The Challenge of Ideas

1. Missionaries and colonists believe that their culture is superior to all other cultures.

2. Swami Vivekananda popularized the Hindu belief that all religions are valid paths to God.

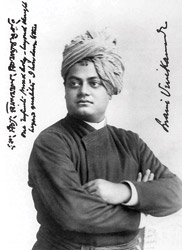

3. Gandhi’s satyagraha campaign brought independence to India and inspired nonviolent movements for freedom and civil rights around the world.

![]()

Key Terms

![]() HINDUISM TODAY’S Teaching Standards

HINDUISM TODAY’S Teaching Standards

5. Describe the conflict of ideas between prominent Hindus, including Vivekananda and Gandhi, and British missionaries and colonists.

6. Identify the influence of Swami Vivekananda on modern ideas of religious tolerance.

7. Explain how the Hindu principles behind satyagraha have improved the lives of people around the world.

If YOU lived then...

It is May 4, 1963, Birmingham, Alabama, USA. A thousand students from the city’s all-black high school join the nonviolent freedom protest led by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. to desegregate the city. Police knock them down using high-powered fire hoses and arrest hundreds. Your 17-year-old daughter is arrested and jailed for three days.

What do you say to her when she returns home?

BUILDING BACKGROUND: Dr. King went to India in 1959 to study Gandhi’s methods. He adopted satyagraha, calling it “nonviolent direct action.” King said it should so “dramatize an issue that it can no longer be ignored.” Gandhi translated satyagraha as “truth force” or “soul force.” Satyagraha, he taught, forbids inflicting violence on one’s opponent.

Understanding the Power of Ideas

In the 19th century, India was fighting the British in a war of ideas. One battle was over religion: Christian missionaries believed it was their sacred duty to convert all Indians. Another was over colonialism: the British were ruling India by military force, supported by the idea that they were a superior race. Many thinkers and activists, key among them Swami Vivekananda and Mahatma Gandhi, challenged these ideas. Today nearly all colonies have been freed. Few countries, if any, would claim a moral right to colonize another. But religious conflict remains a crucial issue. Vivekananda’s teaching of equal respect for all religions is more relevant today than ever before.

A Young Monk with a Message of Tolerance

The story of Swami Vivekananda (1863–1902) starts with a temple priest named Sri Ramakrishna (1836-1886) who lived near Calcutta. He was a mystic, a person who had visions of God and many profound spiritual experiences. Though not formally educated, he attracted followers from the city’s prominent families. One was an 18-year-old college student named Narendranath Dutta.

When they first met, Narendra asked Ramakrishna why he believed in God. Ramakrishna replied, “Because I see Him just as I see you here, only in a much more intense sense.” Narendra took Ramakrishna as his guru and was trained by him for the next five years.

SWAMI VIVEKANANDA’S ADDRESS TO THE PARLIAMENT OF THE WORLD’S RELIGIONS

On September 11, 1893, Swami Vivekananda began his address with the words, “sisters and brothers of America,” resulting in a two-minute standing ovation. He continued, “It fills my heart with joy unspeakable to rise in response to the warm and cordial welcome which you have given us. I thank you in the name of the millions and millions of Hindu people of all classes and sects.

“I am proud to belong to a religion which has taught the world both tolerance and universal acceptance. We believe not only in universal toleration, but we accept all religions to be true. I am proud to belong to a nation which has sheltered the persecuted and the refugees of all religions and all nations of the earth.

“I will quote to you, brethren, a few lines from a hymn which I remember to have repeated from my earliest boyhood, which is every day repeated by millions of human beings: ‛As the different streams, having their sources in diff erent places, all mingle their water in the sea, O Lord, so the different paths which men take through diff erent tendencies, various though they appear, crooked or straight, all lead to Thee.’

“Sectarianism, bigotry and its horrible descendant, fanaticism, have possessed long this beautiful earth. It has filled the earth with violence, drenched it often with human blood, destroyed civilization and sent whole nations to despair. Had it not been for this horrible demon, human society would be far more advanced than it is now.

“But its time has come, and I fervently hope that the bell that tolled this morning in honor of this convention will be the deathknell to all persecutions with the sword or the pen, and to all uncharitable feelings between persons wending their way to the same goal.”

After Ramakrishna’s death, Narendra took vows as a Hindu monk, becoming Swami Vivekananda. He gave up his further education and instead set off on pilgrimage across India. He deeply impressed many people in Madras. They raised money door to door to pay for his travel to America for the 1893 Parliament of the World’s Religions.

At that interfaith congress in Chicago, the cultured and eloquent 30-year-old swami was well received. In his opening talk, he declared, “We believe not only in universal toleration, but we accept all religions to be true.” The popularity of this Hindu message of respect and tolerance alarmed some Christian participants who had hoped the Parliament would prove their religion superior to others.

The New York Herald reported at the time, “Vivekananda is undoubtedly the greatest figure in the Parliament of Religions. After hearing him, we feel how foolish it is to send missionaries to this learned nation.” Another reporter wrote, “The impertinence of sending half-educated theological students to instruct the wise and erudite Orientals was never brought home to an English-speaking audience more forcibly.”

Vivekananda returned to India a hero. He aroused a new pride among Hindus and kindled in India’s youth a nationalist spirit. Vivekananda founded the Ramakrishna Mission as a religious and educational institution to address India’s social problems. He died on July 4, 1902, at age 39. Freedom fighter Subhash Chandra Bose aptly called Swami “the maker of modern India.”

