Our Sacred Earth

Mother Earth is suffering so much, I feel so sad. We don’t have reverence for our Mother Earth; that is why in modern times we are mercilessly using all of this modern equipment and chemicals. There is so much pollution. Thought pollution is the worst–so many negative thoughts. When we have the spiritual fl avor in life, we are never going to entertain these negative instincts in the mind. The mind will become so pure because of meditation and true devotion. With that devotion we will become selfl ess, and then Mother Earth will feel comfortable with us in her lap. Our holy rishis give us many remedies, including daily yajna using medicinal plants, which heals nature.

AMMA SRI KARUNAMAYI

EDUCATIONAL INSIGHT

Hinduism and The Environment

By Matthew McDermott

Ishavasyam idam sarvam – “This entire universe is to be looked upon as the Lord.”

Shukla Yajur Veda, Ishavasya Upanishad - 1

The above three words in Sanskrit and eleven in English express the essential Hindu outlook on the world. It is a reverential attitude towards all of life, from the smallest animal and tallest tree, to the longest river and mightiest mountain, and even the stars and planets. Writing in Living with Siva, Sivaya Subramuniyaswami urges: “Let’s worship the Earth. It is a being—intelligent and always giving. Our physical bodies are sustained by her abundance. When her abundance is withdrawn, our physical bodies are no more. The ecology of this planet is an intricate intelligence. Through sacrifice, which results in tapas and sadhana, we nurture Mother Earth’s goodwill, friendliness and sustenance. Instill in yourself appreciation, recognition. We should not take advantage of all this generosity, as a predator does of those he preys upon.” ¶On the Abrahamic view of man and world, Swami Dayananda Saraswati shares, “If one believes that God created the Earth with its flora and fauna for human consumption and pleasure, the attitude cannot be expected to be kind to nature.” ¶A quick glance at the headlines of the science and environment section of any major news outlet in the world today—let alone specialist publications dedicated to covering ecological issues—shows that it is the latter attitude and not the classically expressed Hindu viewpoint that holds sway in the world today, no matter the continent or nation. The Hindu Declaration on Climate Change, presented in December 2009 at the Parliament of the World’s Religions in Australia, expresses clearly the state of affairs: “Our beloved Earth, so touchingly looked upon as the Universal Mother, has nurtured mankind through millions of years of growth and evolution. Now centuries of rapacious exploitation of the planet have caught up with us, and a radical change in our relationship with nature is no longer an option. It is a matter of survival. We cannot continue to destroy nature without also destroying ourselves.” ¶How far we have drifted from the reverential sentiment expressed in “My salutations to you, O Bhudevi, consort of the all-pervasive Lord, forgive me for placing my feet upon you.”

Climate Change in Photos

THOMAS KELLY, PHOTOGRAPHER

Most of the photos in this Insight were taken by Thomas Kelly, a resident of Nepal, as part of project called Climate Change Globally, in which he documented the impact of global warming in Nepal, Mongolia and South America. He writes: “I captured images showing deforestation in the Himalayan regions, major flooding in the southern Nepal belt (ripping apart and silting of agricultural land), the change of bird migration patterns, the permafrost melting in northern parts of Mongolia leading to invasive shrubbery taking over lichen fields (a favorite and essential food for the reindeer), an invasive plant species Mikania micrantha (Michaha Jhar) that is spreading at an alarming rate in Chitwan National Park (strangling indigenous plant and tree life and affecting the eating patterns of the Greater One-Horned Rhino), the aggressive water hyacinth spreading over fishing ponds (impacting fishing patterns), glacial lakes bursting, the drying up of high Himalayan forests (resulting in forest fires), the drying up of water springs needed for drinking (irrigation is also drying up, and the water mills used for grinding wheat have stopped). It’s incredible what a ripple climate change can have. You wouldn’t think builders would be affected, but of course they are. Construction experts say traditional knowledge about how to build houses is dying out. Now homes have thinner walls and the roofs need less support. It just isn’t as cold as it used to be, nor does it snow as much, so we’re forgoing traditional insulation and construction techniques and materials.”

Most of the photos in this Insight were taken by Thomas Kelly, a resident of Nepal, as part of project called Climate Change Globally, in which he documented the impact of global warming in Nepal, Mongolia and South America. He writes: “I captured images showing deforestation in the Himalayan regions, major flooding in the southern Nepal belt (ripping apart and silting of agricultural land), the change of bird migration patterns, the permafrost melting in northern parts of Mongolia leading to invasive shrubbery taking over lichen fields (a favorite and essential food for the reindeer), an invasive plant species Mikania micrantha (Michaha Jhar) that is spreading at an alarming rate in Chitwan National Park (strangling indigenous plant and tree life and affecting the eating patterns of the Greater One-Horned Rhino), the aggressive water hyacinth spreading over fishing ponds (impacting fishing patterns), glacial lakes bursting, the drying up of high Himalayan forests (resulting in forest fires), the drying up of water springs needed for drinking (irrigation is also drying up, and the water mills used for grinding wheat have stopped). It’s incredible what a ripple climate change can have. You wouldn’t think builders would be affected, but of course they are. Construction experts say traditional knowledge about how to build houses is dying out. Now homes have thinner walls and the roofs need less support. It just isn’t as cold as it used to be, nor does it snow as much, so we’re forgoing traditional insulation and construction techniques and materials.”

By Harming Earth,

We Harm Ourselves

SWAMI MAYATITANANDA, WISE EARTH MONASTERY

Hindu thought envisions the Earth as divine: the body of the universe is God; the Earth is the Goddess (Bhudevi). India is a sacred land connected by thousands of pilgrimage routes leading to sacred places, considered themselves to be Gods and Goddesses. Infinite numbers of Deities represent Nature; Agni, the fire of manifestation, is central to this theme. ¶Because we humans are intricately replicated from the identical principles of the cosmic nature, the seers recognized that changes caused due to indiscreet human activities would result in imbalances in seasons, rainfall patterns, crops and atmosphere, and degrade the quality of water, air and earth resources. In so doing, the human memory and intelligence, as a self-organizing, self-generating organism, becomes dull and potentially inert. This, in turn, affects our relationship to self-wisdom and our interactions with nature’s resources.

Hindu thought envisions the Earth as divine: the body of the universe is God; the Earth is the Goddess (Bhudevi). India is a sacred land connected by thousands of pilgrimage routes leading to sacred places, considered themselves to be Gods and Goddesses. Infinite numbers of Deities represent Nature; Agni, the fire of manifestation, is central to this theme. ¶Because we humans are intricately replicated from the identical principles of the cosmic nature, the seers recognized that changes caused due to indiscreet human activities would result in imbalances in seasons, rainfall patterns, crops and atmosphere, and degrade the quality of water, air and earth resources. In so doing, the human memory and intelligence, as a self-organizing, self-generating organism, becomes dull and potentially inert. This, in turn, affects our relationship to self-wisdom and our interactions with nature’s resources.

Nature’s new severity: Deforestation in Nepalese middle hills results in the washing away of precious topsoil during monsoons, river silt-up and swollen rivers carving greater swaths, taking away valuable agriculture land. Banks of upper watersheds are breaking, flooding lower areas.

Ether, air, fire, water, earth, planets, all creatures, directions, trees and plants, rivers and seas—they all are organs of God’s body. Remembering this, a devotee respects all species.

