THE THIRD OBSERVANCE

Giving

Dāna दान

IVING, DĀNA, IS THE THIRD GREAT RELIGIOUS PRACTICE, OR NIYAMA. IT IS IMPORTANT TO REMEMBER THAT GIVING FREELY OF ONE’S GOODS IN FULFILLING NEEDS, MAKING SOMEone happy or putting a smile on his face, mitigates selfishness, greed, avarice and hoarding. But the most important factor is “without thought of reward.” The reward of joy and the fullness you feel is immediate as the gift passes from your two hands into the outstretched hands of the receiver. Dāna is often translated as “charity.” But charity in modern context is a special kind of giving by those who have to those who have not. This is not the true spirit of dāna. The word fulfillment might describe dāna better. The fulfillment of giving that wells up within the giver as the gift is being prepared and as the gift is being presented and released, the fulfillment of the expectancy of the receiver or the surprise of the receiver, and the fullness that exists afterwards are all a part of dāna.§

IVING, DĀNA, IS THE THIRD GREAT RELIGIOUS PRACTICE, OR NIYAMA. IT IS IMPORTANT TO REMEMBER THAT GIVING FREELY OF ONE’S GOODS IN FULFILLING NEEDS, MAKING SOMEone happy or putting a smile on his face, mitigates selfishness, greed, avarice and hoarding. But the most important factor is “without thought of reward.” The reward of joy and the fullness you feel is immediate as the gift passes from your two hands into the outstretched hands of the receiver. Dāna is often translated as “charity.” But charity in modern context is a special kind of giving by those who have to those who have not. This is not the true spirit of dāna. The word fulfillment might describe dāna better. The fulfillment of giving that wells up within the giver as the gift is being prepared and as the gift is being presented and released, the fulfillment of the expectancy of the receiver or the surprise of the receiver, and the fullness that exists afterwards are all a part of dāna.§

Daśamāṁśa, tithing, too, is a worthy form of dāna—giving God’s money to a religious institution to fulfill with it God’s work. One who is really fulfilling dāna gives daśamāṁśa, never goes to visit a friend or relative with empty hands, gives freely to relatives, children, friends, neighbors and business associates, all without thought of reward. The devotee who practices dāna knows fully that “you cannot give anything away.” The law of karma will return it to you full measure at an appropriate and most needed time. The freer the gift is given, the faster it will return.§

What is the proportionate giving after daśamāṁśa, ten percent, has been deducted. It would be another two to five percent of one’s gross income, which would be equally divided between cash and kind if someone wanted to discipline his dāna to that extent. That would be fifteen percent, approximately one sixth, which is the makimai established in South India by the Chettiar community around the Palani Temple and now practiced by the Malaka Chettiars of Malaysia.§

If one were to take a hard look at the true spirit of dāna in today’s society, the rich giving to religious institutions for a tax deduction are certainly giving with a thought of reward. Therefore, giving after the tax deductions are received and with no material benefits or rewards of any kind other than the fulfillment of giving is considered by the wise to be a true expression of dāna. Making something with one’s own hands, giving in kind, is also a true expression of dāna. Giving a gift begrudgingly in return for another gift is, of course, mere barter. Many families barter their way through life in this way, thinking they are giving. But such gifts are cold, the fulfillment is empty, and the law of karma pays discounted returns.§

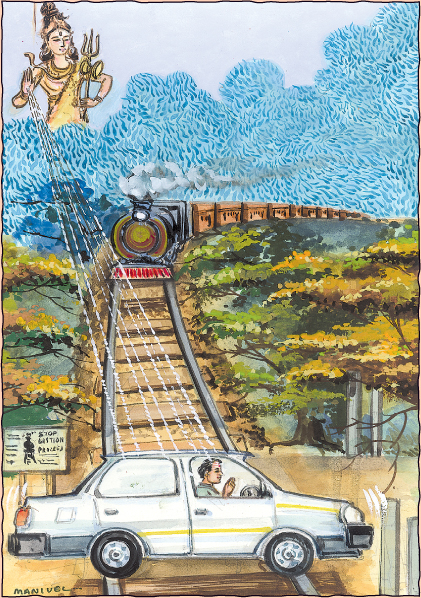

Hospitality and Fullness§

Hospitality is a vital part of fulfilling dāna. When guests come, they must be given hospitality, at least a mat to sit on and a glass of water to drink. These are obligatory gifts. You must never leave your guest standing, and you must never leave your guest thirsty. If a guest were to smell even one whiff from the kitchen of the scented curries of a meal being prepared, he must be asked four times to stay for the meal. He will politely refuse three times and accept on the fourth invitation. This is also an obligatory giving, for the guest is treated as God. God Śiva’s veiling grace hides Śiva as He dresses in many costumes. He is a dancer, you know, and dancers wear many costumes. He will come as a guest to your home, unrecognizable. You might think it is your dear friend from a far-off place. That, too, is Śiva in another costume, and you must treat that guest as Śiva. Giving to Śiva Śiva’s own creation in your mind brings the highest rewards through the law of karma.§

