Chapter Nineteen

Subramuniyaswami’s Youth

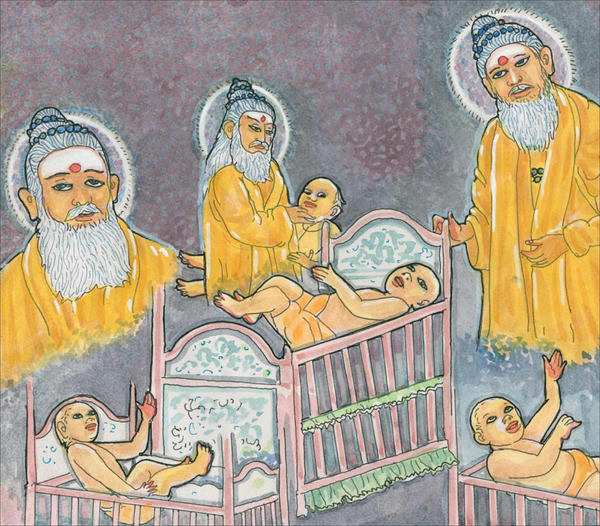

The first mystical experience that I can remember was as a baby lying in my crib. It had little bars up so you couldn’t fall out. All of a sudden, I was conscious of a tall, full-grown man standing over me in a serene, pale yellow robe. Then I became fully conscious of being this full-grown man looking down upon this little baby. Then I was conscious as the baby again, looking up into the face of this great soul. And then I was the tall person. Then I was the little baby looking at the tall person. It went back and forth and back and forth and back and forth. I realized that the tall man in the pale yellow robe was the body of the soul. I realized that as I continued maturing spiritually the soul body would finally fully inhabit the physical body. §

That infant, Robert Walter Hansen, who would later become Satguru Sivaya Subramuniyaswami, was born at the Fabiola Hospital in Oakland, California, on January 5, 1927, to Walter and Alberta Nield Hansen. He was raised with his younger sister, Carol, in a cabin on the secluded, forested shores of Fallen Leaf Lake, near Lake Tahoe, California. Walter, a taciturn man, was a native Californian whose parents were both from Denmark, and Alberta was born in Kansas of an English-born father. §

His mother and father were somewhat secretively involved with the medical school at Stanford University, though their life as caretakers of a remote log-cabin lodge gave little indication of why. Mysteriously, the medical school paid for all his mother’s funeral expenses when she died. Robert was never privy to what happened at Stanford, as his description of those days would later reveal: §

There’s actually no proof of this, but I’ve always felt from different hints and things that were said that I was an experimental baby, which they used to call at that time a “test tube baby.” I grew up with those thoughts in my mind. I believe that Grace Burroughs, who adopted me in dance and as a son, knew of my mother’s cooperation with the research department of Stanford University Medical Center. Those were the days when artificial insemination or test-tube babies were only a concept and in the experimental stage. I remember at birth looking up at Dr. Chapeau, a Frenchman, a neighbor of ours, and to this day feeling him as being close to me as a father. §

Lying in his crib only days after his birth, infant Robert Hansen had his first vision. Looking up, he saw the soul body of a tall, white-bearded man, and he knew instantly that this was himself in the fullness of maturity. Suddenly, he was the man watching the baby, then again the baby looking up at himself. Four times the observer changed.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •§

He reflected, late in life, that his lifelong dispassionate nature, a powerful sense of detached innerness, might have been the result of the unemotional manner of his conception and birth. §

Life was bucolic for the small family. The wild and remote Lake Tahoe area was one of America’s most beautiful regions, and tourists flocked to the rough-hewn lodge in summertime. Walter and Alberta were the host-caretakers, looking after the guests and the upkeep of the resort. But winters at 6,377 feet are severe; and the Hansens were alone for many months of the year, surrounded by old growth fir and pine trees and snow four to ten feet deep. They passed the seasons this way for years, far from the nearest neighbor, dependent on carefully garnered stores of canned foods and cords of firewood, stockpiled before winter set in. §

Despite the desolate location, the children had lots of attention, gifts and toys. There were always huge piles of presents under the Christmas tree. At family gatherings they were surrounded emotionally by twenty or thirty relatives, and both children had photographs taken almost weekly throughout their early years. §

Robert was three years older than Carol, and became her companion, caretaker and babysitter. He would make snowmen for her, instruct her in the fine art of snow travel on a wooden sled called Skootabog, down the gentle slopes behind the lodge, and teach her the ways of the forest which he had himself only recently learned. Brother and sister attended a one-room, log-built schoolhouse in which 23 students, of every age from six to sixteen, were taught by the same teacher. Their only wintertime connection to civilization was occasional mail and an old radio that brought them news and those sound-effects-laden soap operas sponsored by oil companies and Ovaltine. §

