Defending the view that “Difference is real”

There has always prevailed in India a tolerant view regarding differences of philosophical opinion. Hindu dharma not only tolerates, but encourages a grand diversity of opinions on ultimate issues, on matters of spiritual faith and practice. And it believes neither in aggressive conversion nor imposing its spiritual world view on others. Nurtured by this environment of free expression, countless great lineages of Hindu culture have emerged throughout history as India’s great thinkers have given their interpretations of Vedic wisdom according to their experience and realization.

This Educational Insight takes us back to the thirteenth century in South India, where fervent public debates on the nature of truth were (as they are to this day) held between luminaries of various faiths and traditions. While religionists of Europe and the Middle East were immersed in bloody battles which they called the Holy War, great, spiritual warriors in India were locked in battles of wits and will. The goal was not land or booty, but correct knowledge of the nature of reality. If one’s point of view could be proven with impeccable logic and scriptural evidence, it had to be true. At their best, these were powerful, mystical encounters in which those present rose together to touch into higher planes of knowing and draw from the infinite well of wisdom. Such discussions were so sincere that the one who lost, if fully convinced of the other’s point of view, might embrace his school of thought and become a faithful follower.

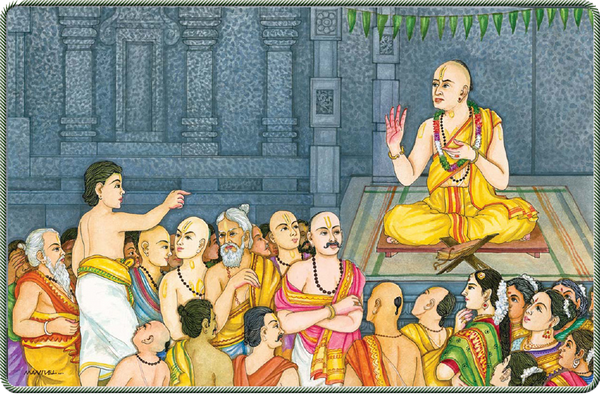

As a boy, Madhva had already mastered and memorized the scriptures of Vedanta. His mother took him to a public lecture one day. When the speaker made an error interpreting a text, he boldly stood up to point out the mistake and offered the correct view, which the pundit gratefully accepted.

A. MANIVEL

In those days, the prevailing Vedanta philosophy was the severely monistic view of Sri Adi Shankara (788–820ce), a brilliant young monk and intellectual giant who had traveled the length and breadth of India as a reviver of Hindu thought and practice. From his efforts and those of his followers emerged the highly influential and philosophically compelling system known as Advaita Vedanta, the core belief system of the Smarta Sampradaya, one of the most prominent denominations of Hinduism to this day. He built his seemingly unassailable fortress of logic not only by speaking, but by writing. His prolific commentaries on the three pillars of Vedic evidence—the ten principle Upanishads, the Bhagavad Gita and the Brahma Sutra—became the benchmark of Vedantic thought. In a nutshell: everything is illusion; only the Absolute, Brahman, is real. The goal, as defined in scripture, is to break the spell of illusion with the power of discrimination and realize the oneness of soul and God.

While Shankara’s view was prominent, it was not the only way Hindus viewed life or interpreted the holy books. In the centuries that followed, many luminaries challenged his system. To do so, each wrote commentaries on the same texts he had analyzed, and avidly debated with monastic and lay scholars of the Shankara school. Each in his day stood up and propounded his own view of what the scriptures really mean, while refuting, point-by-point, the contentions that Shankara had given forth. Because Shankara’s philosophy was so articulately stated, widely known and deeply established, the great thinkers who followed him defined their school of thought by debating the assertions of Shankara.

