Chapter Fifteen

“We Know Not”

Siva Yogaswami’s teachings, rife with esoteric insights about nothingness and not knowing, perplexed many an outsider. In life, the normal emphasis is on acquiring knowledge, or replacing a lack of knowledge on a subject with knowledge. We purchase a new computer. Knowing little about it, we read the manuals, talk to experts and end up acquiring enough information to use the computer. We have replaced a lack of knowledge with knowledge. §

Yogaswami’s approach, dealing as it must with spiritual matters, is the opposite. We start with intellectual knowledge about God and strive to rid ourselves of that knowledge. When we succeed, we end up experiencing God. Why is this? Because the intellect cannot experience God. The experience of God in His personal form and His all-pervasive consciousness lies in the superconscious or intuitive mind. And, even more cryptic, the experience of God as Absolute Reality is beyond even the superconscious mind. §

Acquiring clear intellectual concepts of the nature of God is good, but these concepts must be eventually transcended to actually experience God. Sam Wickramasinghe recalls how Yogaswami drove this truth into one man’s heart:§

The turning point in Swami Gauribala’s life came when he returned to Ceylon and journeyed to Jaffna. A lifelong bibliophile, one morning he was browsing through the spiritual section of the Lanka Book Depot on KKS Road in Jaffna town when an old, white-haired and rather wild-looking stranger suddenly snatched the book from his hands and said, “You bloody fool, it’s not found in books! Nee summa iru!” (“You be still!”) This was his first encounter with Yogaswami of Nallur. His search was ended, and he accepted Yogaswami as his guru after many trials and chastisements.§

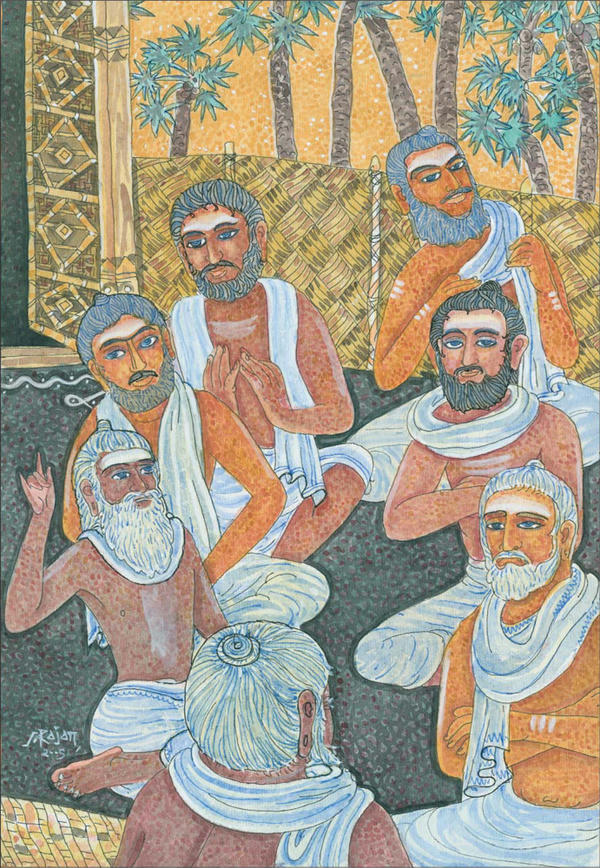

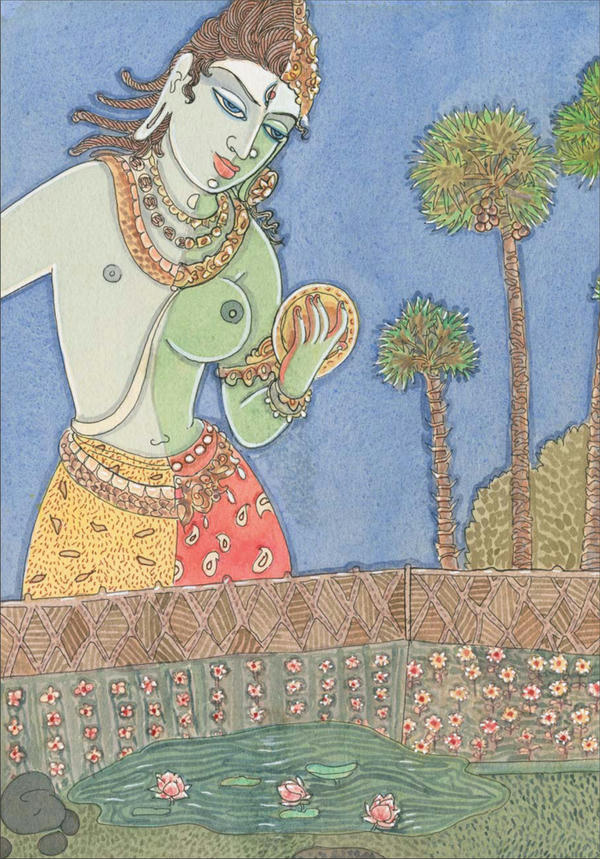

Here we see Yogaswami with his back to us and (left to right) Markanduswami, and five of the six members of the Council of Cubs (the Kutti Kuttam): a Briton (Yanaikutti), a Tamil from Colombo (Pandrikutti), a Sinhalese (Pulikutti), an Australian (Narikutti), and a German (Naikutti).