Robert spent most of his time playing. His father tried to interest him in carpentry, building a table, obtaining tools, but he wasn’t interested. He liked running barefoot in the snow, boating, skiing and snowshoeing in the winter. He played mostly on the trails and paths, or in the woods. In the summertime, Robert would swim out to a rock in the lake and meditate. He would stretch out on his back and go within until he felt he became the rock. Looking up, he would experience God pervading the sky and the rock, and all that was around him. §

“I’m All Right, Right Now”

Among Robert’s favorite radio shows was “The Lone Ranger,” a serial adventure that was broadcast from 1933 to 1954. In the story, a heroic masked Texas Ranger gallops on his horse Silver to right injustices, helped by his clever Indian partner, Tonto. The weekly half hour was addictively popular with kids eager to be enthralled, among them the Hansen duo, who never missed an episode. §

One cold December day in the early 1930s, Robert’s father took his son on a supply errand to the village of South Lake Tahoe, three miles away, to pick up the mail and stock the family pantry. They had a custom-made truck—black in color, as all automobiles were in that day—that had two large skis mounted in front instead of tires, and dual-wheel metal snow tracks in the rear, so they could drive on top of the lightly packed snows without a need for roads. It had a fabric roof, no side windows and the back was an open flatbed for carrying supplies. On this day, father and son were running late, and that was not good. This was the evening “The Lone Ranger” would be aired, and it was unthinkable that an episode would be missed. But the unthinkable was happening. It was a moment the young boy would remember the rest of his life. §

Quite often the snowmobile would become stuck in the snow. This might delay us an hour or two as my father worked to release it so that we could proceed. Each time we went to the village, on the way home I observed my thinking faculty being disturbed and worried for fear that we would not arrive home in time for me to listen to my favorite radio program. I hated to miss the sequence of the programs, such as “Captain Midnight,” “The Lone Ranger” and “Jack Armstrong, the All-American Boy.” §

This was the first time I became aware in the area of the mind that always worries. There I was, though, and I didn’t like it. I clearly remember mentally talking to myself and saying, “You are all right right now. We haven’t gotten stuck in the snow yet! Have we?” At that early age, I actually saw awareness coming out of the area of the mind that always worries and entering a total consciousness of here and now. Then awareness would leave the now and go into the past, and I would begin to think, “Four days ago we were delayed in the snow for about an hour and my father had a very difficult time digging out the snowmobile.” I saw my awareness travel into the past. Then I would repeat even more firmly to myself, “I am all right, right now. We are not delayed yet.” And again, I actually saw awareness travel right back to the present moment. §

This became one of my hobbies. The totality of the power of the eternity of the moment began to become stronger and stronger within me from that time onward, until whenever anything came along in the mind substance, I was able to handle it and work it out right from the now, instead of having my intelligence drift off into the future and try to work it out from that perspective or backtrack into the past and try to find a resolution there. All this and even more unfolded to me at that early age in such a beautiful and simple way. §

Young Robert’s mind seemed to take the best out of every experience, even then. But not all those early experiences were amenable to his gift.§

Church-going was culturally mandated in those days, and the children were no exception. He would ask the minister questions, but the minister would not answer. “So, why should I go?” he challenged his mother. She talked to the minister, who obligingly conceded, “Please don’t force him to come.” The compromise of nonattendance seemed acceptable to all, and Robert’s church and Sunday school days halted abruptly. §

Orphaned

When Robert was nine, his mother, who had all his life been a vivacious and adventurous woman who loved nature and plucked herbs from her own garden, took ill. He helped care for her, even in times of delirium. In July of 1937, she came under the care of Dr. Malcolm Hadden in Berkeley. As the months wore on, her condition grew more grave, and by early November, she was admitted to an Oakland hospital. On November 11, 1937, Alberta died of cerebral arteriosclerosis and chronic myocarditis, leaving the children, 10 and 7, in her husband’s sole care. She was cremated. §

Grace Burroughs, an intimate friend of the family who lived nearby with her husband, took over the job of mothering the children. Walter, alone and burdened by his wife’s death, raised Robert and Carol with Grace’s help. Life in those backwoods parts is hard enough when shared by a fit couple, but overwhelming when one is left with all the responsibilities. §

The family fared the winter as well as one might expect, but things were never the same. Walter grew morose, feeling the weight of his children’s needs as any father would. He began drinking heavily, making the rounds of Nevada casino bars with his children in tow. This was to be Robert’s first lesson on the powerful impact of sorrow. §