SRIMAD BHAGAVATA MAHAPURANA (2.2.41)

WHEREVER YOU LOOK IN HINDU SCRIPTURE, you find references reinforcing the central pillar of Hindu environmental thought: All is God, all is Divine, all is to be treated with reverence and respect, all is sacred. As O.P. Dwivedi points out, three grand concepts build on this truism: Vasudeva sarvam (the Supreme resides in all beings); Vasudhaiva kutumbakam (the family of Mother Earth—the original “global village”); and Sarva bhuta hita (the welfare of all beings) (Hinduism and Ecology). Add to those the law of karma—by which the effects of our deeds return to us—and you have a deep repository of ecological thought and practice.

At the highest level, there is no distinction in composition between the world we perceive and the Divine. Rather than being created out of a separate substance, the universe and everything within it, the planet we inhabit and everything upon it, is emanated from the Divine. The process of creation is analogous to a spider creating its web. The Mundaka Upanishad states: “As a spider spins and withdraws its web, as herbs grow on the earth, as hair grows on the head and body of a person, so also from the Imperishable arises this universe” (1.1.7).

The Brihadaranayaka Upanishad (2.5.1) speaks of creatures and the creation: “This earth is honey for all creatures, and all creatures are honey for this earth. This shining, immortal person who is in this earth and with reference to oneself, this shining immortal person who is in the body, he, indeed, is just this self. This is immortal; this is Brahman; this is all.”

Vasudeva Sarvam, Divinity in All

The attitude of Vasudeva sarvam bestows reverence for all things. It contrasts starkly with the dominant outlook today, rooted in scientific materialism and dualistic Western metaphysics, in which humans are separate from nature and God is separate from both. While Western civilization considers human life to be sacred, Hinduism views all of life, all of existence, as sacred. The mainstream of the modern environmental movement recognizes the folly of taking more from nature than can be perpetually regenerated—but only because the eventually resulting ecosystem collapse would cause harm to humans. In general, the environmental movement stops well short of recognizing intrinsic value in what is nonhuman. Frequently, it denies the sacred altogether.

Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam, Global Village

Once we understand that everyone and everything we see is an expression and emanation of the Divine, we naturally embrace the globe as a village, Vasudhaiva kutumbakam. As Dwivedi expresses it, Mother Earth “supports us with Her abundant endowments and riches; it is She who nourishes us; it is She who provides us with a sustainable environment; and it is She who, when angered by the misdeeds of Her children, punishes them with disasters.” Dwivedi’s words are an apt paraphrase of the Atharva Veda’s 63-verse Bhumi Sukta, Hymn to Earth, which focuses on nature and the dependence of humans upon Mother Earth, how She does not discriminate between species. To Her, all are important.

Dwivedi highlights a prayer for the preservation of the original fragrance of the Earth so that it can be sustained for future generations, and another specifying that when digging is done in the Earth, it should be done in a way that no serious damage is done to Her body or appearance. Each reinforces the understanding that humans are not separate from the environment and have no authority over it, other species or other humans.

The modern scientific concept expressed in the Gaia Theory—of Earth being a giant, self-regulating organism seeking to create optimal conditions for life—is not far removed from the views expressed in the Prithivi Sukta (another Vedic hymn to Goddess Earth), even though the modern theory makes no reference to the Divine, or to conscious causality or emotion in the creation of natural disasters. However, with a slight shift of perspective, it is easy to see the connection between the challenges we are experiencing (global warming and the ensuing host of environmental changes) and our misdeeds toward Mother Earth. We have unbalanced the atmosphere through excessive greenhouse gas emissions and wantonly destroyed precious forests for logging and conversion to agriculture. The resulting upheavals can be viewed as the manifestation of a natural response, as the Earth attempts to restore a more natural order and thus protect her many and varied forms of life.

An Ancient Peace Chant

May the Goddess Waters be auspicious for us to drink. May they flow, they flow, with blessings upon us.

May the Goddess Waters be auspicious for us to drink. May they flow, they flow, with blessings upon us.

May the Earth be pleasant and free of thorns as our place of rest. May She grant us a wide peace.

May the Divine Waters which grant us blessings, may they sustain us vigor and energy, and for a great vision of delight.

May we partake of that which is their most auspicious essence, as from loving mothers.

May the Heaven grant us peace, and the Atmosphere. May the Earth grant us peace, and the Waters. May the plants and the great forest trees give us their peace. May all the Devas grant us peace; may Brahman grant us peace. May the entire universe grant us peace. May that supreme peace come to us. May that peace dwell in me.

Take this firm resolve: May all beings look at me with the eyes of a friend. May I look at all beings with the eyes of a friend. May we all look at each other with the eyes of a friend.

SHUKLA YAJUR VEDA (36.12-15, 17-18)

TRANSLATION BY VAMADEVA SHASTRI

Perhaps It Is Possible to Bring Forth a New Era

DR. ARVIND SHARMA, PROFESSOR OF COMPARATIVE RELIGION AT MCGILL UNIVERSITY, MONTREAL

There is the doctrine of the four yugas. We are living in the Kali Yuga, which started around 3102 BCE. This is the worst of all the four ages, and things are going to go downhill. However, there is a very important point which is often overlooked. The same texts that talk about these ages, like the Manusmriti, also say that the king is the maker of the age. That is, the sequence of the ages can be reversed by a political initiator, to put it in modern idiom. This is found in the Mahabharata and in many scriptures from ancient India in which the king said that he established the golden age in this age of the Kali Yuga. So here we have a very clear provision of intervention to prevent environmental degradation, especially by the state.

There is the doctrine of the four yugas. We are living in the Kali Yuga, which started around 3102 BCE. This is the worst of all the four ages, and things are going to go downhill. However, there is a very important point which is often overlooked. The same texts that talk about these ages, like the Manusmriti, also say that the king is the maker of the age. That is, the sequence of the ages can be reversed by a political initiator, to put it in modern idiom. This is found in the Mahabharata and in many scriptures from ancient India in which the king said that he established the golden age in this age of the Kali Yuga. So here we have a very clear provision of intervention to prevent environmental degradation, especially by the state.

The Impact of Automobiles: Transportation is one of the greediest energy consumers and one of the largest sources of greenhouse gas and other air pollution. The contribution of fossil fuel-based transport to a country’s total emissions varies from nation to nation. In rich nations, and increasingly in rapidly expanding economies such as China, India and Brazil, motorized transport is one of the most important areas in which we can reduce our environmental impact. Powerful reductions can be achieved through moving away from the internal combustion engine and toward electric-powered transport and increased bicycle usage, along with greater public transportation and construction of more walkable communities.

Sarva Bhuta Hita, Welfare of All Beings

Once we understand Mother Earth’s protection of life, we can understand how humans should act toward one another and all other forms of life. Thus, we arrive at Sarva bhuta hita, “enhancing the common good of all beings.” When we know that all is sacred, all is God, and we are all children of Mother Earth, our behavior and even our desires change accordingly. We want to enhance the common good and balance our individual needs with those of the extended family of life. It becomes natural to follow dharma. But even then, it is not necessarily easy to determine the best course of action for supporting the common good in specific situations.

Karma

An understanding of karma ties together these three grand concepts, informing us that our current condition is the combined product of our past actions (in this life and previous incarnations) and actions that we take today. In this way, we are constantly creating our future, in the months, years, decades and even lifetimes to come. Clearly, our actions also influence our family and community, today and into the future.

Consider climate change, one of the most pressing environmental issues of our time, as a lesson in karma. How did we cause greenhouse gas concentrations to rise so high that they are forcing myriad climatic changes? Through well over a century of burning fossil fuels, through cutting down forests and through increased raising of animals for meat. Many of our parents, grandparents and great-grandparents (to a lesser degree) all did this without thought of the future consequences. Indeed, it wasn’t until the last decades of the 20th century that we began to recognize that there might be a long-term problem with this behavior. It’s clear as day: we, the human race, created the threatening circumstances we and future generations now face. Our environmental karma is of our own creation.