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •§

One of the great sayings of Yogaswami’s guru, Chellappaswami, emphasizes the same idea. He said, “Naam ariyom,” which translates as, “We do not know.” Satguru Sivaya Subramuniyaswami, Yogaswami’s successor, would later express the same idea in this aphorism: “The intellect strengthened with opinionated knowledge is the only barrier to the superconscious.” He went on to explain that “a mystic generally does not talk very much, for his intuition works through reason, but does not use the processes of reason. Any intuitive breakthrough will be quite reasonable, but it does not use the processes of reason. Reason takes time. Superconsciousness acts in the now. All superconscious knowing comes in a flash, out of the nowhere. Intuition is more direct than reason, and far more accurate.” One day Yogaswami exulted: §

I see God everywhere. I worship everywhere. All are God! I can say that because I don’t know. He who does not know, knows all. If you don’t know, you are pure. Not knowing is purity. Not knowing is knowing. Then you are humble. If you know, then you are not pure. People will say they know and tell you this and that. They don’t know. Nobody knows. You don’t want to know. I don’t know. Why do you want to know? Just be as you are. You don’t want to know. Let God act through you. Give up this “I want to know.” Let God speak. This idea of knowing must be surrendered. Think, think, think. Then you will come to “I do not know.” I don’t know. You don’t know. Nobody knows. It is so. Who knows? If I can say, “I know nothing,” then I am God. §

“Stop reading books,” he told one disciple. “The greatest book is within you. That is the only book you should read. The others are just trash. Open the book that’s within you and start reading it. Be very quiet, and it will come to you.” Seekers were constantly making the spiritual path out to be arduous, convoluted and beyond their capacity, but Yogaswami repeatedly assured them that it was really not that way.§

So simple is the path, yet you make it hard by holding onto the idea that you are you, and I am I. We are one. We look at the sun and feel its rays. The same sun, the same rays, the same nerves doing the feeling. That also happens when we look within. We feel the darshan of the Lord of the Universe, Siva without attributes. The same darshan is felt by you and me alike. Not your Siva or my Siva; Siva is all. We must burn desire and let the ego melt in the knowing that Siva is all; all is Siva. There are millions of devas to help you. You need only implore them and keep yourself steady through sadhana. Then you will come to see all as one and will taste the divine nectar. §

Chellathurai Swami summarized Yogaswami’s approach as follows: §

Spirituality is constant awareness of God or one’s own Self. The sahaja state is one in which one is ever conscious of one’s Self without any effort whatsoever. But to achieve this state, mighty efforts have to be made. Yogar Swamigal taught that this could be done by trying to remember God in all one’s actions. He exhorted everyone to do everything as Sivathondu, which he knew would take one to the state where awareness comes about effortlessly. This, it is said, is the summit of spiritual experiences. To earnest seekers Yoga Swamigal has said, “Practice is greater than preaching,” and “Let your Greater Self guide you;” for he knew that sadhana, or practice, with the Greater Self as guide would take them to the stage in which one truly feels that “Everything emerges from that great silence,” and “everything is the perfection of that great silence.” And these are the words which greet one as one climbs the steps leading to the Meditation Hall in the Sivathondan Nilayam in Jaffna.§

Meditation on Siva

Thus, the gurus of the Kailasa Parampara emphasize that in order to realize God, we must go beyond the limitations of the intellect and its concepts. To guide seekers on the path to this experience, Yogaswami stressed the importance of meditation and formulated a key teaching, or mahavakya: “Tannai ari,” “Know thyself.” This was a second dominant theme of his teachings. He proclaimed, “You must know the Self by the self. Concentration of mind is required for this…. You lack nothing. The only thing you lack is that you do not know who you are.… You must know yourself by yourself. There is nothing else to be known.” Markanduswami, a close devotee of Yogaswami, would later tell visitors to his hut: §

Yogaswami didn’t give us a hundred-odd works to do. Only one: realize the Self yourself, or know thy Self, or find out who you are. What, exactly, does it mean to know thy Self? Yogaswami explained beautifully in one of his published letters: “You are not the body; you are not the mind, nor the intellect, nor the will. You are the atma. The atma is eternal. This is the conclusion at which great souls have arrived from their experience. Let this truth become well impressed on your mind.” §

Knowing that most people are trepidatious about meditating deeply, diving into their deepest Self, Yogaswami gave assurance that inner and outer life are compatible. He counseled, “Leave your relations downstairs, your will, your intellect, your senses. Leave the fellows and go upstairs by yourself and find out who you are. Then you can go downstairs and be with the fellows.” §

One disciple was struggling to understand things Swami said to him. He went from one person to another for interpretations of the guru’s advice. Swami heard of this happening and told him, “Stop running around from place to place like a lamb. Sit down and go within yourself. Meditate. Then roar like a lion.” §

The American Brahmin

Yogaswami met few Americans in his life, but one was soon to come to his humble hut. In 1947, 20-year-old Robert Hansen, traveling with a classical dance troupe calling itself the American-Asian Cultural Mission, disembarked on Ceylon. During his initial months on the island, Hansen gave dozens of dance performances. Here he learned the ancient, healing Manipuri dance and revived a type of dance indigenous to the area around Kandy—a colorful, bold and intricate art form. But the accomplished artiste had traveled to Ceylon to meet his guru and realize the Self. §