One day, months after his wife’s death, Walter was driven, for reasons unknown, to take a belt to his son. That beating would never be forgotten, and the two hardly spoke from that day, so traumatized was Robert by the cruel strapping.§

On December 9, 1938, Walter left the home to drive into town with Bill Burke, a local stonemason. The weather was bad and their truck was sideswiped, forcing it off the road and into a tree. Burke was killed instantly, but Walter managed to drag himself away, his chest crushed and both legs broken. A neighbor carried Walter back to the cabin, and that night they drove him to a hospital in Reno. Doctors worked to heal his fractured legs and ribs; but as the days passed he began to fail, and finally succumbed to pneumonia on December 14, at age 50. §

Walter’s estate went into a trust for the children. The funeral was held in Auburn, California, where Walter’s parents had been buried. Though the family begged him, Robert refused to attend. Days before his 12th birthday, he was an orphan. §

Robert made snowmen as he grew up in the woods. He discovered the eternal now at age nine, when he and his father got stuck in the snow in their half-track truck and it seemed he would miss his favorite radio show. He withdrew from his fear by assuring himself, “I’m all right, right now. It hasn’t happened yet.”

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •§

I can remember being hit twice in my life. Once with a ruler, two hits on the open palms. Then the father with a belt once. After that I would have nothing to do with him. I refused to go to his funeral.§

Late in life, when asked about his youth by his monastics, he shared: §

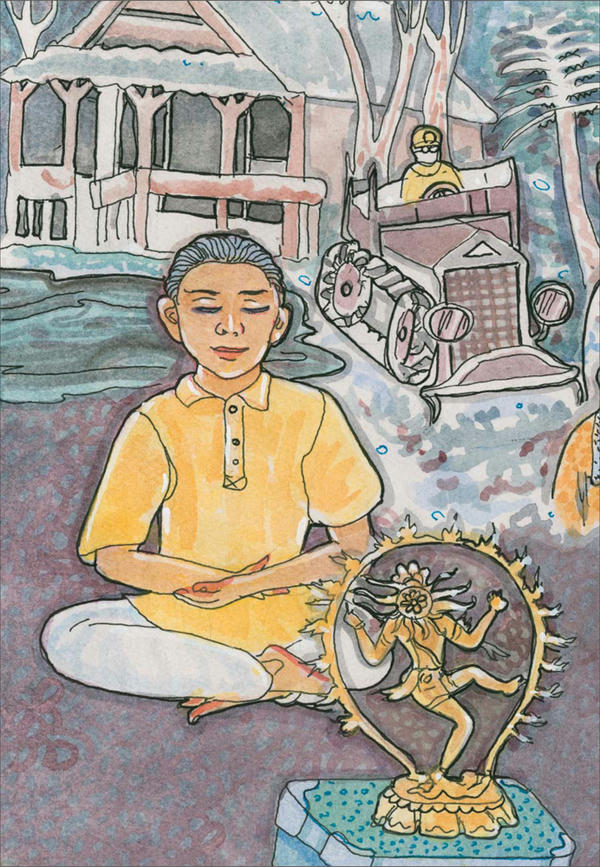

As a boy, I was disappointed by adults and said to myself, “I’m never going to listen to anyone older than myself.” And at that time being an orphan you could do whatever you want to—that’s the one good thing about being an orphan, you don’t have to listen to anybody. So, I listened to my own inner self and decided that I wanted to dance. And why was that? Because I was told God danced. Nataraja danced. I had already been taught pranayama, basic hatha yoga, when I was eight or nine years of age. Then during my teens, I learned attention, concentration and meditation. §

He was referring to the summers he spent with Grace Burroughs at her school of dance at Fallen Leaf Lake, in which his father enrolled him during the summer following Alberta’s death. Grace—an elegant, round-faced woman with an Oriental look born in Nebraska in 1895—had spent three years in the mid twenties touring the world with the Denishawn Dancers and a year or more in India as a palace guest of the Maharaja of Mysore, studying Indian dance, customs, art and philosophy. §

“I Want to Dance”

Grace trained Robert in Indian and European dance, Indian culture and the fine art of meditation. This cultural discovery enchanted Robert, and the artistry and discipline of dance absolutely mesmerized him. It gave him a purpose, a goal, his first as a young adult, and he threw himself into it with all his heart. Decades later he recalled:§

Robert was introduced to Lord Siva through Nataraja, the King of Dance. His teacher gave him a small Nataraja, which he placed on a large rock altar with candles.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •§

