Chapter Thirty

Harnessing a Hurricane

On September 11, 1992, Hurricane Iniki struck a direct hit on the island of Kauai. The eye of this Category 4 hurricane went right over the monastery. Great damage was wrought by that storm. Three monastery buildings were destroyed, along with 10,000 trees and plants. It was months before electricity and running water were restored. That was a great challenge to the monks. But Gurudeva took it all in stride. He saw Siva at work even in this tragedy. He had the monks bake bread each day and take it, along with fresh cow’s milk, to the neighbors, who were stranded at home since all the roads were blocked. Gurudeva laughed and made the experience a positive one, which was amazing since the destruction and the disruption was so severe. It was a lesson to all the monks, a reminder and a living example of Gurudeva’s teaching that it is not what happens to us in life that matters, it is how we react, how we respond. And he responded to disaster with grace, turning the devastation of the monastery he had worked a lifetime to create into an ingenious way to preserve it forever.§

It happened like this. When, months later, the monastery received the woefully inadequate insurance check for $300,000, Gurudeva refused to cash it, but kept it in his room and meditated on its best use. After a few days, he told the monks that he was putting it all in the bank, and that not a penny would be spent. That fund would earn interest that could be used to repair the damaged monastery. It might take ten years, he said, but at the end of that time all the facilities would be restored, and the $300,000 would still be intact. §

It was a brilliant move, and it taught the monks about the power of endowments. Gurudeva worked with Paramacharya Bodhinatha, his senior disciple, to create a unique financial institution, Hindu Heritage Endowment (HHE), officially founded in 1994. As of 2011, HHE has over 80 funds and $10 million in assets, helping orphanages, temples, swamis, ashrams and publications around the world. Turning a natural disaster into a global service institution typified the way Gurudeva worked with energy, transmuting it for a higher purpose. §

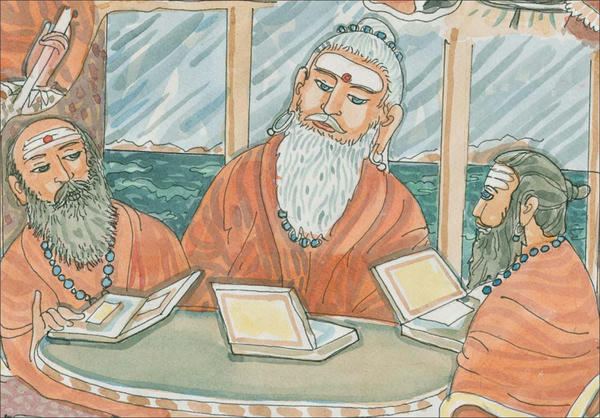

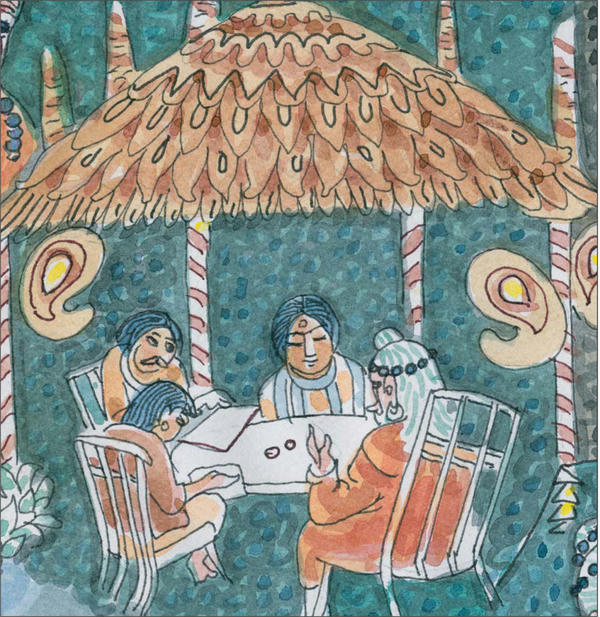

Gurudeva was engaged in every aspect of his mission, knew every detail, approved every budget. He held weekly stewards’ meetings with his senior monks, often at seaside hotels, to keep an overview of his global mission.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •§

As I see it, everything that was strong survived, and everything weak was destroyed in the face of wind gusts measured at 194 miles per hour at the Kauai NASA station. The whole island was engulfed and few escaped damage.§

What is to be done with all this energy? From a mystical point of view, external or internal, negative or positive, energy can be run through the converter named jnana (wisdom) and turned into a creative force. At our spiritual center, we put most of ours into newer and bigger and better publications, including HINDUISM TODAY.§

The scriptures say adversity makes strong men stronger. It is always best to face adversity and success in equanimity, and we have to confess we enjoyed fetching water in buckets, beating our clothing on a rock by the river and cooking over an open fire. All these simple joys reminded us of the many times that our swamis lived the village life on the Jaffna peninsula.§

Gurudeva founded Hindu Heritage Endowment as an independent public service trust to provide Hindu institutions with permanent, growing income through charitable endowments. He secured from the IRS a special ruling allowing that beneficiaries can be anywhere in the world. This enables wealthy Hindus in America to support their village temple in India, for instance, and receive a US tax deduction. He was not planning just for his own institution’s future, but the future of every Hindu institution in the world. §

Each quarter from 1994 to 2001 Gurudeva met for a day at the posh Princeville Hotel with HHE’s monastic stewards to monitor the funds, expand their capacity and refine their uses. HHE ultimately became a primary supporter of his monastic order and Iraivan Temple, fulfilling Gurudeva’s vision of self-sufficiency. §

All the guardian devas of all the people in the beneficiary organizations and of all those who set up the endowment are involved in the HHE. It is a devonic creation, not forged by us, but bequeathed upon us from the Devaloka and the Sivaloka to fulfill a need. The guardian devas of each organization have a personal interest in Hindu Heritage Endowment because they are putting all their energy and thought into creating for each Hindu organization a permanent financial abundance so that its leadership can concentrate upon fulfilling its goals rather than on constant fund-raising and basic concerns about money. §

Power of the Press

From the beginning, writing and publishing were the cornerstone of Gurudeva’s spiritual mission. He understood the staying power of the written word and knew that every spiritual tradition rests on a bedrock of holy texts. But the extensive travel of the late 70s and early 80s had kept him on the road and away from the philosophical writings that he so loved. His work with HINDUISM TODAY magazine never ceased, though; and his marvelous upadeshas given all over the globe during this hiatus were captured and saved for future publication. §

The late 1980s and the 90s were that future—a return to earlier times when he published with great energy and enthusiasm. But technology had evolved; and he inspired his team to immerse themselves in state-of-the-art digital publishing, including multimedia CDs, audio, video and computer graphics. He introduced his daily Hindu news service, called Hindu Press International (HPI), using the Internet to connect and inform Hindus. By then he had become accustomed to the radical conceptual change that the Internet had conjured. §

With the help of that marvelous technology, Gurudeva developed an editing style that was ingeniously, perhaps uniquely, collaborative, using networked Macintosh computers. Each afternoon, 365 days a year unless he was traveling, he met with a team of two, and later three, monks between 3 and 7 pm. The team’s portable Macs were connected so that the same document, say a chapter of Loving Ganesha, was displayed simultaneously on all monitors. When any member of the team made an alteration, all monitors were updated instantly, in real time. No more scribbling down dictation on paper, to be typed up and brought back for review the next day. §

Gurudeva never wrote a book in the usual way. If he wasn’t working from the transcript of a talk he had given, he would come to the table with a topic he had meditated on that day, and typically begin by dictating a page or two as one of the monks captured it onscreen. Then he would invite them to dive in and edit the pages. “Open season,” he would announce, and together they would all work on bringing it, as Gurudeva often said, “from talkenese into the English language”—though all this was done with the greatest caution to preserve the power of the original expression. When working with talks that were given in the 50s, 60s and 70s, from which many chapters of his Master Course trilogy were sourced, every effort was made to undo unnecessary editing that had occurred in earlier days and restore the original upadesha. §

It often took hours to edit just a few sentences. But as in all he did, Gurudeva never rushed, never felt the weight of time. He was after quality; and if it took three hours to craft a sentence, he would rejoice in the accomplishment at the end. In the creation of the 365 sutras of Living with Siva, an average of two or three sutras were edited, discussed and finalized each afternoon—though even those crafted to perfection were often re-edited a week later, and again the next month. §