Soon he began to encounter saints and sages, adepts of various yogic disciplines, masters of using the third eye, the science of tuning the nerve currents of the body, Hindu mysticism, controlling the forces of the material world and meditation. Each catalyst came to him at just the right moment. Robert felt that each of these meetings was auspicious. In each interchange he felt the pull of his guru. Every adept he met gave what he had to give. He obediently performed what he was told until he felt a release from that catalyst. Then the next teacher, the next swami, the next mufti, would come to open to him another realm of superconsciousness. As this was happening, Yogaswami kept himself veiled, always working through another person. §

Robert had gone to the jungle caves of Jailani and fasted there until he realized the Self. He was continuing to follow a disciplined sadhana. In early 1949, the young brahmin from America, as he was called, met C. Kandiah Chettiar, the Hindu adept who would introduce him to Yogaswami. Kandiah lived in Alaveddy, a village not far from Jaffna town; he had been with Yogaswami for decades and knew him well. They had frequently talked in the streets and shops of Jaffna, and sat together many times in the ashram home of Chellachi Ammaiyar.§

After spending several weeks together in Colombo, Chettiar invited the young man to travel with him to Jaffna. There, Robert stayed with Kandiah at his family home. The American brahmin was quietly eager to meet Jaffna’s legendary “Old Beggar.” Finally, the meeting was arranged. §

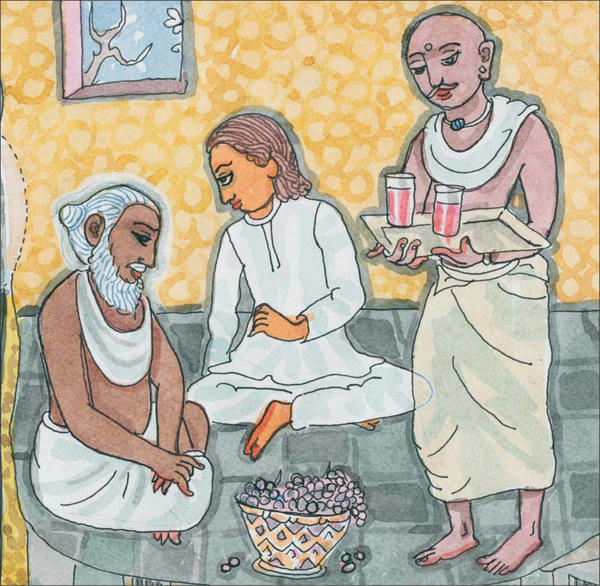

When the 22-year-old American seeker finally met Yogaswami, they were, as the Jaffna saying goes, “Like milk poured into milk.” They had deep philosophical discussions, and Yogaswami asked for fresh grape juice to be squeezed for his visitor.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •§

Siva Yogaswami received the American seeker in his hermitage several times, spoke with him about yoga and things philosophical, gave him a Hindu name, Subramuniya, along with inner instructions, and initiated him with a powerful slap on the back, saying, “This will be heard in America!” When Kandiah heard about the slap on the back, he knew what had occurred. He remarked to close friends, “Now it is finished. Swami has performed the coronation.” The last time Subramuniya approached the hut, Yogaswami yelled out, “Go away. I am not at home.” Yogaswami mentioned his American disciple only a few times thereafter. §

In 1956, when Subramuniya had a climactic mystical experience in Denver, Colorado, Yogaswami said to Kandiah Chettiar’s son Vinayagamoorthy, “Hansen is dead. Hansen is dead.” Everyone felt sad until they received a letter from Subramuniya, sharing that he had begun his teaching work in the West. Hearing that, the Jaffna Saivites understood what Yogaswami had meant. It was the same statement Chellappaswami had made about Yogaswami years earlier.§

Later someone asked Yogaswami if he had left a guru. He replied, “Subramuniya is in America.” Another time he said, “Oh, I have a man in America.” One day Swami was giving some instructions to Vinayagamoorthy, going on about what he should do with his life. Vinayagamoorthy reminded him that he was taking care of Subramuniya’s ashram in Alaveddy, and Yogaswami answered, “Oh, that friend of your father.” But he later remarked to Vinayagamoorthy in an off-handed way, “So, you are helping us build the bridge.” Subramuniya would later relate that “Yogaswami instructed me to build a bridge between East and West.” It was a phrase Subramuniya would frequently reference, and a goal he never forgot. §

During this period, Yogaswami urged people to build bridges to the West. He sent some to England and America to meet his close devotees. He told those going of the importance of their mission, and gave details on what they should say in bringing Saivism to various Western countries. He often talked about the spiritual power that would arise in America and envisioned the day when he would be known there.§

The Council of Cubs

In the late 1950s a group of seekers, one from Ceylon and five from around the world, gathered around the gray-haired master. Haro Hara Amma, a mystic Muruga bhakta who lived on a tea estate near Adam’s Peak, gave each a special name of a young animal, and so the group was also referred to as the kutti kuttam, “council of cubs.” All were addressed as swami, though most were not initiated. They were a wild and diverse, free-thinking bunch, and the only thing they agreed on was that they were all disciples of Yogaswami. In 1956 these six men went to Kataragama to do kavadi, presumably with Yogaswami’s blessings.§

