Chapter Twenty-Five

Building a Saiva Stronghold

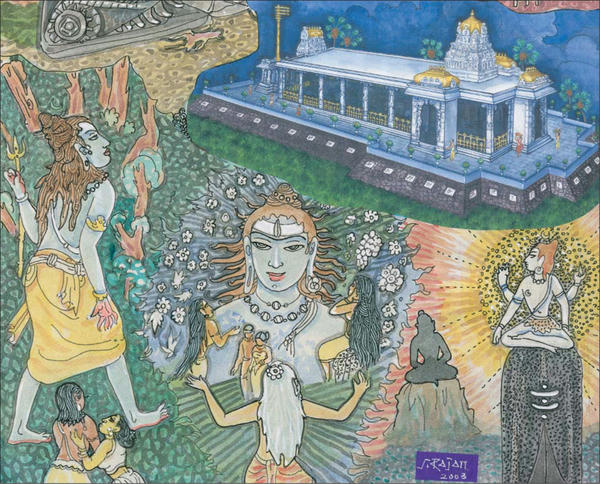

The power of the Kadavul Siva Temple became supreme following the installation of the Lord Nataraja Deity in 1973. The name Kadavul, from Tamil, is among the oldest names of Lord Siva, literally meaning “He who is immanent and transcendent” or “He who is within and without.” Humble in its physicality, the temple had a life-transforming shakti from the start, the natural convergence of Master’s vision, Siva’s presence and Murugan’s yogic thrust. It was, Master said, a fire temple, for fire is the element of change, of reformation and even annihilation. Some people entered the temple and began to weep uncontrollably. They would come in one state and leave in another, their lives changed in large and small ways. So potent its energies became that Master would in later years, just for a time, allow only vegetarians to enter, seeing that others were too overwhelmed by the energy, overcome by the transformative tsunami of shakti. §

On Kauai island—which, he loved to quip, “is surrounded completely by water”—Master established Kadavul Temple, shipping in six-foot-tall granite murtis of Ganesha and Murugan, a bronze Nataraja, a 16-ton Nandi and the world’s largest crystal Sivalingam.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •§

The monks found themselves awash in this new energy. Many were thrown into a turbulent time of discipline, change, inner purification and tapas, their tears watery testaments of the trials the guru set for them. This intensity launched a difficult time for the entire Order, a time of transition and of affirming commitments to their vows as Saivite monastics. It was a time of adjustment, as well, to the directions provided by the Shastras and to Master Subramuniya’s stern demands, his uncompromising expectations of their ideal life, their most perfect dharma. “No one said monastic life would be easy,” he would console.§

He created a Flow Book which defined, in minute detail, how a Saivite monk should live, respond, learn, converse, cook, clean, perform chores, take direction, dress, eat, sleep, meditate, worship, surrender, get along with others. Each entry was signed in his own hand, to authenticate his acceptance. Every facet of life was described in the Flow Book, and the satguru’s every guideline, called a flow, was to be followed—always and without exception, ever and without excuse.§

The searing shakti of Kadavul Temple, the satguru’s renewed call for the elimination of habits and attitudes unbecoming of a Saivite monastic and the new requirement that all members of the Order be full, formal, proud Hindus all conspired to cause unprecedented uncertainties among the monks. Master made it plain that a total severance of all previous religious ties was necessary. This was to be an order of purely Saivite renunciates. It was an extraordinarily brave and demanding requirement. §

Some may have come to be with a kind of Eastern messiah. Some may have thought themselves universalists beyond the pale of religion, any religion. Others may have simply discovered the limits of their will to change. Whatever the causes, many left. One and then another. Two and then three more, again and again—back to their families, back to their personal karmas, back to who they were before they entered the monastic path. It began first with the monks and then the members being asked, “What religion are you?” and “What religion do you think Master is teaching?” This was a time of great upheaval, with half the monastic order leaving, and a similar percentage of lay members. §

From a worldly point of view, the departures were catastrophic, like a devastating tornado sweeping through a neighborhood and blowing half the infrastructure to the horizon. All that training, all that dedication, gone. So what was Master’s reaction to it? He rejoiced. He thanked Siva for sending all these men away, men who, with their doubts, would have brought the Order harsher karmas in the years ahead. With that prospect gone, he called for a party! §

On February 15, 1975, Master had a three-part vision of God Siva which would culminate in the founding of his Iraivan Siva Temple. In it he saw Siva walking in a valley with devotees, then he saw Siva’s face close up, then seated on a svayambhu Sivalingam.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •§

America’s First Aadheenam

In the early hours of February 15, 1975, lying on a tatami mat in his Ryokan room, Master was having one of those profound sleeps that is neither awake nor full of dreams. In that clear space above physical consciousness, the 48-year-old satguru experienced a threefold vision that would be the spiritual birth of the great Siva citadel called Iraivan Temple and its surrounding San Marga Sanctuary.§

I saw Lord Siva walking in the meadow near the Wailua River. His face was looking into mine. Then He was seated upon a great stone. I was seated on His left side. This was the vision. It became more vivid as the years passed. Upon reentering Earthly consciousness, I felt certain that the great stone was somewhere on our monastery land and set about to find it.§

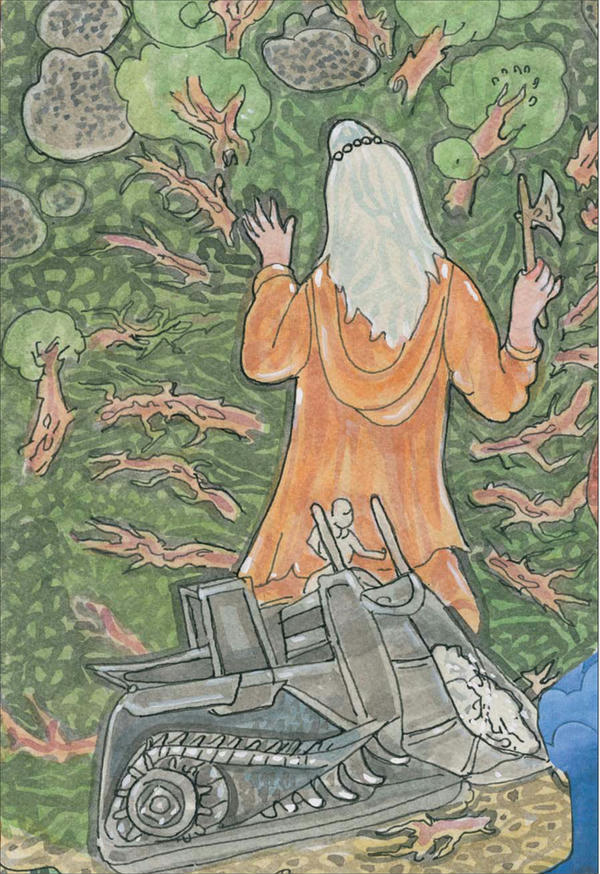

Guided from within by my satguru, I hired a bulldozer and instructed the driver to follow me as I walked to the north edge of the property that was then a tangle of buffalo grass and wild guava. I hacked my way through the jungle southward as the bulldozer cut a path behind me. After almost half a mile, I sat down to rest near a small tree. Though there was no wind, suddenly the tree’s leaves shimmered as if in the excitement of communication. I said to the tree, “What is your message?” In reply, my attention was directed to a spot just to the right of where I was sitting.§

