Chapter Twenty-Two

Moving to Nevada

On March 24, 1964, the great Satguru Yogaswami of Jaffna attained mahasamadhi. Kandiah Chettiar sent photographs of the cremation rites within days, rites attended by enormous crowds. Sri Subramuniya was visited by Yogaswami inwardly. Soon thereafter a power swept through the American shishya, and he seemed to take on a new force of spiritual authority. His devotees saw what was happening and began calling him Master Subramuniya, a name he would make legal years later. He spoke of that time: §

Yogaswami passed from his physical body in March, 1964. After this happened, I began receiving letters from Ceylon saying, “You have to come back now, because we need you as the guru here,” indicating that I was his successor. I felt that my mission was in the West. §

Master named 1965 “The Year of the Academy.” His mission was in the ascendency, and he longed to develop his property in Nevada as a remote retreat for himself and his monks. He began to make the four-hour drive from the San Francisco temple to the ashram more often, sometimes weekly. Seeing the need, members leased for him a black Cadillac. Nevada had no speed limits in those days, and he drove those remote roads himself, seldom exceeding 80 miles per hour. It was, for him, a meditation. §

The Wild, Wild West

The Mountain Desert Monastery was to become Master’s spiritual home and his publications center. It was just a quarter mile from the center of a cowboy town of 600 red-neck mountain boys and their families. The wooden boardwalks from 100 years earlier were still used, and the Bucket of Blood saloon opened early in the day. The heyday was long gone and the Opera House was a shell of its former self; but the town survived, barely, on a trickle of tourists who made the 24-mile drive uphill from Reno. They would gamble a bit, buy some trinkets, drink a beer and have their pictures taken in front of a wooden Indian. §

The locals did not know what to think of Master and his San Francisco yogis who had bought the famed brewery. It took a year to get acquainted. Locals did this by crossing to the other side of the street whenever the monks came to town, which they did daily to fetch the mail from the post office. They did it also by racing their motorcycles past the ashram and screaming foul language to intimidate the monks. It was a clash of cultures. Master thought hard about how to make this work. In the end he bought cowboy boots, a hat and bolo tie, and worked to befriend the locals. He would visit their businesses, buy their services and talk their language. It worked, mostly. §

The guru purchased an abandoned three-story brewery in Virginia City, Nevada, as a summer retreat; but it soon was turned into a monastery for his growing order. For ten years his young monks served and trained in the remote, sage-covered mountains.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •§

Still, the raucous motorcycle welcome wagon continued. So he directed one of the monks, an ex-paratrooper with firearms training, to buy a shotgun. When the bikers made their next dust-cloud foray down Six Mile Canyon Road, the monk opened a second story window and let fly two 12-gauge shots over their heads. Communication is a wonderful thing. The drive-bys ceased, and a new respect for the monks seemed to emerge. §

The monastery had to deal with another side of the local culture. Nevada is the only state in the union where prostitution remains legal, and the most famous brothel in the state was just a few miles away. More than once a shaven-headed monk would open the door only to be asked most embarrassing questions. They soon learned to discreetly direct inquirers “a little farther down the road.” §

Young men came from all walks of life, all parts of the country, to serve and learn from this living yoga master who understood the superconscious states of mind they had glimpsed. The monastery grew as the most ardent and qualified came forward, eager to follow the monastic path—twenty, then thirty and more. They slept on the dining room floor, the shed floor, in the hallways, the attic and the back porch—anyplace a sleeping bag would fit. §

The guru welcomed them all, thereby setting himself an enormous work—for those young men, in their early twenties for the most part, came with all the things immature men have: bad habits, heavy karmas, personal preferences, combative natures, sexual longings, unfulfilled desires, experiences suffered, lack of discipline. So their guru began the work of training them: how to dress, how to walk and converse, how to work with others, how to eat at the table and answer the phone. He gave them projects to harness their youthful enthusiasm. For this, the publications served well. §