In writing Dancing with Siva, the challenge was to condense oceans of information into a single page for each topic. Gurudeva took special delight in following his self-imposed discipline for the pages of this book, which decreed that the questions and answers be exactly the same length, each character of each word fine-tuned so that every shloka and bhashya fit in exactly the same amount of space. §

Gurudeva loved to meander in the monastery’s sacred gardens. These solitary walks almost always had a purpose, and he often returned with new insights, ideas and plans for the future to share with the monks.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •§

Adding to that challenge, a workflow evolved in which the team researched, wrote and refined the text, then—when it seemed as though it were perfect and complete—asked, “What more needs to be explained here?” If they unearthed a vital addition, even one that seemed impossible to incorporate, they would churn and distill the words down even further, to the most condensed summary imaginable, magically adding perfection to perfection. It was not easy, but these requirements brought forth an uncommon clarity and a density of meaning rarely achieved, except by gifted poets. §

Gurudeva looked forward to these sessions every day, preparing subjects and calling upon the inner forces, his team of devas, to assist in bringing forth the powerful, insightful writings that would guide devotees into the future of futures, writings that would last for millennia.§

Every word, every phrase, every punctuation mark passed by his careful eye; and only when he was truly satisfied would the team move on. Though he typed only occasionally in those sessions, he would freely break in to type or voice a clarification or answer a question about the wording of a passage. This often led to unpredicted new insights. If research was required, as it not infrequently was, he directed the swamis to gather information during the next day for their afternoon session together. In these days before Google, this entailed old-fashioned forays into the monastery library or emails to knowledgeable sources. §

So disciplined was Gurudeva’s editing routine that Church members in the neighborhood could look out their window at exactly the same time each afternoon and see their satguru heading off for his editing session. For years, he worked in several of the coastal hotel lobbies. The staff loved him dearly and always felt special blessings were in store for the evening if he came to their place. They did not know his reasons for leaving perhaps the most beautiful place on Kauai to meet at their hotel. He had tried to edit in his office, but his mind was not free, and the interruptions were constant. §

When asked if the many sounds around him in the bustling restaurant area were disturbing, Gurudeva responded, “Not at all; noise makes me quiet!” It did perplex some of the monks how noise could make one quiet, how being in the rather worldly vibrations of a hotel lobby could be a catalyst for creative, inner writing. It was no mystery to the master. Like Yogaswami, who almost daily walked the swarming streets of Jaffna, and Chellappaswami, who lived for years in front of a tumultuous temple, Gurudeva had experienced the effect of contrast, the clash of the inner and the outer states of consciousness which, for him, brought forward the subtle in contrast to the gross, shone a light on light, exactly because of the surrounding shadows. Without the grounding, the anchor which the noises and the people and the swirling karmas provided, the inner states of mind dominated and he grew too remote, too refined to bring the teachings forth. §

Here, near the ocean, he could work for hours with few intrusions, unencumbered by the weight of his many responsibilities as satguru and the minds of hundreds of devotees. The most innocuous five-minute disruption at the monastery could result in an hour of thought about the issue. His seaside work was efficient, focused and free-flowing. A glass of wine or two through the afternoon made for a relaxed and joyful session and, as Gurudeva said, subdued the conscious mind, allowing the superconscious mind to flow through and guide the work. He reflected that this was akin to great Japanese poets for whom sake is a linguistic elixir. §

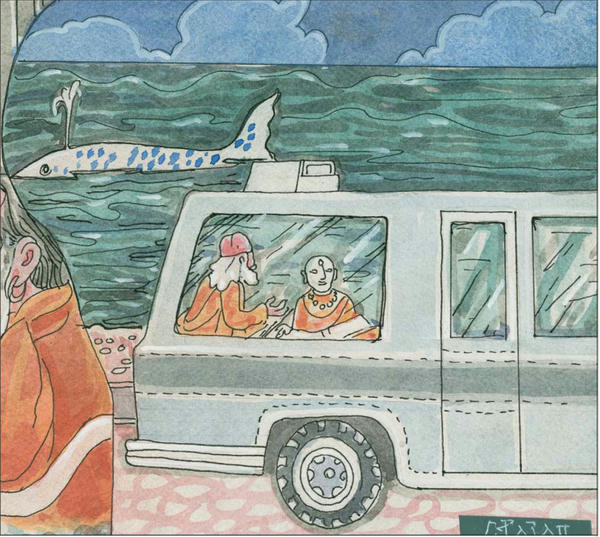

For a few years Gurudeva did his daily editing near the ocean in a specially outfitted Winnebago Rialta. The editing team, working at a table in the back, had a view of turtles and whales.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •§

When Hurricane Iniki shut down all but two of the island’s four dozen major hotels in 1992, Gurudeva flew to California with the editing team and continued the work in hotels there for three months. Before returning to Kauai, he went shopping one afternoon for a used RV. He found one he liked, a 1979 Winnebago, and had it shipped to Kauai for the afternoon sessions. Refurbished by the monks, it became his creative headquarters on most days, parked twenty yards from the sea at Kealia beach. In the winter months, he enjoyed watching the whales and green turtles frolicking off the reef. On the day he completed Dancing with Siva, a massive male whale breached a hundred yards off shore, then forcefully flapped his twelve-foot-long fin twenty-seven times on the water, as if celebrating the event. Seeing this, Gurudeva commented that the book’s creation was driven by “whale power.” §

An early adopter of cell phones, Gurudeva kept his on the table during every editing session. His close devotees around the world all had his personal number, which spelled out “New Deli.” Hardly a day would pass without a call from some far land—someone’s father had died, someone was elected to parliament, a baby was born that morning. Gurudeva never once hesitated to interrupt his session to take a call. If it was a serious one, he would get up and walk in the hotel garden as he counseled and consoled his shishyas. Then he would return and invariably know the next word of the next sentence on the screen. §

When he dictated, and sometimes he did the typing himself, it was often as if he were hearing an inner voice. When the monks with him complimented the wondrous words that had poured forth during those surges, he would quip, “I have good writers upstairs.” During this torrential, two-decade-long, computer-assisted transmission of spiritual insight, Gurudeva methodically assembled the fruits of fifty years of sadhana and ministry to create his philosophical, cultural and spiritual legacy.§

His books were vast, diverse and always focused on deepening everyone’s understanding of Hinduism, and always in an approachable and practical idiom. In his last ten years the book effort took on a new momentum as more and more people realized their preciousness. Spanish-speaking readers wanting to share the teachings received permission to translate the works. A team in Russia published editions, as did others in Sri Lanka (Tamil), Mumbai (Marathi), Kuala Lumpur (Bahasya Malay) and elsewhere. Motilal Banarsidass, Munshiram Manoharlal and Abhinav, three of Delhi’s foremost publishers, vied to reprint his books in India. Each firm was given rights to certain books.§

A Heart for Art

Gurudeva understood the importance of art in communicating ideas and uplifting the human spirit, and he regarded Hindu art as itself sacred. During his travels, he noticed that art, like so many other aspects of Hinduism, was waning, with unappreciated artists urging their sons to be engineers. In response, he sought out the finest artists and commissioned them to do major works in traditional styles, paying them well for their gifts. Artists in India, Bali and North America took on creative projects, some involving years of painstaking work on a single canvas, others requiring hundreds of large paintings illustrating Hindu motifs. §