As a global civilization, we continue the same practices today, even though the negative effects are becoming more and more apparent by the month. In some ways, it will be extremely hard to stop our harmful practices, not to mention reversing the damage we have already caused.

Who will suffer the worst of the environmental problems we have created? Certainly not our parents. Even those of us who are adults today may not bear the brunt of them. It will be our children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren who suffer the consequences.

Supposing a forest at the headwaters of a large river is excessively cleared. The loggers may accrue immediate economic benefits, but over the years great numbers of animals may die due to habitat loss, and disastrous flooding may result as hillsides wash away and cause blockages downstream. Similarly, emissions of invisible greenhouse gases create atmospheric overload and dangerous climatic changes decades after the actions that caused them. Such long-term environmental changes, one leading to another, cannot be easily halted or reversed.

God Is Everywhere

YOGINI SRI CHANDRA KALI PRASADA MATAJI,

SRI KALI GARDENS ASHRAM, ANDHRA PRADESH

Hindu philosophy is based on the truth that there is one Supreme Power that is the sustaining force of the entire creation. Personal transformation starts with realization of this Supreme Power within one’s own self. The aspirant will then be able to experience that power all around him. Thus he understands that this power is universal, nondual, indivisible and eternal. He sees unity in diversity. He will not see his fellow human beings as different from him and so does not fear. Such a person is full of compassion and unlimited love. He will work towards peace and prosperity of not only mankind but all of nature. This is accomplished only through faith and surrender to that Supreme Power and under the able guidance of the spiritual teacher who is an embodiment of that power. Healing the Earth is possible by exchanging ideas and restoring spiritual values. Peace is much needed in today’s world. Unless each individual changes his behavior and thinking for his own progress and for the world at large, peace cannot be established.

Hindu philosophy is based on the truth that there is one Supreme Power that is the sustaining force of the entire creation. Personal transformation starts with realization of this Supreme Power within one’s own self. The aspirant will then be able to experience that power all around him. Thus he understands that this power is universal, nondual, indivisible and eternal. He sees unity in diversity. He will not see his fellow human beings as different from him and so does not fear. Such a person is full of compassion and unlimited love. He will work towards peace and prosperity of not only mankind but all of nature. This is accomplished only through faith and surrender to that Supreme Power and under the able guidance of the spiritual teacher who is an embodiment of that power. Healing the Earth is possible by exchanging ideas and restoring spiritual values. Peace is much needed in today’s world. Unless each individual changes his behavior and thinking for his own progress and for the world at large, peace cannot be established.

Stop All Killing & Exploitation

DADA J.P. VASWANI, SADHU VASWANI MISSION, MAHARASHTRA

Reverence is the root of Hinduism, reverence for all life. People worship trees, they worship mountains, they worship the universe, the spiritual world. Now it is all gone. Hinduism can save the world from global annihilation. Hinduism has the potency and the power. But today people don’t pay attention to our great ones. ¶It has seemed to me that there can be no peace on Earth, that there can be no peace among nations, until we stop all killing. Stop all killing! No sentient creature must be killed. If I kill an animal for food, I will not hesitate to kill a fellow human being whom I regard as an enemy. Humanity will learn one day that there is no other way to peace than vegetarianism. Life is a gift of God. ¶Among all the creatures, man is the only one who has been given the power to meddle with the ecological balance. Therefore, he has great responsibility to see that all types of life are preserved. All life should be regarded as sacred, for there is but one life that flows into all. This one life sleeps in the mineral and the stone. This one life stirs in the vegetable and the plant. This one life dreams in the bird and the animal. This one life is awake in man.

Reverence is the root of Hinduism, reverence for all life. People worship trees, they worship mountains, they worship the universe, the spiritual world. Now it is all gone. Hinduism can save the world from global annihilation. Hinduism has the potency and the power. But today people don’t pay attention to our great ones. ¶It has seemed to me that there can be no peace on Earth, that there can be no peace among nations, until we stop all killing. Stop all killing! No sentient creature must be killed. If I kill an animal for food, I will not hesitate to kill a fellow human being whom I regard as an enemy. Humanity will learn one day that there is no other way to peace than vegetarianism. Life is a gift of God. ¶Among all the creatures, man is the only one who has been given the power to meddle with the ecological balance. Therefore, he has great responsibility to see that all types of life are preserved. All life should be regarded as sacred, for there is but one life that flows into all. This one life sleeps in the mineral and the stone. This one life stirs in the vegetable and the plant. This one life dreams in the bird and the animal. This one life is awake in man.

The Price of “Progress:” Kayapo Indians from the Xingu Reserve in Brazil watch as a bulldozer relentlessly carves a road through the forest to give loggers access to harvest the natives’ precious mahogany trees.

The Five Elements

In the Hindu conception of the cosmos and the environment, the five great elements (pancha mahabhutas) are central: space (akasha), air (vayu), fire (agni), water (apas) and earth (prithivi). All emanate from prakriti (cosmic matter). Though each element has its own form and characteristics, all are interconnected and interdependent. The Taittiriya Upanishad tells us: “From Brahman arises space, from space arises air, from air arises fire, from fire arises water, and from water arises earth.”

Akasha, space, is the most subtle of the five, and there is no place where it is not. Akasha is not nothingness, like the popular conceptions of outer space; on the contrary, akasha is absolute fullness. K.L. Seshagiri Rao explains, “Akasha represents openness, brightness, expansiveness and the fullness of blooming capacity.”

Vayu, air, manifests on Earth as the atmosphere, the protective blanket of gases that surrounds the planet, regulating temperature and preventing excessive solar radiation from reaching Earth’s surface. Air connects and affects everything, from animals breathing in and out, to plants exchanging oxygen for carbon dioxide. Weather, which so defines daily life, is a function of air in collaboration with the other elements. Even rocks are subject to wind erosion.

Agni, fire, has been worshiped since ancient times. Fire purifies, fire destroys, fire inspires. From the Sun, to lightning, to fire in its mundane and sacred forms, agni brings warmth and visibility to the world. The Vedas sing its praises: “I magnify the Lord (Agni), the divine, the priest, minister of the sacrifice, the offerer, supreme giver of treasure. To you, dispeller of the night, we come with daily prayer, offering to you our reverence” (Rig Veda 1.1.1&7).

Water, apas, is the source and sustainer of life. Its immense sacredness is rivalled only by its practical value to human agriculture, health, enjoyment and the development of civilization. In the form of Earth’s rivers, water is so vast in its life-giving and life-sustaining properties that it is worshiped as the mother of life, as Mother Ganga.

Earth, the densest of the five elements, is the ground upon which life takes place. It is the body of the Divine, a living organism, metaphysically, metaphorically and biologically. Hindus have cognized this for millennia, knowing that all creatures are intimately connected to the Earth. Without its gifts we are nothing. In the latter half of the 20th century, modern science has caught up with this truth, conceiving of Earth as a self-regulating organism called Gaia, a name for which Dharani, Bhudevi or Bhumi—Hindu names for the Goddess—could easily be substituted.

Though self-regulating and dynamically interacting, the five great elements of existence can be pushed out of balance by human action, creating conditions inhospitable to life in general. What are the imbalances confronting the Earth?