Between the eleventh and sixteenth centuries, five such masters (see here) loom the largest in the halls of Indian history. All from the Vaishnava tradition, two lived in South India and three in the North. Among them was Sri Madhva, born in Karnataka. From his early teens, he was disturbed by the pervasive advaitic notion that we are all caught up in some fantastic dream in which Bhagavan, his beloved Lord, is ultimately nothing more than a phantom. “It is not true,” he swore one day after completing his priestly training, “and I will prove it wrong.”

Madhva’s lifelong debate with Shankara centers around the definitions of Self, the reality or unreality of the world and the nature of the ultimate transcendental goal. His investigation begins with the Brahma Sutra, a pithy, 550-verse text that stitches together the varied scriptures of Vedanta, including the Upanishads and the Bhagavad Gita, into a consistent whole. Its first verse reads, “Athato Brahma jijnasu,” meaning, “Now, therefore, let us inquire into the nature of the transcendent reality.” Does it have qualities, forms, distinctions and individuality similar in any way to those we experience in the realm of matter? Or is it pure advaita, a boundless, unified, homogenous existence, without individuality, distinctions and forms, as Shankara claims: “Jagat mithya brahma satya,” “The world is false or illusory, and Brahman, the non-distinctive reality, is the only truth.”

Vedanta: One of Six Hindu Darshanas

There are six classical darshanas, or ways of seeing and investigating reality in the Hindu tradition: Sankhya, which is material science; Nyaya, logic and epistemology; Vaisheshika, physics and atomic theory; Yoga, spiritual practice and meditation; Purva Mimamsa, hermeneutics and ritual worship; and Vedanta (Uttara Mimamsa), metaphysics. Vedanta is dedicated to defining the transcendental goal of life and outlining the means to its attainment. The word Vedanta tells it all—the “end” (anta) or “conclusion” of the Vedas.

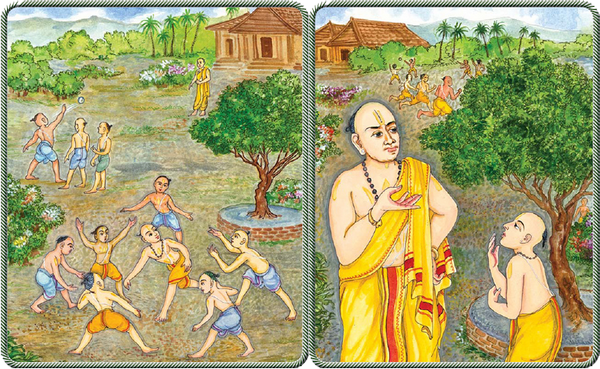

The youthful Madhva spent most of his days in athletic pursuits with schoolmates. When his teacher, Totanillaya, advised he should spend more time practicing his chanting, Madhva countered that he had memorized and perfected all the verses that had been taught. A disbelieving Totanillaya challenged the claim, and Madva then perfectly recited the shlokas from memory. The teacher never again questioned the boy’s study habits.

A. MANIVEL

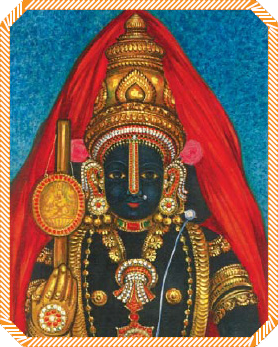

In contrast, Madhva seeks to prove from scriptural statements that the Ultimate is a personal, lovable Supreme Being who is the source of all beauty, truth, unity and diversity. Further, the atma, soul or self, is eternally an individual, both in the material realm and in the transcendental. The names and forms we see temporarily manifested in the realm of matter are reflections of the eternal names and forms; and the transcendental realm, the material realm, souls and the Supreme Being are all eternally different and distinctive. His emphatic declaration is “Difference is real; difference is real; difference is real.” That mantra is captured in the famous portrait in which he holds up his right hand with middle and index finger extended, a simple mudra indicating distinction (see here).