They were: Gauribala Swami (born Peter Joachim Schoenfeldt in Germany in 1907), known as Naikutti (Puppy); Sam Wickramasinghe, a Sinhalese Buddhist, of Ceylon, known as Pulikutti (Tiger Cub); Barry Windsor of Australia, known as Shankarappillai Swami or Narikutti (Young Fox); Mr. Balasingham of Colombo, Ceylon, known as Mudaliar Swami or Pandrikutti (Piglet); James Herwald Ramsbotham of England, the 2nd Viscount Soulbury (whose father was Britain’s last Governor General of Ceylon), known as Sanda Swami or Yanaikutti (Elephant Cub); and Adrian Snodgrass of the United States, known as Punaikutti (Kitten). The elder of the group, Gauribala Swami (popularly known as German Swami) was the only formally initiated sannyasin. He received that initiation in the Giri Dashanami order in North India prior to meeting Yogaswami.§

During the annual temple festival at Nallur, Yogaswami could be found seated with his Council of Cubs in the chariot house where his satguru had lived and ruled. They were a motley crew, but they all understood the paramount importance of the guru and obeyed his every command. Swami made stern demands on them at times, swore and sent them running, but was also nurturing, giving each the subtle push needed to overcome the limitations of ego and proceed in his religious life, for each was intently striving for higher states of being. §

Sam (Pulikutti) recalls, “He once said to me, ‘The greatest scripture one can learn from is life. Learn from the book of life. Watch yourself and your reactions to externals. Don’t suppress anything—go into every situation that strikes your path and watch mindfully, in joy or in sorrow, in anger or in love, then one day, quite suddenly, unexpectedly, the watcher who is watching all this and getting involved in all this will be seen!’” §

T. Sivayogapathy shared some insight into the life of Sandaswami, who is considered one of Yogaswami’s foremost brahmachari disciples. §

German Swami is said to have lived in Jaffna from the early 1940s, predominantly in the Chelvasannathy Murugan temple at the northern tip of the island. He met Yogaswami in 1947, and introduced Sandaswami to Yogaswami in 1953. Three years later, Yogaswami initiated Sandaswami and assigned him to reside, meditate and serve at the KKS Road Sivathondan Nilayam, Jaffna. Yogaswami instructed Chellathurai, the Nilayam manager, to “be alert and not to allow German Swami to influence Sandaswami in a wrong direction.” Devotees remember the English seeker as a serious, dedicated brahmachari who was often seen avidly studying books related to Saiva philosophy. Later, after Yogaswami’s mahasamadhi, he spent twelve years in Batticaloa, managing the Sivathondan Nilayam in Chenkaladi. In his later years, he returned to Jaffna and stayed for a few years with Markanduswami at his humble hermitage and ultimately returned to England and to his noble family. He attained mahasamadhi at the age of 92 on December 13, 2004.§

Solace for All

Thousands and thousands of people approached him over the years, from all walks of life, from all corners of the Earth. Some visited him for purely worldly reasons, others for spiritual blessings, some to test him, some with medical ailments, some for visions of their future, others for blessings on undertakings. In the words of Sri Tikiri Banda Dissanayake, “To all stricken in body or weighed down by sorrow, he had a word of solace and a blessing. Everyone went away refreshed.” Ratna Ma Navaratnam wrote: §

People of all faiths, men and women from different walks of life, seekers from all parts of the globe, east and west, north and south, the rich and poor, old and young thronged to him for succor, for they realized that they were in the presence of a great Master in whom conflicts and contradictions did not exist, and who radiated an abiding inward peace—santam upasantam. §

Swami’s effulgent face, penetrating eyes, the white flowing beard, and the spreading forehead with the gleaming holy ash, his waist cloth of white cotton, and the hair knot on the crown of his regal head, altogether struck awe and majesty in the hearts of those who approached him with infinite reverence and humility. §

S. Nigel Subramaniam Siva treasures this anecdote: §

One day, as usual, my father, Subramaniam, went to see Siva Yogaswami. Yogaswami told to my father, “I have to tell you some news.” My father was very attentive to hear what Swami was going to say. Yogaswami announced, “God Siva really exists, and I have no news other than that.”§

One morning a man came to share his life’s sorrows with Swami, complaining that he had several daughters and could not afford the dowries that would be required to get them married. Now one had received a proposal. Wordless, Yogaswami reached into his veshti (into that hip pocket that is really just the cloth folded in upon itself) and handed the man ten thousand rupees for the dowry. Other fathers he told not to worry, that men would marry their daughters based on their merits. Invariably, it came to be. S. Shanmugasundaram recounts how Swami once called upon other devotees to assist a man with his daughter’s dowry: §

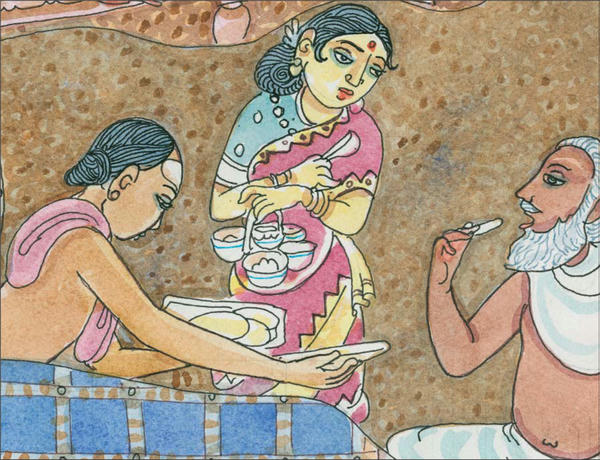

Yogaswami often visited a devotees’ homes without notice, sit in meditation, take a meal, sing a sacred song and, from time to time, spend the night. His closest devotees kept a special room for such a blessed visitation.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •§