When I pulled back the tall grass, there was a large rock—the self-created Lingam on which Lord Siva had sat. A stunningly potent vibration was felt. The bulldozer’s trail now led exactly to the sacred stone, surrounded by five smaller boulders. San Marga, the “straight or pure path” to God, had been created. An inner voice proclaimed, “This is the place where the world will come to pray.” San Marga symbolizes each soul’s journey to liberation through union with God.§

That vision must have wrought profound changes in Master’s interior world, for it certainly was the seed of profound changes on the outside. Immediately he embarked on a long journey that would bring Saivism deeply into the lives of his followers and build not only a temple to honor his life-changing vision, but a traditional aadheenam like the great ones he had visited in South India just three years before. §

Master had observed there was no such temple/monastery complex in all of the West for Hindus and threw himself into its creation. With no authorities to guide, he searched within for the systems of spiritual and material management and crafted an astonishing set of procedures and flows to guide every aspect of his several institutions, and to inform the monks’ lives and relationships. At this point Master changed the name of his headquarters from Sivashram to Kauai Aadheenam, which, for the sake of local islanders, he also called Kauai’s Hindu Monastery.§

His travels diminished as he began to set roots deep in the Kauai soil. Under his instructions, the senior monks began a thorough study of Saiva Siddhanta and its relationship with and difference from Adi Shankara’s Advaita Vedanta. Rishi Tirumular’s Tirumantiram and Saint Tiruvalluvar’s Tirukural, the seminal spiritual texts of Saiva Siddhanta, were translated, memorized and commented upon in his inspired talks. He commissioned the carving of life-sized granite murtis of Tirumular and Tiruvalluvar in South India and brought them to the monastery, giving visual form to their psychic and theological presence. §

Late in the 1970s Master had two magnificent, six-foot-tall murtis, the portly Ganesha and the noble Murugan atop His peacock, carved by renowned master architect Nilamegam Sthapati in Mahabalipuram. In February, 1979, they arrived from India, and Master had them installed in Kadavul Hindu Temple on June 1. On a remote American island, Saivite Hinduism was being fully grounded in the West, every aspect of it—not a modern American version of Hinduism, thought by some to be a logical, even inevitable, evolution, but the complete, unabridged Hinduism that has been followed for millennia. §

A 32,000-pound black stone Nandi was also brought to Kauai to sit outside Kadavul Temple in perpetual adoration of Lord Siva, making TV’s Channel Nine news, which opened the piece with the tongue-in-cheek headline “16 Tons of Bull.” The enormous sculpture, ordered in 1976, took four years for Nilamegam Sthapati to complete, arriving finally on August 16, 1980. He confided to the monks that Nandi, the “joyous one,” ranked among the finest creations of his lifetime. The huge granite bull—six feet tall, nine feet long and five feet wide—was the largest carved in India in the 20th century and among the five largest ever carved. §

Convinced he could find the Sivalingam that had appeared in his vision, Master hired a bulldozer, instructing the driver to follow him into the dense undergrowth, carving a trail through the trees that would become the San Marga path.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •§

For the next decade Kadavul Temple pulsated with a palpable shakti that sustained the monastery and changed the lives of all who visited. With the basic elements of the temple in place, Master allowed no further construction until the fall of 1984. Then he marshalled a major construction effort reminiscent of the early 70s, landscaping around the temple, putting in hundreds of feet of concrete paths, lining Kadavul’s bare concrete block walls with lava rock inside and out, tiling walls, floors and ceiling and installing shelves for the 108 bronze tandava murtis, depicting Siva in 108 dance poses, that he had specially cast in South India. §

March of 1985 marked the traditional twelve-year point in the life of Hindu temples when refurbishing and repairs are permitted, prior to a grand reconsecration ritual. You might call it a full restarting of the system, in which the energy is actually removed from the temple during extensive homas, and then placed back inside once physical improvements are complete. Master tried it out, this one time. §

Two priests, one from Madurai and another from Bangalore, performed elaborate rites that took the power of the temple Deities into special kumbhas, which were then transferred to a temporary yagasala constructed under a nearby banyan tree. §

The effect of the three-day ceremony was not subtle; it was as if the Earth had slipped off its axis. The feeling was eerie, unsettled, downright spooky. The temple, emptied of is spiritual potency, felt like an abandoned warehouse, a feeling Master and the monks did not enjoy. The weather went wild with horizonal rains, thunder, lightning and howling winds. The monastery was upset as never before. Master vowed to never do this again, even though it is traditionally required every twelve years. It took months until the sannidhya was restored. §

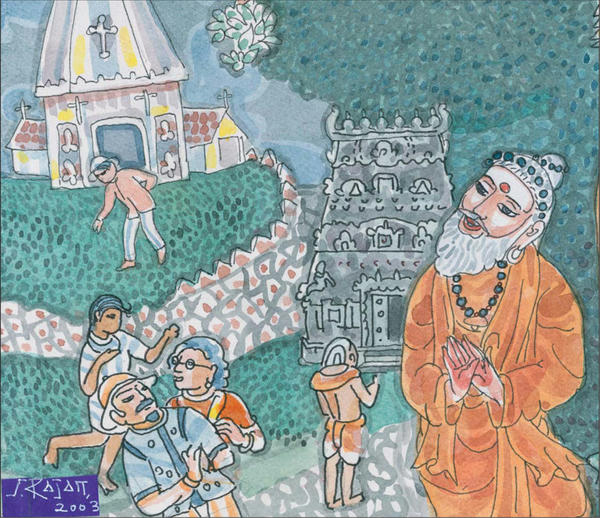

If a Christian asked to be his devotee, Master would send that person back to his church elders for their blessings and a formal release. Stealing from religious flocks was such an anathema to him that he created an ethical form of conversion.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •§

Building a Yoga Order

Naming each year had long been Master’s way of setting a direction for everyone. He called 1974 “The Year of the Guru” and 1975 “The Year of the Monastics,” his way of informing one and all that all would be working on the guru-shishya relationship. Training and more training. The monks did everything themselves, as was once done in India, where today much of a matha’s care is given into the hands of overseers, cooks, groundskeepers, carpenters and accountants. Not at Kauai Aadheenam. Virtually every task was done by the monks, who took great joy in the ideals of self-sufficiency and the diverse skill set that emerged. It was hard work. §

The monks were challenged and corrected, not always softly, and were expected to respond, expected to receive the correction in a nondefensive spirit and use it to change and improve their lives. Those who threw it back, who cried, “Unfair,” soon learned that such tactics did not work. Obey the guru; that worked. Eschew self-defense and stop blaming the blamer; that worked. Change yourself and don’t demand others to do the same; that worked, too. §