Shankara defines moksha, the soul’s liberation from the cycle of rebirth, as the shedding of all distinctions, forms and personhood to merge in the timeless, seamless, formless reality of Brahman. Madhva’s doctrine, which to this day forms the backbone of several Vaishnava bhakti schools, asserts that the individual atma and the Supreme Paramatma, as well as their friends, associates and paraphernalia, exist for eternity in the transcendental realm. There they engage in various loving activities beyond the reach of the temporary material realm, in which birth, death, old age and disease interrupt our potential for eternal, loving service. That pure activity, called bhakti, or devotion, is the goal of life and ultimate message of the scriptures.

This very personal and permanent relationship with Divinity contrasts starkly with the view of Shankara—which ultimately considers the relationship between the worshiper and Bhagavan, God, as but another aspect of the grand illusion that must be transcended—and argues that liberation, being a formless state, can alone be attained by the path of jnana, the cultivation of knowledge of the impersonal Absolute, Brahman.

Shankara’s Advaita defines the extreme left pole of Vedanta. In the middle range are the Vishishtadvaita views of Ramanuja, the Achintya-Bheda-Abheda-Tattva of Chaitanya and others. Madhva’s Dvaita, called Distinctive Realism, is at the extreme right pole.

What Evidence Is Trustworthy?

Madhva defines the three valid sources of the truth: perception, inference and testimony: “Perception is the flawless contact of sense organs with their appropriate objects. Flawless reasoning is inference. Flawless words conveying valid sense is testimony.”

Perception is pratyaksha, inference is anumana and testimony is agama. Agama is another name for the Vedantic library of evidence, all of which is considered divinely given information or testimony. All three sources of information—sense perception, inferential reasoning and scripture—are always accurate in varying degrees, and all three can be perfected and relied upon. This stands in contrast to Shankara’s assertion that inference and perception, like the world, are illusory, and testimony alone can lead us to the undifferentiated, impersonal conclusion regarding the nature of reality.

Sect/Sampradaya:

Shri Vaishnava

Founder:

Ramanuja (1017 to 1137)

Philosophy:

Vishishta-advaita

Spheres of Influence:

Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka

Sect/Sampradaya:

Sanakadi Vaishnava

Founder:

Nimbarka (13th century)

Philosophy:

Dvaita-advaita

Spheres of Influence:

Karnataka, Maharashtra, Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu

Sect/Sampradaya:

Brahma Vaishnava

Founder:

Madhva (1238–1317)

Philosophy:

Dvaita

Spheres of Influence:

Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Bengal

Sect/Sampradaya:

Rudra Vaishnava

Founder:

Vallabhacharya (1479–1531)

Philosophy:

Shuddha-advaita

Spheres of Influence:

Rajasthan, Gujarat, Uttar Pradesh

Sect/Sampradaya:

Gaudiya Vaishnava

Founder:

Chaitanya (1486–1533)

Philosophy:

Achintya Bheda-Abheda Tattva

Spheres of Influence:

Bengal and Orissa

This valuable summary is drawn from The Sri-Krsna Temple at Udupi, by B. N. Hebbar, who notes that “all five schools are theistic and realistic reactions to the absolutistic idealism of Shankara’s Advaita Vedanta…. The first two are South Indian and follow the aishvarya bhakti-marga (Master-servant relationship between the Lord and His devotee), while the latter three are North Indian and adhere to the madhurya bhakti-marga (Lover-beloved relationship between the Lord and His devotee). Also, while the Lakshmi-Narayana concept predominates South Indian Vaishnavism, the Radha-Krishna element pervades the three North Indian Vaishnava sects.”