Even if you think you are giving creatively, generously, looking for no rewards, but you are giving for a purpose, that karma will still pay you back with full interest and dividends. This is a positive use of the law of karma. It pays higher interest than any bank. This is not a selfish form of giving. It is the giving of the wise, because you know the law of karma, because you know the Sanātana Dharma—the divine, eternal laws. If you see a need that you can fill and have the impulse to give but recoil from giving, later, when you are in need, there will be someone who has the impulse to give to you but will recoil from giving. The wheels of karma grind slowly but exceedingly well the grains of actions, be they in thought, emotion or those of a physical nature. So, one can be quite selfish and greedy about wanting to practice dāna to accumulate the puṇya for the balance of this life, the life in-between lives, in the astral world, and for a good birth in the next incarnation. The practice of dāna is an investment in a better life, an investment that pays great dividends.§

We are not limited by our poverty or wealth in practicing giving. No matter how poor you are, you can still practice it. You can give according to your means, your inspiration, your ability. When the fullness has reached its peak within you while preparing the gift, be it arranging a bouquet of freshly picked flowers, a tray of fruit, counting out coins, sorting a pile of bills or putting zeros on a check that you’re writing, then you know that the gift is within your means. Gifts within your means and from your heart are the proper gifts.§

The Selfish and Miserly§

The virtue of dāna deals with the pragmatic physical transference of cash or kind. It is the foundation and the life blood of any other form of religious giving, such as giving of one’s time. Many people rationalize, “I’ll give my time to the temple. I’ll wash the pots, scrub the floor and tidy up. But I can’t afford to give of my limited wealth proportionate to what would be total fulfillment of giving.” Basically, they have nothing better to do with their time, and to ease their own conscience, they volunteer a little work. There is no merit, no puṇya, in this, only demerit, pāpa. No, it’s just the other way around. One who has perfected dāna in cash and in kind and is satisfied within this practice, this niyama, will then be able and willing to give of his time, to tithe ten percent of his time, and then give time over and above that to religious and other worthy causes. Shall we say that the perfection of dāna precedes seva, service?§

What can be said of someone who is all wrapped up in his personal self: concealing his personal ego with a pleasant smile, gentle deeds, soft words, but who just takes care of “number one”? For instance, if living with ten people, he will cook for himself and not cook for the others. He gets situations confused, entertains mental arguments within himself and is always worried about the progress in his religious life. We would say he is still trying to work on the restraints—compassion, patience, sexual purity, moderate appetite—and has not yet arrived at number three on the chart of the practices called niyamas. Modern psychology would categorize him as self-centered, selfish, egotistical. To overcome this selfishness, assuming he gets the restraints in order, doing things for others would be the practice, seeing that everyone is fed first before he eats, helping out in every way he can, performing anonymous acts of kindness at every opportunity.§

In an orthodox Hindu home, the traditional wife will follow the practice of arising in the morning before her husband, preparing his hot meal, serving him and eating only after he is finished; preparing his lunch, serving him and eating after he is finished; preparing his dinner, serving him and eating after he is finished, even if he returns home late. Giving to her husband is her fulfillment, three times a day. This is built into Hindu society, into Śaivite culture.§

Wives should be allowed by their husbands to perform giving outside the home, too, but many are not. All too often, they are held down, embarrassed and treated almost like domestic slaves—given no money, given no things to give, disallowed to practice dāna, to tithe and give creatively without thought of reward. Such domineering, miserly and ignorant males will get their just due in the courts of karma at the moment of death and shortly after. The divine law is that the wife’s śakti power, once released, makes her husband magnetic and successful in his worldly affairs, and their wealth accumulates. He knows from tradition that to release this śakti he must always fulfill all of the needs of his beloved wife and give her generously everything she wants.§

Many Ways of Giving§

There are so many ways of giving. Arising before the Sun comes up, greeting and giving namaskāra to the Sun is a part of Śaivite culture. Dāna is built into all aspects of Hindu life—giving to the holy man, giving to the astrologer, giving to the teacher, giving dakshiṇā to a swāmī or a satguru for his support, over and above all giving to his institution, over and above daśamāṁśa, over and above giving to the temple. If the satguru has satisfied you with the fullness of his presence, you must satisfy yourself in equal fullness in giving back. You can be happily fat as these two fullnesses merge within you. By giving to the satguru, you give him the satisfaction of giving to another, for he has no needs except the need to practice dāna.§