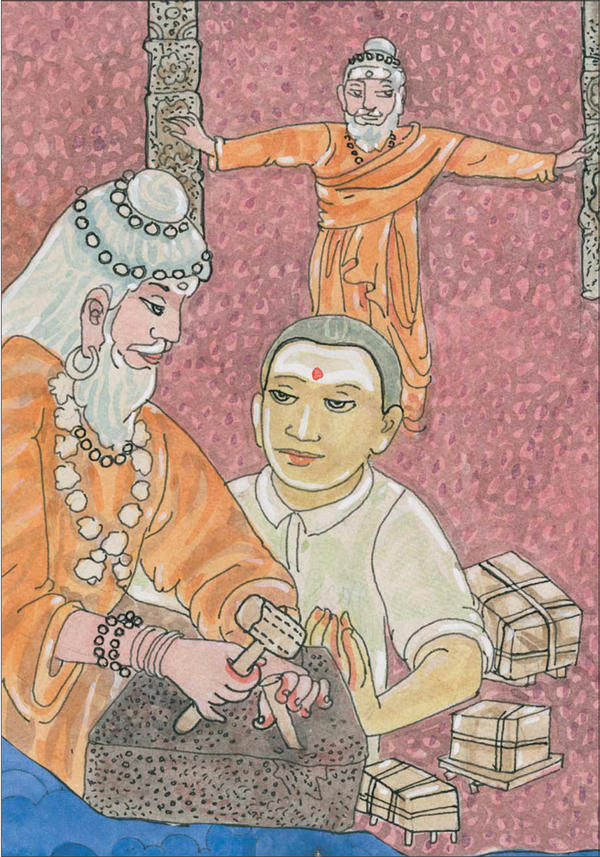

Art is more than painting, and Gurudeva retained bronze and stone craftsmen to produce Saiva saints, Siva’s 108 dance poses, a 32,000-pound Nandi and a 12-foot Dakshinamurti. Artists were awed by the Hawaii swami’s interest in their skills. Traditional artists A. Manivelu and S. Rajam spent years of their lives illustrating his publications. After Gurudeva purchased his lifetime collection, which was decaying in a Madras closet, the elderly S. Rajam wrote, “To take my 400 paintings to his ashram in Hawaii is something that opened my heart, to know there is a future for my paintings. Above all, his very majestic personality reminds artistes like me of old-time rishis and religion-makers.”§

Writing a Modern Shastra

Having completed, with his editing team, the Nandinatha Sutras, answering in writing, once and for all, the many questions he had been asked over and over for decades by followers wanting to know his views on myriad life issues, Gurudeva devoted the full year of 1994 to what he humorously called “the world’s most boring book, or the best remedy for insomnia:” Saiva Dharma Shastras, The Book of Discipline of Saiva Siddhanta Church. §

He carefully timed its publishing to coincide with the date of the retrospective perspective the devas took when writing The Saivite Shastras, which he clairvoyantly read in 1973 from the oversized, white inner-plane book that a group of three devas wrote to guide his order into the future. They had done this by projecting themselves into the future to the year 1995 and writing their superconscious history of what Gurudeva and his order did, or would do, up until that time. Like the words of fortune tellers, the pages of their book not only painted a picture, they carved a path, influencing and coloring for Gurudeva and his monks what was to come, what they would do and how they would do it. For 25 years he had followed that angelic prophecy, and now it had arrived. §

Gurudeva shared his perspective in the book’s introduction:§

As this year, 1995, unfolds, the past has met the present, and it is truly a glorious time, because I can now add to the great inner-plane manuscripts first read from the akasha in 1973 these Saiva Dharma Shastras, the story of our contemporary Church’s ideals, day-to-day customs and procedures. Lemurian Scrolls and these Saiva Dharma Shastras are the legacy I leave my acharya successors, their guidelines and firm laws, their commission to follow and fulfill, along with The Master Course trilogy—Dancing, Living and Merging with Siva, and Shum, the language of meditation. Our pattern has been completed, the prophecy manifested better than any of our expectations. We are eternally grateful for the untiring help the Gods, devas and rishis have provided ever since the Lord Subramaniam Shastras were revealed, a profoundly needed message from the past for the present, now preserved for the future. §

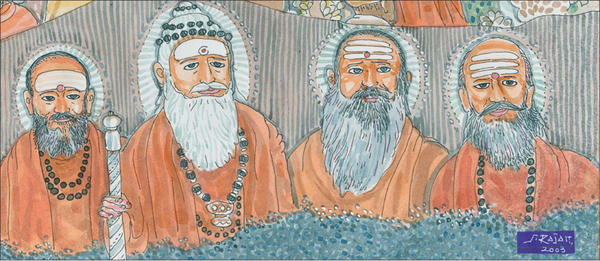

Saiva Dharma Shastras, the seventh or eighth church manual Gurudeva had written, drawing on aspects of the American church system, was crafted to assure his organizations’ social viability and structural integrity. In its pages he finalized patterns for the future, including the extended family structure for his missions, and he designated as his successors three of his senior monastics: Acharya Bodhinatha Veylanswami, to be followed by Acharya Sadasivanatha Palaniswami and then Acharya Sivanatha Ceyonswami. §

For decades Gurudeva worked closely with his senior acharyas to guide the Church’s global mission. In 1995 he declared they would succeed him in order: Bodhinatha Veylanswami, Sadasivanatha Palaniswami and Sivanatha Ceyonswami.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •§

My acharya successors will have a momentous task, to be sure. They who have striven so hard to fulfill their holy orders of sannyasa will have these Saiva Dharma Shastras, the Lord Subramaniam Shastras and the Mathavasi Shastras as their discipline, their sadhana and, yes, sometimes their tapas. As the future is based upon the past, this recorded past within these Shastras releases new energy. §

As predicted in The Saivite Shastras, by 1995, the year we are in now, our pattern is set, and constant preservation and perpetuation is commissioned by me and by the inner worlds for its fulfillment generation after generation for over a thousand years into the future of futures, for ever and ever. Yea, much longer than that, much longer than forever, for these Shastras give the explanation of life as it is to be lived and has been lived by a healthy, happy, spiritually productive, small inner group and larger outer group, both ever growing in strength and numbers.§

A South Indian Temple in Hawaii

Sivalaya Dipam in 1991 proved prophetic. On that rainy December afternoon, the monks and two dozen members held a homa in the Agni Mandapam. As decreed by tradition, an enormous fire was built in an open field nearby where the far-swirling sparks from bamboo and logs could fly freely and safely, an intense bonfire to represent God Siva as a pillar of flames. Gurudeva arrived after dark in his Winnebago Rialta, having just come from his afternoon editing session. It had been raining for days, and the ground was so soaked that it couldn’t hold another ounce of water. §

Throughout the 90s Gurudeva visited India often, working on the ever-evolving Iraivan Temple details. On December 21, 1990, he chipped the first stone in an elaborate ceremony at Kailash Ashram in Bangalore.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •§

As Gurudeva descended from the vehicle in his dapper, orange Indian kurta outfit, monks and devotees huddled under umbrellas greeted him warmly. But instead of sitting for the rites as he did each year, he slowly trudged around the blazing fire, as if entranced, then stopped in his tracks and prostrated in the mud, worshiping the fire that stood for the infinite Siva. It was a rare thing to see the satguru on the ground, prone, out in a field. No one knew in that moment that this would be the exact spot on which Iraivan Temple would rise. Superconsciously, Gurudeva must have known, though he never spoke of it. §

It would happen again. In 1994, in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada, Gurudeva was visiting the committee of an incipient Ganesha temple. Four years before, he had instructed them to buy a “beautiful piece of land, at least five acres, with a knoll and a stream on it.” They since had found the land, and Gurudeva was setting foot on it for the first time. §

Instead of entering the little house where Lord Ganesha was temporarily enshrined, he walked around the structure and then, to his hosts’ puzzlement, headed out into the pathless woods. Followed by less fleet devotees, he strode through brush and brambles with an intent that defied reason. Suddenly he halted, and they caught up in time to witness him prayerfully holding a handful of flowers with which they had greeted him. Placing the flowers on the ground where he stood, the satguru prostrated in the woodsy dirt. §

The significance was not lost on the temple hosts, who the next day hired a surveyor to mark the place where those blossoms were offered. In the coming years, the Edmonton Maha Ganapathy Temple was built upon that now holy site. Twice Gurudeva prostrated on virgin land, and twice temples arose on the spot. §

Between 1975 and 1990 Gurudeva had been working to bring Iraivan Temple to the Earth plane. Roads were built, lands cleared, mortgages paid, the crystal Svayambhu Lingam acquired and master plans drawn by architectural firms. In 1982 Gurudeva visited the famed Mahabalipuram College of Architecture and Sculpture and met the rising Sri V. Ganapati Sthapati, who would soon become one of Bharat’s foremost temple architects. Honored with the coveted Padma Bhushan award in 2009, in recognition of outstanding civilian service to the nation, this gifted master builder would design Iraivan in the style of his ancestors. §

