Family Life and Monastic Life

The Spiritual Ideals of Hinduism’s Two Noble Paths of Dharma

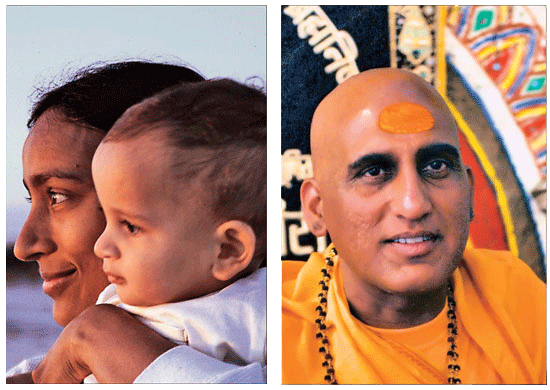

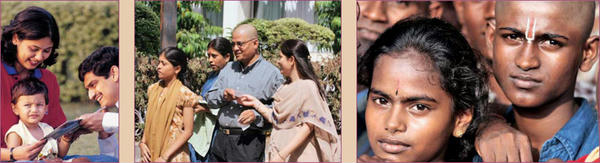

Exemplars of dharma’s two paths: writer and homemaker Vatsala Sperling of Vermont, USA, with her son Mahar; respected leader of Juna Akhara, Acharya Avdheshananda Ji

N HINDUISM THERE HAS ALWAYS been a choice of paths to follow—grihastha or sannyasa, family or monk. Unfortunately, in modern Hinduism the distinction between the two has become muddled, both in the minds of Hindus themselves as well as in textbooks and other writings that present Hinduism to the non-Hindu world. ¶Hinduism’s purusharthas, four goals of life, are a useful reference for understanding the distinction between the two paths. The four goals are 1) dharma, or piety; 2) artha, or wealth; 3) kama, or pleasure; and 4) moksha, or liberation. Those on the grihastha path pursue all four goals, and the way they do so changes according to their age or ashrama in life. Those on the sannyasa path renounce artha, kama and family dharma in one-pointed pursuit of moksha—liberation from rebirth on Earth through intense personal experience of God. ¶For the grihastha, in the first ashrama, brahmacharya, age 12-24, the primary focus is on studying at school and preparing for profession and married life. In the second ashrama, grihastha, age 24-48, the primary focus is raising a family and fulfilling a career. The third ashrama, vanaprastha, age 48-72, is a time of transition from family and career to one of elder advisor to the younger generation. The fourth ashrama, sannyasa, age 72 onward, is a time in which the primary focus is on moksha, meaning that religious practices are the main activity of one’s day. The sannyasin directly enters the fourth ashrama at the time of his initiation, no matter what his age, skipping over the other phases of life. ¶One of the most common ways the two paths have been muddled in modern Hinduism is in the classic textbook notion that Hindus believe the world is unreal and that this is why there is so much poverty in India. This, of course, is an incorrect perception. The accurate statement is that those on the path of the monk are trained to look at the world as impermanent, or unreal or fleeting. Grihasthas, however are not. They pursue the same ideals of success, family and wealth as do families in Western society. ¶Many thoughtful Hindu lay leaders lament the lack of trained Hindus who can speak out in a knowledgeable way about Hinduism. One trend is to train Hindu priests for this capacity, which in the Western world is called a minister. Said another way, Hinduism needs more ministers to TEACH and counsel. Of course, this is one of the roles that Hindu monks traditionally fulfill. Thus, another solution is to produce and train more swamis and sadhus to serve as competent ministers. ¶This 16-page Educational Insight is drawn primarily from Gurudeva’s Master Course trilogy (www.gurudeva.org/resources/books/).

N HINDUISM THERE HAS ALWAYS been a choice of paths to follow—grihastha or sannyasa, family or monk. Unfortunately, in modern Hinduism the distinction between the two has become muddled, both in the minds of Hindus themselves as well as in textbooks and other writings that present Hinduism to the non-Hindu world. ¶Hinduism’s purusharthas, four goals of life, are a useful reference for understanding the distinction between the two paths. The four goals are 1) dharma, or piety; 2) artha, or wealth; 3) kama, or pleasure; and 4) moksha, or liberation. Those on the grihastha path pursue all four goals, and the way they do so changes according to their age or ashrama in life. Those on the sannyasa path renounce artha, kama and family dharma in one-pointed pursuit of moksha—liberation from rebirth on Earth through intense personal experience of God. ¶For the grihastha, in the first ashrama, brahmacharya, age 12-24, the primary focus is on studying at school and preparing for profession and married life. In the second ashrama, grihastha, age 24-48, the primary focus is raising a family and fulfilling a career. The third ashrama, vanaprastha, age 48-72, is a time of transition from family and career to one of elder advisor to the younger generation. The fourth ashrama, sannyasa, age 72 onward, is a time in which the primary focus is on moksha, meaning that religious practices are the main activity of one’s day. The sannyasin directly enters the fourth ashrama at the time of his initiation, no matter what his age, skipping over the other phases of life. ¶One of the most common ways the two paths have been muddled in modern Hinduism is in the classic textbook notion that Hindus believe the world is unreal and that this is why there is so much poverty in India. This, of course, is an incorrect perception. The accurate statement is that those on the path of the monk are trained to look at the world as impermanent, or unreal or fleeting. Grihasthas, however are not. They pursue the same ideals of success, family and wealth as do families in Western society. ¶Many thoughtful Hindu lay leaders lament the lack of trained Hindus who can speak out in a knowledgeable way about Hinduism. One trend is to train Hindu priests for this capacity, which in the Western world is called a minister. Said another way, Hinduism needs more ministers to TEACH and counsel. Of course, this is one of the roles that Hindu monks traditionally fulfill. Thus, another solution is to produce and train more swamis and sadhus to serve as competent ministers. ¶This 16-page Educational Insight is drawn primarily from Gurudeva’s Master Course trilogy (www.gurudeva.org/resources/books/).

The Two Paths of Dharma

________________

From the Sacred Teachings of Satguru Sivaya Subramuniyaswami

________________

here are two traditional paths for the devout Hindu of nearly every lineage. The first is the path of the renunciate. The second is the path of the householder, who guides human society and produces the next generation. The ancient rishis evolved well-defined principles for both, knowing that unmarried aspirants would most easily unfold by adhering to principles of nonownership, noninvolvement in the world and brahmacharya (celibacy), while married men and women would uphold the more complex and material family dharma. Though the principles or guidelines for these two paths are different, the goal is the same: to establish a life dedicated to spiritual unfoldment, hastening the evolution of the soul through knowledge of the forces at work within us, and wise, consistent application of that knowledge.

here are two traditional paths for the devout Hindu of nearly every lineage. The first is the path of the renunciate. The second is the path of the householder, who guides human society and produces the next generation. The ancient rishis evolved well-defined principles for both, knowing that unmarried aspirants would most easily unfold by adhering to principles of nonownership, noninvolvement in the world and brahmacharya (celibacy), while married men and women would uphold the more complex and material family dharma. Though the principles or guidelines for these two paths are different, the goal is the same: to establish a life dedicated to spiritual unfoldment, hastening the evolution of the soul through knowledge of the forces at work within us, and wise, consistent application of that knowledge.

THE PATH OF RENUNCIATION

The two fundamental objectives of sannyasa, renunciation, are to promote the spiritual progress of the individual, bringing him into God Realization, and to protect and perpetuate the religion. Sannyasa life has both an individual and a universal objective. At the individual level, it is a life of selflessness in which the sannyasin has made the supreme sacrifice of renouncing all personal ambition, all involvement in worldly matters, that he might direct his consciousness and energies fully toward God. Guided by the satguru along the sadhana marga, he unfolds through the years into deeper and deeper realizations. Ultimately, if he persists, he comes into direct knowing of transcendent Reality. At the universal level, the sannyasins foster the entire religion by preserving the truths of the Sanatana Dharma. Competent swamis are the teachers, the theologians, the exemplars of their faith, the torchbearers lighting the way for all.