Great souls have always taught that, among all the forms of giving, imparting the spiritual teachings is the highest. You can give money or food and provide for the physical aspects of the being, but if you can find a way to give the dharma, the illumined wisdom of the traditions of the Sanātana Dharma, then you are giving to the spirit of the person, to the soul. Many Hindus buy religious literature to give away, because jñāna dāna, giving wisdom, is the highest giving. Several groups in Malaysia and Mauritius gave away over 70,000 pieces of literature in a twenty-month period. Another group in the United States gave away 300,000 pieces of literature in the same period. Many pieces of that literature changed the lives of individuals and brought them into a great fullness of soul satisfaction. An electric-shock blessing would go out from them at the peak of their fulfillment and fill the hearts of all the givers. Giving through education is a glorious fulfillment for the giver, as well as for the receiver.§

Wealthy men in India will feed twenty thousand people in the hopes that one enlightened soul who was truly hungry at that time might partake of this dāna and the śakti that arises within him at the peak of his satisfaction will prepare for the giver a better birth in his next life. This is the great spirit of anna yajñā, feeding the masses.§

Along with the gift comes a portion of the karma of the giver. There was an astrologer who when given more than his due for a jyotisha consultation would always give the excess to a nearby temple, as he did not want to assume any additional karma by receiving more than the worth of his predictions. Another wise person said, “I don’t do the antyeshṭi saṁskāra, funeral rites, because I can’t receive the dāna coming from that source of sadness. It would affect my family.” Giving is also a way of balancing karma, of expressing gratitude for blessings received. A devotee explained, “I cannot leave the temple without giving to the huṇḍi, offering box, according to the fullness I have received as fullness from the temple.” A gourmet once said, “I cannot leave the restaurant until I give gratuity to the waiter equaling the satisfaction I felt from the service he gave.” This is dāna, this is giving, in a different form.§

Children should be taught giving at a very young age. They don’t yet have the ten restraints, the yamas, to worry about. They have not been corrupted by the impact of their own prārabdha karmas. Little children, even babies, can be taught dāna—giving to the temple, to holy ones, to one another, to their parents. They can be taught worship, recitation and, of course, contentment—told how beautiful they are when they are quiet and experiencing the joy of serenity. Institutions should also give, according to their means, to other institutions.§

How Monks Fulfill Dāna§

It is very important for sādhus, sannyāsins, swāmīs, sādhakas, any mendicant under vows, to perform dāna. True, they are giving all of their time, but that is fulfillment of their vrata. True, they are not giving daśamāṁśa, because they are not employed and have no income. For them, dāna is giving the unexpected in unexpected ways—serving tea for seven days to the tyrannical sādhu that assisted them by causing an attack of āṇava, of personal ego, within them, in thanks to him for being the channel of their prārabdha karmas and helping them in the next step of their spiritual unfoldment. Dāna is making an unexpected wreath of sacred leaves and flowers for one’s guru and giving it at an unexpected time. Dāna is cooking for the entire group and not just for a few or for oneself alone.§

When one has reached an advanced stage on the spiritual path, in order to go further, the law requires giving back what one has been given. Hearing oneself speak the divine teachings and being uplifted and fulfilled by filling up and uplifting others allows the budding adept to go through the next portal. Those who have no desire to counsel others, teach or pass on what they have learned are still in the learning stages themselves, traumatically dealing with one or more of the restraints and practices. The passing on of jñāna, wisdom, through counseling, consoling, teaching Sanātana Dharma and the only one final conclusion, monistic Śaiva Siddhānta, Advaita Īśvaravāda, is a fulfillment and completion of the cycle of learning for every monastic. This does not mean that he mouths indiscriminately what he has been told and memorized, but rather that he uses his philosophical knowledge in a timely way according the immediate needs of the listener, for wisdom is the timely application of knowledge.§

The dāna sādhana, of course, for sādhakas, sādhus, yogīs and swāmīs, as they have no cash, is to practice dāna in kind, physical doing, until they are finally able to release the Sanātana Dharma from their own lips, as a natural outgrowth of their spirituality, spirit, śakti, bolt-of-lightening outpouring, because they are so filled up. Those who are filled up with the divine truths, in whom when that fullness is pressed down, compacted, locked in, it still oozes out and runs over, are those who pass on the Sanātana Dharma. They are the catalysts not only of this adult generation, but the one before it still living, and of children and the generations yet to come.§