It would be a granite edifice, in the tradition of the ancient citadels of Tamil Nadu’s Chola Dynasty, famed for their elegant beauty and remarkable sculptural craftsmanship. Its name, too, harkens back to that era. Iraivan is an ancient Tamil name for God, an endearing appellation that describes Siva as “He who is worshiped.” In this Hawaiian home for God Siva, every stone would be sacred, each piece a part of the body of God, carved in the old ways, by hand, by craftsmen of an art that was on the verge of dying out, like many in our modern age. §

By decreeing that this temple be made without the efficiencies of electric or hydraulic tools, Gurudeva assured two things: first, that it would reflect the best of human skill, since hand sculpting is vastly more refined and subtle than works crafted by modern machines; and, second, that at least one more generation of stone carvers would become proficient in the craft, which is passed down from father to son, artisan to apprentice. §

Even in India nowadays, temples are rarely built entirely of stone, and never in this time-consuming and expensive, traditional manner. Modern contractors opt for concrete and brick for structural work and power tools for stone shaping, which cannot compare to carving. It may well be, and only history knows for sure, that Iraivan Temple, carved between 1991 and 2017 in Bangalore, India, is the last temple created completely by hand in India, with a primitive coke-burning forge and just two simple carving tools—a bamboo-handled hammer and hand-forged chisels of mild steel. §

Gurudeva worked daily on the details of the temple. He also engaged his monks and all of his shishyas in its creation, knowing that this massive undertaking would define their shared goals and bring them together. He often described its import:§

As I look into the future, I see Iraivan, fully completed, as a center where devotees will come to find the center of themselves. We will preserve it and maintain it so that it is the way Rishikesh used to be, a proper, pure, quiet place where devotees can go within themselves through the practice of yoga. There are very few such places left on the Earth now. Kauai’s Hindu Monastery is one of them. I see Iraivan as a yoga citadel, a place of pilgrimage for the devout, sincere and dedicated. I see Iraivan as India’s message to the world on visitors’ day, when Hindus and non-Hindus alike come to admire the great artistry of the silpi stone carving tradition. I see Iraivan as a fulfillment of our lineage, our scriptures and our monastery. This is a place where you do not have to invoke God, for God is here, for this is where heaven meets the Earth.§

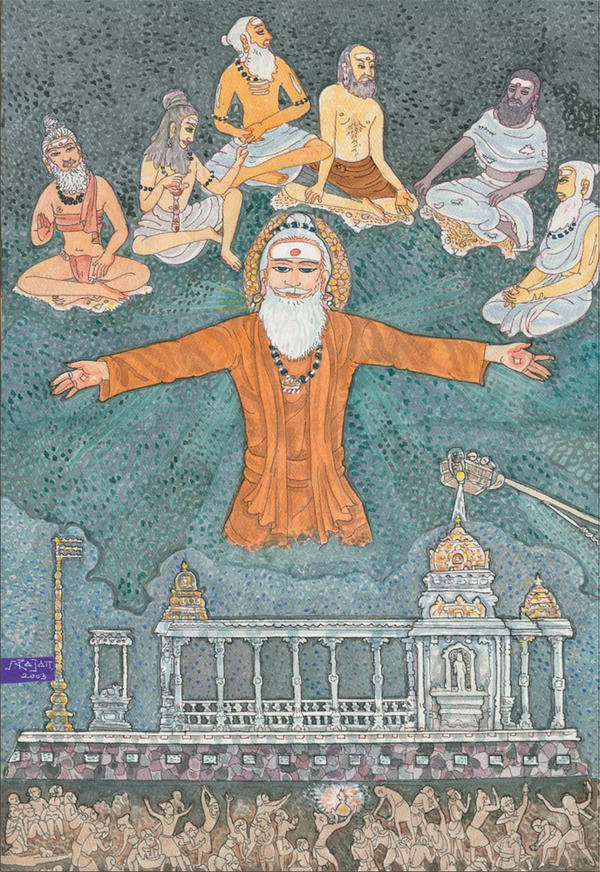

Artist S. Rajam envisions the auspicious day when thousands gather on Kauai for the consecration of Iraivan Temple. As holy waters are poured over the vimanam, Gurudeva blesses from his world of light, surrounded by the gurus of the Kailasa Parampara.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •§

Help from His Indian Brothers

Faced with the daunting task of constructing a granite temple in India and having it shipped to Kauai piece by piece, Gurudeva made inquiries as to who in that great land might facilitate the effort for him, 8,000 miles away, where a contract is less the end of negotiation than the beginning of further discussion. Who had the experience, expertise and grassroots contacts that would be needed? He was directed to Tiruchi Swami, who not only agreed to meet with Gurudeva but insisted on hosting at his ashram for two days the thirty pilgrims who were traveling with him on the 1990 Indian Innersearch. §

Tiruchi Swami was a white-robed saint based in Bangalore, a rare mystic, born in 1929, just two years after Gurudeva came into this world. The story is told that, while traveling in Kanyakumari in South India, his parents were informed by a stranger near the Devi temple, “By the grace of the Divine Mother and Lord Subrahmanya, a glorious son will be born to you. He will be a teacher and benefactor for all mankind.” The prophecy proved true. In his twenties, around the same time Gurudeva received his ordination in Sri Lanka, the young seeker trekked to Nepal where he was initiated. Sri Tiruchi Mahaswamigal (1929–2005), or Tiruchi Swami, as he is known, was instructed by his guru, Shivapuri Baba, to return to India, propagate dharma and build a temple. Before returning, Swamiji went to Mount Kailash. There, he had a vision of Goddesses Durga, Lakshmi and Saraswati, who told him to go south, to Karnataka. §

In 1960, while traveling, Swamiji had a divine vision that inspired him to start an ashram and temple near Bangalore, three years after Gurudeva founded his first center in San Francisco. His Kailash Ashram and Rajarajeshwari Temple, where Gurudeva would sojourn many times, were the fulfillment of those inner orders. These two great gurus and their successors would be profoundly connected, their lives interwoven. §

With Sri Tiruchi Swami’s guidance and practical engagement, the plan solidified, obstacles were overcome and Gurudeva chipped the first stone for Iraivan in a grand ceremony at the Rajarajeshwari Temple. With that, Gurudeva flew back to Kauai, leaving two of his swamis in India to complete the protracted contract negotiations with Ganapati Sthapati.§

Sitting on the banks of the Wailua River, Iraivan temple’s golden towers would, in the years to come, draw devotees from around the world. The 12-foot-tall stone Dakshinamurti sits silently nearby as the monks approach in procession with drums and conches.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •§

Earlier, while the Innersearch pilgrims were in Madras, Gurudeva rode by car with three of his monks to personally carry the blueprints of Iraivan Temple to another of India’s greatest saints for blessings. Arriving in Kanchipuram, they waited in the standing queue for darshan of Sri la Sri Chandrashekharendra Saraswati, then 97, the senior pontiff of Kanchi Kamakoti Pitham. Devotees filed by, receiving blessings from the frail sage who, drifting in and out of consciousness, lay on a simple white canvas cot. At his side, assisting in this sacred daily routine, was his successor, Sri Jayendra Saraswati, shaven headed, graying, intense and serious. Alerted to Gurudeva’s impending visit, he greeted the tall, orange-robed American sage with respect and asked to see the temple plans. Quickly they were rolled open on the table that separated the Vedanta monks from the line of devotees. Jayendra Saraswati then whispered in the ear of his senior, “The swami from Hawaii has arrived.” §

Suddenly the sage became conscious, wide awake, and asked to be propped up on the cot. His big doe eyes met those of Gurudeva. Moments passed. The sage saw the papers, placed his hand on them, then eased back down on the cot and closed his eyes. Jayendra Saraswati asked about the temple and listened raptly as one of Gurudeva’s monks who spoke Tamil gave details of the project. Jayendra Saraswati, too, blessed the plans, then posed for a photo with Gurudeva, whom he had met twice before. “The deed is done,” Gurudeva remarked as they exited the ancient stone chamber and reemerged into the light of day.§