Akasha is being thrown out of balance through excessive and constant noise, as is found in modern cities and towns with never-ending motor vehicle traffic, the hum of air conditioners and computer servers, blaring music, omnipresent advertisements appealing to the lower aspects of our being, televisions and video screens shoehorned into every available space. Needless to say, repose, reflection and sattvic living become difficult in such conditions.

Unbalanced vayu is seen in air pollution, especially over cities. This is caused by industrial activity, power generation from fossil fuels, and the exhaust of internal combustion engines. Brown smog is the most visible form of air pollution, but an excess of greenhouse gases also upsets vayu, causing climate change, raising temperatures and acidifying oceans. Any disturbance to vayu can also interfere with agni, as in its solar form agni is the energy which heats the air, powers the water cycle, and helps enable life to grow. Each of those processes is affected by pollution.

The element water has been drastically disturbed by human activity. We have dumped human sewage and industrial effluent into rivers and oceans; farmers have irrigated so aggressively that water tables have become lowered, and have allowed runoff of chemical fertilizers and pesticides into streams; we have built massive dams and diverted entire rivers at the expense of wildlife and the people who live in the watersheds; and we have disposed of non-biodegradable trash and plastics in rivers, ponds and wetlands. The same activities that unbalance vayu and agni, causing climate change, also affect water, causing ocean acidification, coral bleaching and glacial melting.

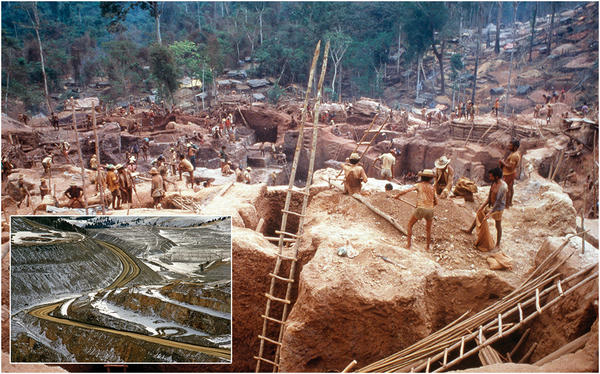

Earth unbalanced is the most obvious. Vast tracts of forest are cleared for timber and agriculture—often for industrial monoculture farming or cattle ranching. Mining for coal, bauxite, gold and hundreds of other minerals scars mountainsides and removes mountaintops. Human demand for resources—extremely inequitable between rich and poor nations—is causing habitat loss and species extinction at a level unprecedented in the modern history of the planet. Human population is increasing at the expense of virtually every other species. To sustainably supply our current levels of resource consumption would require one and one half planets. By 2030, that increases to two planets. We can hope that a new balance will eventually be reached; but the vast majority of climate scientists say that in that new balance, the Earth will be less fertile than now. Earth has undergone radical changes many times. Ice ages come and go in predictable cycles. Species are decimated and new life emerges. Temperatures oscillate, oceans rise and fall. This is not the first challenge to life Earth has faced, but it is the first in which we, the human race, are playing a major role.

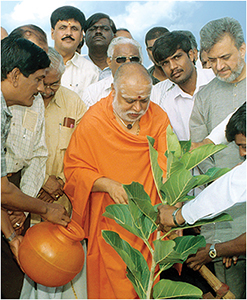

Fifty Million Saplings

Mother Earth is adorned with mountains, hills, plains, heights, slopes, forests, plants and herbs. Strength-giving and nourishing, She takes care of every creature that breathes. She gives shelter to all who are seekers of truth, who are tolerant and have understanding. ¶Much has been said about protecting the environment, but the common man must understand how he can contribute to this effort. Protecting the environment and making the world a better place for all living beings starts right from our house. Plant trees. ¶His Holiness Jagadguru Sri Sri Sri Balagangadharanatha Swamiji, 71st pontiff of Sri Adichunchanagiri Mahasamsthana Math, resolved to maintain the ecological balance by adorning Mother Earth with a new patch of green. In association with the government of Karnataka, Swamiji formed the Karnataka Vanasamvardhana Trust with the goal of planting five crore saplings (50 million). The project was completed in 2010 with the help of several organizations. Swamiji provided tree guards to protect the plants and supplied tractors to help with the work. His message is, “Come, let us join together in protecting the environment; each one of us is required to contribute to reduce our carbon footprint on this Earth.”

Mother Earth is adorned with mountains, hills, plains, heights, slopes, forests, plants and herbs. Strength-giving and nourishing, She takes care of every creature that breathes. She gives shelter to all who are seekers of truth, who are tolerant and have understanding. ¶Much has been said about protecting the environment, but the common man must understand how he can contribute to this effort. Protecting the environment and making the world a better place for all living beings starts right from our house. Plant trees. ¶His Holiness Jagadguru Sri Sri Sri Balagangadharanatha Swamiji, 71st pontiff of Sri Adichunchanagiri Mahasamsthana Math, resolved to maintain the ecological balance by adorning Mother Earth with a new patch of green. In association with the government of Karnataka, Swamiji formed the Karnataka Vanasamvardhana Trust with the goal of planting five crore saplings (50 million). The project was completed in 2010 with the help of several organizations. Swamiji provided tree guards to protect the plants and supplied tractors to help with the work. His message is, “Come, let us join together in protecting the environment; each one of us is required to contribute to reduce our carbon footprint on this Earth.”

True wealth: Men encircle an endangered rosewood tree, the largest in Yanaipallam, Tamil Nadu; thousands of potted saplings being propagated for the fifty-million tree project; Sri Balagangadharanatha Swami takes part in ceremoniously planting a teak tree

Treatment of Other Creatures

The Hindu vision of existence and this planet is replete with examples of how consciousness permeates everything, from the obvious and animate (humans, animals, plants) to the less obvious and inanimate (rivers, stones, mountains). No part of existence is without the divine presence. Nothing exists separate from God. The practical manifestation of this understanding is the virtue of ahimsa, nonviolence in thought, word and deed. Seeing the presence of God in all life and therefore not harming it is the foundational ethic of Hindu thought.

The Hindu reverence for the cow epitomizes this respect for all creatures. The cow symbolizes all other animals and the Earth itself. It is the nourisher, ever-giving and undemanding, representing life and the sustenance of life. The cow is generosity incarnate, taking nothing but water and grass and continuing to give and give milk. It also symbolizes dignity, strength, endurance, maternity and selfless service. The cow and her life-giving gifts, foremost among them milk and ghee, are essential in Hindu worship. Through the labor of the bull, where mechanized agriculture is not the norm, fields are plowed and grains and vegetables are grown. Veneration of the cow instills the virtues of gentleness, receptivity and connectedness with nature. Protection of the cow is important both ethically and practically.

Mahatma Gandhi observed, “One can measure the greatness of a nation by the way it treats its animals. Cow protection to me is not mere protection of the cow. It means protection of all that lives and is helpless and weak in the world. The cow means the entire subhuman world.”

We may question whether the subhuman world is weak and helpless. In many ways, it is modern humans that are the helpless ones, absent high technology. But Gandhi’s words are profound at the core. The way in which a people treats animals—with respect and dignity on one end of the spectrum, or as commodities for human ownership, use and disposal at the other—says much about them and likely indicates the way in which they treat one another as well.

A central part of treating animals with respect is not killing them for food. That said, both traditional and current Hindu teachings contain various views on meat-eating. Priests and religious leaders, as well as those people pursuing yoga and meditation, tend to be vegetarian. On the other hand, soldiers, police officers and others whose duties require the maintenance of aggressive qualities generally eat meat. Furthermore, many people may eat primarily vegetarian diets out of economic necessity as much as ethical virtue, but will eat meat on special occasions.