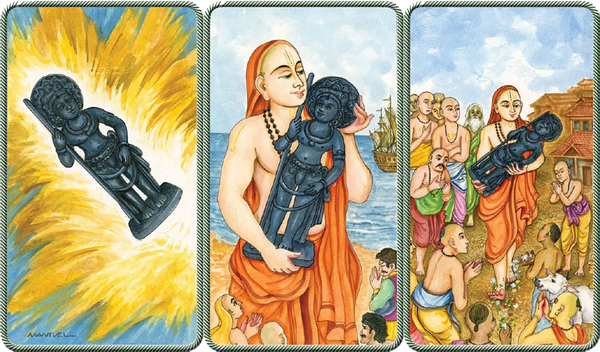

Around 1278, Madhva received a large mound of yellow clay from a ship captain in appreciation for his magically preventing the ship from capsizing during a gale. Inside the mound Madhva discovered an ancient stone murti of Gopi Krishna, which he carried to his monastery. Along the way, devotees are placing flowers at his feet in adoration. Below: The decorated Gopi Krishna murti that Madhva retrieved at Malpe Beach is still worshiped today.

A. MANIVEL

Madhva also berated Shankara for misusing inference, as he does in the following argument: The world is imperfect, illusory and has form; therefore, the transcendental, which is not illusory, must not have form. Here is Madhva’s retort: “If inference is said to negate perception, when perception is not negated by another perception of equal strength, what then is the talk of the wretch, inference, who lives at the feet of perception, being the negator of that!” In other words, we cannot infer anything without the evidence of our senses. Thus, inference can be used to correct our perceptions but never to totally negate them. Yet, Shankara uses inference to not only prove the formlessness of the transcendental world but also deny the entire material realm and negate its reality, forming the crux of his philosophical stance by a method he himself decries as illusory.

Madhva inquires: “What or who, in fact, is the ultimate perceiver or validator of any information?” He answers that it is the soul’s intrinsic intuitive faculty, known in scripture as sakshin, the witness. He explains: “The cognitive senses are of two kinds: the intuitive faculty, sakshin, or the cognitive agent, which is identical with the self; and the ordinary cognitive senses and the mind, which are made of matter.” Each atma has dormant spiritual senses which, when activated, are the instruments by which conclusive truth is perceived: “The perception by the sakshin is that which, in our experience, is not open to contradiction and which is decisive in character. Knowledge that is acquired through sensory channels and the mind, and is thus subject to discrepancies, is to be regarded as a modification of the mind-stuff. The latter is liable to correction and contradiction, while the perceptions of sakshin are not. What is thus established by the flawless verdict of sakshin must be regarded as true and valid for all time.”

The saint argues that if there is no higher sense by which to verify the refutation of sakshin, then there is also no one to verify the conclusion that it stands contradicted. In other words, we must have an inherent faculty that can validate the truth; otherwise it can neither be validated nor rejected. The acceptance of an eternal sensibility, the individual soul—which is in its essential nature pure, conscious and infallible—is the ground on which Madhva discusses the nature of reality. He posits that the atma, or soul, is the final arbiter of the truth of anything.

A. MANIVEL

Differences Are Real

While Madhva’s Dvaita philosophy has been construed as dualism, it, in fact, articulates a view of multiple realities that all have particular natures and are all real. Madhva’s view is not dualistic, because he did not limit existence to two realities, pitted against one another, but rather described how the various categories of reality are eternally real. To him, the differences among things are not mere illusions to be denied outright, but rather are a gradient of different types of existence among which the eternal souls, who are distinctive individuals, are allowed to choose.

Madhva divided differences into five types, which he called Prapancha and described as the five-fold differences that lead to excellence and liberation and constitute right knowledge. The five distinctions are between the Supreme and souls, the Supreme and matter, souls and souls, souls and matter, and matter and matter. For Madhva, difference is not at all a lower order of reality but is, in fact, the essence and true message of all the scriptures of Vedanta.

Shankara presents a radically different view in an earthy analogy: A man went to an outhouse at sunset and while there put his hand on a coiled-up rope, which he mistook for a snake. At first he was afraid the snake would bite him. When he realized that the snake was mithya, or false, the illusion was dispelled and he was released from his fear. Similarly, when the soul realizes the unreality of the world, it merges into the nondual and nondistinct Brahman.