Back in Bangalore, discussions centered on a carving site, for a Hindu temple made of stone is built in a special and unusual way. An entire village would have to be created, including housing for 75 sculptors and their families, gardens for their food, wells dug for their water, blacksmith forges and carving sheds, plus facilities for managers. Where would all this happen? §

Fortunately, Sri Balagangadharanathaswami of Adichunchanagiri Mahasamsthana Math, who received his training at Kailash Ashram, was told of the need and offered eleven acres of arid land for the project, at no cost. It was an enormous boon, and within months the worksite that would continue for several decades was completed. Having the carving site near Bangalore was critical, as the Indian swamis there could keep close watch over the construction process as Gurudeva’s representatives. They looked after his project as if it were their own, and looked after him with unfettered affection and unlimited assistance. They were, to be sure, the key to Iraivan’s manifestation.§

Five Holy Bricks

Iraivan Temple, Gurudeva proclaimed, would be India’s gift to the Western world. Gurudeva named 1995 the Year of Iraivan Temple. To rally the forces necessary for this prodigious effort, he flew the monks from outlying monasteries to Kauai, bringing his entire order together for the first time in forty years. §

The event that catalyzed the monks’ homecoming was the elaborate two-day Panchasilanyasa Puja, a ceremony to sanctify the foundation and begin the building of Iraivan Temple. About 200 devotees from around the globe came to witness the placement of five bricks in an underground crypt, along with a cache of gems and other treasures. Warm Hawaiian breezes enveloped the faithful in a gentle embrace. Camphor, incense and flowers spoke to their senses, as did the tintinnabulation of bells and the sonorous Sanskrit chanted loudly by vibhuti-smeared priests. Deva Rajan shares his experience of the event:§

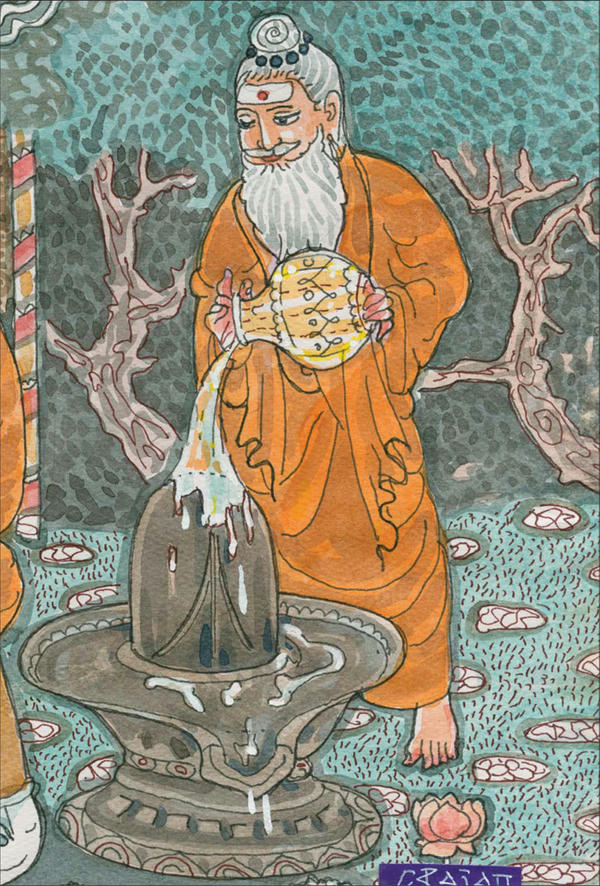

When a North Indian Narmada Lingam was gifted to the monastery, Gurudeva invited pilgrims to perform abhishekam on the sacred stone and occasionally bathed the Sivalingam with stream water himself.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •§

Many priests were there from Chennai for the homa, including the respected Sivasri Sambamurti Sivachariyar, who officiated the Hindu rituals, along with architect V. Ganapati Sthapati. A four-by-four-by-four-foot square pit had been dug at the northeast corner of the future inner sanctum of the Iraivan Temple. In the pitch black of the hours before dawn, no one could tell if we were in India or in Hawaii. With great ceremony, my Gurudeva, the Hindu priests, the architect and others installed sacred substances into the pit—gems, gold, silver, rare herbs and other auspicious items. Tray after tray was carried by the monks to be placed. At one point, a large pot of vibhuti was poured into the pit; hence any further offering drew clouds of vibhuti floating out of the hole, blessing us all.§

Under the tranquil light of the moon, Sambamurti Sivachariyar, together with Gurudeva, frequently waved the glowing camphor flame. In bursts of powerful sacred chanting, the pit was consecrated. Master architect Ganapati Sthapati placed five sacred bricks engraved with the letters Na Ma Si Va Ya in Tamil.§

After these rich and abundant blessings, Gurudeva directed a few of us to seal it all off with concrete. As the crowd dispersed, we mixed several wheelbarrows of fresh concrete and poured it into the pit. When the task was complete, with joyous hearts we drifted away, knowing we had participated in a rare and magical event that would stay with us forever.§

In the years that followed, Gurudeva met a thousand times with the various teams building the temple, following every detail. He would live to see only the first three courses of the sanctum in place. §

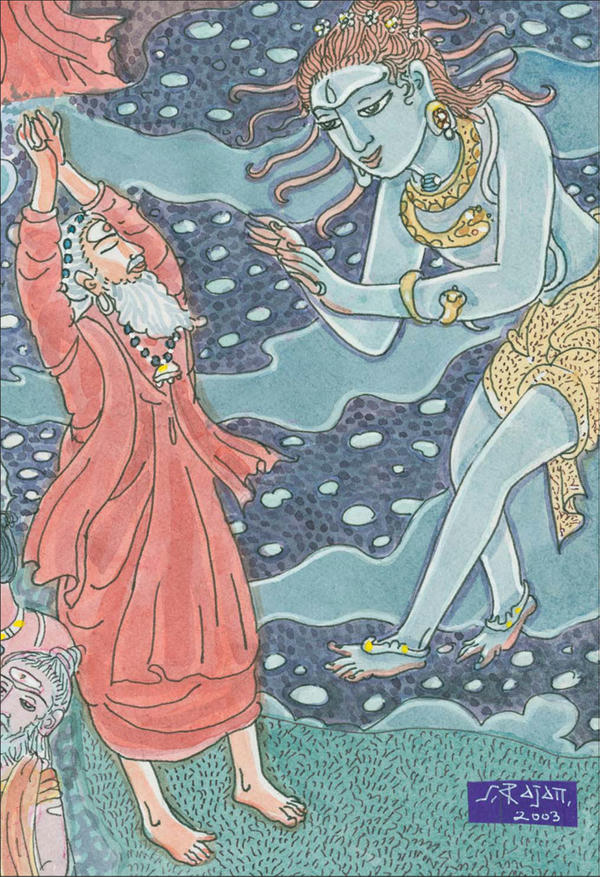

Gurudeva described God Siva as “the architect of the universe, with a beautiful human-like form which can actually be seen and has been seen by many mystics in visions.”