Among those on the renunciate path, there are two lifestyles. In our Holy Orders of Sannyasa, these two lifestyles are described as follows. “Some among them are sadhus, anchorites living in the seclusion of distant caves and remote forests or wandering as homeless mendicants, itinerant pilgrims to the holy sanctuaries of Hinduism. Others dwell as cenobites, assembled with their brothers, often in the ashrama, aadheenam or matha of their satguru, but always under the guru’s aegis, serving together in fulfillment of a common mission. These devotees, when initiated into the order of sannyasa, don the saffron robes and thereby bind themselves to a universal body of Hindu renunciates, numbering today three million, whose existence has never ceased, an assembly of men inwardly linked in their mutual dedication to God, though not necessarily outwardly associated.”

There are three primary currents in the human nerve system. The aggressive-intellectual current is masculine, mental in nature and psychically seen as blue in color. This current is termed in Sanskrit pingala. The passive-physical current is feminine, material in nature. This current, which is pink or red, is known as ida. The third current is spiritual in nature and flows directly through the spine and into the head. Being yellowish-white, the sushumna, as it is called, is the channel for pure spiritual energies that flood into the body through the spine and out into the 6,000 miles of nerve currents. Depending on the nature and dharma, each individual’s energy expresses itself as predominantly physical or intellectual—passive or aggressive—or spiritual. However, in the sannyasin the two forces are so precisely balanced that neither is dominant, and he therefore lives almost totally in sushumna. The monastic, whether a monk or a nun, is in a sense neither male nor female, but a being capable of all modes of expression.

Brahmacharya for the monastic means complete sexual abstinence and is, of course, an understood requirement to maintain this position in life. Transmutation of the sexual energies is an essential discipline for the monastic. Transmutation is not a repression or inhibition of natural instincts, but a conscious transformation of these energies into life-giving forces that lend vigor and strength to the body and provide the impetus that propels awareness to the depths of contemplation. This process of transmutation begins with the sexual instincts but encompasses transmutation of all instinctive forces, including fear, anger, covetousness, jealousy, envy, pride, etc. True purity is possible only when these base instincts have been conquered.

The renunciate fosters the inner attitude, strictly maintained, that all young women are his sisters and all older women his mother. He does not view movies that depict the base instincts of man, nor look at books, magazines or websites of this nature. The principle with which he is working is to protect the mind’s natural purity, not allowing anything that is degrading, sensuous or low-minded to enter into the field of his experience.

At times, the renunciate’s sadhana is austere, as he burns layer after layer of dross through severe tapas. He wears the saffron robe, studies the ancient ways and scriptures. He chants the sacred mantras. He reflects constantly on the Absolute. He lives from moment to moment, day to day. He is always available, present, open. He has neither likes nor dislikes, but clear perceptions.

Having stepped out of his ego shell, the sannyasin is a free soul. Nothing binds him. Nothing claims him. Nothing involves him. Without exclusive territory, without limiting relationships, he is free to be himself totally. If he has problems within himself, he keeps them silently within and works them out there. If he speaks, it is only to say what is true, kind, helpful or necessary. He never argues, debates, complains. His words and his life always affirm, never negate. He finds points of agreement, forsaking contention and difference. No man is his enemy. No man is his friend. All men are his teachers. Some teach him what to do; others teach him what not to do. He has no one to rely upon except God, Gods, guru and the power within his own spine. He is strong, yet gentle. He is aloof, yet present. He is enlightened, yet ordinary. He speaks wisely of the Vedic scriptures and ancient shastras and lives them in his own example. Yet, he consciously remains inconspicuous, transparent.

He is a man on the path of enlightenment who has arrived at a certain subsuperconscious [intuitive] state and wishes to stay there. Therefore, he automatically has released various interactions with the world, physically and emotionally, and remains poised in a contemplative, monastic lifestyle. The basic thought behind the philosophy of being a sannyasin is to put oneself in a hot-house condition of self-imposed discipline, where unfoldment of the spirit can be catalyzed at a greater intensity than in family life, where the exterior concerns and overt responsibilities of the world predominate.

The sannyasin is the homeless one who remains detached from all forms of involvement—friends, family, personal ambition—finding security in his own being rather than attaching himself to outward manifestations of security, warmth and companionship. He is alone, but never lonely. He lives as though on the eve of his departure, often abiding no more than three nights in the same place. He may be a pilgrim, a wandering sadhu. He may be a monastic contemplative living in a cloistered monastery or semi-cloistered ashrama.

In preparation for sannyasa, the aspirant leaves behind family, former friends and old acquaintances and steps out into a new pattern of subsuperconscious living. He strives to be all spine-power, all light. When we see him trying, although he may not be too successful at it if he is going through some inner turmoil or challenge, we know he is striving, and that is an inspiration to us. His very existence is his mission in life. He has dedicated himself to live a life of total commitment to the path of yoga, and by doing so he sustains the spiritual vibration for the householders. It is the renunciate who keeps the Vedic religions alive on the Earth. He keeps the philosophy vibrant and lucid, presenting it dynamically to the householders.

Monks of every Hindu order are guided and guarded by unseen beings who look after their lives as if they were their own. Families are blessed who share in and support the renunciation of their sons born through them to perform a greater dharma than the grihastha life could ever offer. It is the monastic communities worldwide, of all religions, that sustain sanity on this planet. It is the monks living up to their vows who sustain the vibration of law and order in the communities and nations of the world. This is how the devonic [angelic] world sees each monastic community worldwide. This is how it is and should always be. This is how humanity balances out its experiential karmas and avoids destroying itself as it passes through the darkness of the Kali Yuga. The monastic communities that surround the planet, fulfilling their dharma, compensate for the adharma that is so prevalent, thus ensuring that humanity does not self-destruct in these trying times. We must, for the sake of clarity, state here that monastic communities are either strictly male or strictly female. Coed mixed-group ashramas are not monastic communities, but classed traditionally as communes.

Path-Choosing

The two paths—householder and renunciate—every young man has to choose between them. In Hindu tradition the choice is made before the marriage ceremony, and, if not, during the ceremony itself. Though guided by the advice of parents, elder family members and religious leaders, the choice is his and his alone as to how his soul is to live through the birth karmas of this incarnation. Both paths take courage, great courage, to step forward and embrace the responsibilities of adult life.

In making this decision in our tradition we have found it valuable for the young man to spend time in a Hindu monastery where he can live the monk’s life for a period of six months or more and receive spiritual and religious training that will enhance his character for a positive future, no matter which path he chooses. Only by living for a time as a monk will he come to truly understand the monastic path and be empowered to make a knowledgeable choice between that path and the traditional dharma of the householder, raising a family and serving the community. One of the best times for this sojourn apart from the world, setting aside life’s usual concerns, is just after high school or during an interim break. Then, after the time in the monastery, a firm and positive consideration should be made, in consultation with family and elders, as to which of the two paths he wishes to pursue.

Path-choosing is a beginning, pointing a direction, declaring an intention. Marriage becomes a lifetime commitment only when the final marriage vows are spoken. This is preceded by months or even years of choosing a spouse, a process that calls forth the wisdom of the two families, community elders, religious leaders and those who are trained to judge astrological compatibilities. Renunciate life in our Natha tradition and many others becomes a lifetime commitment only when final, lifetime vows of renunciation of the world are voiced. In some lineages, no formal vows are even taken, but there are traditionally understood norms of conduct, proprieties and protocol to be adhered to.