About the age of ten or eleven, I became aware of what I wanted to do when I grew up. “I want to dance,” I said. This came from deep within me. Music always moved the inner energy of the inner body and finally the muscles moved and the body would begin to dance. Dance, incidentally, in Hinduism, is considered the highest form of expression. That is why dance was used for worship in temples of ancient cultures. Through the esoteric forms of dance, you become acquainted with the movements of the currents of the physical body, the emotional body and the body of the soul. The meditating dancer, inspired by music, finds the inner currents moving first, and lastly the physical body. This releases his awareness into inner, superconscious realms of the mind in a smooth, rapid and systematic way. I started my life in the dance as the dance, and being the dance.§

The young artist was eager to learn, and Mrs. Burroughs was thrilled to have a focused student. She decided to teach him the Manipuri dance of India, a traditional style that depicts the forces of the natural world.§

Grace Burroughs, my first catalyst, was keenly interested in dance and in all the cultural arts of India. She was the first to bring an interest for Indian things to the West, mainly San Francisco, which was then a real center of culture. She brought artists over for concerts. She taught me the yogic and cultural practices she had been introduced to in India, in palace-like surroundings where religious Hindu music was constantly playing, meals served on trays, saris worn and the Mysore tradition carried forward, promulgated and taught in a royal and dramatic way. §

By the time I was twelve years of age, I knew how to eat with my hands, how to put on a dhoti, how to wrap a turban; this was my dress for the year to follow. I learned how to dance; Manipuri dance was taught at that time. She also carefully trained me in concentration and meditation. We would have to sit for hours in her chalet and look at the calm, glass-like lake and equate it with the calm of mind devoid of thought. We would also meditate after the ceremony of lighting the lights that surrounded the fire altar that I was trained to dance before as fire itself moving to the music, as the wind and breath of air moved the fire. I was taught how to meditate on the cosmos (that was a big word for me in those days), the stars, the galaxy, Lord Siva, the creator, preserver and destroyer of all mankind and all things—Lord Siva, God, raised foot, dancing to drums, the tandava dance that I had learned the last year.§

I was introduced to Siva with Nataraja images. Those early impressions, you know, remain in your mind along with all the long stories and conversations about India and the culture of India. The school had large collections of Indian fabrics and saris and dhotis and artifacts and so forth that I was exposed to. §

His early mentors brought Indian culture into Robert’s life, teaching him to wrap a turban and eat with his hands. His auntie took him to stage performances, modern and traditional, including psychic exhibitions where astral beings manifested using a substance called ectoplasm.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •§

Grace taught him much. She took to softly disciplining the boy when needed, not directly, but by leaving handwritten corrections in an agreed-upon niche in the stone altar. Robert would go there now and again, read her note and adjust accordingly. All very civilized.§

We never had a personal confrontation of correction. She always chastised me by leaving a note in a sacred place for me to read. Embarrassingly, I read it, took it within myself and corrected myself.§

After his father died, Robert moved almost completely into Grace’s world. Grace, an initiated Rosicrucian who knew much of the occult sciences, recognized the spiritual element in his dancing. In her presence Robert’s unfoldment began. It was to be completely different from his earlier years. They understood each other. She was fantastically eccentric, a real-life Auntie Mame.§

Grace wanted to become the guardian of the Hansen children, but the relatives, aware of the eccentricities of the artiste, would not hear of it. Instead, they appointed Robert’s Aunt Helen, whom he liked. She was a refined lady, and a Christian Scientist. When Helen realized she did not have the means to raise them, she found a family from her church. The couple, Melville and Flora Hamilton, continued the children’s upbringing in their Oakland Hills home, replete with beautiful gardens and a pond, from 1939 onwards. The children were given a background in Christian Science, and from it Robert learned of the healing powers of the mind, of the innerness of the spiritual path and of religious tolerance. §

Nevertheless, Grace Burroughs was the most influential force in young Robert’s life after his father’s death. She whisked him away to spend summers at her dance school at Fallen Leaf Lake in a chalet she named Beau Reve, “beautiful dream.” The rest of the year he could frequently be found at her place in Berkeley. She taught Robert Eastern dress and culture, as well as Manipuri dance and ballet, from age nine to fourteen. §

Grace also trained me to be a teacher of small children—four, five, six and seven years of age—and behold! I was on the faculty of the Grace Burroughs School of Dance! I must say, at that early age, I taught them well. They responded beautifully from what they learned, and I learned in teaching them.§

Finally, after I had absorbed everything I had to learn with my first catalyst, she introduced me to my second catalyst, Hilda Charlton, who patiently taught me how to center the whole being of the physical body, the emotional body and the spiritual body so that the inner light began to appear. With this catalyst, in Berkeley, California, I had my first inner light experience.§