To counter, Madhva presents his “transcendental realist” argument: “If this universe is to be regarded as imagined by our delusion (like the illusory snake in the rope), it would require the acceptance of a real universe that is the prototype of the imagined one. No theory of illusion can be demonstrated without at least two reals: a substratum of the illusion and a prototype of the superimposed object.” Madhva’s contention is that this material world is a reflection of the transcendental realm. Both realms have form and are real, even though one is temporary and the other is eternal. All differences are real, though some are temporary.

When the scriptures speak of the world as illusory, dream-like or unreal, Dvaitins understand this to mean that it is a temporary manifestation of reality. When compared to realities that are eternal, it is less real in the sense of duration but no less real during the time of its manifestation. Just as in the case of the mirage of a lake seen in a desert, the perceptions of lake, desert, water, etc., are all real, but they are not where they appear to be (in the desert). Madhva argues that the reality of the world cannot be undermined, because it is our experience in the world from which all other stages of being are reached. He scolds Shankara: “If the universe is illusion, its creator must be no better than a juggler in rags who goes about giving performances in magic to eke out his livelihood.”

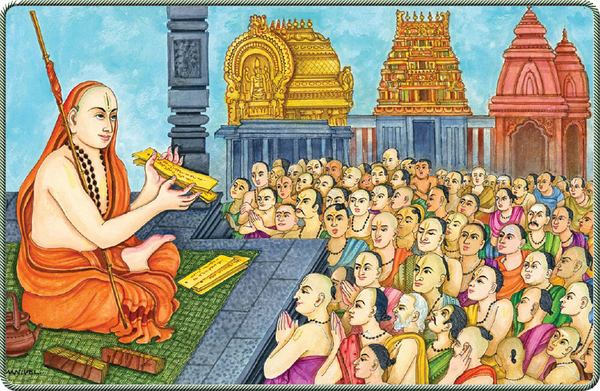

On his long, philosophical campaigns throughout India, Madhva mesmerized audiences from North to South (indicated by the varied temple towers). Crowds were captivated by his charismatic presence and mastery of polemics and scripture, and many became devout followers.

A. MANIVEL

The Nature of the Soul

The point of dispute is not whether the material world is a desirable place of residence for the soul, as Madhva and Shankara agree that liberating the soul from matter is the goal of Vedanta. Where they diverge sharply is on the nature of the soul. To Shankara, there is actually only one atma, or soul, in the whole of existence, and that great soul is called Brahman. Due to inexplicable ignorance, or maya, that one soul imagines itself (and thus appears) to be many. To Madhva, souls are multiple and eternally individual, real and distinct from Brahman, while at the same time one with it in essence. To support his position, Shankara quotes from Vedanta’s “identity texts,” while Madhva cites “difference texts,” such as the following verse from the Bhagavad Gita 14:27, in which Krishna says: “I am the basis of that impersonal Brahman, which is immortal, imperishable and eternal, and is the constitutional position of ultimate happiness.” Madhva interprets this to mean that the soul is an eternal spark or part of the energy of the Being who is the source of the Supreme Brahman.

In assailing Shankara’s position, Madhva queries: If Brahman is the Supreme, how could there be a greater power that could put it under illusion? If Brahman has no parts, how can there be a Brahman that is both liberated and not liberated? If there is no liberated Brahman, how could liberation be possible? If the world is merely a dream, since many individuals are seen in the world, whose dream is it? How could someone teach of the non-distinctive Brahman if he did not recognize the need to teach it, which is in itself a distinction?