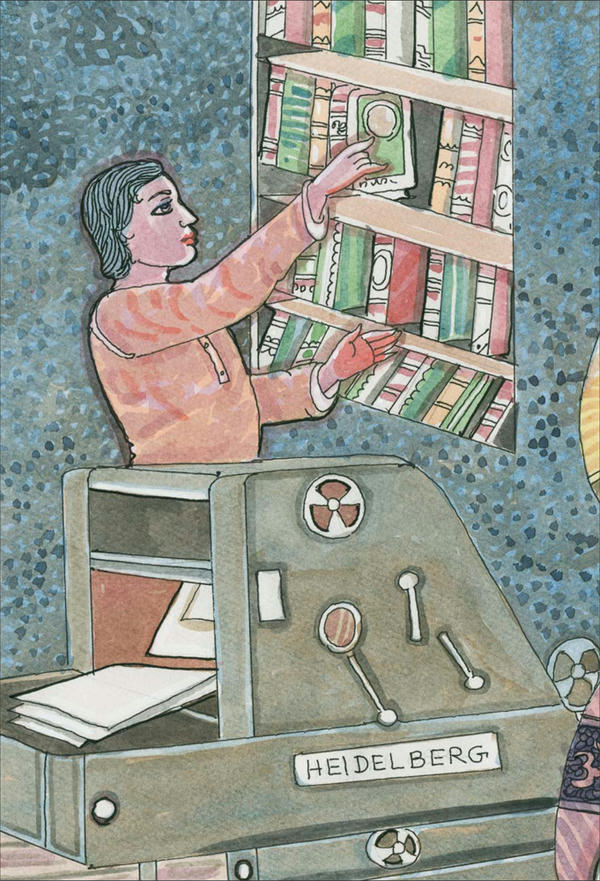

Master bought out a printing business in Oakland and had all its equipment—a functioning shop—moved to Virginia City. There it was set up under the care of the monastics on the ground floor of the building, with the presses and paper cutter in the brick-walled room that had served as the town’s Pony Express Station in the days of the Old West. §

Publishing continued to be a prime mission objective. The guru purchased state-of-the art printing equipment and set up Comstock House, his publishing arm, with monks printing and binding hundreds of thousands of spiritual books.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •§

Monks were sent to printing school in Anguine, California, to become apprentice pressmen, typographers and darkroom photographers. By 1968 the ashram became a humming, productive, professional printing and publishing center. Master Subramuniya turned out one small book after another, and the monks worked day and night to print and bind them. When exhaustion came, they crawled into sleeping bags at the foot of a Heidelberg press, only to rise again in a few hours, brew a pot of coffee and print until the sun came up. §

Master founded Comstock House, a publishing company; and through it the books swept across the nation, becoming some of the most popular spiritual writings of their time. The Clear White Light, The Fine Art of Meditation, Everything Is Within You, On the Brink of the Absolute, The Lotus of the Heart—one and then another came off those presses. Word spread of the monks’ skills, and soon the Nevada casinos were offering printing work—keno cards, restaurant place mats, corporate stationary and more—which, accepted for a time, helped the monastery support itself.§