“Then I Am God”

Hilda Charlton was deeply devotional and meditated regularly. She was psychically awakened and had premonitions of Robert’s going deeper and deeper into the teachings.§

Shortly after they met, she asked the teenager, “Do you know who you are?” The question puzzled him, and after a while he had to admit that he did not. Then she said, “Next time you come back, I want you to tell me who you are.” §

After thinking it over for a few days, he decided upon an intellectual answer, taken from something he had heard in Christian Science. On his next visit he told her, “I am a part of God.” She remained silent, then said softly and slowly, “If you were a bubble on the ocean—which would depict being a part of God—and the bubble burst, what would you be?” He knew the answer was “the ocean,” but then the real meaning came to him with a burst of understanding from within, and he said, somewhat wondrously, “Then I am God.” §

I studied with my second catalyst twice a week during these two most wonderful years. Never asking many questions, I just obeyed what was told to me to the very best of my ability. I was taught this at a very early age not to ask any questions. I was told one must absorb inner teachings. One has to become aware of where the teacher is within himself and look at what he is saying from that perspective. This is the way that the student learns to absorb inner teachings. Then they awaken within him and he complements them with his own inner knowing. My second catalyst also taught me how to see into the akasha and view great, actinic, inner-plane beings. §

My second catalyst was also well acquainted with various forms of mysticism, occultism and meditation. She taught me exactly how one leaves the physical body after putting the body to sleep. I learned of the astral body and how to work with and develop the experience of leaving the physical body in the astral body, while totally aware of the happening, turn around, look back at the physical body, see the silver cord which connects it to the astral body, and to travel astrally. §

This catalyst taught me how the inner energies of the seven chakras function as the physical body moves and is inspired through the different types of music. She gave me a tremendous training and exercise in the free form movement of the dance, in which one experiences no inhibitions of any kind. This was extremely good for me, at the age of fourteen and fifteen, because it controlled and transmuted the energies of the emotional area. §

Hilda Charlton drew Robert deeper into the mystical teachings, coming into his life at age 14. She was a deeply devotional person with natural mystical powers and premonitions. An exceptional teacher, she spent seven years taking the young seeker deeper into the disciplines of concentration and meditation, bhakti yoga and the art of giving. Later, she would travel with him to Ceylon. §

In 1945, as soon as he turned 18, Robert left his foster home and moved to San Francisco. Carol, who died in late 2007, stayed on until 1948. Brother and sister did not connect thereafter, and it was not until he was giving a book presentation at a Borders store in Redwood City, California, in 2000 that they would see each other again and speak a few words. So complete was Robert’s renunciation of his past.§

“Even the Gods Will Obey”

Hilda Charlton introduced him to his third catalyst, her dear friend, spiritualist Cora Enright, known as Mother Christney, who would become the most influential teacher of his youth. In the years that followed, she brought him into karma, raja and jnana yogas, taught him obedience and service to others, selflessness and the inner light. §

Standing just 5' 2", she did not quite reach Robert’s shoulder, but she was larger than life, aristocratic and outspoken. With snow-white hair, a cherubic face and long, flowing robes, she looked, some said, like an angel or fairy godmother. §

A kindly lady, she was also a tough teacher, demanding and sometimes domineering. She tested Robert severely and corrected him sternly, making him prove himself at every stage. He learned her ways and grew stronger in his spiritual commitments under her reign. She told her young charge, “When the spirit rises in command, even the Gods will obey.” And she schooled him in the arcane arts of spiritual leadership. He told of her style:§

Mother Christney would test all who came to her, requiring proof of their sincerity. If a person approached her wanting to study, she would hand them a credit card with no explanation. If they held it a moment and handed it back, she would move forward with them. If they took the card, turned it over and looked at the reverse side, she would say nothing, but they would never be invited back. Mother Christney was like my vishvaguru, teaching me all the ways of the world.§

Her Catholic background was completely unorthodox; at heart, she was a spiritualist, with immense psychic abilities. Though she had left the Church, she had frequent visions of the saints and often shared her otherworldly conversations. She could regale congregations and individuals with tales of psychometry, aura readings, Solar Biology, ectoplasmic manifestations and Christ consciousness. §

Mother Christney followed a mystical form of Christianity, one considered heretical to most Christians. It was an attempt to weave mystical truths normally found in Eastern religions into the structure of the more narrow Christian faith. Such mysticism was alive quite early in the Catholic Church’s history with the 3rd century philosopher Origen, and was reflected in more modern times in the Rosicrucians, Theosophists and Freemasons.§