Yogaswami’s heart was full of love and compassion for everyone. Whether he smiles at you or scorns you, whether he embraces you or kicks you, every act of his is an act of love and grace. Without any outward show, he would shower so much compassion on all beings. The care and concern he had for those in need was immeasurable. He never disappointed any sincere devotee who approached him with a problem. One fine morning, Yogaswami was seated in his hut with two devotees in front of him. He was chatting on various topics. An old man came there and stood outside the hut. Swami summoned him inside and asked, “How is everything going with you?” Without uttering a word in reply, the man broke down crying and sobbed for two or three minutes. §

Then Swami spoke, “Don’t worry. Siva will show you a way out of your difficulties. You may now go home in peace.” The man left as directed and Swami addressed the two devotees who remained, “He is a good-hearted man. He is experiencing some difficulty in giving his daughter in marriage. She is 26 years old, and a cousin of hers is willing to marry her if the father will at least provide her with the minimum jewelry. Why don’t one of you help him?” Immediately A. Thillyampalam offered to do the needful. Excusing himself, he ran after the man and got his name and address. The next day he went to his house and presented him with a gift of Rs. 5,000. The man was overjoyed. Without any delay, he got all the necessary jewelry made and gave the daughter in marriage.§

Sometimes those who saw the great numbers coming to Swami wondered why he allowed so many, and why he did not refuse to see certain people, such as lawyers who came to him before arguing a case, knowing that just being with Swami for a few moments would help them. He once explained, “I see everyone, and everyone takes from me what they can hold. It is not my job to pick and choose, to say this one come and that one go.” S. Kandiah of Ontario observed that those who came to Swami were of three categories. §

The first were the exclusively spiritual, ascetic type. This was a very small number. Swami kept them aloof of the others, even visiting them instead of them coming to him. The second category were those living a worldly life, with all its enjoyments, but who had a touch of spiritual tendencies. The third were those mainly looking for worldly pleasures, positions, wealth, etc. §

As I began to grow very close with the swami, all feelings of fear and stress gone, I one day asked him why he encouraged the latter hypocritical hangers-on around him. He gave out a hearty laugh that could have been heard a hundred meters away and asked me, “Do I have to make good men good, or bad men good?” In other words, all have a place with him, sinners as well as spiritual aspirants. §

But he did chase some away in no uncertain terms, occasionally using the foulest language that had immediate effect but which devotees could never repeat. And he did refuse to see others. He explained that by chasing away or refusing to see someone, he was also giving darshan. §

Once one of Swami’s oldest and sincerest devotees visited, accompanied by his youngest daughter, who was getting married the next day. They came, of course, for Swami’s blessings. Hearing them at the gate, Swami called out, “Who’s there?” A devotee who was sitting inside went out to see, then reported back who it was. Swami responded, “Who is he?” Everyone knew that Swami knew him well. They also knew why he had come. §

Swami was quiet for a while then said, “Tell him we don’t want to see a stranger now. Tell him we can’t see him now.” A devotee conveyed the message. As soon as the car drove away, Swami sent someone out to see if it had gone. Everyone knew it had gone. They had heard it leave. But Swami wanted someone to check. As soon as that person came back to the hut, Swami started laughing. He laughed uproariously. Then he told those around him, who were deeply puzzled by his behavior, “It was settled long ago. Finished long ago.” No one ever knew why he refused to see this devotee and his daughter, but they all sensed there was some spiritual purpose behind the scene they had witnessed. §

A close devotee, a regular visitor to the hermitage, recounted one occasion when Swami told her to go away. §

Normally for Dipavali, a festival of lights that takes place in October, we buy new clothes for our relations or anyone to whom we want to give. So I bought a nice veshti for Swami. I went to Swami’s place and waited, but he didn’t call me in for a long time. Finally he said, “I don’t want anybody to come in; all of you go away.” I felt so sad, I cried. Then he said, “All right, don’t bring your veshti in, but you can come in.” I felt sad because Swami refused to take the veshti that I brought. He then quoted an example about a king called Janaka who was also a great saint. “Janaka’s guru made him wait for forty days, and he was not perturbed. He just stood there. You, like a fool, you are crying for a little thing.” Then he sent me away. “First obey, and then command,” he used to say.§

Once a man was inspired to open a bookstore, beginning with a collection of used books he had obtained. He wanted Swami to come and bless the store, but every time he saw Swami, the request slipped from his mind. Somehow, in Swami’s presence, it didn’t seem important enough to mention. He arranged to have a small ceremony at an auspicious time to mark the opening. The time of the ceremony arrived, and still he had not invited Swami. Yet, at the exact moment the astrologer had set for the puja to begin, Swami arrived. In time, the shop became the foremost bookstore in Jaffna. The owner considered its success a direct result of Swami’s blessing that day. §

Hundreds of stories are told of Swami’s answers to unspoken questions and fulfillments of impossible-to-know needs. If someone came and had a significant experience with Swami, or received some important help, he would forbid them to talk about it. “Sacred is secret, and secret is sacred,” he admonished. So carefully did people keep that advice, that neighbors both might have visited Swami and not have told each other about it. Many regarded it as amazing that such a secret could be kept in Jaffna—where the breeze itself carries news. §