We might say that one does not choose renunciation, but rather is chosen by it, when the soul is matured to the point when the world no longer holds a binding fascination. While considerations of the order that one will join are practical realities, it is vital that the young man choosing renunciate life does so not seeking place or position in a particular order, but sets out as a free spirit, unencumbered, under the guidance of his satguru, willing to serve everywhere and anywhere he is sent, be it in his guru’s central ashrama, a distant center, a monastery of another guru or alone on an independent sadhana. The clear path is to define the path itself. Then, proceed with confidence.

Know it with a certainty beyond question that the path of renunciation is life’s most grand and glorious path, and the singular path for those seeking life’s ultimate goal, Realization of God as timeless, formless, spaceless Absolute Reality, that mystic treasure reserved for the renunciate. Know, too, that renunciation is not merely an attitude, a mental posture which can be equally assumed by the householder and the renunciate. Our scriptures proclaim that a false concept. My order supports the scriptural doctrine that the two paths—householder and renunciate—are distinct in their dharmas and attainments, affirming that true renunciation may not be achieved by those in the world even by virtue of a genuine attitude of detachment. The householder may attain great and profound spiritual depths during his life, unfolding the mysteries of existence in his or her states of contemplation and, according to our ancient mystics, perhaps experiencing total God Realization at the hour of death, though this attainment is reserved for the ardent, sincere and devout grihasthi. Many years ago, my satguru, Yogaswami of Jaffna, Sri Lanka, wrote the following poem to honor those valiant souls on the path of renunciation.

Hail, O sannyasin, love’s embodiment!

Does any power exist apart from love?

Diffuse thyself throughout the happy world.

Let painful maya cease and ne’er return!

Day and night give praise unto the Lord.

Pour forth a stream of songs to melt the very stones.

Attain the sight where night is not nor day.

See Siva everywhere, and rest in bliss.

Live without interest in worldly gain.

Here, as thou hast ever been, remain.

Then never will cruel sorrow venture nigh.

Best of sannyasins, of one-pointed mind!

Morning and evening worship without fail

The holy feet of the Almighty Lord,

Who here and hereafter preserves and safeguards thee.

Cast aside the fetters of thy sins!

By steadfast concentration of thy mind

Awareness of a separate self thou must extirpate.

Conquer with love all those that censure thee.

Thou art eternal! Have no doubt of this!

What is not thou is fancy’s artifice.

Formless thou art!

Then live from all thought free!

Voices on Hindu Family Life

EADERS OF THE UNITED NATIONS DEDICATED 1994 AS THE international Year of the Family. They were seeking to counter a global failure of the family unit and the by-products of such a breakdown: crime, delinquent youth, disobedient children, divorce and other household miseries, in other words the basic problems of social instability. They decided to inquire of the major religions of the world as to what their views were and are today on family life, all planned for a multi-lingual United Nations publication, Family Issues as Seen by Different Religions, a unique vision of family from the point of view of Jews, Christians, Muslims, Buddhists, Hindus and Baha’is. The UN approached us at HINDUISM TODAY magazine to define and describe the traditional family values of the Hindu. In creating the Hindu chapter for the UN book, we joined forces with two of our HINDUISM TODAY correspondents, Archana Dongre of Los Angeles and Lavina Melwani of New York. Their comments provide the “voices” of experience throughout the text. We include excerpts from the resulting article here as a sidebar to this Educational Insight on the two paths of Hindu dharma.

EADERS OF THE UNITED NATIONS DEDICATED 1994 AS THE international Year of the Family. They were seeking to counter a global failure of the family unit and the by-products of such a breakdown: crime, delinquent youth, disobedient children, divorce and other household miseries, in other words the basic problems of social instability. They decided to inquire of the major religions of the world as to what their views were and are today on family life, all planned for a multi-lingual United Nations publication, Family Issues as Seen by Different Religions, a unique vision of family from the point of view of Jews, Christians, Muslims, Buddhists, Hindus and Baha’is. The UN approached us at HINDUISM TODAY magazine to define and describe the traditional family values of the Hindu. In creating the Hindu chapter for the UN book, we joined forces with two of our HINDUISM TODAY correspondents, Archana Dongre of Los Angeles and Lavina Melwani of New York. Their comments provide the “voices” of experience throughout the text. We include excerpts from the resulting article here as a sidebar to this Educational Insight on the two paths of Hindu dharma.

THE HINDU VIEW OF FAMILY

Hindu families all over the world are struggling—some failing, most succeeding. Our experience is that those most rooted in their Hinduness cope better and are the better survivors. Hindu households, sheltering one-sixth of the human race, are being threatened. What if the concept of family itself were dying? What if the very institution, the cauldron of our cultural and spiritual consciousness, were struck by some fatal disease and perished? Who could measure such a tragedy? Who could weep sufficient tears? Yet, that is precisely the path which we are semi-consciously following, a path leading to the demise of the traditional Hindu family, the source of our strength, the patron of our spirituality, the sole guarantor of our future.

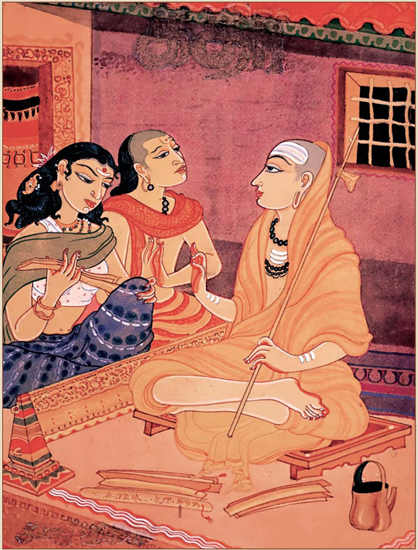

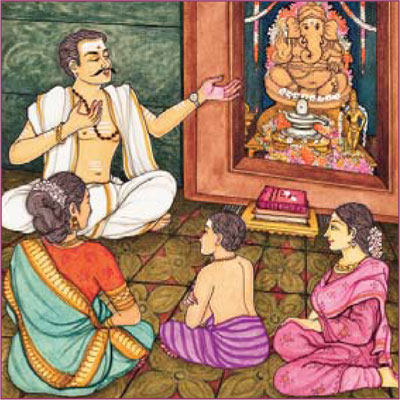

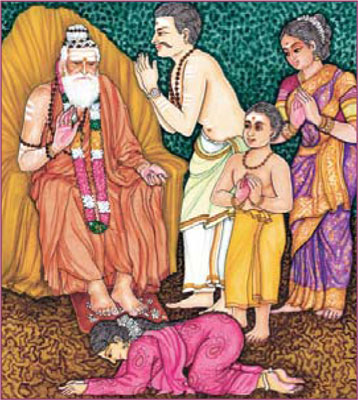

In a scene from olden days in India, a priest and his wife sit before a sannyasin to receive his blessings. They present to him a difficulty they face, and he gives advice from tradition.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

Is it our fault that the family is disintegrating? Perhaps. Does it portend uncertainty? Be certain that it does. Is it inevitable? Probably not. A final eulogy for the Hindu family may be premature. With that in mind, let us embark on an exploration of some of the Hindu family’s truly remarkable strengths.

VOICES: My grandma never tired of reminding us that the Hindu religion always glorified sacrifice. It was considered heroic to make sacrifice for the family members. Hindu epics like Ramayana and Mahabharata purport that even great beings like Lord Rama and noble kings like the Pandavas had to endure trying circumstances and make sacrifices. “So what’s wrong if ordinary folks had to make some sacrifices?” she would say. Parents often make great sacrifices to give a good education to their children. Many Hindu parents have gone hungry to afford quality education for their children. The children in turn curtail their freedom and luxury when parents grow old and infirm and need support from the younger generation. A Hindu never pities a sacrifice, but glorifies it with appreciation. Grandma made a big point to us about hospitality. She took it as a spiritual duty to serve guests as if they were God. This helped a lot in tying her community together and gave the family a loving way to greet the outside world. If a guest comes to a family, even unannounced, he is invited in warmly and asked about his well being. He is also served the best food in the house, even to the extent that family members may go hungry to ensure that the guest is well fed. Hinduism taught us the love of all living creatures. At lunch time, my mother would say a silent prayer and set aside a portion to be fed to the cows. If a hungry man came to the door at mealtime, he was fed and given a few coins.