In the century before Mother Christney’s life, Christianity had morphed in America, giving rise to new churches—the Mormons in 1830, Seventh Day Adventists in 1863, Christian Science in 1866, the Church of Divine Science in 1880, Unity Church in 1889 and Religious Science (also called Science of Mind) in 1927. These last three are part of the New Thought Movement, which emphasizes metaphysical beliefs concerning the law of attraction, healing, life force, creative visualization, personal power and the ideas that Infinite Intelligence or God is ubiquitous, spirit is the totality of real things, the soul is divine, high-minded thought is a force for good, all sickness originates in the mind and positive thinking has a healing effect. §

Her Christianity was not the traditional one. She took Robert to seances where the dead talked to the living, to theaters where performer-spiritualists amazed disbelieving crowds by bringing disembodied souls onto the stage and conversing with them. Some of these spiritualists manifested gems or predicted the future. Others made it possible for the audience to hear faint voices from the spirit world, amplified through cone-shaped trumpets. It was another world, and she wanted the young seeker to see it all. He would never forget these scenes, and took his own followers to experience them decades later.§

She was amazingly connected with the spiritual personalities of her day. In 1934 her home was the temporary ashram of a Sri Lankan guru, Dayananda Priyadasi (Darrel Peiris), who brought with him the Buddhist path of enlightenment. His ways charmed Mother Christney and inspired her to explore the Eastern path all the more, learning much she would pass on to her favorite student. §

She also knew Yogi Hari Rama, who was then the rage. He had landed in San Francisco in 1924 and toured the US, demonstrating levitation and teleportation, something Americans had not seen. Though he showed these powers, he always stressed that they were not needed for deeper spiritual attainments. He taught yoga in her Oakland home and became her guru, bestowing on her the name Mother Christney. §

Mother Christney was closely associated with Paramahansa Yogananda, serving on the board of directors of his Self Realization Fellowship. She studied Manly P. Hall and Edgar Cayce and met Indra Devi, who brought hatha yoga to Hollywood in the 30s. Mother Christney was impressed with Swami Bhagwan Bissessar, who came to America from Benares and who wrote the following affirmation for his devotees:§

O Thou, the Absolute, the Infinite, the only Reality, give me wisdom and faith so I may open the portals to my illimitable powers. Om tat sat Om. The portal of my mind is now open to the inflow of spiritual knowledge. I am one with the Absolute, united and inseparable, and the help of the Elder Brothers is mine.§

These Indian yogis and swamis brought with them the teachings of reincarnation, of an all-pervasive Divinity, of God within man, and man as being more of spirit than of body and mind. They taught the powers of pranayama and affirmation, the rigors of meditation and the elevation of consciousness. Mother Christney moved among them and absorbed the wisdom they brought from India and Ceylon, and that enabled her to ground her teenage prodigy in the subtleties of the Eastern path. §

Their relationship would span the next 24 years of Robert’s life, beginning with her mentoring him in her vast encounters with religion and mystical teachings, and ending with his looking after a frail friend. During the mid-60s, he stayed at her Oakland home on weekdays, helping with housekeeping and shopping, returning to San Francisco on weekends to manage his temple.§

My third catalyst was wonderful and patient. She taught me the psychology of the vibratory rates of color and how to read an aura, understand the meaning of each color and combination of color within the aura and how to equate them with the moods and emotions and thinking faculty of the person. She taught me a method of character delineation in the understanding of human nature, the way people think, the way they act, and the inner, subconscious motivation.§

She told me about the guru and said that one day I would meet my guru. But before I met my guru I would have to had realized the Self. She told me that I would find my guru on the island of Ceylon and that I must go there and study and that this was my next step. At that time, I was meditating two hours every day, right by the clock, just sitting there without moving, going in and in and in, trying to fathom the intricacies of what I had been learning and the purity and simplicity of the Self.§

In the second year of training, I was intricately taught to understand the actions and reactions of people, how they moved, how they thought, how they acted. I was taught to be so observant with the powers of concentration that I would actually know by the movement of the mind or physical body of someone all about their inner attitudes and how they lived at home.§

During the third year of training, I was taught how to test students inwardly and outwardly to determine if they were mystically inclined or just intellectually interested in the teaching. Then we went on into the study of thought forms and the feeling and meaning of various thought forms in meditation which one would see through his inner faculty. I began to know what a person was thinking about and his motivation for flowing awareness into that area of the mind where that collective thought substance occurred.§