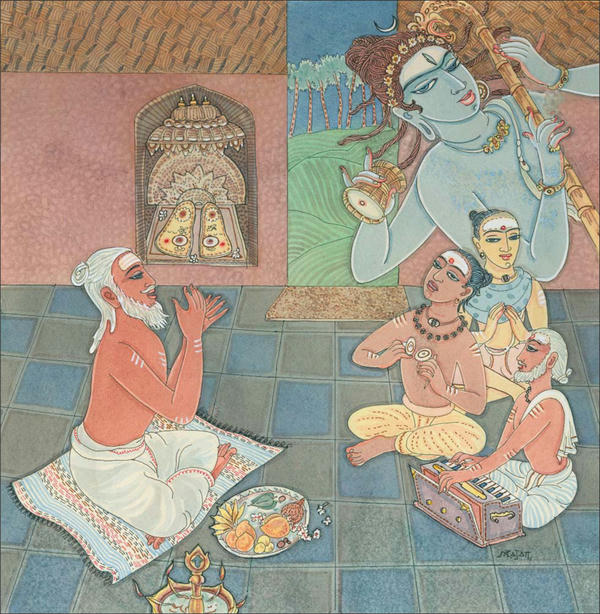

Devotees came to see Swami either early in the morning or in the evening. He would awaken before dawn and meditate in his hut. The devout would come and sit with him. After remaining in silence for some time, Swami might start to sing. He had a rich voice, full and melodious. Once a devotee asked him what a certain song meant, to which he answered, “Oh, I didn’t write that song; it came from within.” He would also sing hymns and scriptures composed by other saints. He would say they also came from within: “I could have retrieved that song from memory, but I did not. It came from within.” §

He might ask a devotee sitting with him to pick up a book and read from it: the Taittiriya Upanishad, a work from the vast Tirumurai, Swami Vivekananda’s writings or some other holy book. §

Whenever people sang for him or read, he would ask them—or even scold them—to read not as if they were reading about some time and place far away and removed from them, but as if they were Siva or Saint Manikkavasagar right at that moment. “That’s the only way to understand these words,” he insisted. Swami challenged each one who approached him. §

The only difference between you and me is that I know who I am. Can I help you find out who you are? I can show you the way and light the path, but you must stand on your own feet and do the work yourself. Everything is within you. You have only to find it and claim it. I can show you the way to go to Keerimalai or the way to Nallur. I know the way. I’ve been there many times. But if you want to go there, you must do the walking. I can’t do the walking for you. It’s the same with the spiritual path. §

Over the years, by his tireless efforts to uplift, inspire and assist each person with whom he came in contact, Swami built up a strong congregation of devotees. Inthumathy Amma writes: §

By staying at the Columbuthurai Ashram and by going to the homes of devotees, Swami attracted a great following. Among those were some who were transformed into serving God by doing service to others, by taking and giving to others. Yet others, true to the words “Whoever thinks of me constantly, they are my good devotees,” became devotees who thought of him constantly. Some entire families—husband, wife, parents, children, uncles and aunties—all became devotees as a group. Some of these families, disregarding the comments of others that they were mad, named their children Sivancheyal, Sivathondan, Yogaranandan, Yogaranban so that they could be constantly reminded of him. Yet others became karma yogis. §

Some renounced and became acolytes, living near Swami. Even one who belonged to the nobility in England renounced everything and became Swami’s devotee. Markandu Swami and other brahmacharis followed Swami’s path of “Know Thyself,” matured and became guiding lights to all the devotees of Siva. Swami’s divine children, through religious knowledge and experience of dharmic conduct, strengthened by the disciplined life and observing the laws of celibacy, followed in his footsteps.§

Some of Siva Yogar Swami’s devotees were in government service. Those people who worked all over the country could not come to the ashram frequently. Hence, Swami went in search of them at their homes. Especially when they were in deep trouble and appealed to him with a broken heart, he would appear before them and bless them with divine grace. He went often to the postmaster at Mabale, and to Mr. Kandasamy’s house, to the cottage of Mr. Veluppillai at Peradeniya, to the home of Dr. Ramanathan who worked at Gampola, and to other places. He also went to Mr. A. Thillyampalam’s house in Ratnapura and to many peoples’ homes in Nawalapitiya. In this way, Swami visited many devotees’ homes all over the island. Those devotees maintained their shrine room with great care as Swami’s own room. When they learned that Swami was at a particular home, they flocked there for his darshan. §

For about twenty years, he went once a month to the Hill Country, to Colombo, to Trincomalee, to Batticaloa and other places and in this way brought up his devotees. All the homes that Swami visited began to flourish like temples. Then, in 1942, at age 70, he decreed, “There is no more going to outside places. Those who so desire can come here.” §

A devotee recounted the following anecdotes.§

One evening, when about fifteen people were gathered in the hut, Swami asked all of us how many were there. Nobody said anything. Then Swami said, “There is only one person.”§

Swami often inquired, “If you are told you must not speak the truth, you must tell a lie, then what should you do?” One day Sandaswami was there, and Swami asked him this question. Immediately Sandaswami put his finger to his lips. He didn’t speak. Later Swami told us, “He is a great man. So many people in Jaffna gave me all sorts of explanations; he just showed it in silence.”§