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •§

Kinship with a Vaishnava Order

In 1995, while traveling for three months in India with two of his swamis, Gurudeva was invited to give the major speech to 50,000 devotees in Mumbai at the 75th birthday celebration for Pramukh Swami Maharaj, the preceptor of the Bochasanwasi Akshar Purushottam Swaminarayan Sanstha (BAPS), a huge, Gujarat-based Vaishnava organization. §

The scene could have been right out of Vedic times, with dozens of orange-robed sadhus gathered around to catch a glimpse of the two gurus as they sat in mostly silent communion. Both taught a path that encompassed devotion and meditation, that insists on the strict and traditional rules of monastic life and that holds the guru essential to spiritual advancement. Both orders shared a distinctive mix of orthodoxy and progressiveness, of ancient ways and high technology, coupled with a guru-centric ethic where monks and householders work for a common goal. Gurudeva immediately sensed how profoundly these monks regarded their own guru by the loving reception they accorded him.§

Gurudeva wanted to see how the BAPS monks were trained, answer questions they might have for him, and most importantly, inspire and encourage them in their chosen path, which he so admired. So he was whisked to their sadhu training center in Sarangpur, several hours away. The village itself sits upon the flat plains amidst farm country. The center is a modern complex of two-story buildings that houses more than a hundred monks in training—each one an avid reader of HINDUISM TODAY. §

In the six-sided pavilion under a sprawling mango tree outside the publications facility, Gurudeva met with visitors, answered their questions and signed books.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •§

One of the BAPS monks asked, “Gurudeva, people call us fanatics. How should we respond?” Gurudeva turned the criticism around, “Take it as a compliment. They are only saying that because they are envious of your dedication and enthusiasm.” §

Later, Gurudeva told them to be faithful to their vows, not thinking of women, even in their dreams, and boldly offered advice that they knew in their hearts but, due to modern Indian sensitivities, they had never heard: “There is only one duty of the disciple. Obey your guru! Obey your guru! Obey your guru!” When he said this, the room erupted with the applause of 250 elated sadhus. §

After the meeting, each of the monks came forward to receive a handful of flowers from Gurudeva. It was a memorable visit, and uplifting for both monastic orders. Gurudeva later commented, “I have never seen such a training center for Hindu monks anywhere in the world.” §

Several years later, one of the BAPS senior monks was sent into the 2001 Gujarat earthquake disaster that killed 50,000 people. Pramukh Swami instructed him to direct the relief work for the people. “It seemed an impossible task, “ he told Rajiv Malik, who was writing a story on BAPS for HINDUISM TODAY, “like the story in the Upanishads of the disciple being sent to the forest with 400 sick cows and told to return only when the herd had reached 1,000. But I recalled Gurudeva’s words, ‘Obey your guru. Obey your guru. Obey your guru.’ and proceeded with confidence.” To this day, whenever BAPS monks meet monks from Kauai, they relate the story of Gurudeva’s powerful message and the transformative impact it had on their order, essentially giving them permission to be openly at the feet of their beloved guru.§

Gurudeva moved freely with monks of all sampradayas, feeling them to be his brothers in the great work of enlightening mankind. Every visit to an ashram or matha was an opportunity for encouragement. Sri Balagangadharanathaswami of Bangalore wrote: §

In many ways Gurudeva has been of great influence both on me as a person and to our institution. When he visited our educational institutions, he told me that education should not restrict itself to academics like a government program. He said we should teach our scriptures, our traditions and values as well. On his advice we have incorporated this, setting aside time for spiritual items. §

Sivaya Subramuniyaswami was pained to hear that female infanticide and abortions were being carried out in our hospitals, and he advised me that we should stop this practice. He was truly a messenger of peace. I was impressed by Sivaya Subramuniyaswami’s forthrightness. He would speak directly about issues relating to dharma and religion. I was deeply touched by his concern for society, especially issues concerning family and children.§

Visiting brother monks was often a time for adopting new ways of doing things. From one South Indian aadheenakarthar he got the style of his swamis’ earrings and the color of their robes, and from another an introduction to the Tirumantiram. In the wake of an earlier visit with the BAPS sadhus, he dove into their guiding principles, 212 couplets on how to live—strict principles that are followed by tens of thousands of families. Gurudeva drew on this body of work, called the Shikshapatri, when writing his own 365 Nandinatha Sutras. §

Spiritual Toolbox

Thousands of people came to Gurudeva for spiritual realization, hoping for some magic pill of enlightenment—and solutions to their problems in the bargain. They had grown up on stories of how the touch of a peacock feather had brought a total stranger to the path to Siva’s feet, and they hoped for a swift journey to the land of light for themselves. §

Gurudeva knew such happenings, while not impossible, were impossibly rare. As he grew older, he increasingly withheld the deeper practices, even prohibiting meditation at times, until devotees proved they were living a pure life, that they were worthy to practice yoga. He hoped to ensure that they would not be disappointed when success in meditation eluded them—as it ineluctably would, because of their impure lifestyle and unwholesome karma, their meat-eating, their lustful thoughts, bad habits, deep-seated resentments and unresolved hurts and fears. The strictness of his system of rules formed his first line of defense. §

Those not willing to adjust themselves were automatically kept away. To those who persisted, he offered not a magic mantra or a set of orange robes but tools for self-transformation that addressed the most basic levels of personal life, starting with learning to be a good person. He knew that spiritual attainment is hard work, and to achieve the summit of Self Realization requires more discipline, more commitment and training, more change in lifestyle and attitude than climbing Mount Everest requires. Only those with these qualities will succeed. Though not all understood this, he continued to press his shishyas on every front, his underlying hope being they would transform themselves inwardly and that transformation would usher in the spiritual illumination they sought but had no idea how to achieve. §

At no time in his ministry was he interested in creating a movement with thousands of followers. Always he preferred quality to quantity. He was so serious about only working with those who were willing to work on themselves that when devotees brought problems to him that clearly resulted from not following his advice or from neglecting their sadhana, he chided, “What am I to you, just a picture on the wall?”§

But no one, not even the most sincere and serious, came to him without at least some baggage, some blind spots and areas of their life that needed fixing. In his latter years, Gurudeva grew weary of fielding the same questions that he had heard for decades and giving the same advice—advice that was not always, even often, followed. The human condition was now an open book to him; he had heard it all—confessions of every transgression imaginable, every predicament and problem. The load of hearing all this and taking on the karma was heavy, requiring quiet moments each day to absorb it, lest it back up on him and disturb his nervous system. It was, he explained, his task to take them in and project them up through the top of his head and dissolve them in the inner light. §

He learned that it was more effective, and less troublesome, to put the work back on the devotee, to give a remedy, a penance, which he called prayashchitta. The goal and purpose was to unburden the subconscious mind of unresolved hurts and resentments, fears and repressions and the guilt of past transgressions. He gave a mystical explanation of penance:§

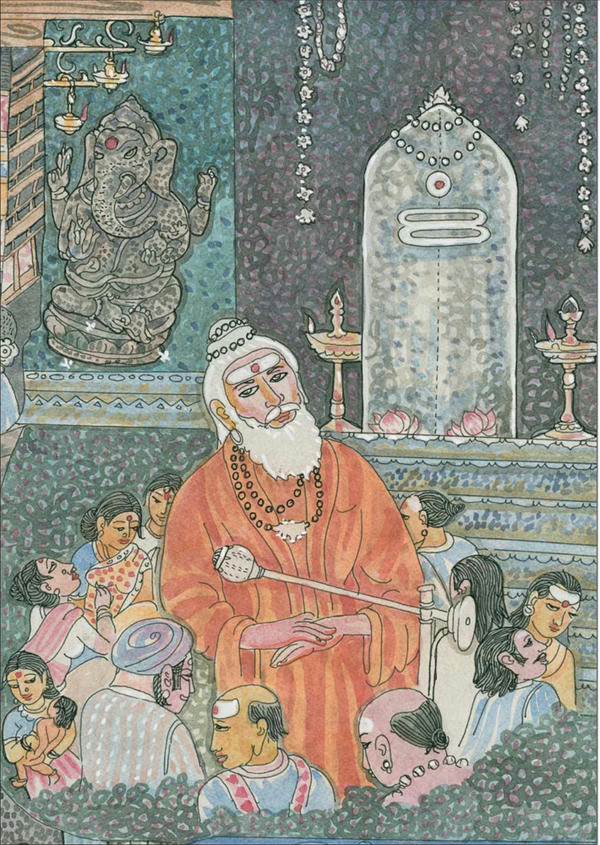

He had chosen Kauai for its remoteness, yet visitors discovered the monastery and came from all corners of the globe to be with the satguru, hear his talks and worship in Kadavul Temple with its giant murtis and crystal Sivalingam.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •§

The inner process of relieving unwanted karmic burdens occurs in this order: remorse and shame; confession (of which apology is one form); repentance; and finally reconciliation, which is making the situation right, so that good feelings abide all around. Therefore, each individual admission of a subconscious burden too heavy to carry must have its own reconciliation to clear the inner aura of negative samskaras and vasanas and replenish the inner bodies for the struggle the devotee will have to endure in unwinding from the coils of the lower, instinctive mind which block the intellect and obscure spiritual values. When no longer protected by its ignorance, the soul longs for release and cries out for solace. Prayashchitta, penance, is then the solution to dissolve the agony and bring shanti. §