My third catalyst also advanced me through the study of great beings who live in the inner areas of the mind, beings so developed in their nerve system that they no longer need the use of the physical body to function and communicate with humans. Similarly, I studied great beings who have physical bodies but function deep in meditation, helping those who meditate as a kind of spiritual mission, as a father and mother would oversee the emotional and physical maturation of their children.§

My third catalyst on the path had a thorough training in mysticism from a very early age with the American Indians in Nevada, and then with Swami Bhagwan Bissessar from the Himalayas, Yogi Hari Rama of the Benares League, and from the wonderful being I was about to meet on the island of Ceylon, my fourth catalyst on the path.§

All of this time I can’t remember having asked many questions or entering into discussion. I do remember once, however, when I was a bit externalized and the subject matter was not quite clear to me, I did want to discuss it. I was cut very short with the statement, “There will be no discussion.” I never did that again. When listening to inner teachings from a teacher who teaches in that way, if you miss a sentence or something is not quite clear, wait a few minutes and on the playback the clarity will come from deep within yourself. I learned this at a very early age. This is the way mystics are trained. There is no discussion. There are no questions. There is plenty of help on the inside from great unfolded souls, helpers on the path, enabling us to do this.§

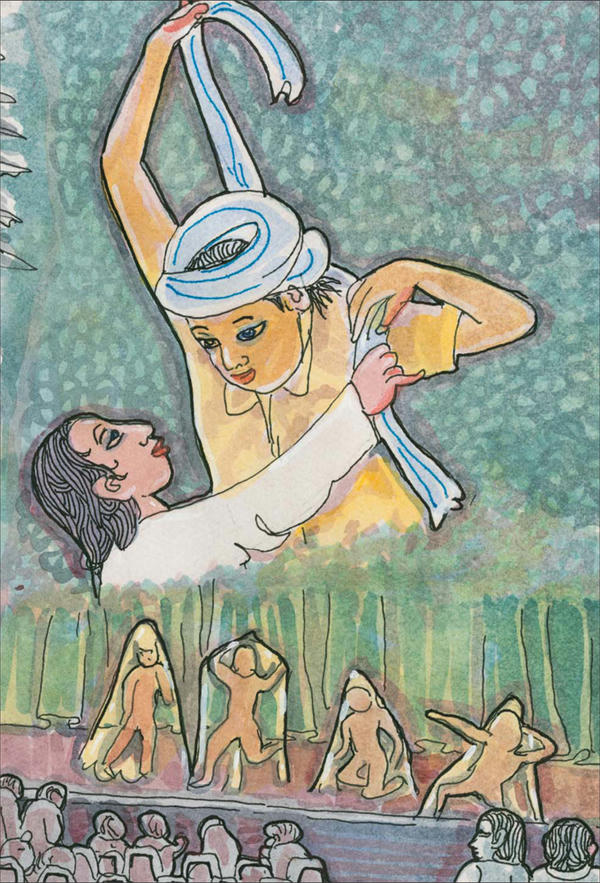

Robert’s performances were received with critical acclaim and popular applause. He would later relate that, looking out into the elite audience, he could see diamonds sparkling in the dark.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •§

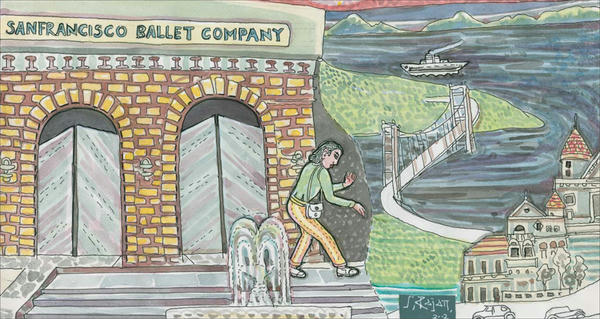

The San Francisco Ballet

At age sixteen, Robert entered the San Francisco Ballet School for an even more intensive training in classical dance. Within two years, he qualified himself as the premier danseur of the San Francisco Ballet Company, touring with them for two seasons throughout the United States and Canada. His training in yoga and meditation continued without a break. When in San Francisco, he would meditate two hours a day at the Presbyterian Church on Folsom Street, not far from the Ballet Company.§

This was one of America’s most prestigious ballet companies, and the competition was tough. Robert worked hard at his craft, driving his body for many hours a day to gain the strength and stamina a performer at that level requires. He worked out with weights and could bench-press 175 pounds at age seventeen, a necessity for lifting his partners aloft. Study, memorization, and practice, practice, practice. That was his day, his week and month. §