Swami Dayananda Saraswati cites the Tirukural, saying, “Killing animals and eating their flesh is against all morality.” Swami Tyagananda of the Ramakrishna Order offers, “In the tradition I come from, we are not fanatic about vegetarianism, but we recognize that food that is filled with sattva, which is vegetarian food, can be helpful in one’s own spiritual practice.” Professor Arvind Sharma reminds us that historically Hinduism has been more guarded than Jainism in espousing strict vegetarianism: “A passage in the Manusmriti says there is nothing wrong with eating meat or drinking wine, but abstention therefrom is highly meritorious. It’s a no-fault position; you can eat meat, but it’s better not to.”

However, knowing what we do now about the impact of a meat-centric diet on the environment—combined with modern problems of hunger and land use, plus deplorable modern methods of raising livestock—the merits of a vegetarian diet go far beyond furthering an individual’s spiritual progress. Adopting a vegetarian diet benefits everyone and everything. It dramatically lowers one’s environmental impact, since raising animals for food requires far more resources, in terms of energy and land, grow than growing vegetables of the same caloric value and nutritional content.

The modern industrial, chemical-based farming methods of growing grains and vegetables are damaging to the environment, but the factory farming of animals is even more so. A study carried out in the Netherlands revealed that if enough meat eaters adopted a vegetarian diet, the costs of mitigating the damages caused by climate change would be reduced 70 percent by 2050. Even if large numbers of people merely stopped eating meat from ruminant animals, the cost of combatting climate change would drop by 50 percent. (http://bit.ly/climate-diet)

What Will it Take to Avert Dire Climate Change?

The average per-capita carbon footprint for people living in the United States is approximately 18 tons per year, though it has fallen in the past few years due to recession. The average in Europe is about half that, with China coming in at about 6 tons. In India the number drops to roughly 2 tons. If the goal is to keep temperature rise below 2° Celsius—the threshold above which many dangerous climatic changes are said to become unavoidable—and if we accept that every human has the right to similar levels of development, then 2 tons is roughly what each human being needs to produce. In this one statistic the enormity of combatting climate change becomes clear.

The average per-capita carbon footprint for people living in the United States is approximately 18 tons per year, though it has fallen in the past few years due to recession. The average in Europe is about half that, with China coming in at about 6 tons. In India the number drops to roughly 2 tons. If the goal is to keep temperature rise below 2° Celsius—the threshold above which many dangerous climatic changes are said to become unavoidable—and if we accept that every human has the right to similar levels of development, then 2 tons is roughly what each human being needs to produce. In this one statistic the enormity of combatting climate change becomes clear.

Hindu Virtues

Versus Consumerism

Hinduism’s numerous classic restraints and practices, the yamas and niyamas, offer lots of practical guidance for those wishing to minimize their impact on the environment. If we are to observe non-stealing, asteya, we cannot use natural resources at unsustainable rates; when we do so, we jeopardize the life of future generations. This is effectively a form of stealing. If every human on the planet consumed resources at the level of the United States, we would need 4.5 earths to supply everyone’s needs. That decreases slightly if everyone lived like the average European or Japanese citizen, but still not to ecologically sustainable levels.To reach that point, consumption like that of the average Thai citizen, or less, is required. ¶If more people practiced santosha, contentment, we would greatly reduce the impact of consumerism on the planet—from rising greenhouse gas emissions, to chemical pollution, e-waste from countless short-lived electronic products, and the myriad consumer goods that get used and thrown away each year in the wealthy and growing nations of the world. Contentment involves living in constant gratitude for your health, your friends and those belongings which you do own, not complaining about what you don’t possess, as well as viewing every moment in life as an opportunity for spiritual growth and development. All of this has great positive environmental impact. Being contented in the moment, living in the eternal now, insulates you from consumerism, allowing you to embrace a simple life, caring for what you have and living within your means.

Hinduism’s numerous classic restraints and practices, the yamas and niyamas, offer lots of practical guidance for those wishing to minimize their impact on the environment. If we are to observe non-stealing, asteya, we cannot use natural resources at unsustainable rates; when we do so, we jeopardize the life of future generations. This is effectively a form of stealing. If every human on the planet consumed resources at the level of the United States, we would need 4.5 earths to supply everyone’s needs. That decreases slightly if everyone lived like the average European or Japanese citizen, but still not to ecologically sustainable levels.To reach that point, consumption like that of the average Thai citizen, or less, is required. ¶If more people practiced santosha, contentment, we would greatly reduce the impact of consumerism on the planet—from rising greenhouse gas emissions, to chemical pollution, e-waste from countless short-lived electronic products, and the myriad consumer goods that get used and thrown away each year in the wealthy and growing nations of the world. Contentment involves living in constant gratitude for your health, your friends and those belongings which you do own, not complaining about what you don’t possess, as well as viewing every moment in life as an opportunity for spiritual growth and development. All of this has great positive environmental impact. Being contented in the moment, living in the eternal now, insulates you from consumerism, allowing you to embrace a simple life, caring for what you have and living within your means.

Changing Landscapes: In this section of Brazil, cattle farming has replaced the tropical rainforest; increasingly, wind turbines offer an alternate source of energy in many regions of the world

What Can We Do?

Humanity will not make progress in resolving the myriad environmental problems we face without dedicating time, effort and willpower. Determined action is needed on all levels: personal, community and national. Even in ancient times—when the world population was much sparser than today and our potential impact was miniscule in comparison—rulers and rishis alike recognized that guidance and regulation of human activities was needed to protect the environment.

In numerous places, the Vedas and other scriptures encourage environmental protection. “Do not harm the environment; do not harm the water and the flora; Earth is my Mother, I am Her son; may the waters remain fresh, do not harm the waters. . . . Tranquil be to the atmosphere, to the earth, to the waters, to the crops and vegetation.” The sacred law books are even more specific, for example: “Let him not discharge urine or feces into the water, nor saliva, nor clothes defiled by impure substances, nor any other impurity, nor blood, nor poisons” (Manu Samhita IV. 56). Fines are specified for offenses against the environment, such as damaging trees. Professor Arvind Sharma explains, “Harming a tree was considered on par with physical assault of a person. In one verse Manu tells us how much you have to compensate a person you have physically injured. In the next verse it says: ‘For injuring any kind of tree a fine should be imposed proportionate to its utility.’”

Three types of forests were identified: shivan, forests that provide prosperity; tapovan, forests for contemplation; mahavan, natural forests where all species can find shelter. Vedic scholar and environmental campaigner Ranchor Prime shares, “Once some of the original forest was cleared,... Vedic culture required that another kind of forest be established in its place. To completely remove the forest was simply not acceptable. It was the source of natural wealth, such as fodder, timber, roots and herbs. Moreover, the trees guaranteed the fertility of the soil and purified the air and water.”

In recent memory, and historically, we have a number of examples of communities and individuals applying the principles of good environmental stewardship that are latent in Hindu thought.

The Bishois, founded by Guru Jambheshwar in the 15th century, are sometimes called the first environmentalists of India. Originally from the Marwar area of Rajasthan, they now number one million and live more widely across India, practicing environmental conservation, protection of trees and animals as part of daily religious duty. Two of the sect’s 29 injunctions are directly concerned with environmental protection: 1) Be compassionate to all living beings, and 2) Don’t cut green trees. Not killing animals is a given.