Pushing the Monks to Perfection

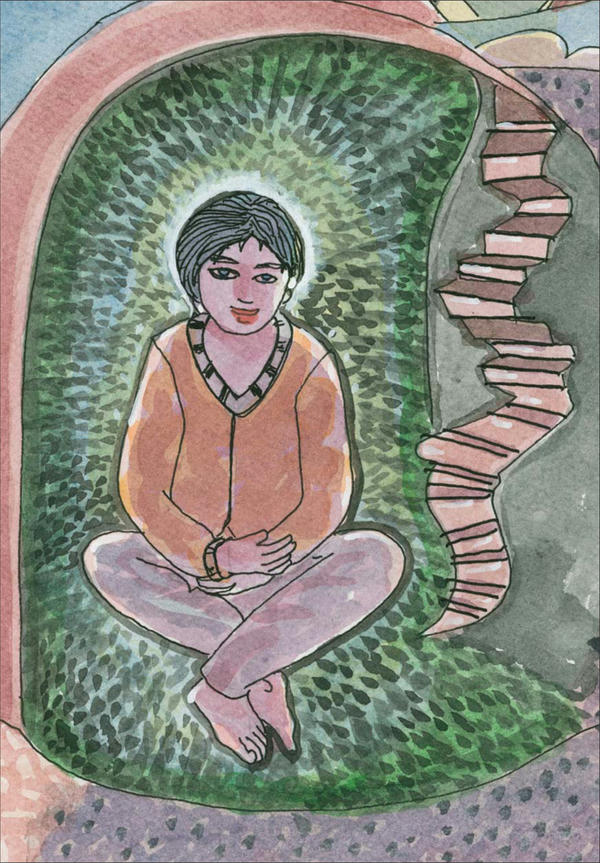

Despite all the publishing activity, it was the inner work that was central at the monastery, and Master Subramuniya set a demanding meditation schedule. Four times a day—at 6am, noon, 6pm and midnight—he ascended the narrow wooden steps to the spacious third floor loft where the monastery temple had been established, and there, without fail, all the monks would assemble for a full hour’s guided meditation. Babaji, the ashram’s Golden Retriever, never missed a session, curled up at Master’s feet. It was known to all that one could not miss a meditation. Master would be there without fail, and each and every monk would, too. The meditations were conducted in full lotus position, and it was unspoken but understood that no one was to move a muscle.§

One monk had difficulty enduring these long sessions day after day. His legs would cramp, and he could hardly keep his mind on the meditation. So, one day before the hour was called, he reached down to untangle his legs and relieve the strain. Master said simply, “Don’t,” directing him to stay in the lotus position until the end. The next day and the next, the same thing happened, until the young monk began to silently weep as he fought to keep his body still. §

Master took him aside and explained it was important for him to overcome this obstacle if he was serious, if he wanted a life of meditation. Master urged him to change his way of perceiving the pain, to see it as energy, as sound instead of pain. He said, “See yourself sitting on that sound as if sitting on a symphony. Try that.” He did, and after some days the pain subsided, the body made the needed adjustments, and he could sit still without discomfort. Such calls for willpower, for overcoming difficulties, whether physical, emotional, intellectual or karmic, came often from Master. §

Once, when trying to teach the monks how to control the heat of the body, he saw they were not getting it. So, he moved the 6am meditations outside. It was winter, and the high mountain snows drifted deep, so deep that in some years one could walk out a second story door onto the ground. That year was particularly cold. Each morning the monks followed their guru through the newly fallen snow to an open spot where they meditated together. They had only their robes and a woolen blanket to keep them warm, and these were pitiably inadequate. §

As the morning winds swept snow and frozen air past their defenses, they sat, in full lotus, shivering and seeking the silence within. The guru would then guide them to warm their bodies with their minds, to bring up the heat of the body, which in his Shum language is called alikaiishum. The monks worked with feverish intensity to learn the art their guru had put before them. This was no longer an exercise; it was a matter of survival. After some weeks, most had learned to raise their body temperature mentally—not because they wanted to, but because they had to. Such was the way of the guru in those days.§

Such training was intense for all the monks, as the guru took them through the personal transformations needed, the changes in their attitudes and their relationships, the resolutions of their past, the firming up of their work habits and meditative determinations. He taught them willpower, how to accomplish their goals, how to overcome obstacles, how to turn adversity and obstacles into success. §

In everything they did, he asked 108 percent. One hundred percent, he often repeated, is not enough, is not what you are capable of. Under this intense scrutiny and guidance, the monks flourished in their inner and outer lives—so much so that, decades later, the satguru would wonder aloud whether monks of succeeding generations would develop the same tenacity and strength as his first group had. §

From Virginia City, Master wrote this response to a seeker:§

Namaste! Your lovely letter arrived just as I returned to the monastery today from our India Odyssey pilgrimage to my ashram in Alaveddy, Sri Lanka, and eight other countries. That good timing indicates that you are on an inner beam, no doubt from the efforts already expended in your spiritual quest. From your letter, it is certain that you have exhausted the many dead-end trails on the path. Your decision to be a renunciate monastic is a good one. It is a big step and I know you have thought it over well. Times are changing. Dedicated souls like yourself are needed as helpers on the path in our monastic orders to stabilize and teach those who are seeking. It is time now for the Western mind to rediscover the vast teachings of Saiva Siddhanta Hinduism. §