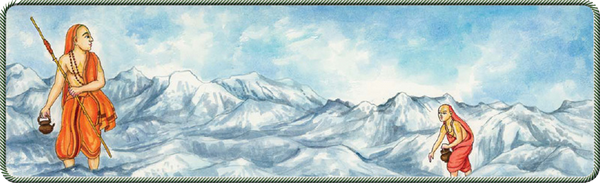

Madhva, on his way to fi nd Rishi Vedavyasa in the high Himalayas, realizes that Satyatirtha, his disciple, has been following him

A. MANIVEL

Karma and the Individual Soul

From Madhva’s point of view, each soul has a spiritual body, which is its true identity. When that eternal individual enters the realm of matter, it becomes covered with many layers of dark and unconscious matter. As a result, the soul’s true nature goes dormant and is forgotten. In that bewildered state, the atma takes on material bodies, beginning with the lowest species and eventually ascending the ladder of reincarnation to human birth. Throughout these incarnations, the soul identifies fully with its material body and mind.

When the soul reaches the human condition, its further progress is determined by its own actions, according to its free will. Material nature, or the natural mechanism of karma, responds like a mirror to this stream of choices. Through this unfolding process, souls may elevate themselves to the highest stratum of the material world or propel themselves to the lowest. Madhva points out that though he and Shankara agree that in order to achieve liberation, souls must carefully follow nature’s laws by adhering to good moral conduct, the laws of nature are real distinctions that lead the real soul to another reality and are not false presentations, as claimed by Shankara.

In theory, once a soul is within matter, it is possible for it to behave so badly that, by the laws of karma, it could become caught up in virtually endless bondage. Some critics have likened this aspect of Madhva’s doctrine to the Christian belief in eternal damnation. But the two views are actually quite different. Christianity believes in a single lifetime, before which the soul does not exist, and it does not believe in karma as a law of nature. Further, Christianity’s damnation to hell is moral punishment meted out by a vengeful God. Madhva’s view is of an eternally divine soul that is lost in matter but could release itself from bondage. Its sufferings within matter are temporary, not eternal, and are not the result of a punishment by a condemnatory God, but a self-imposed consequence of wrong action in relation to the rules that govern matter.

Realizing that he young monk has grown too weak to either proceed or go back, Madhva sends a supernatural burst of air which carries Satyatirtha to the safety of their base camp at Badri

A. MANIVEL

The Means to Liberation

Madhva proclaims that Vedanta’s ultimate conclusion is that the highest substance is the Supreme Brahman—Bhagavan, Vishnu, Hari—in all His eternal forms and avatars, as well as His supernal form, eternally full of all beauty and distinctions in the transcendental abode and destination. The definition of Bhagavan, the Supreme Person, is bhaga, “wealth” (the six-fold opulence of riches, strength, knowledge, fame, beauty and renunciation), and van which means “who possesses.” That being is also designated as Krishna, the Being who is by eternal nature the most attractive. Because the soul remains a distinct individual, now and in the transcendental state in the future, karma yoga and especially bhakti yoga are the surest means by which the soul achieves liberation and continues to act in the liberated state. Bhagavan is the highest substance, Madhva says, and moksha is reestablishing one’s lost relationship with Him.

The Advaitic view, which was so troubling to Madhva, leads the soul away from the world—for it is seen as false and illusory—and propels us toward an impersonal and indistinctive, transcendental Brahman, with which we merge in the final stage of moksha (liberation). At that moment, even our individuality is viewed as an illusion to be shed. We become the drop of water reuniting with the ocean, never again to be deluded by maya or our troublesome individuality. Due to Advaita’s prejudice against all distinctions, including individuality, its preferred process of evolution is jnana yoga or the cultivation of discrimination and knowledge of Brahman. This inevitably leads to less emphasis on karma, or action, and especially bhakti, or spiritual emotion combined with service.

For Madhva, the scriptures, the guru and the Lord in person, within the heart or as an avatar, are the various ways in which Bhagavan, the Absolute Truth, reveals Himself. In all these revelations the soul can only invite the appearance of the truth. Sincere individual effort in material acts is necessary, but ultimately the Supreme Person, Vishnu, reveals Himself when and to whom He chooses. But what is it that induces the Lord to reveal Himself, and what is the destination of the soul to whom He has been revealed?