Years later Master would smile while explaining that the monks were all soft and gentle, harmonious and kindly, and that they had gotten that way in much the same manner a jeweler polishes gems. Rough gems are thrown into a turning vat and allowed to tumble for days against one another, each being an agent of abrasion for all the others, each losing its own sharp edges by constant collisions. In such a way, the monks—living together, working together, struggling and learning together, meditating and worshiping together under the guru’s direction—each slowly became a polished gem. Differently faceted, of different colors, but all gems. All due, they knew, to the guru’s grace.§

These years of working with the monks led Master to stress the artisan-apprentice system of training. Older monks, with their accumulated skills, were assigned to train the younger ones, and the younger to serve and learn under their elders. In time, this evolved into what Master called the kulam system, the overall architecture of monastery management of duties and responsibilities. Kulam means “family” in the Tamil language and, by extension, describes a group of monks in the same field of expertise and service. Five kulams emerged, each called by one of Lord Ganesha’s names, each an independent team responsible for an aspect of the monastery’s daily routine: temple/kitchen (Lambodara); members’ nurturing/teaching (Ekadanta); administration/finance (Pillaiyar); buildings/grounds (Siddhidatta); and publications (Ganapati). §

The monks were sent to India and Sri Lanka for longer periods during this time, to absorb, learn, immerse themselves in Saivism and in the worship of God Siva at His great temples. Master had them work on the scriptures, learn Siva puja from the Sivacharyas, experience the magic that is India—and the culture, which he regarded as the world’s most sublime. With the monks well established in the faith, he made another major move. §

The Conversion Conundrum

“I have paid my debt to my countrymen. Henceforth, I live in service to Tamil Saivites throughout the world.” With these words, spoken to all assembled in the San Francisco Temple on January 5, 1977 (his 50th jayanti), Master Subramuniya formally and finally retired from public ministry in the West. He knew from experience that commitment to a single spiritual path is essential to the deepest goals of life, and those who waffled or straddled or hedged would not get far. So, he determined not to be guru to the curious and the uncommitted, choosing to dedicate the remainder of his lifetime in service to the Saivite religion and the greater glory of God Siva, the Gods and his satguru, Siva Yogaswami. No more public lectures. No more explaining for the umpteenth time what yoga means. §

Again, some of the monks, even some who had been close for decades, left the Order, unable to follow where Master was leading. Though initially it was one of his rare disappointments, this winnowing process proved part of a larger plan. Those who stayed were whole-heartedly dedicated to fulfilling Master’s mission. This created a harmony and one-pointedness that could not previously have been achieved, or even imagined. The lesson was not lost on the monks: the strength of an organization depends on its members’ level of commitment; in more general terms, quality is more important than quantity.§

For the last two decades Master had taught the highest truths of advaita, the Self God, to students with non-Hindu backgrounds. The real-world trials and tribulations through the years had convinced him that in order to have these lofty teachings bear fruit in his students, they must fully embrace the Hindu religion and culture, eschewing all others. He saw the power of one-minded commitment to a path, and the infinite distractions that face anyone who has not the strength of such focus. The loftiest of human spiritual summits was only for the strong and the sure-footed.§

For years Master had seen the effects of divided loyalties, those who kept their Christian names and a few beliefs while adopting a Hindu lifestyle and nickname. It did not work; it divided the person, evoking a religious schizophrenia. One should decide who one is, fully and forever, as he had done. Never mind what family or community might think. §

Thus, in 1977, he intensified requirements for his Western devotees to sever all prior religious, philosophical loyalties, legalize their Hindu names and formally enter Hinduism through the name-giving rite, upholding the same standard that he required of his monks. To exemplify the ideal he was asking of them, he dropped the name Master and adopted a traditional Hindu name for a spiritual preceptor: Gurudeva. §

This all went against the grain of many in the Hindu world, who cringed at the word conversion. But he explained that conversion is nothing new for Hinduism. The advent of Jainism and Buddhism in India in 600 bce resulted in the conversion of millions of Hindus. Centuries later, revivals resulted in the reconversion of millions of Jains and Buddhists. In modern times, conversion to or from Hinduism remains a major issue, often resulting in extreme disharmony within families and towns. We have Hindus switching as a result of enticement or deception. We have Indians who converted wanting to return to Hinduism. And we have non-Hindus from lands outside India requesting formal entrance into the faith, including those who have married a Hindu.§

Gurudeva addressed each of these issues, ultimately formalizing his experience and suggestions for “ethical conversion” in the book How to Become a Hindu. Most conversions in religion, he observed, are forced or wrongly motivated. Catholics stealing from the Jewish flock, Muslims converting from among the Baptists, Mormons and Pentecostals harvesting souls—that awful phrase—aggressively from them all. Gurudeva thought religions should respect each other. If, say, a Jewish boy wanted to convert, he should be encouraged by his new spiritual advisors to seek the blessings of his rabbi, not run away from the synagogue in the dark of night.§

As with his approach to most topics, he started with a mystical insight. In ancient times, people tended to reincarnate right within the same village and religion time and again. “Now,” he said, “with modern-day travel and worldwide communication, this tightly knit pattern of reincarnation is dispersed, and souls find new bodies in different countries, families and religions which, in some cases, are foreign to them.”§

For such a person, the “Eastern soul in a Western body,” he proposed a thoughtful and peaceful method of self-conversion. He required his devotees wanting to convert from a previous faith to study that faith and explain convincingly, point by point, why they no longer held its beliefs. He sent them back to their churches, synagogues, even previous Hindu gurus, to attend services for a while and speak with their ministers. Every chance was given for them to change their mind, or to have someone change it for them. §

If they passed this test, they were required to demonstrate their knowledge of Hinduism through a series of exams, legalize their new Hindu first and last name, then enter the faith formally through the name-giving rite, namakarana samskara, in an established temple. The name was important to Gurudeva, and he insisted his shishyas put their legal name on all documents—passport, driver’s license, bank accounts, everything—a requirement for Church membership to this day. Seeing the tendency of many groups to keep the birth name and informally adopt a Saivite Hindu name, and the dual identities provoked by toggling between the two, he insisted on a single, formal, legal Saivite name, and would settle for nothing less. In early years he had long-time members help newcomers make this transition, but eventually he required those interested in his teachings to do it all on their own strength and motivation. §

There were many among his devotees who had no previous religion, even though they grew up in the West. These seekers were allowed to adopt Hinduism as their first religion, through the study of it and the name-giving ceremony, without the need to convert. Gurudeva strongly enjoined Hindus of the broader community to welcome sincere Western converts and adoptives into their midst and not shun or ignore them, as is often done. §

The great debate of the 80s centered around the two schools of Saiva Siddhanta. Gurudeva’s own realizations were in consonance with Saint Tirumular, who spoke of the nondual union of Siva and the soul, while many Saivites took the side of Saint Meykandar, whose pluralistic teachings decreed an eternal separateness of God and soul.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •§