I am going to give you the first of many challenges we may share together in this life. It is to meditate deeply every day for one full month on a talk I once gave to a small gathering of mathavasis, monks, at the San Francisco Temple. In fact, it was August 28, 1960. Like you, they were beginning to experience the blissful and peaceful areas of their inner being, and we spoke of enlightened insights one has on the very brink of the Absolute. You will be challenged by this assignment. Remember, the rewards are more than worth the effort required. §

It is my duty as your spiritual teacher to assure you that there will be trials. The sannyasin’s life is not easy. It will demand of you more than you ever thought possible. You will surely be asked to serve when tired, to inspire when you feel a little irritated, to give when it seems there is nothing left to offer. To drop out of this great ministry would not be good for you or for those who will learn to depend on you. A Hindu monastic order is not a place to get away from the world. You must teach us and yourself to depend on you, so that twenty or thirty years from now others will find strength in you as you fulfill your karmic destiny as a spiritual leader in this life. §

Therefore, read carefully these words. Weigh your life and consider well where you wish to devote your energies. The goal, of course, is Self Realization. That will come naturally. A foundation is needed first, a foundation nurtured through slow and arduous study, through sadhana performed and the demands placed by the guru upon the aspirant. This is a wonderful crossroad in your life. Do not hurry into it. Do this assignment and, should you wish a more disciplined and intense training, do sadhana. Settle your affairs of the world. Then we can sit together. Love and blessings, Master. §

Not far from the Mountain Desert Monastery lay an abandoned silver mine. The guru would send young monks to live in this deep cave for days at a time, teaching them how to see the inner light within the all-pervasive darkness.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •§

There is a cave down Six-Mile Canyon Road, perhaps a mile beyond the monastery—one of the hundreds of abandoned silver mines that honeycomb the region’s hills, but horizontally deeper than most. One can walk for half a mile into its chambers. When Master discovered the cave one day, he was thrilled, and immediately set up a program for his monks. Most often alone, but sometimes in pairs, he sent them to meditate in the dark chambers. Taking only water, no food, the monk would enter the cave, walk through the long tunnel, dodging the massive wooden supports that prevented cave-ins, until there was no light, then walk some more. Once inside the blackness of this space, he would settle down to stay for a day, for two days, as instructed, rarely more. He was to chant and meditate, nothing else—except, and this was the sadhana, to seek the light within, the clear white light of the mind.§

Sometimes, when meditating, one does not know if he is seeing the inner light or perhaps seeing the luminous space of the room beyond his closed eyes. But in a cave, deep in the Earth, there is no peripheral light. There is blackness. There is silence. There is nothing else. Monks would dive into themselves in that cave, distracted at first with the random intrusions of recent experience, of their projects back at the monastery, the paucity of food, whatever. But as the hours flowed by, the silence grew, and that silence worked well to bring them into the light of the mind. And when you see light in a darkened cave, you know it’s not coming from anywhere else; it is coming from you. §

A few monks returned to speak of extraordinary moments when the light coming from within also illumined the floor and walls of the cave, brightly enough for them to discern details of the tunnel, bright enough for them to walk out without turning on their flashlight. Such was the way of the guru in those days. Master wrote about the inner light shortly after these cave experiences: §

Remember, when the seal is broken and clear white light has flooded the mind, there is no more a gap between the inner and the outer. Even uncomplimentary states of consciousness can be dissolved through meditation and seeking again the light. The aspirant can be aware that in having a newfound freedom internally and externally there will be a strong tendency for the mind to reconstruct for itself a new congested subconscious by reacting strongly to happenings during daily experiences. Even though one plays the game, having once seen it as a game, there is a tendency of the instinctive phases of nature to fall prey to the accumulative reactions caused by entering into the game. §

Therefore, an experience of inner light is not a solution; one or two bursts of clear white light are only a door-opener to transcendental possibilities. The young aspirant must become the experiencer, not the one who has experienced and basks in the memory patterns it caused. This is where the not-too-sought-after word discipline enters into the life and vocabulary of this blooming flower, accounting for the reason why ashrams house students apart for a time. Under discipline, they become experiencers, fragmenting their entanglements before their vision daily while doing some mundane chore and mastering each test and task their guru sets before them. The chela is taught to dissolve his reactionary habit patterns in the clear white light each evening in contemplative states. §