Madhva’s Philosophy in Nine Tenets

From the Prameya Shloka, a summary of the tenets of Tattvavada written by Sri Vyasa Tirtha (1460–1539), a staunch and highly venerated Madhvite scholar and missionary

1. Hari (Vishnu) is Supreme.

2. The world is real.

3. The differences

are real.

4. The various classes of jivas are cohorts of Hari.

5. They reach different states (lower or superior) ultimately.

6. Mukti, liberation, is the experience of one’s own nature.

7. Mukti is achieved by pure devotion.

8. The triad of perception, inference and testimony are the sources of valid knowledge.

9. It is Hari alone who is praised in the Vedas.

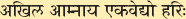

Having returned to Udupi from the Himalayas, Madhva is dictating to Satyatirtha the Sanskrit commentary on the Brahma Sutra that he divinely received from Sage Vedavyasa. Satyatirtha is scribing his master’s words on dried palm leaves. He will rub the leaf with lamp black to make the etching legible, then assemble the pages into a book, bound with a cord threaded through a hole in each leaf.

A. MANIVEL

Release Is the Attainment of Bhagavan

Madhva holds that nurturing the soul’s relationship with Bhagavan is the correct aim of yoga practice or the cultivation of knowledge. It is not seeking knowledge of the impersonal Brahman or trying to negate and relinquish one’s material identity that brings liberation, as Shankara would claim, but rather regaining the ability to see the transcendental form of Bhagavan face to face and then to render loving service to Him. Knowledge is not an end in itself; it is a means to awakening devotion.

In Madhva’s view, the real soul remains an individual after liberation and, in its spiritual body, resides in Vishnu’s eternal abode, where it is no longer subject to birth, death, old age or disease. Madhva quotes from the Brahma Vaivarta Purana, “Those who have attained final release assume, of their own accord, luminous bodies, and through them they enjoy only pure pleasures…. They are rid of all miseries, as well as all undesirable merit, together with demerit, and they are freed from all defects and consist only of intelligence, bliss, etc.”

This is radically different from the Advaitic view of liberation, to which such descriptions of the afterlife must simply be considered maya or illusion. Madhva argues that the scriptures abound in depictions of such spiritual places, which are real and eternal. Describing that transcendental world of bliss, he writes, “The liberated souls, having found their eyes and ears, loving one another, become hierarchically different in various qualities such as intelligence. Some among them play in the huge ocean of milk. Some play near and in the gardens. They bathe and behold themselves in deep, fine lakes fit to bathe in. They behold the Supreme Lord Himself.”

Genuine Worship

Madhva points out that while Shankara did institute among his followers a system of worshiping six Deities (Ganesha, Surya, Shakti, Siva, Kumara and Vishnu), the devotee is, in fact, told to use the image of the Deity only as a means to concentrate the mind on Brahman. The aim is to go beyond the form and merge with Brahman. The form is thus, in the worshiper’s heart of hearts, taken as an illusory tool only—a means to an end, namely the unmanifest, formless Brahman. This, to Madhva, is not true worship. For worship to be true, he declares, the forms of the worshiped and the worshiper must be accepted as real and eternal and linked in a favorable relationship. He delineates three grades of image worship. In the first, the Deity is regarded as illusory and only a means to an impersonal, formless end. In the second, worship is performed in order to receive temporary personal benefits. In the third and only recommended type, the Deity is adored in full faith, as the Supreme Being, Bhagavan Vishnu. On this point he quotes the Brihat Tantra: “Just as Shri (the Goddess of Fortune), though eternally liberated and absolutely accomplished, eternally contemplates Vishnu, so shall the devotees of Vishnu do the same.”