Those who undertook this serious conversion to Hinduism went through a great fire which transformed them forever, hardened their commitments, purified their loyalties and made them some of the strongest Hindus in the world. This strictness was radically different from the stance of all other Hindu and quasi-Hindu groups, most of which required little or nothing by way of real change or commitment. Gurudeva would jest that they abhorred “the C word,” that today’s seekers are deeply committed to remaining uncommitted. This would set his followers apart and make them leaders. Years later, Hindu philosopher and writer Ram Swarup, who met Gurudeva and his shishyas and contributed articles to HINDUISM TODAY, wrote of them in The Observer, New Delhi, 1998:§

They are not NRIs. They are mainly white Americans—converts, Hindus by choice, and some are sannyasins at that. Those of us Hindu by birth tend to take Hinduism for granted and neglect its deeper, spiritual categories. But it is different with those who embrace it after much reflection and self-searching. They are seekers and sadhakas; they are interested in the problems of God, of Self, of inner life, of dharma and mukti.§

The year 1979 began with a whirlwind week of Guru Jayanti celebrations that included over twenty namakarana samskaras conducted in Kadavul Hindu Temple. Devotees receiving this name-giving sacrament, marking their entrance into the Saivite Hindu religion, had studied for several years with Himalayan Academy. Many had completed arduous severance procedures from their former religions. It was a landmark event in American history. §

In the coming years, after hundreds of self-conversions and namakarana samskaras, Gurudeva became content with his fellowship, proud of its strict adherence to dharma. Thereafter, he only reluctantly took others into the faith—and only if they knocked the door down with their urgent sincerity. He had crafted a Hindu community in the West, built it from scratch, and spent the rest of his life from within the confines of Hinduism with little connection to the merely curious, giving his energies to those who had made a full commitment to the Hindu dharma. §

The vision of the future was clear in Gurudeva’s mind. In it, Saivite Hinduism held a place of honor alongside the other faiths. Hindu families in the West were strong and integrated, supportive of one another and firm in their spiritual commitments. Working toward that future, he assembled all of the elements, one by one, giving large tasks to his monks. §

Under his direction, they developed family codes of conduct and discipline, ministerial guidelines, children’s study courses, Hindu hymnals and rites of passage to guide Hindus from conception to death. He crafted certificates to qualify lay chaplains and school teachers, developed a Saivite homeschooling program and wrote lessons to guide teens through their difficult years. The Hindu Businessmen’s Association was created to bring stability to Hindu entrepreneurs and the Hindu Women’s Liberation Council to give a forum to women. §

His vision encompassed the East as well, for he saw a lack of training there, too, especially for children. In Alaveddy, Sri Lanka, his Subramuniya Ashram initiated a highly successful series of classes in spoken English for children, along with classes in music, dance, art, Tirumantiram and Devaram hymns.§

He propounded the need for national and even international councils of Hindu organizations to aid in forwarding and sharing the knowledge of experience and experiment among the thousands of Hindu congregations that he saw would one day dot the landscape of the United States, Canada, Britain, South Africa, Europe and Asia. While no such communities existed at the time, his vision would manifest in a mere thirty years. To tie far-flung groups together, Gurudeva worked hard to reestablish the monastic printing facilities, bringing equipment from Nevada to Kauai and founding a newspaper, The New Saivite World, which gave news of Saivism around the world. §

In doing this work, Gurudeva had precious little help. Those who knew the tradition were on the other side of a non-Interneted world and not much able to guide. This drove him within, to seek the guidance of Yogaswami; and in dozens of crucial moments, that guidance flooded forth. Gurudeva would frequently tell the monks that Yogaswami visited in a vision or meditation, gave bold instructions to do this, to avoid that, to initiate a project or let another go. Yogaswami was his connection to the true Saiva path, and Gurudeva assiduously followed every hint, however subtle, that came from his guru. §

One day, Gurudeva reported, Yogaswami gave a three-word order with no explanation: “Don’t be equivocal!” Gurudeva asked the monks, “What does equivocal mean?” Hearing that it means to be uncertain and full of ambiguity, he immediately undertook a style of expression that was direct, firm and clear, without possibility for misinterpretation or unclarity. His closeness to the guru who had left his body some fifteen years earlier was a lesson to the monks, and an inspiration. §

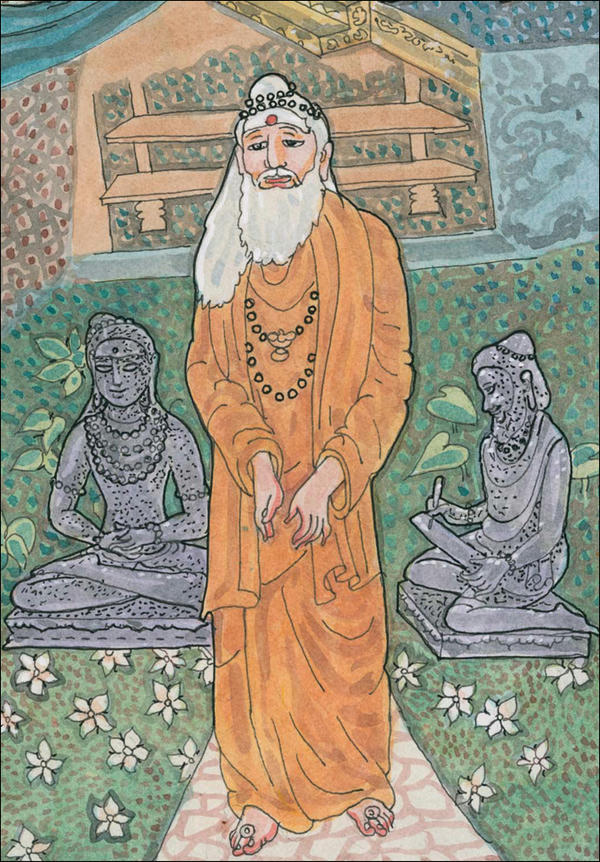

Two Tamil Treasures

By the late 70s Gurudeva, the white-haired American Hindu mystic, had effectively established an aadheenam, a traditional Tamil Saiva monastery-temple complex, the first ever in the West. He was officially the pontiff, the mahasannidhanam, of Kauai Aadheenam, and he took it as his charge to rearticulate Saiva Siddhanta for a new era, using modern English. In doing so, he rejected Puranic stories and the epics, which he, perhaps alone among Hindu leaders, boldly decried as philosophically inconsistent and mistakenly elevated to the status of scripture.§

He must have felt the authority of this spiritual seat, for he spoke with imposing certitude, and each of his declarations and edicts rang true to all who were with him. The works he produced in this period were full of fire and force, pure expositions, mystically authentic expressions of his guru’s religion. In a flattering twist, his writings found avid friends among the Tamil Saiva elite and were translated into Tamil, propounded as the clearest articulation of Saiva Siddhanta in modern times in any language. Dr. B. Natarajan, S. Ramaseshan, S. Shanmugasundaram and others were among the translators. §