OUR CENTER GALLERY ALTERNATELY FEATURES SCENES OF HOUSEHOLDERS AND RENUNCIATES ENGAGED IN WORSHIP, SERVICE, FELLOWSHIP AND LIFE’S MANY JOYS

Scenes from Family Life

When family life possesses love and virtue, it has found both its essence and fruition. TIRUKURAL, VERSE 5

A mother applies a forehead mark for her daughter during puja; a beautifully adorned woman outshines the roses in a Singapore garden; a youth carries kavadi during festival time at Nallur Temple in Sri Lanka; children in Nepal offer lamps during the Chaith festival; a Jaffna-born couple marry in London; a royal priest pours sandalwood paste over a crystal Sivalinga during puja

VOICES: Growing up a Hindu in India, I found that pleasure and pilgrimage, religious rituals and daily life were intricately intertwined. Religion was always associated with joy and pleasure, never moralistic teaching. Every weekend we were taken to the beautiful sandstone Birla Mandir—cold marble below bare feet, the softness of the marigolds and rose petals in our hands, the smiling faces of Krishna, Siva and Vishnu, the harmonium and cymbals and the sheer faith of hundreds of devotees. Afterwards, there were joy rides in the temple complex, trinkets and holy pictures and a cold soda. For us, it was a spiritual Disney World.

VOICES: Where I grew up, mothers ruled the house, even though they did not go out in the olden days to earn. Sisters were respected and given gifts on at least two religious occasions. The rituals like Raksha Bandhan and Bhau Bij are woven around pure love between a brother and a sister and bonding of that relationship. In the former, the sister ties a specially made bracelet around her brother’s wrist, requesting him to protect her if need be, and in the latter, the sister does arati (a worshipful expression of love and devotion through a tiny lighted ghee lamp) to her brother, wishing him long life and prosperity. The brother gives her gifts and sweets on both occasions. The Hindu religious principles emphasize that women should be respected. A Sanskrit saying goes, “Yatra naryastu pujyante, ramante tatra devatah.” It means that wherever the women are honored, those are the places where even the Gods rejoice.

How is the Hindu concept of family experienced differently from that of other faiths? Only in the faiths of India does one encounter the tenet that we all experience a multitude of families in our journey toward God. In birth after birth we evolve, our tradition assures. In family after family we grow and mature and learn. Thus, in the Hindu family we find that the past and the future are intricately bound together. How intricately? We know a Sri Lankan family who is certain that their daughter, now nine, is the father’s deceased grandmother. In this community it is considered a very great blessing—especially if one has the privilege of being part of a fine, noble family—for a departed relative to be born again into its midst. There is a profound intuition that when relatives pass they will return, perhaps soon and perhaps in the very same home. So, everyone watches for the telltale signs. How wonderful, the family feels, to care for Grandma as she once cared for us!

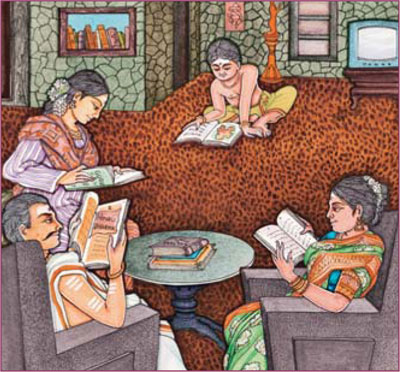

A family study teachings of their lineage

Thus, the spiritual insight into rebirth extends the family concept beyond the present, binding the present to the past, and promising further continuity with the future. Many Hindu families are aware of such relationships. Many others will consciously seek to be born into a particular family, knowing that life there will be fulfilling, secure and high-minded.

VOICES: When a married daughter visits her parents’ family, she is revered like a guest but showered with love like a daughter, with blessings and all the nice clothes as well as food the family can give. I had such a wonderful homecoming in India after I had lived for many years in the West. Such a homecoming of a few days is an emotionally gratifying, soul-satisfying event for the girl, who carries those fond memories for life.

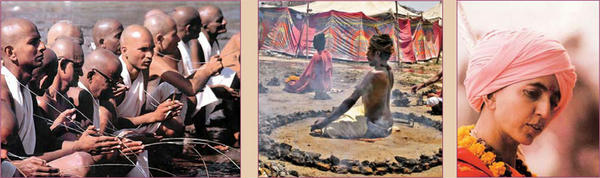

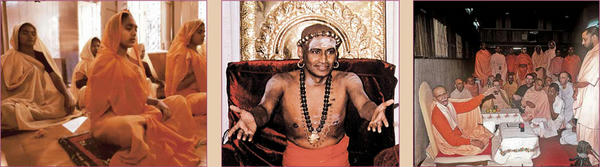

Scenes from Renunciate Life

Attempting to speak of the renunciate’s magnitude is like numbering all the human multitudes who have ever died. TIRUKURAL, VERSE 22

An ash-covered sadhu in prayer; Pramukh Swami, head of BAPS, initiating a new sadhu in Bhuj; Swami Tejomayananda with devotees; sadhus sit for a simple meal served on banana leaves; a score of men during initiatory rites in Ujjain to enter the Avahan Akhara; two Vaishnava yogis perform fire tapas, encircled by burning coals; a holy woman of Juna Akhara at the Ujjain Kumbha Mela

Hinduism teaches a constellation of principles which, if followed by husband and wife, make the bold assertion that preserving the marriage and the integrity of the family holds rewards that far outweigh benefits they might expect from separation. We work with families on a daily basis, solving their problems, helping them to individually follow their path and to mutually work together. Hinduism teaches them the ideals of dharma, which includes duty, selflessness, virtue and faith. When dharma is the shared ideal of every family member—as opposed to self-fulfillment or social-economic objectives—it is easier to navigate troubled waters, easier to persist in seasons of loss or lack, in times of emotional or mental difficulty.

Leaving her body at death, a soul is received by devas

VOICES: Looking back to my early years, it was the scriptures that tied our family together. I would hear father and grandfather chanting the Vedic mantras together in the early hours of each day. Everyone I know held the highest esteem for the Vedas, the very voice of God, elders would say. I knew they were old, and everyone said they were profound. But it was not until I was in my teens that I really discovered the Upanishads. Such beauty, such profundity, such humor and insight I had never before or since known. I would spend hours with the texts, talking with my parents and friends, wondering myself how these men, so many thousands of years ago, had gained all that wisdom—more, it seemed to me then, than people had today. Through the years I have seen so many families whose lives revolve around the sacred texts. While all honor the Vedas, for some the heart is moved by the Gita, the epics, the Tirumurai or maybe their own family guru’s writings composed only decades ago. Whatever texts they are, it’s quite clear in my experience that sacred texts do much to bind a family together in thought.

Then there is faith in karma. The Hindu family believes, in its heart, that even life’s difficulties are part of God’s purpose and the fruition of each member’s past karmas. To go through things together is natural, expected, accepted. Breaking up, divorcing, separating—such reactions to stress don’t resolve karmas that were brought into this life to go through. In fact, they make things worse, create new, unseemly karmas and thus further need for perhaps even more sorrowful births. The belief in karma—the law by which our thoughts, words and deeds reap their natural reactions—helps hold a family together, not unlike the crew of a storm-tossed ship would never think of jumping overboard when the going gets rough, but work together to weather the crisis, with their shared goal lying beyond the immediate difficulty.

