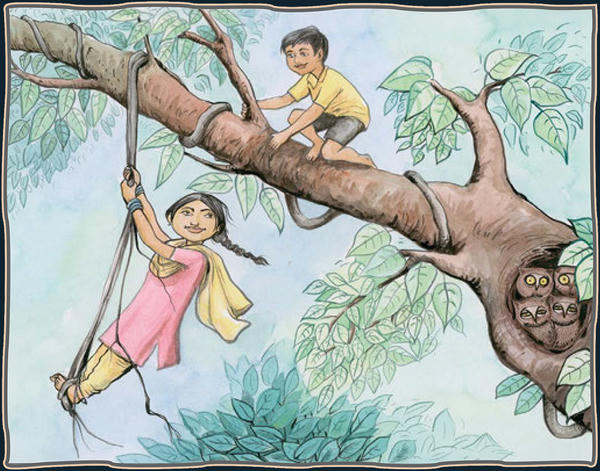

As her brother watches protectively, a young girl swings on a vine, restrained from falling as surely as the moral restraints of avoiding misdeeds keep us from falling from the yoga path. Like the silent witness within, a family of owls watches wisely from their nest in the tree.§

It is true that bliss comes from meditation, and it is true that higher consciousness is the heritage of all mankind. However, the ten restraints and their corresponding practices are necessary to maintain bliss consciousness, as well as all of the good feelings toward oneself and others attainable in any incarnation. These restraints and practices build character. Character is the foundation for spiritual unfoldment.§

The platform of character must be built within our lifestyle to maintain the total contentment needed to persevere on the path. The great ṛishis saw the frailty of human nature and gave these guidelines, or disciplines, to make it strong. They said, “Strive!” Let’s strive to not hurt others, to be truthful and honor all the rest of the virtues they outlined.§

The twenty restraints and observances are the first two of the eight limbs of ashṭāṅga yoga, constituting Hinduism’s fundamental ethical code. Because it is brief, the entire code can be easily memorized and reviewed daily at the family meetings in each home. The yamas and niyamas are cited in numerous scriptures, including the Śāṇḍilya and Varāha Upanishads, the Haṭha Yoga Pradīpikā by Gorakshanatha, the Tirumantiram of Rishi Tirumular and the Yoga Sūtras of Sage Patanjali. All of these ancient texts list ten yamas and ten niyamas, with the exception of Patanjali’s classic work, which lists just five of each. Patanjali lists the yamas as: ahiṁsā, satya, asteya, brahmacharya and aparigraha (noncovetousness); and the niyamas as: śaucha, santosha, tapas, svādhyāya (self-reflection, scriptural study) and Īśvarapraṇidhāna (worship).§

Each discipline focuses on a different aspect of human nature, its strengths and weaknesses. Taken as a sum total, they encompass the whole of human experience and spirituality. You may do well in upholding some of these but not so well in others. That is to be expected. That defines the sādhana, therefore, to be perfected.§

The ten yamas are: 1) ahiṁsā, “noninjury,” not harming others by thought, word or deed; 2) satya, “truthfulness,” refraining from lying and betraying promises; 3) asteya, “nonstealing,” neither stealing nor coveting nor entering into debt; 4) brahmacharya, “divine conduct,” controlling lust by remaining celibate when single, leading to faithfulness in marriage; 5) kshamā, “patience,” restraining intolerance with people and impatience with circumstances; 6) dhṛiti, “steadfastness,” overcoming nonperseverance, fear, indecision, inconstancy and changeableness; 7) dayā, “compassion,” conquering callous, cruel and insensitive feelings toward all beings; 8) ārjava, “honesty, straightforwardness,” renouncing deception and wrongdoing; 9) mitāhāra, “moderate appetite,” neither eating too much nor consuming meat, fish, fowl or eggs; 10) śaucha, “purity,” avoiding impurity in body, mind and speech.§