Gurudeva promoted the yogic perspective of monistic theism, the religious theology, also known as panentheism, that embraces both monism and theism, two perspectives sometimes considered contradictory or mutually exclusive. He brought uncommon clarity to the pivotal Hindu concepts of karma and reincarnation, affirming that all souls are intrinsically good, that all karmas can be resolved, that Realization, as he had experienced it, can be attained, and that liberation from the cycles of birth and death is indeed possible.§

He propounded Saiva Siddhanta’s four-stage path to God, consisting of charya (service), kriya (worship), yoga (meditation) and jnana (wisdom). These stages, he said, are successive and cumulative, each one preparing for the next. He extolled temples and elucidated proper ways of worship. He also laid out in detail the disciplines of monastic and family life, including specific instructions about the control of sexual force. So that people could “catch the overview” of the world’s oldest religion, he summarized Hinduism in nine beliefs and Saivism in twelve. He put forward the Vedas and Agamas as Hinduism’s primary and revealed scriptures, but also acknowledged secondary scriptures like the Tirumantiram by Tirumular and the Tirukural by Tiruvalluvar (both ca 200 bce). §

In India during Tiruvalluvar’s time there was neither paper nor pens, so writing was accomplished with a stylus, the characters being scraped or scratched into a specially prepared leaf, called an olai leaf. Many ancient scriptures and literature were produced in this manner, and it is amazing that some of the original writings so made still exist today. Certainly no modern-day paper would have withstood the centuries so well! §

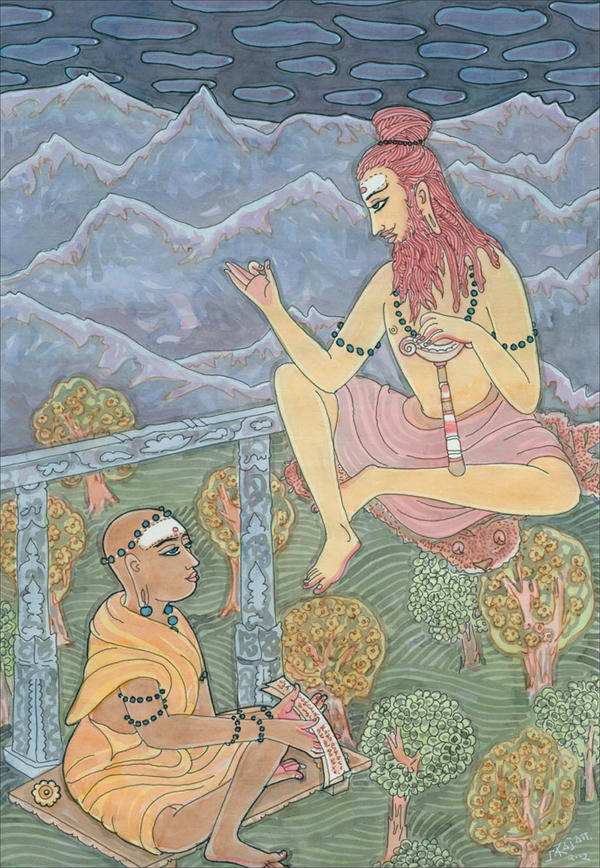

Again and again, he brought forward the traditional path of Saiva Samayam, and taught his monks, and later the lay families, the nuances of that path, its vocabulary and theology. Clearly, he wanted Yogaswami’s path to be deeply imbedded in his shishyas. Introducing the two life-sized statues which he had installed on the monastery grounds, Gurudeva described his view of these two cardinal scriptures in glowing terms.§

The statue of Saint Tirumular shows him sitting in the lotus posture, deep in meditation, while Saint Tiruvalluvar is seated with a small writing table on his lap composing his sacred verses with stylus in hand. His Tirukural speaks on virtuous living. It gives us the keys to a happy and harmonious life in the world, but it doesn’t give any insights into the nature of God, whereas, the Tirumantiram delves into the nature of God, man and the universe in its depths. Taken together, they speak to all Hindus and offer guidance for every aspect of religious life, the first addressing itself to the achievement of virtue, wealth and love, while the second concerns itself with attainment of moksha, or liberation. §

The Tirumantiram is a mystical book and a difficult book. The original text is written in metered verse, composed in the ancient Tamil language. Saint Tirumular is the first one to codify Saiva Siddhanta, the final conclusions, and the first one to use the term “Saiva Siddhanta.” It is a document upon which the entire religion could stand, if it had to. It is one of the oldest scriptures known to man. I was very happy to find that all my own postulations, gathered from realization, are confirmed in this great work. That is why this book is so meaningful to me—as a verification of personal experience and a full statement of the philosophical fortress erected and protected by our guru parampara.§

His 1978 talk, “Tirumantiram, Fountainhead of Saiva Siddhanta,” excerpted here, is a glimpse into his emphasis on this sacred text:§

One of the oldest of the preserved theologies of Saivism available to us today is that of Saint Tirumular. Of course, his was not the first theology, just one of the oldest to be preserved. He did not start anything new. His work, the Tirumantiram, is only a few hundred years older than the New Testament. He codified Saivism as he knew it. He recorded its tenets in concise and precise verse form, drawing upon his own realizations of the truths it contained. His work is not an intellectual construction, and it is not strictly a devotional canon either. It is based in yoga. It exalts and explains yoga as the kingly science leading man to knowledge of himself. Yet it contains theological doctrine and devotional hymns. It is the full expression of man’s search, encompassing the soul, the intellect and the emotions.§

Saint Tirumular was a Himalayan rishi, a siddha, sent on mission to South India to spread the purest teachings of Saivism to the people there. Hinduism is a missionary religion. Everyone within it, myself included, is on a mission or is purifying himself through sadhana enough so that he can be given a mission for the religion from some great soul, or a God, perhaps. This is the pattern within Saivism, and Saint Tirumular’s mission was to summarize and thereby renew and reaffirm at one point in time the final conclusions of the Sanatana Dharma, the purest Saiva path, Saiva Siddhanta.§

Today we hear the term Siddhanta, and various meanings of the word may come to mind. For some, perhaps their immediate thought would be Meykanda Devar and his interpretation of Saiva Siddhanta. For others, some concept of a philosophy halfway between Advaita-Vedanta and Dvaita, a vague area of unclarity, and for others various literal translations of the word such as “true end,” “final end” or “true conclusion.” §

The term Siddhanta appears for the first time in the Tirumantiram. The word anta carries the connotation of goal/conclusion, as does the English word end. Tirumular’s specific use of the word was “the teachings and the true conclusions of the Saiva Agamas.” And these he felt were identical with Vedanta or “the conclusions of the Upanishads.” In fact, he makes it very clear that pure Saiva Siddhanta must be based on Vedanta. Siddhanta is specific, giving the sadhanas and practical disciplines which bring one to the final Truth. Vedanta is general, simply declaring in broad terms the final Truth that is the goal of all paths. §

