THE FIRST RESTRAINT

Noninjury

Ahiṁsā अहिंसा

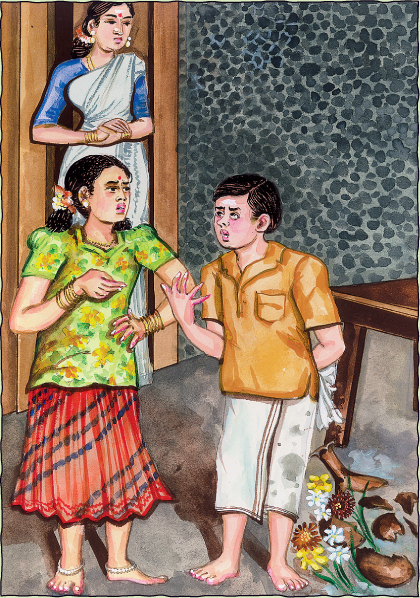

HE FIRST YAMA IS AHIṀSĀ, NONINJURY. TO PRACTICE AHIṀSĀ, ONE HAS TO PRACTICE SANTOSHA, CONTENTMENT. THE SĀDHANA IS TO SEEK JOY AND SERENITY IN LIFE, REmaining content with what one has, knows, is doing and those with whom he associates. Bear your karma cheerfully. Live within your situation contentedly. Hiṁsā, or injury, and the desire to harm, comes from discontent.§

HE FIRST YAMA IS AHIṀSĀ, NONINJURY. TO PRACTICE AHIṀSĀ, ONE HAS TO PRACTICE SANTOSHA, CONTENTMENT. THE SĀDHANA IS TO SEEK JOY AND SERENITY IN LIFE, REmaining content with what one has, knows, is doing and those with whom he associates. Bear your karma cheerfully. Live within your situation contentedly. Hiṁsā, or injury, and the desire to harm, comes from discontent.§

The ṛishis who revealed the principles of dharma or divine law in Hindu scripture knew full well the potential for human suffering and the path which could avert it. To them a one spiritual power flowed in and through all things in this universe, animate and inanimate, conferring existence by its presence. To them life was a coherent process leading all souls without exception to enlightenment, and no violence could be carried to the higher reaches of that ascent. These ṛishis were mystics whose revelation disclosed a cosmos in which all beings exist in interlaced dependence. The whole is contained in the part, and the part in the whole. Based on this cognition, they taught a philosophy of nondifference of self and other, asserting that in the final analysis we are not separate from the world and its manifest forms, nor from the Divine which shines forth in all things, all beings, all peoples. From this understanding of oneness arose the philosophical basis for the practice of noninjury and Hinduism’s ancient commitment to it.§

We all know that Hindus, who are one-sixth of the human race today, believe in the existence of God everywhere, as an all-pervasive, self-effulgent energy and consciousness. This basic belief creates the attitude of sublime tolerance and acceptance toward others. Even tolerance is insufficient to describe the compassion and reverence the Hindu holds for the intrinsic sacredness within all things. Therefore, the actions of all Hindus are rendered benign, or ahiṁsā. One would not want to hurt something which one revered.§

On the other hand, when the fundamentalists of any religion teach an unrelenting duality based on good and evil, man and nature or God and Devil, this creates friends and enemies. This belief is a sacrilege to Hindus, because they know that the attitudes which are the by-product are totally dualistic, and for good to triumph over that which is alien or evil, it must kill out that which is considered to be evil.§

The Hindu looks at nothing as intrinsically evil. To him the ground is sacred. The sky is sacred. The sun is sacred. His wife is a Goddess. Her husband is a God. Their children are devas. Their home is a shrine. Life is a pilgrimage to mukti, or liberation from rebirth, which once attained is the end to reincarnation in a physical body. When on a holy pilgrimage, one would not want to hurt anyone along the way, knowing full well the experiences on this path are of one’s own creation, though maybe acted out through others.§

Noninjury for Renunciates§

Ahiṁsā is the first and foremost virtue, presiding over truthfulness, nonstealing, sexual purity, patience, steadfastness, compassion, honesty and moderate appetite. The brahmachārī and sannyāsin must take ahiṁsā, noninjury, one step further. He has mutated himself, escalated himself, by stopping the abilities of being able to harm another by thought, word or deed, physically, mentally or emotionally. The one step further is that he must not harm his own self with his own thoughts, his own feelings, his own actions toward his own body, toward his own emotions, toward his own mind. This is very important to remember. And here, at this juncture, ahiṁsā has a tie with satya, truthfulness. The sannyāsin must be totally truthful to himself, to his guru, to the Gods and to Lord Śiva, who resides within him every minute of every hour of every day. But for him to truly know this and express it through his life and be a living religious example of the Sanātana Dharma, all tendencies toward hiṁsā, injuriousness, must always be definitely harnessed in chains of steel. The mystical reason is this. Because of the brahmachārī’s or sannyāsin’s spiritual power, he really has more ability to hurt someone than he or that person may know, and therefore his observance of noninjury is even more vital. Yes, this is true. A brahmachārī or sannyāsin who does not live the highest level of ahiṁsā is not a brahmachārī.§

Words are expressions of thoughts, thoughts created from prāṇa. Words coupled with thoughts backed up by the transmuted prāṇas, or the accumulated bank account of energies held back within the brahmachārī and the sannyāsin, become powerful thoughts, and when expressed through words go deep into the mind, creating impressions, saṁskāras, that last a long time, maybe forever. It is truly unfortunate if a brahmachārī or sannyāsin loses control of himself and betrays ahiṁsā by becoming hiṁsā, an injurious person—unfortunate for those involved, but more unfortunate for himself. When we hurt another, we scar the inside of ourself; we clone the image. The scar would never leave the sannyāsin until it left the person that he hurt. This is because the prāṇas, the transmuted energies, give so much force to the thought. Thus the words penetrate to the very core of the being. Therefore, angry people should get married and should not practice brahmacharya.§