Vivekananda was not the first Indian religious and social reformer of the 19th century. Raja Ram Mohan Roy sought to counter the criticisms of Hinduism made by the British missionaries. He founded the Brahmo Samaj in 1828 as a new religion with Christian-style services. Swami Dayananda Saraswati was a Hindu traditionalist. He began the Arya Samaj in 1875 to revive Vedic society and religion. He believed Hinduism could be purified by a return to the teachings and practices of the Vedas. Both the Brahmo Samaj and Arya Samaj encouraged Indians to be egalitarian and do more social service for the poor.

Vivekananda, on the other hand, had a powerful impact both on India and the West. In particular, he introduced the Hindu idea that all religions deserve respect as valid paths to God, an idea now firmly established in America. In 2008, polls found that while 76% of Americans identify themselves as Christian, 65% believe that “many paths other than my own can lead to eternal life.” How different from Vivekananda’s time, when most Americans were staunch Christians who believed theirs was the only way to God!

Satyagraha: Fighting without Violence

Mahatma Gandhi was a devout Hindu, a skilled lawyer and a master politician. His strategy to gain India’s freedom was satyagraha, “truth force,” the application of righteous and moral force in politics. Satyagraha is based on Hindu principles, including nonviolence, the ultimate goodness of the soul and a belief in the existence of God everywhere and in everyone. Satyagraha requires a core group of self-sacrificing and disciplined activists. To be successful, it must have widespread publicity, generating national concern and international pressure.

Since Gandhi’s time, satyagraha has been used to win civil rights for blacks in America, improve conditions for California farm workers, end apartheid in South Africa and publicize human rights abuses in Myanmar.

Gandhi used the power of satyagraha to oppose the British salt tax to tighten its stranglehold on India’s economy. The Raj imposed strict controls on salt production and a stiff tax on its sale. People could be arrested for making or selling salt. This callous tax on a basic necessity of life especially burdened the poor. To Gandhi, the salt tax symbolized the tyranny of the Raj.

Gandhi’s dramatic revolt, the Salt March, began on March 12, 1930. Tens of thousands of people cheered as he walked 390 kilometers from his Sabarmati Ashram in Ahmedabad, Gujarat, to Dandi Beach. After morning prayers on April 6, he collected salt on the seashore and proclaimed, “With this, I am shaking the foundations of the British Empire.” Hearing this, people all across India freely collected and sold salt. Tens of thousands were arrested, including 18,000 women. The march was closely covered by the international press, making Gandhi famous in Europe and America.

Six weeks later, hundreds of marchers attempted to take over the Dharasana Saltworks, 300 kilometers north of Bombay. The ensuing clash was reported worldwide by Webb Miller of United Press International: “Police charged [the marchers], swinging their clubs and belaboring the raiders on all sides. The volunteers made no resistance. As the police swung hastily with their sticks, the natives simply dropped in their tracks. Less than 100 yards away I could hear the dull impact of clubs against bodies. The watching crowds gasped, or sometimes cheered, as the volunteers crumpled before the police without even raising their arms to ward off the blows.”

Professor Richard Johnson wrote, “It is widely believed that the Salt Campaign turned the tide in India. All the violence was committed by the British and their Indian soldiers. The legitimacy of the Raj was never reestablished for the majority of Indians and an ever increasing number of British subjects.” The independence struggle was now truly a mass movement.

In a similar way, in 1963 Martin Luther King forced the desegregation of Birmingham, Alabama. Civil rights activists were arrested by the hundreds as they attempted to peacefully integrate the city’s restaurants, shops and churches. Violent attacks by police on unarmed, nonresisting marchers attracted worldwide attention. The United States was shamed and embarrassed as a result. New laws were soon passed requiring equal rights for all.

The Colonized Mind

The nonviolent strategies of satyagraha helped Indians and black Americans attain freedom after centuries of domination. But decades later, they and their descendants still felt inferior to white people. This condition, called “the colonized mind,” can persist long after physical freedom is won.

Many of India’s colonized people, especially those educated in English schools, came to believe that everything about themselves was inferior to that of the British. Thus they considered English superior to any Indian language, English manners better than Indian manners, a suit and tie better than a kurta shirt and pants, and white skin better than brown skin.

Overcoming, or “decolonizing,” the colonized mind requires a multicultural education, self-examination and rejection of externally created ideas of inferiority. The colonized mind is the most lasting negative impact of colonialism.

REVIEWING IDEAS, TERMS AND PEOPLE

1. Describe: What did British missionaries and colonists believe about their culture compared to Indian culture?

2. Interpret: How did American journalists react to Swami Vivekananda’s speech at the 1893 Chicago Parliament?

3. Identify: Where has Gandhi’s strategy of satyagraha been used outside of India?

4. Explain: How did nonviolent protests “turn the tide” for Indian freedom and the American civil rights movement?

5. What Hindu ideals were promoted by Swami Vivekananda and Gandhi? How have they influenced today’s world?

![]()

In accepting the 2009 Nobel Peace Prize, President Obama said, “As someone who stands here as a direct consequence of Dr. King’s life work, I am living testimony to the moral force of non-violence. I know there’s nothing weak, nothing passive, nothing naive in the creed and lives of Gandhi and King.”

ACADEMIC VOCABULARY

desegregate

allow equal access to public places for all races

pilgrimage

to travel to a sacred place for worship

eloquent

pleasant, fluent, convincing in speech

impertinence

lack of respect, rudeness

theological

having to do with the study of religious concepts

erudite

scholarly; having great learning

egalitarian

the principle that all people deserve equal rights and opportunities

callous

lacking mercy

tyranny

cruel and unjust use of power or authority

belabor

to beat severely

civil rights

political and social freedom and equality

integrate

to end the separation of people by race

naive

innocent; lacking experience