In the early 1970s, the Chipko movement took to tree hugging to prevent felling of forests in Chamoli district, Uttarakhand. Women from villages recognized that economic and environmental devastation would result from the logging that had been authorized by the Government Department of Forests and staged a direct action campaign to stop it. One need not be part of a spiritual community to uphold environmental protection. There is much that each of us can do, if we observe the traditional virtues with an environmental focus and take to heart the environmental themes in Hindu scripture and the teachings of Mahatma Gandhi.

Though Gandhi was not directly concerned with the environment, and still less with conservation of nature, many of his teachings have environmental implications. In fact, his life and message have been inspirational for generations of environmental writers and campaigners. His concerns about industrialization, about the treatment of animals and the virtues of vegetarianism, about the importance of recycling, about preserving and strengthening local production of goods, all have direct applicability to today’s problems. His aphorism, “There’s enough in the world for everyone’s need but not everybody’s greed,” is as vital today as it was a hundred years ago. Indeed, on the streets of Copenhagen during the COP15 UN climate change conference in December 2009, campaigners prominently passed out round stickers displaying the words “Need Not Greed” and the iconic image of Gandhi, simply dressed, walking staff in hand.

Central to applying that aphorism are two ethics: sanyam (restraint) and maryada (limitation). As Professor Arvind Sharma puts it, “You refrain from drinking or eating too much not because there are laws against doing that, but out of a sense of propriety and decency.” You practice restraint and limitation not because you are forced to, but because it’s part of your lifestyle.

Another key is the principle of aparigraha, simplicity, which is closely tied to santosha, contentment. When we live every day with a sense of gratitude for our health, while seeking serenity in life, it becomes that much easier to live simply and not identify with what we have or don’t have, what our neighbors have that we don’t, or what is being advertised as the key to happiness. Gandhi advised, “Live simply, so others may simply live.”

Having Concern for Others

SWAMI AVDHESHANAND GIRI, JUNA PEETH AND ACHARYA SABHA, UTTARAKHAND

The approach that we should take the maximum wealth available to us from nature, be it oil or metals, and that we should maximize our power with nuclear weapons—these contribute to our global problems. Our Hindu dharma has given us certain important values to implement in our day-to-day lives, including being satisfied with whatever we have. Learn to share, learn to give first, and then enjoy. This attitude will bring about harmony in society. Hinduism is a tradition which has always cared for the growth and religious sensitivities of each and every individual—not only cared for but helped them equally to grow individually. Today the absence of this attitude has created agitation and given rise to crime and imbalance in society. The attitude that “I shall grow at the cost of others” is considered improper in the Hindu religion. It is a great sin against ahimsa, the principle of nonviolence, to be insensitive to the rights and demands of others and to afflict pain or hurt on them—not only physically, but by hurting their religious sentiments, their belief systems.

The approach that we should take the maximum wealth available to us from nature, be it oil or metals, and that we should maximize our power with nuclear weapons—these contribute to our global problems. Our Hindu dharma has given us certain important values to implement in our day-to-day lives, including being satisfied with whatever we have. Learn to share, learn to give first, and then enjoy. This attitude will bring about harmony in society. Hinduism is a tradition which has always cared for the growth and religious sensitivities of each and every individual—not only cared for but helped them equally to grow individually. Today the absence of this attitude has created agitation and given rise to crime and imbalance in society. The attitude that “I shall grow at the cost of others” is considered improper in the Hindu religion. It is a great sin against ahimsa, the principle of nonviolence, to be insensitive to the rights and demands of others and to afflict pain or hurt on them—not only physically, but by hurting their religious sentiments, their belief systems.

Enviromental Protection

As a Spiritual Practice

SWAMI TYAGANANDA , RAMAKRISHNA MISSION, BOSTON

Hinduism sees the cosmos as pervaded by the Divine. So, taking care of the universe is the same as worshiping the Divine. Environmental protection, preventing environmental degradation, becomes a form of spiritual practice, a form of worship. I think this ideal of oneness provides us the foundation for understanding the close connection we have with the environment. ¶Ramakrishna Paramahansa, the founder of the order to which I belong, experienced divine immanence in a radical way. In a state of samadhi, he once stood before a patch of green grass and experienced excruciating pain when a person walked over that grass. It’s not simply a theoretical concept; in actual practice we really are one. It is one big ocean of matter in which every material object, including our own body, is part. I sometimes call existence the four oceans. At the level of matter, there is one continuous whole. Similarly, at the level of thought, when we speak about the cosmic mind, each mind can be seen as a small wave in this ocean of thoughts and ideas. Even at the level of emotions and feelings, it’s one big ocean. And, of course, at the level of spirit it’s one big ocean. This oneness is something which mystics have realized, and we also can realize it. That is why I feel that in helping and taking care of the environment we are really taking care of our own self. By hurting the environment we are hurting ourselves.

Hinduism sees the cosmos as pervaded by the Divine. So, taking care of the universe is the same as worshiping the Divine. Environmental protection, preventing environmental degradation, becomes a form of spiritual practice, a form of worship. I think this ideal of oneness provides us the foundation for understanding the close connection we have with the environment. ¶Ramakrishna Paramahansa, the founder of the order to which I belong, experienced divine immanence in a radical way. In a state of samadhi, he once stood before a patch of green grass and experienced excruciating pain when a person walked over that grass. It’s not simply a theoretical concept; in actual practice we really are one. It is one big ocean of matter in which every material object, including our own body, is part. I sometimes call existence the four oceans. At the level of matter, there is one continuous whole. Similarly, at the level of thought, when we speak about the cosmic mind, each mind can be seen as a small wave in this ocean of thoughts and ideas. Even at the level of emotions and feelings, it’s one big ocean. And, of course, at the level of spirit it’s one big ocean. This oneness is something which mystics have realized, and we also can realize it. That is why I feel that in helping and taking care of the environment we are really taking care of our own self. By hurting the environment we are hurting ourselves.

What Are the Greatest Treasures? Gold mining, like at this site, is tearing up the Brazilian rainforest and ruining many of the sacred rivers; inset, a devastating strip mining operation in Colorado

What Is Being Done?

As awareness of the seriousness of our current environmental problems grows, a number of Hindu organizations have begun taking action to help reduce the environmental impact of their activities and address some of the bigger problems, such as deforestation and climate change.

With tens of thousands of pilgrims visiting Tirumala’s Sri Venkateswara Temple daily and about 30,000 of them being fed by the communal kitchen, a lot of energy is required to cook those meals. Prior to 2008, generators powered by diesel fuel were used; but since then, solar-powered cookers have been installed, massively reducing the greenhouse gas emissions. Just a few months ago, Tirumala took action to stop plastic litter pollution, replacing the plastic bags used to distribute prasad with ones made of cloth, paper or jute, and using paper or reusable cups, instead of plastic ones, for serving tea and water.

In Uttarakhand, Swami Chidanand Saraswati has made preservation of the environment a top priority. He has been working to raise public awareness and influence government policy to reduce pollution of the River Ganga (sidebar page 53).

People are becoming more aware of the wide-ranging effects of deforestation: it accelerates erosion in mountain areas, destroys habitat for animals and imperils resources that are essential for people’s livelihoods. It contributes to climate change by reducing the ability of the Earth to absorb greenhouse gas emissions and exacerbates the damage done by cyclones and rising sea levels.

Reforestation or afforestation programs can help stop such environmental damage. A number of groups have begun undertaking this work. Soham Baba Mission has begun planting trees around Kolkata and in the Sundarbans. In coastal areas such as these, healthy forests will reduce damage from cyclones and, in the future, from rising sea levels. Adichunchanagiri Math has just completed a program of planting 50 million trees in Karnataka (sidebar, page 45). Groups such as the Pan Himalayan Grassroots Development Foundation are helping local peoples restore their community forests, thereby improving water security, maintaining biodiversity and, ultimately, helping local farmers maintain their livelihoods while ensuring that the environment is also protected. And by absorbing greenhouse gas emissions, forestation can help slow climate change, thereby reducing the melting of glaciers hundreds and thousands of miles away.