Thus, difficult experiences can be serenely endured by the practicing Hindu. Knowing this in her heart, a Hindu wife in Kuala Lumpur can find solace in the midst of the death of a child. Knowing this in his heart, a Hindu father in Bangalore can sustain periods of privation and business failure. Each finds the strength to go on.

VOICES: There is a beautiful word in the Hindi language, shukur, which means acceptance. Sometimes it’s very hard to accept the cards life deals one, yet the Hindu belief in the acceptance of God’s will makes it possible to bear incredible hardships. A young friend of my husband went into a coma after going in for preventive surgery. They gave him too much chloroform, and he never came out of the coma. He was a young man, his children were young. In the beginning, his wife was frantic, weeping all the time. Yet, her beliefs were solid as a rock within her, gradually calming her. It’s now five years later, and she’s picked up the pieces of her life. Yet she never forgets to have her pujas; her husband’s picture is always there in the ritual ceremonies. His presence is there in the family. She seems to know that the soul cannot die, that his spirit lives on. Every year on his death anniversary, we all gather for the ritual ceremonies. Everybody feels the grief, and each religion teaches you to cope in a different way. Her belief in the undying soul gives her a little solace. She constantly has the prayers and the satsangas at home, and they help her in the changing patterns of her life.

Scenes from Family Life

The virtuous householder supports the needs of renunciates, ancestors and the poor. TIRUKURAL, VERSE 41

Father and daughter arrive at a temple in Sri Lanka; women pray at a shrine in Ujjain; ladies throw colored powder during the jubilant Holi festival; shopping at a roadside market in Jaffna, Sri Lanka; a mom and dad reading to their son; taking a stroll in sunny Tirupati; a young couple wait in queue for darshan of Sri Venkateshwara

There are many other ideals that help a family survive in Hinduism. An important one is that father and mother are the children’s first guru, first teacher of things of the spirit. This brings a deep honoring to the parent-child relationship. Such a tie transcends the physical, emotional, intellectual relationship that is the sum of some family bonds. It brings an air of sacredness into the interactions, a deeper reverencing which powerfully connects a daughter or son to his mother and father. One sees this expressed so beautifully in the traditional family when young ones gently and lovingly touch the feet of their parents. They are worshiping the Divine in their parents and thus being prepared to see God in everyone.

A Saivite father shares the teachings with his wife and children

In the strict Hindu family, there is a clear and well-understood hierarchy, based fundamentally on age. Younger members are taught to respect and follow the directions from their elders, and to cherish and protect those younger than themselves. Even differences of a few months are respected. Many problems that could arise in less-structured families—and do, as proven in the modern nuclear family—simply never come up. There is less vying for attention, less ego conflict, less confusion about everyone’s role and place. With the lines of seniority known to all, regulations, changes and cooperative exchanges flow freely among family members.

VOICES: In the family life, thousands of years ago, a Hindu was told, “Matridevo bhava, pitridevo bhava, acharya devo bhava.” This Sanskrit dictum means, “Be the one who respects his mother as God, his father as God and his guru or teacher as God.” Such an ultimate reverence for the elders creates a profound, serene feeling and certainly prepares the mind to receive the good and loving advice from them in the proper spirit. Bowing down before the elders in respectful salutation and touching their feet is an exclusively Hindu custom. When such a deep respect is accorded to family members, no wonder the family bonds are strong and they remain unified.

Daily worship in the home is a unique Hindu contribution to family sharing. Of course, faith is a shared experience in all religious households. But the Hindu takes it a step further, sanctifying the home itself with a beautiful shrine room—a kind of miniature temple right in the house. The father or oldest son is the family’s liturgist, leading others in daily ritual. Others care for the sacred implements, gather fresh flowers for the morning rites and decorate for holy days or festivals. In Hindu culture, family and spirituality are intimately intertwined.

VOICES: Every Hindu family in our village had a home shrine where the family members worship their Gods. Even the poorest set aside a place for this. Rituals are periodic celebrations which are religious and spiritual in character, and they address the inward feelings rather than outward. Such pujas and rituals give an individual a chance to pause, look inward and concentrate on something more meaningful, more profound, than mere materialism and the daily drudgery of life. Worships and rejoicings in the name of God, fasting and observances of special days enable people to look beyond the day-to-day life to a larger scheme of things. In the best homes I know, the father performs the rites daily, and the family joins and assists. I guess it’s like the old adage, “The family that prays together stays together.” Even in the busy rat race of life in cosmopolitan cities like Mumbai or Los Angeles, there are many Hindus who perform at least a mini puja daily. They claim that even the small ritual of a few minutes a day makes them concentrate, feel elevated spiritually, brings their minds on an even keel, enabling them to perform better in their line of work.

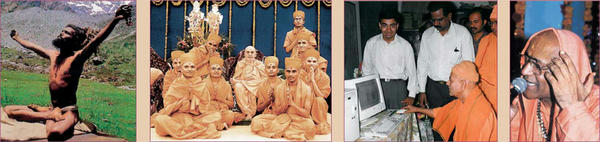

Scenes from Monastic Life

The scriptures exalt above every other good the greatness of virtuous renunciates. TIRUKURAL, VERSE 21

Sadhvis meditating in Hardwar; Swami Arunagirinatha, head of Madurai Aadheenam; Swami Chidananda Saraswati, head of Divine Life Society, giving darshan; a yogi in bliss; sadhus of Swaminarayanan Fellowship (BAPS) with their guru; Swami Gautamananda, head of Chennai’s RK Mission; Swami Achalanand Ji Maharaj of Jodhpur offers words of wisdom

Another family tradition is the kulaguru, or family preceptor. Though it is not required that every member of a Hindu family have the same guru, it often happens that way. This gives all members a shared spiritual point of reference, a voice whose wisdom will be sought in times of decision, difference or unclarity, a voice that will also be listened to, its advice followed. That means that there is a kind of outside counselor, a mediator to work out deadlocks, a referee to arbitrate and settle disputes. Thus, the family need never be stuck in some irresolvable impasse. The kulaguru’s counsel can be trusted to transcend the personalities involved, to be impersonal and just. And that simple practice can bring a family through many a quandary.

The preceptor is approached for blessings, and guidance

Hindu heritage gives a strong definition to the growth and maturing of family members, through the application of the ashramas. Every member in a family is expected to spend the first twenty-four years or so in the brahmacharya, or student, stage. It’s a time of learning, studying, serving and growing up. Then comes the stage of the grihastha, or householder, and with it marriage, children and social responsibilities. These stages are informally defined in nearly every culture, but in Hinduism the definitions are elaborately detailed beyond raising the family. Sometime around fifty, every member enters the vanaprastha ashrama, a stage of advisor and elder. By formalizing this stage, the Hindu family gives a place of prominence and usefulness to its senior citizens. They do not just retire, and they certainly are not sent off to a retirement home. Rather, their advice is sought, their years of experience drawn upon. Thus, Hinduism gives a place to those who have served the family in their youth but, with age, can no longer serve in that same way. They have a new place. Far from being a lesser function, it is a place of greater honor. This is one of the greatest gifts that the traditional Hindu family offers, thus averting one of the greatest tragedies: depriving elders of due recognition.

VOICES: My mother-in-law, right up till she died in her seventies, was the head of the household. She could do anything with my children, and I wouldn’t have the guts to tell her no. She would put kohl, mascara, adorning their eyes and oil in their hair, and their eyes would be black and their hair greasy, but I wouldn’t say anything to her. She would bribe the kids with candy, and they loved her for it. It’s a loving relationship, because you do something for someone and they do something for you. The blessings do come on you because she felt very wanted and happy. She taught me the sanctity of the family unit and respect for elders.