To push his skills to their limit, he hired a trainer and asked him to critique his dance, quipping decades later that “I paid $20 an hour to have a man criticize me, not to point out what I was doing right, but what I was doing wrong.” And that was when $20 was serious money.§

The company traveled, as entertainers do, mostly by bus and train. It was here, he later said, that he acquired his love of travel and his military precision in packing for a journey, which he could do in minutes. He performed at local theaters and entertained the troops at USO shows. America during these years was deeply immersed in World War II. §

The up-and-coming star ran with the best artists. No less than Ruth St. Denis and William Christensen choreographed his work, and he danced on stage with Italian divas and American stars. He moved with fine singers and musicians, and teamed up with opera singer Althya Youngman. §

While the troupe was performing in Southern California, Robert took the opportunity to meet with one of the day’s foremost gurus in America, Paramahansa Yogananda, at the Pacific Palisades center of the Self Realization Fellowship. Robert met the Indian teacher about the time he published Autobiography of a Yogi. Yogananda was kind, and on each of the teenager’s three visits thrust upon him an armful of literature and books. This was Robert’s first direct encounter with the spiritual giants of the East. §

At the height of a meteoric career, Robert’s spiritual life called. At nineteen, he left the ballet company and sailed under the Golden Gate Bridge on a merchant marine vessel, voyaging to India and Ceylon in search of his guru.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •§

Dance demanded most of his time and effort, but at night he turned inward. The world retreated and he meditated and studied the spiritual books he had, which were few. He was of a nature that mere reading was not rewarding—he would have to practice, explore, prove to himself the merits of what each teacher offered. §

That proved challenging when someone gave him a copy of a petite book by Patanjali, The Yoga Sutras. He dove into it, unraveling its arcane language, following its subtle directions and practicing, practicing, practicing, as he had with the dance, the yoga disciplines described by the Indian yogi. It was his initiation on the yoga path and his first understanding of superconsciousness as seen by the Eastern masters.§

Dance was flourishing in the young artist’s life. He loved the drama of it all, the sophistication, the social interaction, even the pomp and glitter. But dance was much more to him. It was a study of energy, of the mastery of life force, of how the spirit could move the material and thought could manifest action. He studied how the astral body moved first, and only then did the physical respond. He explored the life force in movement and the relationship of body and mind, a study that was not mere speculation but the science behind his artistry. Dance, to Robert, was the most divine of human expressions, the highest form of creativity. It was the only creation where the creator and the creation were truly one. The dancer was the dance just as the yogi is the cosmos. It was this inner aspect of dance that enthralled him even more than the stage lights.§

Those stage lights. The young performer delighted in the audience. When called to bow for an encore, he would move out with his long-legged gait and graceful arms and hands, knowing the effect each move, each gesture had on the audience. Flowers would fly onto the stage, the roar of unbridled applause would fill the hall and he would stand, marveling at the wealth that sat before him, all those diamonds and sapphires, all those thousand-dollar gowns and hand-tailored tuxes. To young Hansen, raised in humble and isolated surroundings, this adulation seemed to be the highlight of his life. But he would receive still greater tribute decades later, during visits to Sri Lanka, India (especially Tuticorin), Malaysia, Mauritius and other countries.§

He had reached the heights of dance. He had become the performer of classical solos and duets with ballerinas from Europe and South America, the headliner and star. He began talking of another journey, a journey to the East—the East that Grace Burroughs had intimated to him, the East that he saw in Swami Yogananda.§

Mother Christney was part of those conversations, and she had contacts in Ceylon. She sensed he needed more advanced spiritual guidance than she could provide; and she felt that Dayananda, the Sri Lankan Buddhist mystic, could be his next mentor on the path. §

Inspired by her encouragement, Robert started to ponder the practicalities of it. How would he get there? What would he do once he arrived? He knew no one and had little money, apart from a $700 a year stipend his parents had left him. The solution unraveled slowly. They would create the American-Asian Cultural Mission, touring India and Ceylon, singing and dancing and sharing their arts. He enlisted Grace Burroughs, singer Althya Youngman, composer-pianist Alva Coil and Hilda Charlton, dancer and mystic. As the plan solidified, Robert resolved to devote himself fully to its success. At the height of his career, only nineteen years old, he walked away from the San Francisco Ballet Company, never to return.§

Right at the top of my dance career, I followed the advice of really professional people who said, “You should stop when you’re on the top of your career.” I was sent by one of my teachers to Sri Lanka to find my guru, because I was very anxious to find my guru. I was deep in the study of all of Vivekananda’s teachings. I was listening to lectures at the Vedanta Society and meeting the swamis there and meeting Paramahansa Yogananda. I didn’t find my guru in any of them.§