There are many forms of penance, prayashchitta, such as 1,008 prostrations before Gods Ganesha, Murugan or Supreme God Siva, apologizing and showing shame for misdeeds; performing japa slowly 1,008 times on the holy rudraksha beads; giving of 108 handmade gifts to the temple; performing manual chores at the temple for 108 hours, such as cleaning, making garlands or arranging flowers; bringing offerings of cooked food; performing kavadi with miniature spears inserted in the flesh; making a pilgrimage by prostrating the body’s length again and again, or rolling around a temple. All these and more are major means of atonement after each individual confession has been made. §

Devotees were amazed at Gurudeva’s ability to translate abstract philosophical principles into simple language—then go one step further to conceive specific sadhanas designed to put those principles into practice. The mystical axiom of “clearing the subconscious,” so essential in yoga, provides an example.§

The subconscious mind is the storehouse for the conscious mind. All the happenings of each day and all reactions are stored up there. When the subconscious is in control, the control is at one rate of vibration. When the subsuperconscious is in control, after the subconscious has become understood, concentrated and cleared of all confusion, the vibratory rate is higher.§

It is one thing to know there are unresolved memories, feelings and experiences that need to be released; it is another to have a means to accomplish this. Faced with so many devotees needing release from the past, he evolved, through meditation, a simple but profoundly effective technique that anyone could use. Most did, and it proved crucial for their spiritual progress. Gurudeva called it vasana daha tantra, “purification of the subconscious by fire.” §

He instructed devotees to take their conflicts and pains, their confusions and negative experiences and write them down, bring them from the deep subconscious into the conscious mind, and intentionally, consciously, burn them up, both physically as the paper turns to flames and ash, and psychically, through seeing the physical representation of the problem being incinerated. §

Mental impressions can be either positive or negative. In this practice, we burn confessions, or even long letters to loved ones or acquaintances, describing pains, expressing confusions and registering grievances and long-felt hurts. Writing down problems and burning them in any ordinary fire brings them from the subconscious into the external mind, releasing the suppressed emotion as the fire consumes the paper.§

He counseled those practicing this tantra to burn their problems in a common fire, making sure they distinguished between a sacred fire pit into which prayers are offered and an everyday fireplace or cauldron where trash is burned. The process was so effective that Gurudeva developed a system for methodically going back through one’s entire life in this way. §

The Forgotten Foundation of Yoga

Nearly one third of Gurudeva’s third book of the trilogy addressed the ancient yamas and niyamas, which he called the Cardinal Virtues of Hinduism. He pointed out that these twenty restraints and observances are a necessary foundation for the practice of yoga. Without them, no spiritual pursuit would bear lasting results. §

Dr. S.P. Sabharathnam Sivachariyar, a Saiva Agama scholar, observed that this was just one example in which Gurudeva had, like a true rishi, brought forth the wisdom of the Agama texts without having ever read or known of them. After reading Gurudeva’s explication of the yamas and niyamas, Sabharathnam commented, “The observation that spontaneously dawned in my heart was: Here has come the true acharya who could shape well the modern community, who could perfectly guide humanity, being tuned to the true spirit of guruhood.” §

He noted an uncanny similarity in Gurudeva’s words to those of a verse from the Sukshma Agama, which reads: “The system of yoga in which yamas and niyamas are not practiced is as fragile as the mansion without foundation, as vain as the flower without fragrance and as imperfect as the knowledge not centered on the oneness of Siva and soul.” Sabharathnam also observed:§

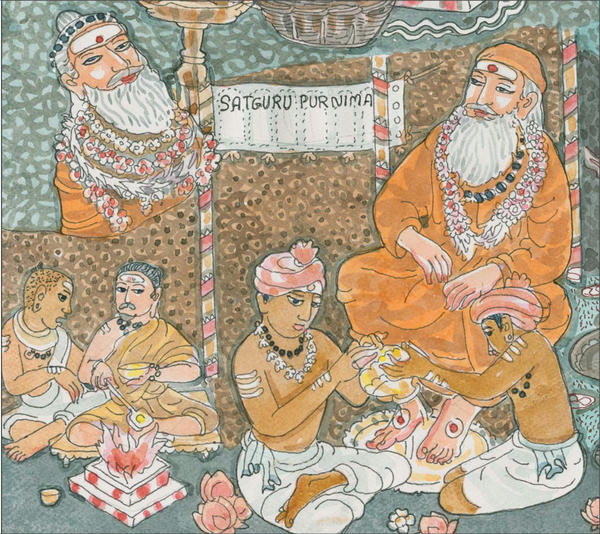

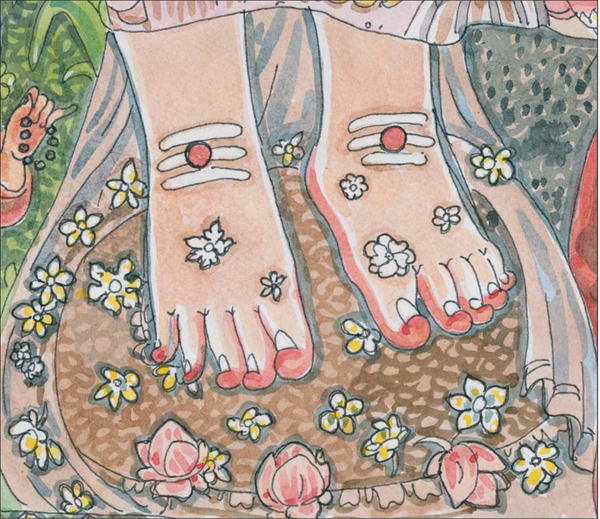

On every full-moon day in July, the monastery celebrates Satguru Purnima, worshiping the guru’s feet at the site of the Svayambhu Lingam. In worshiping one’s own guru, all preceptors are honored.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •§

Gurudeva’s explanations on the real nature of the shaktis of Mahadevas living in the inner Third World, on the invincible vel of Skanda, on the five states of mind, on the nature of the twenty-one chakras—seven in the upper realm, seven in the middle realm and seven in the lower realm—on the significance of temple, temple rituals and mantras, on the role and significance of colors and such other elucidations are the undistorted and clear reflections of the verses of the Saiva Agamas.§

Gurudeva was the first yogi I know of who dealt with the chakras lying below the muladhara, which have been mentioned in the yoga section of the Sukshma Agama only. §

The crowning revelation is Gurudeva’s Shum language of meditation. In the Sukshma Agama, Lord Sadasiva reveals the finest and highly transcendental disciplines of Sivayoga to the much advanced Sivayogis. At one point He stops the instructions and says: “Enough with these directions. There are many more subtle and transcendental aspects of this sarvatma-nada yoga. These will be revealed to the competent Mahayogis in due course of time. Not now.” I was reminded of these lines when I came to know that the Shum language of meditation was unfolded to Gurudeva at Ascona, Switzerland, in 1968.§

“Stop Abusing the Children”

In the late 1990s, Gurudeva learned that many of his devotees, even long-time shishyas, were using corporal punishment on their children. Shocked and hurt by this revelation, he demanded an abrupt change. No more hitting, pinching, ear-twisting, slapping, beating or pummeling; no more verbal abuse, humiliation and use of shame and blame. §

To help parents compensate for past misbehavior, he required them to perform penance. First, they had to sincerely apologize to their children and perform specific practices, such as standing in front of a mirror while slapping themselves five times for every time they slapped a child. Second, he instructed them to hold classes in Positive Discipline in their community. Positive Discipline is a system developed by California educator Dr. Jane Nelsen, and presented in a series of books and lectures showing how to raise children with encouragement, love and respect rather than blame, shame and pain. §

Manon Mardemootoo, a long-standing devotee of Gurudeva and a prominent attorney, was among many on the island of Mauritius who wholeheartedly undertook this mission. He said, “To take these teachings of ahimsa into the public and make them a living reality is the present sadhana of Gurudeva’s devotees here in Mauritius.” Thus, in 1998 Gurudeva began an ardent campaign for the right of children to not be beaten by their parents or their teachers, and helping parents raise children with love through Positive Discipline classes taught by his family devotees as their primary community service. A devotee in Singapore explained:§