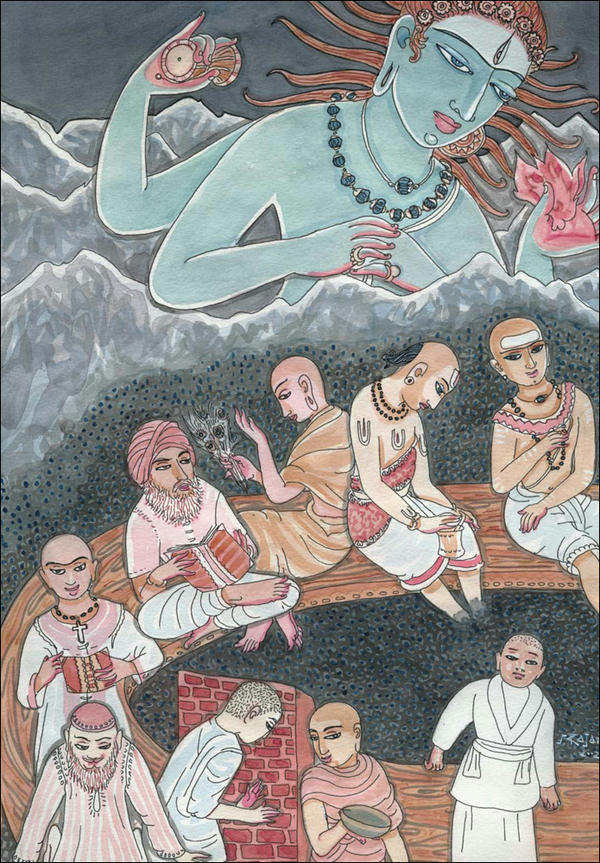

Here is depicted the human spiritual path, with Saivite, Vaishnavite, Buddhist, Sikh, Christian, Muslim, Jewish, Jain and Taoist seekers. All these and more faiths are respected by Saivism, which sets no limits for its tolerance.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •§

There are those who would intellectually divide Siddhanta from Vedanta, thus cutting off the goal from the means to that goal. But our guru parampara holds them to be not different. How can we consider the mountain path less important than the summit to which it leads us? Both are one. Siddhanta and Vedanta are one also, and both are contained in Saiva Siddhanta. That is the conclusion of scripture and the conclusion of my own experiences as well. The Suddha Siddhanta of Saiva Siddhanta is Vedanta. §

Vedanta was never meant to stand alone, apart from worship, apart from religious tradition. It has only been taken in that way since Swami Vivekananda brought it to the West. The Western man and Western-educated Eastern man have tried in modern Vedanta to secularize traditional Sanatana Dharma, to take the philosophical conclusions of the Hindu religion and set them apart from the religion itself, apart from charya and kriya, service and devotion. Vedantists who are members of other religions have unintentionally sought to adopt only the highest philosophy of Hinduism to the exclusion of the rich customs, observances and temple worship. They have not fully realized that these must precede yoga for yoga to be truly successful. Orthodox Hindus understand these things in a larger perspective. These same problems of misinterpretation must have existed even in Saint Tirumular’s time, for he writes that “The pure and illustrious Siddhanta is Vedanta” (Verse 1422). “The bhakta of the eulogized Suddha Saivam is the eternal one. He is the blemishless jnani and ruler of radiant jnana. He is the truly liberated, in whom wisdom has dawned and who is stable in the middle position of the Vedanta-Siddhanta teachings” (Verse 1428).§

It may be that Saint Tirumular pioneered the reconciliation of Vedanta and Siddhanta. But what is the Vedanta that Tirumular was referring to? Shankara, with his exposition of Vedanta, was not to come for many centuries. Thus, concepts such as Nirguna and Saguna Brahman being two separate realities rather than one transcendent/immanent God, the absolute unreality of the world, and the so-called differences between the jnana path and the previous stages had not yet been tied into Vedanta. The Vedanta that Tirumular knew was the direct teachings of the Upanishads. If there is one thing the Upanishads are categorical in declaring it is Advaita, “Tat Tvam Asi—Thou art That,” “Aham Brahmasmi—I am Brahman.” And when Saint Tirumular says that Siddhanta is based on Vedanta he is using Vedanta to refer to this Advaita, which according to him must be the basis of Siddhanta. This is perhaps one of the most important essentials of Tirumular’s Siddhanta to be brought forward into the Siddhanta of today, for it did, in fact, stray from the rishi’s postulations.§

To bring the pure path of Saiva Siddhanta to Kauai, Gurudeva introduced the Tirukural of Tiruvalluvar and the Tirumantiram of Tirumular to his monks and shishyas, commissioning life-size granite murtis of the two Tamil saints.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •§

That is why we occasionally use the term “Advaita Saiva Siddhanta.” It conveys our belief in the Siddhanta which has as its ultimate objective the Vedanta. It sets us apart from the Dvaita Saiva Siddhanta school of interpretation begun by Meykanda Devar which sees God and the soul as eternally separate, never completely unified. It is not unusual to find two schools, similar in most ways, yet differing on matters of theology. In fact, this has been true throughout history. It has its source in the approach to God. §

On the one hand you have the rishi, the yogi, the sage or siddha who is immersed in his sadhana, deep into yoga which brings forth direct experience. His conclusions will always tend toward Advaita, toward a fully non-dual perception. It isn’t even a belief. It is the philosophical aftermath of experience. Most satgurus and those who follow the monastic path will hold firmly to the precepts of Advaita Saiva Siddhanta. §

On the other hand there are the philosophers, the scholars, the pandits. Relying not on experience and ignoring yoga, they must surmise, postulate, arrange and rearrange concepts through an intricate intellectual process in an effort to reason out what God must be like. These are not infrequently the grihasthas and their reasoning leads them to one or another form of Dvaita Saiva Siddhanta. These are both valid schools. They are both traditional schools, and comparisons are odious. But they are very different one from the other, and it is good that we understand those differences.§

We must understand the difference between the Self-God, Parasiva, and the soul. Many people think that the Self is something that you get. You pursue it and after a while you get it, like you get something in the world. But the Self is not separated from you by even the tiniest amount. You cannot go someplace and get it and bring it back. The formless, transcendent Self is never separate from you. It is closer than your heartbeat. §

God Siva is called the Primal Soul because He is the perfect form, the original soul who then created individual souls. The individual soul has a beginning, and it has an end, merging with God. It has form as well. All form has a beginning and an end. The Absolute Self, Parasiva, is formless, timeless, endless and beginningless. All things are in the Self, and the Self is in all things. Many people think of the Self as an object to be sought. You start here and you go there, and you get the Self. You pursue it today; and if you don’t get it today, you try again tomorrow. It’s different than that. It comes from within you more as a becoming of your whole being than something that you pursue and get. And yet you seem to pursue it, and seem to get it. It is very difficult to explain.§