It is significant that Hindus, numbering over one billion today, constitute sixteen percent of the human race. One out of every six people on the planet is a Hindu. So, the ability of that large community to preserve its strengths, to pass on its values and cultural treasures, to protect its members and keep them well and fulfilled is important. Important does not suffice. Crucial, really. On the optimistic side, as much as eighty percent of Hindus live in rural India, in the 700,000 small villages which remain less affected by outside influences and thus retain the promise of carrying on the traditional ways, including language, religion and custom. As all the foregoing amply indicates, the Hindu concept of family is unique in many ways.

There is a more cosmic definition taught by every grandma and village elder, that in truth all of us on Earth are the creation of the One Great God; thus, in the broadest sense, we belong to a single family. Vasudhaiva kutumbakam—“The whole world is one family.” That’s not an innovative notion derived from New Age insights or Gaia ecology. It’s been part of Indian folk culture for thousands of years.

VOICES: I was always taught that we as Hindus must have a magnanimous attitude, that our Hindu religion visualizes the entire Earth as one family. But while looking at all human beings as one family, I also saw that elders deeply considered the smaller family unit, the dynamism of its members’ relationships with one another, and the pivotal role the institution of family plays in building the society.

THE IDEALS OF FAMILY LIFE

If both husband and wife are on the spiritual path, the householder family will progress beautifully and deeply. Their love for one another and their offspring maintains family harmony. However, the nature of their sadhana and unfoldment of the spirit is different from that of the sannyasin. The family unit itself is a magnetic-force structure, a material structure, for they are involved in the objects and relationships of the world. It is the family’s effort to be “in the world but not of it” that gives the impetus for insight and the awakening of the soul. The struggle to maintain the responsibilities of the home and children while simultaneously observing the contemplative way, in itself, provides strength and balance, and slowly matures innate wisdom through the years.

The successful Hindu householder family is stable, an asset to the larger community in which it lives, an example of joyous, contented relationships. Members of the family are more interested in serving than being served. They accept responsibility for one another. They are pliable, flexible, able to flow freely like water. They worship and meditate daily without fail and strictly observe their individual sadhanas. Their insight is respected and their advice sought. Yet, they do not bring the world into the home, but guard and protect the home vibration as the spiritual center of their life. Their commitments are always first to the family, then to the community. Their home remains sacrosanct, apart from the world, a place of reflection, growing and peace. They intuitively know the complex workings of the world, the forces and motivations of people, and often guide others to perceptive action. Yet, they do not display exclusive spiritual knowledge or put themselves above their fellow man.

Problems for them are merely challenges, opportunities for growth. Forgetting themselves in their service to the family and their fellow man, they become the pure channel for love and light. Intuition unfolds naturally. What is unspoken is more tangible than what is said. Their timing is good, and abundance comes. They live simply, guided by real need and not novel desire. They are creative, acquiring and using skills such as making their own clothing, growing food, building their own house and furniture. The inner knowing awakened by their meditations is brought directly into the busy details of everyday life. They use the forces of procreation wisely to produce the next generation and not as instinctive indulgence. They worship profoundly and seek and find spiritual revelation in the midst of life.

Maintaining a Balance of Forces

Within each family, the man is predominantly in the pingala force. The woman is predominantly in the ida force. When the energies are the other way around, disharmony is the result. When they live together in harmony and have awakened enough innate knowledge of the relation of their forces to balance them, then both are in the sushumna force and can soar into the Divinity within. Children born to such harmonious people come through from the deeper chakras and tend to be highly evolved and well balanced.

Should the woman become aggressively intellectual and the man become passively physical, then forces in the home are disturbed. The two bicker and argue. Consequently, the children are upset, because they only reflect the vibration of the parents and are guided by their example. Sometimes the parents separate, going their own ways until the conflicting forces quiet down. But when they come back together, if the wife still remains in the pingala channel, and the husband in the ida channel, they will generate the same inharmonious conditions. It is always a question of who is the head of the house, he or she? The head is always the one who holds the pranas within the pingala. Two pingala spouses in one house, husband and wife, spells conflict.

The balancing of the ida and pingala into sushumna is, in fact, the pre-ordained spiritual sadhana, a built-in sadhana, or birth sadhana, of all family persons. To be on the spiritual path, to stay on the spiritual path, to get back on the spiritual path, to keep the children on the spiritual path, to bring them back to the spiritual path, too—as a family, father, mother, sons and daughters living together as humans were ordained to do without the intrusions of uncontrolled instinctive areas of the mind and emotions—it is imperative, it is a virtual command of the soul of each member of the family, that these two forces, the ida and pingala, become and remain balanced, first through understanding and then through the actual accomplishment of this sadhana.

One thing to remember: the family man is the guru of his household. If he wants to find out how to be a good guru, he just has to observe his own satguru, that is all he has to do. He will learn through observation. Often this is best accomplished by living in the guru’s ashrama periodically to perform sadhana and service. Being head of his home does not mean he is a dominant authority figure, arrogantly commanding unconditional obedience, such as Bollywood and Hollywood portray. No. He must assume full responsibility for his family and guide subtly and wisely, with love always flowing. This means that he must accept the responsibility for the conditions in the home and for the spiritual training and unfoldment of his wife and children. This is his purusha dharma. To not recognize and not follow it is to create much kukarma, bad actions, bringing back hurtful results to him in this or another life.

When the wife has problems in fulfilling her womanly duties, stri dharma, it is often because the husband has not upheld his duty, nor allowed her to fulfill hers. When he does not allow her to or fails to insist that she perform her stri dharma and give her the space and time to do so, she creates kukarmas which are equally shared by him. This is because the purusha karmic duty and obligation of running a proper home naturally falls upon him, as well as upon her. So, there are great penalties to be paid by the man, husband and father for failure to uphold his purusha dharma.

Of course, when the children “go wrong” and are corrected by the society at large, both husband and wife suffer and equally share in the kukarmas created by their offspring. In summary, the husband took the wife into his home and is therefore responsible for her well-being. Together they bring the children into their home and are responsible for them, spiritually, socially, culturally, economically, as well as for their education.

What does it mean to be the spiritual head of the house? He is responsible for stabilizing the pranic forces, both positive, negative and mixed. When the magnetic, materialistic forces become too strong in the home, or out of proper balance with the others, he has to work within himself in early morning sadhana and deep meditation to bring through the spiritual forces of happiness, contentment, love and trust. By going deep within himself, into his soul nature, he uplifts the spiritual awareness of the entire family into one of the higher chakras.

The family woman has to be a good mother. To achieve this, she has to learn to flow her awareness with the awareness of the children. She has been through the same series of experiences the children are going through. She intuits what to do next. As a mother, she fails only if she neglects the children, takes her awareness completely away, leaving the children to flounder. But if she stays close, attends to each child’s needs, is there when he or she cries or comes home from school, everything is fine. The child is raised perfectly. This occurs if the wife stays in the home, stabilizing the domestic force field, where she is needed most, allowing the husband to be the breadwinner and stabilizer of the external force field, which is his natural domain.

The Hindu woman is trained to perform her stri dharma from the time she is a little girl. She finds ways to express her natural creativity within the home itself. She may write poetry or become an artist. Perhaps she has a special talent for sewing or embroidery or gardening or music. She can learn to loom cloth and make the family’s clothing. If needed, she can use her skills to supplement the family income without leaving the home. There are so many ways for a Hindu wife and mother to fully use her creative energies, including being creative enough to never let her life become boring. It is her special blessing that she is free to pursue her religion fully, to study the scriptures, to sing bhajana and keep her own spiritual life strong inside.