Gurudeva advocated abolishing corporal punishment in homes and schools, directing his devotees to teach classes for other Hindu parents in nonviolent means of parenting and to change school policies regarding corporal punishment of students.§

In the last few years, Gurudeva’s devotees have waged a campaign against corporal punishment in Singapore’s homes and schools. They made substantial progress in the local schools, which were already tackling the issue, by seeing to it that teachers still using corporal punishment were reprimanded and retrained in better methods.§

Always Now

Aside from what Gurudeva did, how he helped others and who he was known to be, there was something intangibly magical about him. Because he lived at the center of himself, the Self of all, everyone felt close to him and loved him dearly. For them, his life was like a magnificent rainbow, arched high above the woes of the daily norm. Gurudeva emanated a sense of being ever youthful, unencumbered, innocent, open and always in the now. §

To have the feeling of being in one place, and that everything is happening around you, like a maypole—this is how I feel these days. I watch the cycles of life as they flow one into another. The physical-plane cycles flow into the astral-plane cycles which flow into the superconscious-plane cycles and back to the physical-plane cycles again as men and women unfold on the path. This state is what I call “doing nothing.” Just watching, watching, watching.§

He was, despite the most serious challenge or calamity, ever poised, centered, detached. Whatever he was doing–discovering Shum at Casa Eranos, laying the first stone of Iraivan Temple–he maintained an effulgent joy that knew no suppression, a boundless love that made everyone around him feel he regarded them as special. §

He imbued his monastics with this magical quality as well. Coupled with the unfoldment of their decades of brahmacharya, it gave them an abiding joy that made visitors remark, “Everyone here seems so happy!” It was true. Happy, inspired and driven to perform sadhana and to serve—these were irrepressible qualities that lived on in his order even after he left his Earthly frame. §

The Kularnava Tantra proclaims, “At the root of meditation is the form of the guru. At the root of puja are the feet of the guru. At the root of mantra is the word of the guru, and at the root of all liberation is the grace of the guru.”

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •§

He had an uncanny power to attract and continually train and intrigue—with his mystic, otherworldly insights into the nature of reality—a strong group of monks and family people around him. He trained these dedicated souls carefully, cultivating the abilities of each so he could delegate increasing responsibility to them. This enabled him to accomplish what no single person could have done in one lifetime. Though some of his devotees—monks as well as lay members—found their personal karmas would not allow them to follow where he led, the rest worked unceasingly to fulfill the mission that he, and they, were born to carry forth. In earlier years, he coined the term soldiers of the within to name those who had gathered around him for this inner work. “Born for the job,” he often commented.§

It was, no doubt, Gurudeva’s keen centeredness that made all his efforts so successful. He approached every project and responded to each need and problem with acute attentiveness, daily assessing his strategy, consulting with his senior monks, and at each day’s end summing up the progress and noting areas of concern. He was capable of a kind of detachment seen in a good general on the battlefield who sees soldiers fall, yet, while it is painful, keeps the strategic overview and does not get caught up in the immediate tragic loss. Gurudeva could do that: keep a remarkable detachment from events of the day, always seeing a larger field of view, a longer immediacy.§

“Is This Legal?”

In the mid 1990s, the popular mind started to embrace the World Wide Web. The monks were monitoring the beginnings of this amazing phenomenon, little knowing that the web would change the way the monastery, and the world, would work. It was new, exciting, confusing and not a bit user-friendly. Still, the monks began to cobble together incipient uses, and showed them to Gurudeva. Soon his basic publications were online for all to read, and unlike any other distribution system in history, it seemed to be free. §

One morning the monks connected his computer to the Internet with a dial-up modem. After surfing around the web for a while, he turned to ask seriously, “So, who pays for all this? Is it legal?” Turns out, it was legal, though no one present could quite explain how. Within months the Internet became a major place to publish his many works: HINDUISM TODAY, Dancing with Siva, a page of Aum graphics and more. §

As the monks’ skills matured, Gurudeva was generous in sharing their expertise with others, such as designing a website for the Hopi Indians to help them archive and preserve their tradition. Even the office of Kauai’s mayor turned to the monastery for help with this new media.§

One day in the summer of 1998, he gathered his nerd herd in the Cedar Room, a conference room in the publications center, and asked if it would be possible to share with the world the daily happenings at the monastery, thus bringing his global spiritual fellowship together each day, digitally. From that request grew “Today at Kauai Aadheenam,” or TAKA, a mix of news, audio talks, photos, spiritual quotes and tidbits about his mission at the monastery and members’ activities around the globe—perhaps the world’s first blog. §

Almost daily for three years, he addressed pilgrims and seekers on the web, speaking on dharmic subjects or answering their spiritual inquiries. He coined the word CyberCadets, his name for visitors to the website, and invited them to send in questions by email. His answers were recorded and posted to TAKA, usually the same day they were spoken; these may have been the world’s first podcasts. Hundreds of these CyberTalks accrued, and for the first time in history anyone with a computer and an Internet connection could hear the satguru speak to real people about real life issues in near real time, for free. §

There was a small downside to TAKA, Gurudeva discovered. When traveling, his common pattern for decades had been to share with devotees in each city his experiences over the past few days. Arriving in Malaysia, he would give a news update of his stay last week in India and Mauritius. Now, in 1999, he found everyone in these audiences looking distracted, almost disinterested. He asked why, only to be told, “Gurudeva, we saw all that on TAKA yesterday.” That moment he realized that TAKA had truly tied his shishyas together, and it was his cue to find new subjects to talk about during his travels. §

The Internet would continue to evolve, and the monastery website would become one of the leading Internet repositories in the Hindu world. Gurudeva would see this when searching for some Hindu custom or fact only to have the search engine of the day deliver links to his own writings. Even years later, the monks would marvel at how their resources were consistently near the top of Google search results for “Hinduism.”§

The 1995 Journey to India

From December 1995 to February 1996, Gurudeva traveled through six nations and throughout India, where he was greeted with overwhelming affection in every town. Many of his initiatives were advanced during this journey, but it proved a major turning point in another way. Late one afternoon toward the end of the journey, something unexpected happened on a flight from the South to the West.§

A crowd of 5,000 was waiting in Ujjain, an historic Saiva Siddhanta center. Elephants stood ready at the airport to lead the world-famous satguru from Hawaii to the sacred centers of the city, including the famed Siva temple, Mahakaleshwar. But on the Mumbai-bound plane, Gurudeva experienced a seizure, falling unconscious in his seat for some two minutes. Stewardesses leapt to his aid and a doctor seated just in front provided some counsel, taking his pulse and shrugging off the episode as a non-event. Gurudeva was unfazed and insisted on continuing with the arduous itinerary, giving a major speech in Ujjain the next day and then traveling on to Malaysia and Singapore. §

There were more seizures in the days ahead. The two swamis with him were terrified by the powerful convulsions, even fearful for his life, but his own experience was simply of waking from a sleep, and he would inevitably ask, “Did you smell that sweet fragrance? How long was I out?” Learning that it was a minute or more, he still insisted that the journey continue. The episodes continued on occasion until his passing in 2001, though they grew milder in later years. §

Back on Kauai, his doctors insisted on an MRI, anxious to discover the underlying cause of the seizures. “No, never,” was Gurudeva’s firm response when the monks broached the idea, “I don’t want to get under the thumb of the doctors. They will fill you with fear, take control of your life, drive you into bankruptcy. It never ends once it begins. That’s no way to live.” No tests were allowed.§

Fully aware of the gravity of the matter, Gurudeva took days to meditate on the course of action he would take. One day he shared with a few monks that he would be observing a three-year sabbatical, staying on Kauai and not traveling. It was a radical shift from the rigorous schedule of dynamic journeys he had been on. Days later he announced to all the monks his resolve to take a self-imposed retreat on Kauai in order to work on his legacy to the world, The Master Course trilogy, consisting of 1,000-page editions of Dancing with Siva, Living with Siva and Merging with Siva. It was a brilliant example of how he could take the energy of any situation and transform it into something positive, utilize a setback to create something extraordinary that never would have otherwise existed. §