The individual soul is different. The soul has a form. The soul is form, a very refined and subtle form, to be sure, but still a form and form obeys the laws of form. The soul has a beginning in Lord Siva and an end in union with Him. The purpose of life is to know God, your very Self. This is the end of all religions, of all religious effort. This is why we say that religion is this process of lifting ourselves up, attuning our minds to the laws of life so that we become stronger and more mature beings. We become higher beings, living in the higher chakras, and we come closer and closer to God. God doesn’t come closer to us. How will God come any closer? He is closer to you right now than your own thoughts. He is nearer than breathing, closer than hands and feet.§

I shall explain the soul in yet another way, for I see a questioning look in some of your faces. Man has five bodies, each more subtle than the last. Visualize the soul of man as a light bulb and his various bodies or sheaths as colored fabrics covering the pure white light. The physical body is the outermost body. Next comes the pranic body, then the physical body’s subtle duplicate, the astral body. Then there is the mental or intellectual body in which one can travel instantaneously anywhere. §

Then comes the body of the soul, which I term the actinodic body. This is the body that evolves from birth to birth, that reincarnates into new outer sheaths and does not die when the physical body returns its elements to the Earth. This body eventually evolves as the actinic body, the body of light, the golden body of the soul. This soul body in its final evolution is the most perfect form, the prototype of human form. Once physical births have ceased, this soul body still continues to evolve in subtle realms of existence. This effulgent, actinic body of the illumined soul, even after nirvikalpa samadhi, God Realization, continues to evolve in the inner worlds until the final merger with Siva.§

I like to say, “God, God, God.” There is one God only, but man’s comprehension of That is helped by consciously exploring the three aspects of the one Divine Being: the Absolute, Pure Consciousness or the Self flowing through all form, and the Creator of all that is.§

Lord Siva is the Absolute Self, Parasiva, the timeless, formless, spaceless Reality beyond the mind, beyond all form, beyond our subtlest understanding. Parasiva can only be experienced to be known, and then it cannot be explained. Lord Siva is pure consciousness, the substratum, or Primal Substance of all that exists. He is the Energy within all existence. He is Satchidananda, or Truth, Consciousness and Bliss, the Self that flows through all form. Lord Siva is the Primal Soul, Maheshvara, the original and most perfect Being. He is the Source and the Creator, having never been created. He is the Lord of all beings. He created all souls out of Himself, and He is ever creating, preserving and destroying forms in an endless divine dance. When I was nine years old, I was taught that Lord Siva is God—God the Creator, God the Preserver, and God the Destroyer. To this day I know and believe that Siva is all of these, Brahma, Vishnu and Rudra. These are the final conclusions of Saivism, the Sanatana Dharma. §

You must all study the great scriptures of our religion. These divine utterances of the siddhas will enliven your own inner knowing. The Tirumantiram is similar to the Tirukural in many ways. You can teach them both to the children and apply their wisdom to everyday life. You can use them for guidance in times of trouble and confusion, and they will unerringly guide you along the right path. You can read them as hymns after sacred puja in your home shrine or in the temple precincts. Each verse can be used as a prayer, as a meditation, as a holy reminder of the great path that lies ahead. §

It is a difficult work, but don’t be discouraged by that. Just understand that it could easily take a lifetime, several lifetimes, to understand all that is contained in this scripture, that it is for those deep into their personal sadhana. It was given by the saint to those who fully knew of the Vedas and the Agamas, and to understand it you, too, will have to become more familiar with these other scriptures, slowly obtaining a greater background.§

It is interesting to reflect on the parallels, how Saint Tirumular was sent by his Himalayan guru to the South to spread Saiva Siddhanta to the generation of his day, and how Gurudeva, sent back to the West by Yogaswami to build a bridge between the East and the West, did much the same work for today’s Saivite seekers around the globe. Both men took Saivism’s cultural and spiritual treasures from one culture and one language to another, drawing upon their deepest realizations to unravel, summarize and explain, bringing Saivism forward in a new era.§

Gurudeva’s love of Tirumular and his deeply mystical verses derived in part from the saint’s uncompromising philosophy of oneness and in part from the bold Saivism expressed. In every talk for years he would quote Tirumular and, with a wry smile, note how happy he was to find a scripture that was in consonance, perfect agreement, with his own realizations. Here are some verses from the Tirumantiram. §

In the distressed world existing in the midst of the ocean,

Seeking the lustrous inner light residing in the body,

One can experience in the waves of the expanding sea,

The inner Lord placed in the body. 3028§

Being the inner light of the three great lights [Sun, Moon and Fire],

The Lord of the celestials stands as their intelligible bodies.

Leaving the great lights, in the limited space

He follows in compassion as the minutest of all. 3029§

He is the consciousness; He is the life;

He is the embracer and He is the act of sulking.

He is the imponderable; yet one can think of Him;

He is akin to the pollen of a flower. 2857§

The Lord with flowing matted locks bedecked with konrai flowers,

Is mingled everywhere as the subtle being;

The eight cardinal directions, the worlds above and below

Are centering ’round Him in this manner. 3042§

One day in 1977 he called a few senior swamis to his office and asked them to read to him from another South Indian scripture, the Tirukural. He knew Yogaswami had given great import to this text by the weaver saint of Mylapore. It was a Tamil masterpiece, full of insights into the human condition and lifestyle principles, learned by schoolchildren even today; but its content was not much known in English. The swamis showed him a new translation of the classic into British English. It sounded quaint and artificial to his ears. He took the book, read several verses aloud and paused on one to comment, “It’s nice, but what does it mean exactly?’’ The meaning was discussed. Tamil dictionaries were consulted, and after half an hour an attractive rewording of the rather turgid prose translation was achieved. §

Gurudeva was so delighted to have the meaning succinctly given that he gave two swamis the mission of translating the entire Tirukural from the original Tamil into modern American usage, striving for perfect clarity of expression. They began that same day, as was Gurudeva’s style. Though a relatively small work, just 1,080 couplets (the monks did not translate the final 250-verse section, which is a mildly sensuous love poem that seems to have been added later by another author), the ancient text was technically and linguistically complex; and it was twenty-two years later, with long interludes, that the full work was completed and published. In 1999 Weaver’s Wisdom was finally published, with its straightforward American English. Gurudeva’s summary at the end was, “We are actually living all the things Tiruvalluvar wrote about. His ideals have become our way of life.” §

He called for a comparison of the verses with previous translators, and, placing them side-by-side, smiled as if to say, “We did it.” For example, verse 15 speaks of the importance of rain. In 1886 Rev. G. U. Pope rendered it: “’Tis rain works all: it ruin spreads, then timely aid supplies; as, in the happy days before, it bids the ruined rise.” Gurudeva’s swamis, adhering to the terse and direct Tamil, wrote: “It is rain that ruins, and it is rain again that raises up those it has ruined.” Verse 252 on meat-eating provides another example. In 1962 K. M. Balasubramaniam translated it as “The blessings of wealth are not for those who fail to guard. The blessings of compassion for the flesh-eaters are barred.” The swamis translated it as “Riches cannot be found in the hands of the thriftless, nor can compassion be found in the hearts of those who eat meat.”§