If each understands—or at least the family man understands, for it is his home—how the forces have to be worked within it, and realizes that he, as a man, flows through a different area of the mind than does his wife in fulfilling their respective, but very different, birth karmas, then everything remains harmonious. He thinks; she feels. He reasons and intellectualizes, while she reasons and emotionalizes. He is in his realm. She is in her realm. He is not trying to make her adjust to the same area of the mind that he is flowing through. And, of course, if she is in her realm, she will not expect him to flow through her area of the mind, because women just do not do this.

Usually it is the man who does not want to, or understand how to, become the spiritual head of his house. Often he wants the woman to flow through his area of the mind, to be something of a brother and pal or partner to him. Therefore, he experiences everything that goes along with brothers and pals and partners: arguments, fights, scraps and good times. In an equal relationship of this kind, the forces of the home are not building or becoming strong, for such a home is not a sanctified place in which they can bring inner-plane beings into reincarnation from the higher celestial realms. If they do have children under these conditions, they simply take “potluck” off the lower astral plane, or Pretaloka.

A man goes through his intellectual cycles in facing the problems of the external world. A woman has to be strong enough, understanding enough, to allow him to go through those cycles. A woman goes through emotional cycles and feeling cycles as she lives within the home, raises the family and takes care of her husband. He has to be confident enough to understand and allow her to go through those cycles.

Rather than arguing or talking about their cycles, the man who is spiritual head of his house meditates to stabilize the forces within himself. He withdraws the physical energies from the pingala and the ida currents into sushumna in his spine and head. He breathes regularly, sitting motionless until the forces adjust to his inner command. When he comes out of his meditation, if it really was a meditation, she sees him as a different being, and a new atmosphere and relationship are created in the home immediately. The children grow up as young disciples of the mother and the father. As they mature, they learn of inner things. It is the duty of the mother and the father to give to the child at a very early age his first religious training and his education in attention, concentration, observation and meditation.

The parents must be fully knowledgeable of what their child is experiencing. During the first seven years, the child will go through the chakra of memory. He will be learning, absorbing, observing. The second seven years will be dedicated to the development of reason, as the second chakra unfolds. If theirs is a boy child, he is going through the pingala. If a girl child, she is going through the ida current and will go through emotional cycles.

Religion begins in the home under the mother’s influence and instruction. The mother goes to the temple to get strong. That is the reason Hindus live near a temple. They go to the temple to draw strength from the shakti of the Deity, and they return to the home where they maintain a similar vibration in which to raise the next generation to be staunch and wonderfully productive citizens of the world, to bring peace on Earth, to keep peace on Earth. There is an ancient South Indian proverb which says one should not live in a city which has no temple.

By both spouses’ respecting the differences between them and understanding where each one is flowing in consciousness, there is a give and take in the family, a beautiful flow of the forces. The acharyas and swamis work with the family man and woman to bring them into inner states of being so that they can bring through to the Earth a generation of great inner souls. It is a well-ordered cycle. Each one plays a part in the cycle, and if it is done through wisdom and understanding, a family home is created that has the same vibration as the temple or a contemplative monastery.

A contemplative home where the family can meditate has to have that uplifting, temple-like vibration. In just approaching it, the sushumna current of the man should withdraw awareness from the pingala current deep within. That is what the man can do when he is the spiritual head of the home.

Scenes from Family Life

He who rightly pursues the householder’s life here on Earth will be rightfully placed among the Gods there in Heaven. TIRUKURAL, VERSE 10

A tiny infant in loving arms; women at the market in Nepal; boys meditate at the Tirunavakarasu Ashram/Gurukulam in Sri Lanka; a family perform havan, the Vedic fire ceremony; a young family, heads shaven as an act of penance, enjoy rice and curry prasadam at Tirupati Temple; a devotee sings devotional hymns; renowned dancer Paolomi Ashwinkumar

India’s Venerable Renunciate Tradition

enunciation and asceticism have been integral components of Hindu culture and religion from the earliest days, the most highly honored facet of the Hindu Dharma. The ideal of the life-long celibate monastic, living within the social order and yet freed from worldly obligation that he might find and shed his spiritual light, started before the Mohenjodaro and Harappa civilizations of five thousand years ago and traces its development in the references in the Rig Veda, to the munis and the yatis, men who wore long hair and yellow robes, such men as Sanatkumara, Dattatreya and others, all naishtika brahmacharis [lifelong celibates]. Later in the Vedas the sannyasa ashrama, or last stage of the four-fold division of life, became formalized, and many references are made to those who after age seventy-two relinquished all in search of the Absolute.

enunciation and asceticism have been integral components of Hindu culture and religion from the earliest days, the most highly honored facet of the Hindu Dharma. The ideal of the life-long celibate monastic, living within the social order and yet freed from worldly obligation that he might find and shed his spiritual light, started before the Mohenjodaro and Harappa civilizations of five thousand years ago and traces its development in the references in the Rig Veda, to the munis and the yatis, men who wore long hair and yellow robes, such men as Sanatkumara, Dattatreya and others, all naishtika brahmacharis [lifelong celibates]. Later in the Vedas the sannyasa ashrama, or last stage of the four-fold division of life, became formalized, and many references are made to those who after age seventy-two relinquished all in search of the Absolute.

The ancient shastras recognize four justifiable motivations for entering into sannyasa: vidvat, vividisha, markata and atura. Vidvat (“knowing; wise”) sannyasa is the spontaneous withdrawal from the world in search for Self Realization which results from karma and tendencies developed in a previous life. Vividisha (“discriminating”) sannyasa is renunciation to satisfy a yearning for the Self developed through scriptural study and practice. Markata sannyasa is taking refuge in sannyasa as a result of great sorrow, disappointment or misfortune in worldly pursuits. Atura (“suffering or sick”) sannyasa is entering into sannyasa upon one’s deathbed, realizing that there is no longer hope in life.

Renunciation of the world found a high expression in the monastic principles of Jainism and Buddhism, both religions founded by illustrious sons of India. Siddhartha Gautama, the Buddha, was born and died a Hindu in the seventh century bce. He himself cherished, lived and promulgated the ascetic ideal within the compass of Hinduism, and his followers made a separate religion of his teachings after his death. It is only in Hinduism and the Hindu-inspired religions of Jainism and Buddhism that asceticism is a vibrant and valued mode of life, a part of the natural dharma. Though the homeless sadhu and the wandering mendicant existed before, it was Gautama Buddha who around six hundred years bce, organized what had been an individual sadhana into a monastic order, which he termed the sanga. In the early 9th century, Adi Shankaracharya, the great exemplar of the ideals of sannyasa who revitalized and restored the ancient ways during his short life of thirty-two years, organized the Hindu monastics of his day. In his travels throughout India, he assessed the existing traditions and finally validated ten orders of ascetics, at the same time establishing four religious centers or pithas in the North, East, South and West of India, known respectively as Jyotih, Govardhana, Sringeri and Sharada. Each dashanami order is loosely associated with one of the four centers. A fifth prominent pitha, associated with Sringeri Matha, is in Kanchipuram, also in the South. Thus, the ancient order of sannyasa extends back to time immemorial, structurally influenced by Gautama Buddha about twenty-five centuries ago and revitalized in its present form by Adi Shankaracharya around twelve hundred years ago.