To Madhva, it is as subversive for the soul to claim that there is no Bhagavan, but only an impersonal-energy Brahman, as it would be for an ordinary citizen to claim to be the king. It is on this crucial point that the doctrine of bhakti rests. If the soul will not recognize that Bhagavan is a Person, or that He can come to Earth as an avatar if He wishes, or make Himself known in the scriptures or within one’s heart, and, most importantly, that He is Bhagavan, the possessor of all opulence, then how, Madhva asks, can one render genuine service to Him? And without rendering service, how could one ever become liberated from ignorance and bondage? The world is, in fact, a jail full of rebellious souls who refuse to recognize the greatness of the Supreme Being. The Advaitin’s idea of becoming Brahman at the point of liberation is, to Madhva, the ultimate act of envy and hostility toward Vishnu.

Madhva quotes from the Mathara Shruti, “Devotion alone leads one to the Supreme; devotion alone shows Him; in the power of devotion is the Person. Devotion only is the best of means.” He writes, “The voice of the clouds, the music of the spheres, the fury of the winds, the roar of the ocean waves, the names of the Devas and the sages are all names of the Supreme, giving voice to His eternal glory and majesty.”

Madhva deeply valued diligent scholarship and study of scripture. In this regard he quotes the Brahma Taraka: “Only on the proper study and understanding of all the Vedas, supplemented by a study of the Itihasas (Ramayana and Mahabharata), Puranas and the doctrines of logical principles guiding their interpretation (Mimamsas), is the knowing of Vishnu possible, and not otherwise.”

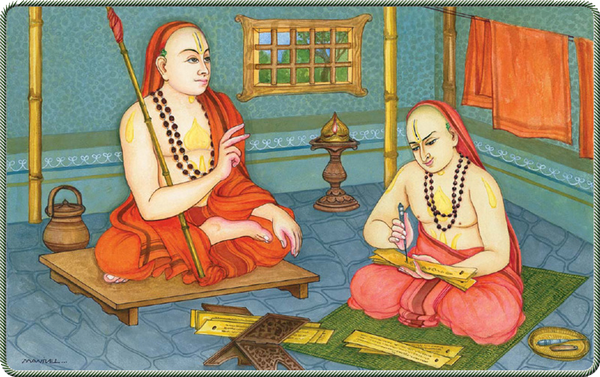

Inside the Krishna Matha, Madhva’s central monastery in Udupi, the guru gives a discourse on his philosophy, which he calls Tattvavada, “doctrine of truth.” His right hand displays the classic mudra by which he indicates, “Difference is real; difference is real; difference is real,” which is the essence of his doctrine.

A. MANIVEL

Final Distinctions

Madhva’s view culminates in the belief that our individuality never had a beginning and never ends. Differences or distinctions are not only real and eternal, but vital in that they convey to us the unique nature of all that exists. In spite of the fact that we are not and can never be supremely powerful, knowing and beautiful, we are so intrinsically unique and individual, that through our desire and actions we can inspire the Supreme Being to engage us in an intimate, loving relationship. Hindu holy texts abound in ideal paradigms: the friendship of Arjuna or Draupadi, the service of Hanuman, the parental love of Yashoda and Dasarath, the conjugal love of Sita, Rukmini or the all-consuming devotion of Radha and the Gopis, the unswerving devotion of countless beings sung of throughout the scriptures. All these give credence to Madhva’s thesis—that devotion, love and service are a path of eternal and joyous existence.

Conclusion

That, in brief, is the Vedantic thesis of the irrepressible Madhvacharya, one of the great saints of Indian history. Monumental doctrines have been created by many other saints: Tirumular, Ramanuja, Chaitanya, Vallabhacharya, Nimbarka, Vasugupta, Basavanna, Meykandar, Aghorasiva, Gorakshanatha, Srikantha, Swaminarayan and others. Their insights and debates are all gifts to humanity’s search for truth and spiritual liberation.

The magnificence of our Hindu dharma is that such great thinkers have delineated these philosophical points so keenly, creating a map of consciousness that followers may employ to discover for themselves what is real, unreal and relatively real. In our Hindu dharma, each seeker is free to decide which of these or other views he accepts, which inspires his heart and lights his path. What a marvelous diversity and arena for exploration Hindu dharma provides!