One morning at about 5:30 or so, I went to Swami. As usual, he was sweeping the compound. He used to sweep the whole place every morning, heaping the dust on one side, the cow dung on the other. Then he stopped and shouted deliberately, “Who is there? Who has come?” Then he told me, “You know, all this time I was a lavatory coolie; now I am a swami.” Then he went into the hut, took a small copper vessel and made a kumbha by filling it with water and placing a tumbler and some flowers in it. I think he meant he was purifying people’s hearts. He would say, “There should be someone to turn people in the right path. Christ did that, Buddha did that. I am also doing that.”§

One day I brought some tea to Swami in his hut when Sandaswami was there. He offered his cup of tea to Sandaswami, so I said, “Wait, Swami, I’ll bring another cup for him.” Swami responded, “Mind your own business; I know what to do,” and gave the tea to Sandaswami.§

Yogaswami always wanted people to work. He emphasized work. “Work till you shed blood,” he once said after sweeping. “Do your work. Do your karma. Don’t expect any return. That is yoga. That is sannyasa.” In other words, don’t attach yourself to things. §

Once when we were all at Swami’s place eating from plantain leaves, when everyone had finished dinner, a lady doctor who was there wanted to take Swami’s leaf to throw it away. Swami said, “I can do my work. You do your work.” §

Swami opened the path of service to his devotees. “Work, work, work; serve, serve, serve.” He always had a project going, something that seemed like more than anyone or any group of people could accomplish. And he demanded it be done to perfection, never allowing them to settle for second-rate performances. If it was a drama for a Hindu festival, he would boldly offer advice about the production. Swami might even act out parts of the pageant like a director, rehearsing scenes, stretching each participant a little beyond what he thought was his capacity. “You are more than you think you are,” he would chide. Each one discovered new strength in fulfilling his expectations. A devotee recalls:§

If you were organizing a feeding for a thousand people at Nallur Temple, he made sure you had everything planned well so the event would go smoothly. He wanted to know precisely what curries you planned to serve, and might suggest substitutes or cutting back on the quantity. “Three curries is enough,” he would direct. §

If you and other devotees were rebuilding a temple that had fallen into disrepair, he would get involved, making sure you rebuilt it properly and had the necessary ceremonies conducted for its reopening. He would even inquire if you had provided an adequate endowment to keep the temple functioning well into the future. §

If a devotee had accomplished something and came to Swami for praise, he would strip him down to size quickly. Sometimes he would ignore a devotee’s achievement entirely and quickly guide his attention to another project that needed work. Or he would scold, “So, you think you have put on a good feeding? Was it you who put life into the food? Into those who cooked the curries? Who created hunger? Who discovered the way to satisfy it? My child, you must not think you have done anything. It is all the work of the Lord. When you know that, then you will know you have done nothing.” §

“Be like water on a lotus leaf,” he urged. In other words, don’t get attached; be free to move here and there with the feeling that nothing is happening. One time a devotee close to Swami had what he considered an extraordinary spiritual experience. He had encountered, in meditation, dimensions of consciousness that were remarkably new to him. In the street the next morning, Swami asked him what had happened. Without thinking, he blurted, “Nothing, Swami.” “That’s right,” Swami affirmed. “Nothing happened.” §

Yogaswami knew exactly what each one who came to him wanted. People rarely spoke in his presence. It was against guru protocol unless he initiated the discussion, and most often they simply found themselves unable to ask questions. If they did, he would say, “Your ignorance is speaking! Send it home!” Usually he cleared up questions before they were voiced. One devotee thought, “Krishna showed Arjuna his divine form. I would like to ask Swami to show me his divine and resplendent self. How can I ask so that he will not scold me?” Right then Swami said, §

Some people wonder if I can show them my effulgent being, as Krishna showed His to Arjuna. That is easy. It will happen to each person when the time is right. But you must have no desires lurking in the corners of your mind. You must purify yourself of all desire. Sing hymns, chant “Aum Namasivaya, Sivayanama Aum,” wear holy ash and practice any sadhanas that help you quiet desire. If you find desire, make your mind a funeral pyre and burn that desire. Burn it! Sit in meditation and watch it burn. Feel the flames. Then get up and wash and apply holy ash. And know that the ash is the ash of your desire. §

Blessed Scoldings

Yogaswami closely watched how people revered him. One of his greatest teachings was to have devotees recognize within themselves what he represented to them. A person might worship him with the feeling that “I am so small and powerless and you are so great and powerful, let me enter your good graces so all the bad things I’ve put into motion, and that I’m sure are going to react back on me, just won’t happen.” Anyone coming to Yogaswami with such attitudes might be scolded and sent abruptly on his way. “Why are you worshiping me? I have two eyes, two ears, a mouth and a nose, just like you. Go do your own work. Stand on your own feet!” §

Yogaswami was a great scolder. His scolding was more penetrating than fire. Years after Swami’s mahasamadhi, his German disciple, Gauribala Swami, was told by his own devotees that he was a bit gruff and forceful. “Ha!” he chided, “I’m gruff? You couldn’t stand for thirty seconds in front of my guru.” Many are the stories of Swami’s profane language, which he reserved for rare moments with devotees and as a useful way to ward off base strangers. §

One man was constantly around offering to serve him, worshiping him with what seemed like true devotion. One day Yogaswami harshly lit into him, speaking the filthiest Tamil there was—language that could make a sailor blush. He kept at the man for over an hour for being afraid, for fearing what might happen to him, what he might have to go through. All the horrible things he had imagined, and some he had not, Yogaswami hit on, naming every one and scolding all the while. It was terrible. He finished, “If you think I’m going to protect you from any of these things, you’re wrong. I don’t even see them as real. You give them power; you get rid of them. There is nothing to fear, so stand on your own two feet and stop bothering me with your worries and fears, and get rid of them before you come to see me again.” §

