (1989). I tried all the drapes myself. For tribal saris, I relied on the book The Tribals of India through the Lens of Sunil Janah (1993). §

I don’t believe that these drapes should simply be recorded and then confined to dusty libraries in the future. Drapes have many advantages over stitched clothes, especially when beauty is an important value. Saris are much more practical than we think, especially since they can be so easily modified. I made this work for anybody who wants, at least once, to wear a drape, any kind of drape. Draping is an art. I hope this book will help it take its place as a heritage of mankind.§

Chantal died suddenly in Africa of a brain aneurism on December 27, 2004, the day after the Asian Tsunami. She was cremated in London, and her ashes were spread by her husband Peter Maloney on the shore at Mahabalipuram in Tamil Nadu, India. §