On a Personal Level

MATTHEW MCDERMOTT, SENIOR WRITER FOR TREEHHUGGER.COM & PLANETGREEN.COM

While some environmental issues seem beyond the control of the individual, there is still much a person or a family can do. Many lists of things you can do to green your life focus on myriad small steps, such as recycling. But to get an overview, there are three important areas on which to concentrate: what you eat, how you use energy and how you get around.

While some environmental issues seem beyond the control of the individual, there is still much a person or a family can do. Many lists of things you can do to green your life focus on myriad small steps, such as recycling. But to get an overview, there are three important areas on which to concentrate: what you eat, how you use energy and how you get around.

1. Your Diet: The environmental benefits of being vegetarian, particularly when you also eat organically grown produce, are numerous. A vegetarian diet reduces your personal carbon emissions by over one ton per year, compared to someone who eats meat, while a vegan diet reduces it even further.

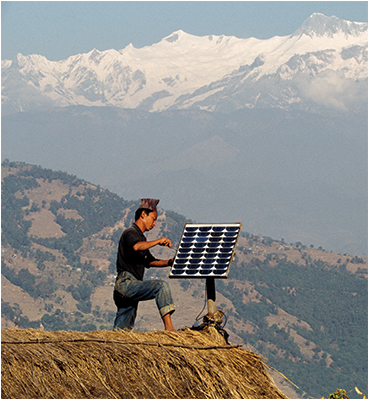

2. Your Power: If your electricity supplier offers an option to use renewable energy, choosing this is a great way to lower your home’s environmental impact. Whether you have such an option or not, there are many ways to reduce your power consumption and thus be more Earth friendly: go solar, improve insulation, install timers and motion sensors, air-dry your clothes, use rechargeable batteries, turn off lights, use on-demand gas water heaters and LED lights, hand tools rather than power tools, etc.

3. Your Transportation:Choose the least damaging way of getting from point A to point B, the one with the lowest carbon footprint. Aviation, for example, is hugely energy intensive. Just one long flight a year, say New York to Los Angeles or London, nearly equals in carbon emissions the entire yearly emissions of the average Indian citizen. A train or bus creates a small fraction of the pollution. Choose a car with high fuel efficiency and share the ride with others. For short daily journeys, walking and bicycling are by far best for the environment—and for your health and finances.

Alternate Energy: A Gurung worker fixes solar panels, maintaining a positive alternative source of energy for a house in Pulimarang, Nepal

Critical Mass

One hundred fifty years ago, Earth was still an open planet. Human populations and their impact were well within its capacity to absorb any harm caused. Today, with the population of China or India alone equal to that of the entire planet in 1850, human activity has expanded and escalated to the point where we are crashing into inflexible ecological boundaries. Earth is closed. We have reached critical mass; our actions, which used to be limited in impact, now impact the entire planet. Nevertheless, I am growing to believe that our crisis presents an evolutionary opportunity in human consciousness—an opportunity to address lingering inequity, waste and squander, a time where positive change is possible.

A Hindu Declaration on Climate Change

The Hindu tradition understands that man is not separate from nature, that we are linked by spiritual, psychological and physical bonds with the elements around us. Knowing that the Divine is present everywhere and in all things, Hindus strive to do no harm. We hold a deep reverence for life and an awareness that the great forces of nature—the earth, the water, the fire, the air and space—as well as all the various orders of life, including plants and trees, forests and animals, are bound to each other within life’s cosmic web. ¶Our beloved Earth, so touchingly looked upon as the Universal Mother, has nurtured mankind through millions of years of growth and evolution. Now centuries of rapacious exploitation of the planet have caught up with us, and a radical change in our relationship with nature is no longer an option. It is a matter of survival. We cannot continue to destroy nature without also destroying ourselves. The dire problems besetting our world—war, disease, poverty and hunger—will all be magnified many fold by the predicted impacts of climate change. ¶The nations of the world have yet to agree upon a plan to ameliorate man’s contribution to this complex change. This is largely due to powerful forces in some nations which oppose any such attempt, challenging the very concept that unnatural climate change is occurring. Hindus everywhere should work toward an international consensus. Humanity’s very survival depends upon our capacity to make a major transition of consciousness, equal in significance to earlier transitions from nomadic to agricultural, agricultural to industrial and industrial to technological. We must transit to complementarity in place of competition, convergence in place of conflict, holism in place of hedonism, optimization in place of maximization. We must, in short, move rapidly toward a global consciousness that replaces the present fractured and fragmented consciousness of the human race. ¶Mahatma Gandhi urged, “You must be the change you wish to see in the world.” If alive today, he would call upon Hindus to set the example, to change our lifestyle, to simplify our needs and restrain our desires. As one sixth of the human family, Hindus can have a tremendous impact. We can and should take the lead in Earth-friendly living, personal frugality, lower power consumption, alternative energy, sustainable food production and vegetarianism, as well as in evolving technologies that positively address our shared plight. Hindus recognize that it may be too late to avert drastic climate change. Thus, in the spirit of vasudhaiva kutumbakam, “the whole world is one family,” Hindus encourage the world to be prepared to respond with compassion to such calamitous challenges as population displacement, food and water shortage, catastrophic weather and rampant disease. ¶Sanatana Dharma envisions the vastness of God’s manifestation and the immense cycles of time in which it is perfectly created, preserved and destroyed, again and again, every dissolution being the preamble to the next creative impulse. Notwithstanding this spiritual reassurance, Hindus still know we must do all that is humanly possible to protect the Earth and her resources for the present as well as future generations.

PRESENTED FOR CONSIDERATION TO THE CONVOCATION OF HINDU SPIRITUAL LEADERS, PARLIAMENT OF THE WORLD’S RELIGIONS, MELBOURNE, AUSTRALIA, DECEMBER 8, 2009

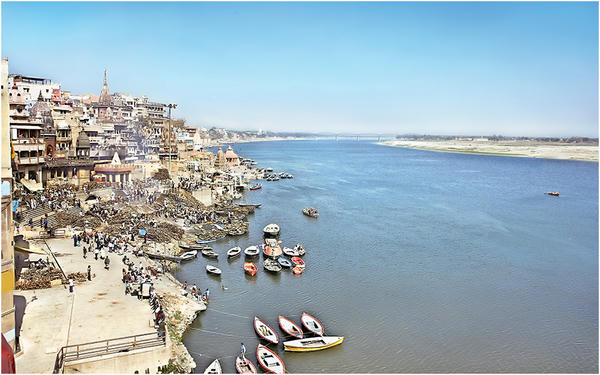

River Ganga: The cremation ghats at Varanasi add substantially to the sacred river’s burden, with corpses wrapped in white cloth and consigned to the waters. Even the introduction of flesh-eating turtles has not helped.

Example: Let’s Clean up the Ganges!