Today the total number of monks in India and the world is not known for sure. Estimates range from one million to as high as five million, as there is naturally no official census or way of counting those who live this reclusive life. One of the largest of Hindu orders is the sadhu order known as Juna Akhara, which has 150,000 sadhus. Sadhu means “virtuous one,” and is a holy man dedicated to the search for God. There are thirteen such sadhu akharas. The Juna Akhara and Niranjani Akhara are the most prominent. Others include the Agan, Alakhiya, Abhana, Anand, Mahanirvani and Atal. Most of these orders are considered Saivite; three are Vaishnavite (formed beginning in 1299 by Saint Ramananda Ji) and a few are Sikh orders patterned after the Hindu monastic system. Akhara is a Hindi term meaning “wrestling arena.” It can mean either a place of verbal debate or one of physical combat. Sadhus of the various akharas may also hold allegiance to one of the ten dashanami orders: Sarasvati, Puri, Bana, Tirtha, Giri, Parvati, Bharati, Aranya, Ashrama and Sagara. Thus, the akharas overlap with the dashanami system. The akharas’ dates of founding range from the sixth to the fourteenth century, though large monastic orders have existed throughout India’s long history. Several akharas run hundreds of ashramas, schools and service institutions.

Meetings of the Ways

Domestic life is rightly called virtue. The monastic path, rightly lived beyond blame, is likewise good. TIRUKURAL, VERSE 9

Sadhus march with dandas at the Kumbha Mela; Swamis in South Africa conclave with lay leaders; Satguru Sivaya Subramuniyaswami chats with a young seeker; Swami Avdheshananda Ji Giri speaks on Hinduism; the mayor of Bratislava, Slovakia, cuts the ribbon with Swami Maheshwarananda to his new yoga center; sadhus in procession; saints give blessings

The majority of sadhus live in various akhara camps scattered all over India. Holy cities, including Rishikesh, Haridwar, Nashik, Prayag, Varanasi, Vrindavan and Ujjain have permanent akhara camps. Many sadhus move constantly from one camp to another. Those swamis and sadhus who are not a part of an akhara live in independent mathas and ashramas situated all over the country, or wander as mendicants. There is also the important aadheenam tradition, not associated with the dashanami orders, a series of ancient monastery-temple complexes in Tamil Nadu.

A large number of sadhvis, women monks, perhaps as many as 100,000, are a part of the akhara system, though they live separately from the men, and even during the massive Kumbha Mela festivals they have separate camps.

There are also sannyasin orders, such as the Nathas, that exist outside the dashanami and akhara systems.

Additionally, several large cenobitic orders have branches outside India, such as the Ramakrishna Mission, with 1,000 sannyasins; Swaminarayan Gadi, with 1,500 sadhus; BAPS Swaminarayan Sanstha, with 700 sadhus and brahmacharis; and the Chinmaya Mission, with 100 swamis and swaminis.

The famed Kumbha Mela is fundamentally a gathering of the great monastic orders of India. At the high point of the Mela festivals, hundreds of thousands of renunciate monks travel in grand procession to a nearby river’s edge for the shahi snan, “royal bath,” while pilgrims line the streets to receive their blessings. The Kumbha Mela is a time to elect new akhara leadership, discuss and solve problems, consult with the other akharas, meet with devotees and initiate new monastics.

There are countless sadhus on the roads, byways, mountains, riverbanks, and in the ashramas and caves of India. They have, by their very existence, a profound, stabilizing effect on the consciousness of India and the world. It is well known that through their austerity and renunciation, the sadhus and sannyasins help consume and balance out the karma of the community at large. They are honored for the unseen benefits in the wise culture of India, and many people help support them with donations.

Today, Hindu monastics and their institutions are, for the most part, growing, thriving, while monastic traditions in other faiths are facing an erosion of numbers. This bodes well for the future of Hinduism, for the monastics are the spiritual guides and inspirers.

While Hindu monasticism is not a centralized system, it does have a competent and substantial organized leadership of gurus revered by their followers. There are also various oversight bodies. Among the akharas, for example, there is the Akhara Parishad and the Chatur Sampradaya. The Delhi-based assembly, the Acharya Sangam, is a voice for some 15,000 sadhus.

Contrary to modern misconceptions, Hindu monks and families are closely associated, each helping the other in their chosen expression of dharma. Many sadhus and swamis personally guide the lives of hundreds of families. Many run institutions that provide social service. Even orders that keep their distance from society work to bring the philosophical teachings to the masses. Others live a strictly reclusive life, going deep to the source of existence in their meditations and uplifting mankind through their mere existence in elevated states of consciousness.

From the point of view of the Second World, or astral plane, the home is the family temple, and the wife and mother is in charge of that spiritual environment. The husband can come into that sanctum sanctorum but should not bring the world into it. He will naturally find a refuge in the home if she is doing her duty. He will be able to regain his peace of mind there, renew himself for the next day in the stressful situations that the outside world is full of. In this technological age a man needs this refuge. He needs that inner balance in his life. When he comes home, she greets him at the entrance and performs a rite of purification and welcome, offering arati to cleanse his aura. This and other customs protect the sanctity of the home. When he enters that sanctuary and she is in her soul body and the child is in its soul body, then he becomes consciously conscious in his soul body, called anandamaya kosha in Sanskrit. He leaves the conscious mind, which is a limited, external state of mind and not a balanced state of mind. He enters the intuitive mind. He gets immediate and intuitive answers to his worldly problems.

A woman depends on a man for physical and emotional security. She depends on herself for her inner security. He is the guide and the example. A man creates this security by setting a positive spiritual example. When she sees him in meditation, and sees light around his head and light within his spine, she feels secure. She knows that his intuition is going to direct his intellect. She knows he will be decisive, fair, clear-minded in the external world. She knows that when he is at home, he turns to inner and more spiritual things. He controls his emotional nature and he does not scold her if she has a hard time controlling her emotional nature, because he realizes that she lives more in the ida force and goes through emotional cycles. In the same way, she does not scold him if he is having a terrible time intellectually solving several business problems, because she knows he is in the intellectual force, and that is what happens in that realm of the mind. She devotes her thought and energies to making the home comfortable and pleasant for him and for the children. He devotes his thought and energies to providing sustenance and security for that home.

The man seeks understanding through observation. The woman seeks harmony through devotion. He must observe what is going on within the home, not talk too much about it, other than to make small suggestions, with much praise and virtually no criticism. He must remember that his wife is making a home for him, and he should appreciate the vibration she creates. If he is doing well in his inner life, is steady and strong, and she is devoted, she will flow along in inner life happily also. She must strive to be one with him, to back him up in his desires and his ambitions and what he wants to accomplish in the outside world. This makes him feel strong and stand straight with head up. She can create a successful man of her husband very easily by using her wonderful intuitive powers. Together they make a contemplative life by building the home into a temple-like vibration, so blissful, so uplifting.

In the home, the mother is likened to the Shakti Deity. She is the power, the very soul of the home. None other. So she has to be there. She has to be treated sensitively and kindly, and with respect. She has to be given all the things she needs and everything she wants so she will release her shakti power to support her husband, so that he is successful in all his manly endeavors. When she is hurt, depressed, frustrated or disappointed, she automatically withdraws that power, compromising his success in the outside world along with it. People will draw away from him. His job, business or creative abilities will suffer. This is her great siddhi, her inborn power, which Hindu women know so well.

How can he not be successful in his purusha dharma in the outside world when he has the backing of a good wife? She is naturally perceptive, naturally intuitive. She balances out his intellect, softens the impact of the forces which dash against his nervous system from morning to night. Encouragement and love naturally radiate out from her as she fulfills her stri dharma. Without these balancing elements in his life, a man becomes too externalized, too instinctive.

It is the man’s duty, his purusha dharma, to provide for her and for the children. The husband should provide her with all the fine things, with a good house which she then makes into a home, with adornments, gold and jewels and clothes, gold hanging down until her ears hurt, more bracelets, more things to keep her in the home so she is feeling secure and happy. In return she provides a refuge, a serene corner of the world where he can escape from the pressures of daily life, where he can regain his inner perspective, perform his religious sadhana and meditations, then enjoy his family. Thus, she brings happiness and peace of mind to her family, to the community and to the world.