Saivism Finds a Modern Voice

In 1978, after a hiatus of several years when his time was consumed with establishing the Kauai headquarters, and now free from outside influences that had demanded so much of his time and netted so little in return, Gurudeva took again to prolific publishing. It started with a simple series of pamphlets, which he called Prasada, or grace-filled gifts. Then came the booklets, called Inspired Talks, published in the same style as the publications done in Virginia City. Though the monks printed these 16-24 page booklets from his upadeshas, which was his life-long manner of conveying his teachings, he wanted them to be elegant, and so asked that they be professionally typeset in Honolulu. §

It worked, until the invoice for phototypesetting came. Astonished by the $700 bill, Gurudeva refused to pay another nickel for type. Instead, he asked the publications team to explore ways they could produce their own phototypesetting in house. The timing was perfect, for the first such device had just been released, and Gurudeva flew to Oahu with the monks to secure the purchase of a Quadritek 1200 phototypesetting machine. This tool transformed the way the monks were to publish in the years ahead, putting into their own hands the ability to set type in any font, any style, and for a reasonable cost. §

The effect was galvanizing. Type began to flow in streams that swelled to rivers. The immediacy of it inspired Gurudeva. Each time he saw a talk he gave one day typeset the next, he went right back to work to produce another and another. This cycle was different than before, in that the teachings were purely Saivite. From his return to Lanka in 1969, 1970 and 1972, he had meditated on Saiva Siddhanta, talked about Saiva Siddhanta, lived Saiva Siddhanta. Now that which had been within him began pouring out in a hundred ways. §

Titles included Free Will and the Deities in Hinduism; The Hand That Rocks the Cradle Rules the World; Protect, Preserve and Promote the Saiva Dharma; The Two Perfections of our Soul; The Meditator, and more. Among the most popular and controversial was Hinduism, the Greatest Religion in the World. From the title, some feared it was a bigoted diatribe by a zealous believer claiming the superiority of his faith. But inside was a balanced summary of Sanatana Dharma, including a poignant statement on Hinduism’s innate and unique tolerance for other faiths, listed among many facets of its greatness. Here is an excerpt:§

Hinduism has been called the “cradle of spirituality“ and the “mother of all religions,” partially because it has influenced virtually every major religion and partly because it can absorb all other religions, honor and embrace their scriptures, their saints, their philosophy. This is possible because Hinduism looks compassionately on all genuine spiritual effort and knows unmistakably that all souls are evolving toward union with the Divine, and all are destined, without exception, to achieve spiritual enlightenment and liberation in this or a future life. §

Naturally, the Hindu feels that his faith is the broadest, the most practical and effective instrument of spiritual unfoldment, but he includes in his Hindu mind all the religions of the world as expressions of the one Eternal Path and understands each proportionately in accordance with its doctrines and dogma. He knows that certain beliefs and inner attitudes are more conducive to spiritual growth than others, and that all religions are, therefore, not the same. They differ in important ways. Yet, there is no sense whatsoever in Hinduism of an “only path.” A devout Hindu is supportive of all efforts that lead to a pure and virtuous life and would consider it unthinkable to dissuade a sincere devotee from his chosen faith. This is the Hindu mind, and this is what we teach, what we practice and what we offer aspirants on the path.§

Gurudeva developed A Catechism for Saivite Hindus and A Creed for Saivite Hindus, condensed summaries of the faith that he considered among his most important works. The catechism consists of questions and concise answers about life according to Saivism, and the creed consists of twelve beliefs summarizing the philosophy. Every word was carefully chosen, discussed with the senior swamis of the Order, explored and crafted so as to carry the force and spirit of Saivism into the minds of future generations. The work was ready a few days before Mahasivaratri, March 7, 1978. He then distilled the creed into an affirmation of faith, which was the shortest summation possible of the Saiva Siddhanta beliefs, to be repeated each day by his followers. It simply says, “God Siva is immanent love and transcendent reality.” §

The several stages of monastic life were documented and formalized for the future during this time, an ongoing effort of the senior swamis of this theological seminary, working closely with Gurudeva. From this work came the Aspirant, Supplicant and Postulant vow books of the Church. In April Gurudeva commenced the preparation of a definitive document for the lifetime vows of a Saiva sannyasin, this to be called The Holy Orders of Sannyas. It was the first time that the oral transmission of the dharma for the Saiva renunciate was ever assembled in a concise yet comprehensive document to guide the monks’ life and clearly delineate their ideals, disciplines and lifestyle. Gurudeva took this opportunity to have all of his sannyasins reaffirm and sign their vows in the new booklet, including a formal oath of entrance into his Saiva Siddhanta Yoga Order. He had first founded the yoga order in the late 50s, and now it was becoming the core of his work and mission.§

For ten years, from 1970 to 1980, we had lived upon this island of Kauai with no members, no students and no visitors. The only visitors were my shishyas on pilgrimage and close special guests of high calibre who enhanced the spiritual lives of the young monks, such as swamis, pandits, scholars and the like. During this period, the monks spent their time in scriptural research for our publications, including a deep study of the two schools of Saiva Siddhanta, the six schools of Saivism, the four denominations of Hinduism, and all the major religions of the world. They supported themselves in rescuing a failed beekeeping industry, which they regenerated from 300 to a total of 3,000 colonies all over the island. This gave them a wonderful means for developing relationships on the island at a grassroots level.§

Though rife with complex thought and mystical overtones, Gurudeva’s teachings were as simple as sand. He spoke of man as not being the body, the mind or the emotions; and brazenly declared, as had Yogaswami before him, that man is not man, man is God. Again and again he drilled into all who would listen that the inherent nature of the soul is divine, existing in perfect oneness with God. This identity of the soul with God always exists, ever awaiting man’s awakening into realization. Each of us is a perfect soul, he assured, living in a perfect universe. All of this, articulated now in the disciplined language of Saiva Siddhanta, had been said by him decades earlier when he gave his 1959 talk called The Self God. How far that talk went is another story, told by Gurudeva. §

In the years that followed, tens of thousands of copies of the little booklet called The Self God were printed in America and in Asia and have been widely distributed. To show just how widely, one day our car experienced a flat tire on a road outside a remote village in South India. As it was being repaired, we wandered about. People were passing by now and again. After a while, an elderly villager noticed us and inquired as to our “native place.” I handed him a little pamphlet to be polite. He looked at us, refused my offer and pulled a little booklet from his shirt pocket, saying, “I am in need of nothing more. I have all I need right here.” He held up my The Self God booklet. Having made his point to these strangers, he walked on, not knowing he had been speaking to the author. In India and Sri Lanka, it is often referred to as “the little gem,” and is highly regarded as an explanation of the inexplicable nirvikalpa samadhi.§