SWAMI CHIDANAND SARASWATI, PARMARTH NIKETAN, UTTARAKHAND

The Hindu younger people are more receptive to environmental protection, and when the young people are involved, the whole family will be involved. However, their parents think, “Since Ganga washes out sins, why can’t it handle this little bit of trash also?” They have to understand that Ganga can wash your sins, but it has a limit when taking care of your trash. What we call holy we can make ugly. That should not happen. The holy program should not become the ugly program. The holy places should not become ugly places. ¶Ganga does not just give spiritual life to people; it gives livelihood. Forty percent of the people in this country live in this basin where Ganga flows. If the water is not here, how will their life be here? If the water is polluted, how will their health not be polluted? It is connected with their health, their livelihoods, for generations to come. ¶Where do we begin? Action is the way. Commitment is the way. Implementation is the way. There should be an A-to-Z plan for Ganga: how the problem started, what the problem is, and how to take care of it. We must take care of it from all venues. ¶There are four kinds of pollution going into Ganga. Number one is the sewage, which is very important to handle. For sewage we are working with the government. But government alone is not enough. You need the people’s participation. To get the people’s participation you need leaders who can inspire people, who can bring them together to serve for the cause. That can be done by the spiritual leaders, the saints. Bringing the government and spiritual leaders together is being handled very carefully and successfully. ¶Number two is garbage being thrown in the Ganga. People think, “My home is my home, but the street, that’s not mine. My farm is mine, but the road is not mine. That’s the government’s road, the borough’s road, or the municipality’s road; it’s not mine.” But that is not correct. It’s not just “your home is your home.” The street is also yours. “My home, my street. My Ganga, my country.” Until we have this kind of relationship with the environment, that kind of awareness will not come. ¶Third is industrial pollution. That is a very challenging job. For that we are talking to industries. Some are nice; some are sometimes not so nice. For those we are going to the courts. We have done a few court cases, and as a result orders are given by the governments, and change is being implemented. ¶The fourth kind of pollution is religious pollution. People go on the banks of Ganga, use their flowers in worship and then throw into the Ganga their flowers and whatever plastic container they brought them in. They think Ganga can take care of it. We are stopping this. In the temples and in the ashrams, so much religious trash comes in the form of flowers. This is wonderful to offer to God but afterwards it has to be taken away. For that we have a flower van. It collects every week all those flowers—going from temple to temple, from ashram to ashram—and takes them to the field where they can make a fertilizer. All these forms of environmental degradation need to be handled simultaneously.

The Hindu younger people are more receptive to environmental protection, and when the young people are involved, the whole family will be involved. However, their parents think, “Since Ganga washes out sins, why can’t it handle this little bit of trash also?” They have to understand that Ganga can wash your sins, but it has a limit when taking care of your trash. What we call holy we can make ugly. That should not happen. The holy program should not become the ugly program. The holy places should not become ugly places. ¶Ganga does not just give spiritual life to people; it gives livelihood. Forty percent of the people in this country live in this basin where Ganga flows. If the water is not here, how will their life be here? If the water is polluted, how will their health not be polluted? It is connected with their health, their livelihoods, for generations to come. ¶Where do we begin? Action is the way. Commitment is the way. Implementation is the way. There should be an A-to-Z plan for Ganga: how the problem started, what the problem is, and how to take care of it. We must take care of it from all venues. ¶There are four kinds of pollution going into Ganga. Number one is the sewage, which is very important to handle. For sewage we are working with the government. But government alone is not enough. You need the people’s participation. To get the people’s participation you need leaders who can inspire people, who can bring them together to serve for the cause. That can be done by the spiritual leaders, the saints. Bringing the government and spiritual leaders together is being handled very carefully and successfully. ¶Number two is garbage being thrown in the Ganga. People think, “My home is my home, but the street, that’s not mine. My farm is mine, but the road is not mine. That’s the government’s road, the borough’s road, or the municipality’s road; it’s not mine.” But that is not correct. It’s not just “your home is your home.” The street is also yours. “My home, my street. My Ganga, my country.” Until we have this kind of relationship with the environment, that kind of awareness will not come. ¶Third is industrial pollution. That is a very challenging job. For that we are talking to industries. Some are nice; some are sometimes not so nice. For those we are going to the courts. We have done a few court cases, and as a result orders are given by the governments, and change is being implemented. ¶The fourth kind of pollution is religious pollution. People go on the banks of Ganga, use their flowers in worship and then throw into the Ganga their flowers and whatever plastic container they brought them in. They think Ganga can take care of it. We are stopping this. In the temples and in the ashrams, so much religious trash comes in the form of flowers. This is wonderful to offer to God but afterwards it has to be taken away. For that we have a flower van. It collects every week all those flowers—going from temple to temple, from ashram to ashram—and takes them to the field where they can make a fertilizer. All these forms of environmental degradation need to be handled simultaneously.

Insights from the Vedas & Ayurveda

VAMADEVA SHASTRI (DR. DAVID FRAWLEY)

THE UPANISHADS TEACH US THAT EVERYTHING IS BRAHMAN (“Sarvamkhalvidam Brahman”) or Satchidananda, Being-Consciousness-Bliss, differing by apparent names and forms only, not by essential nature. This does not mean that God created the world, but that God and the world are one as the manifest and unmanifest aspects of the same ocean of consciousness. All life is not merely interdependent but is one at its core with the Supreme Truth.

THE UPANISHADS TEACH US THAT EVERYTHING IS BRAHMAN (“Sarvamkhalvidam Brahman”) or Satchidananda, Being-Consciousness-Bliss, differing by apparent names and forms only, not by essential nature. This does not mean that God created the world, but that God and the world are one as the manifest and unmanifest aspects of the same ocean of consciousness. All life is not merely interdependent but is one at its core with the Supreme Truth.

The famous Bhumi Sukta, or Hymn to the Earth, of the Atharva Veda speaks of the mystical origin of the Earth in the meditations of the rishis: “Which in the beginning dwelled in the waters of the ocean, which the wise seers found by their magic wisdom power, the Earth whose heart is in the supreme ether, covered by truth and immortality—may that Earth grant us light and strength in the highest kingdom” (XII.1.8).

This Earth is meant as a place of worship and as a place to be worshiped, not merely as a playground for us to pursue our own personal gratification. This honoring of the Earth as an altar for inner and outer worship should be the basis of our relationships with the Earth and with the entire world.

This Vedic honoring of the sacred nature of all life is called yajna, sometimes translated as “sacrifice,” but which really refers to a sacred way of life and action that recognizes the divine presence in all things and strives to live in harmony with it. Our lives should be a ritual in which we strive to pursue a way of right action in harmony with the rhythms of nature and of the spirit through which nature works.

The practice of yoga arose as the inner sacrifice, or antaryaga, the offering of speech, breath and mind into the divine flame of awareness or Agni within our hearts. The yoga asana itself is meant to establish a sacred connection with the Earth. Yoga itself should be a sacred art of communing with all of life.

Ayurveda

Ayurveda warns of epidemic diseases, both physical and psychological in nature, that can arise through damage to our environment. The Charaka Samhita (III.6.23) discusses in detail disease-causing effects of polluted and disturbed air, water, land and seasons as a cause of destruction of entire countries. Twenty-eight factors of damage to air, water and land are listed, of which we can find all occurring in the world today. Besides harmful factors to the outer world, they include perverse and selfish behavior on the part of human beings, their fall from ethical behavior and disregard for spiritual practices, particularly unrighteous conduct by the rulers of a country and, above all, violence and war.

Charaka states that when natural time cycles like the seasons become disrupted, the situation becomes most dangerous. Yet he also states that such collective problems and diseases can be avoided and countered by health practices like pancha karma, by a sattvic life and the practices of yoga and meditation. Clearly our disruption of the environment has consequences both of a material and spiritual nature, though these may take some more decades to fully manifest, as nature works on a slower time cycle than human beings. We must reconnect ourselves with universal peace and once more come to honor the Earth and nature in order to solve this dire situation.