In Homage to Yogaswami, Sam Wickramasinghe offered a mystical explanation for Yogaswami’s responses to those who came before him.§

A liberated mind has the advantage of being a mirror in which a non-liberated mind can see itself as it truly is. If Yogaswami seemed to lack an unchanging personality, it was presumably because his “personality” temporarily acquired the characteristics of his visitors. Not surprisingly, therefore, proud persons invariably found Yogaswami behaving arrogantly towards them. To those who were haunted by fears, Yogaswami’s manner seemed timid. §

A South Indian sannyasin recited a stanza from the Bhagavad Gita to Yogaswami. Thereupon, Yogaswami repeated the stanza with alterations and clever puns on certain words so that the sacred lines acquired an erotic significance. Yogaswami could not help doing that, for he was merely reacting to the hidden sexual imagery in the unconscious mind of that recluse. Consequently, this ascetic, like many other of Yogaswami’s visitors, was not only irritated but embarrassed. §

In a sense, Yogaswami was a Zen master who awakened people from their psychological slumber by shocking them without deliberately wishing to do so. The people of Jaffna regarded Yogaswami with a curious mixture of veneration, affection and fear. Some of his ardent admirers seemed more to fear than love him. To be received by Yogaswami, it was necessary to approach him without any ulterior motive whatsoever. §

Yogaswami chased away most of his visitors. Many persons unfortunately regarded Yogaswami as a mere fortune-teller with the gift of making accurate forecasts. At one time Yogaswami had a stream of visitors every day from dawn to dusk. They came to him with various personal and other problems. Those who were privileged enough to be received by him usually regarded themselves doubly blessed. Some of those who were rebuked by Yogaswami regarded themselves spiritually chastised.§

Seeing through the facades people presented to him, Yogaswami would rudely expose what was really on their minds. Mr. Nagendran shared this account. §

It was the 1940s. I had just passed the Advocates Final Examination and was due to take my oaths at the Bar. I came back to Jaffna to spend a few weeks. Mr. Veerasingam, the retired principal of Manipay Hindu College, came to the house of my grand uncle Sellamuttu, where I was staying, and asked me to accompany him to Columbuthurai to see Yogar. §

Before we reached Swami’s hut, Mr. Veerasingam told me, “On the way to see a great man, we should not go with empty hands. We should take offerings.” He stopped the car and purchased plantains, apples and other fruits, and had them wrapped up. As we reached the hut that evening, Yogar was seated on a mat covering a thin mattress on the floor. §

Mr. Weeram, the Commissioner of Cooperative Development, my father’s senior in the department, and other distinguished elders were seated in front of Yogar. As soon as he saw us enter his hut, Yogar said, “God is one, though sages call Him by various names.” This phrase hit me, as these were the words painted on the wall of the shrine to Ramakrishna at the Mission Hall at Wellawatte, which I used to visit at that time. Has he, I wondered, divined my visits to the Ramakrishna Mission? §

As was his usual practice, Yogar unwrapped the parcel which Mr. Veerasingam gave him and began distributing the fruits to the elders in front of him. Seated at the rear, I noted the number of fruits he gave each elder, wondering whether he would give me, a person not of the same status as the elders, the same number of fruits. While Yogar was handing the fruits to me, he remarked, “Everybody here gets the same number. See, even one of the fruits I am to give you has fallen because you had doubts.” Yogar had read my mind. I was humbled.§

In 1953 Swami Sivananda of the Divine Life Society sent a young sannyasin, Swami Satchidananda, to Ceylon to open a small yoga center in the hill station of Kandy. Charismatic and humorous, the dark-haired swami from South India drew crowds for his hatha yoga classes. One day he made his way to Columbuthurai for the blessings of Yogaswami. He described the meeting: “I entered the hut and prostrated. Immediately Yogaswami asked me, ‘How many people do you have standing on their heads today, Swami?’” Satchidananda inferred that Yogaswami was encouraging him to use his considerable gifts for more than teaching the physical yogas to common crowds. Years later, Swami Satchidananda ascended to fame when he gave a talk at the Woodstock festival in New York, and later founded the Integral Yoga Institute in the United States. §

Siva Yogaswami’s closest devotees longed for these scoldings and regarded them as a benediction. One day Yogaswami went to the house of a devotee named Kandan, taking another devotee, Arumugam, with him. Kandan was waiting in the yard when Swami arrived. Suddenly, Swami started pummeling him on the shoulders with both fists with all his might. Kandan stood still for it. When Swami was finished, Arumugam, somewhat aghast at the events, noticed that Kandan looked more blissful than abused. Kandan, sensing his friend’s puzzlement, sighed and confided, “I have been waiting a whole year for that blessing. Every three or four years I need a good, strong thrashing from Swami; then I’m fine.” §

Singing the Tamil devotional hymns to Lord Siva is a strong part of Sri Lankan spiritual culture to this day. Yogaswami had devotees loudly and passionately sing Devarams and Natchintanai whenever they visited his hut.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •§

He Who Knew All

When someone came to worship Yogaswami to change the part of himself that Swami revealed for him, he was encouraged, given what he desired, and sent on his way. Such devotees did not have to say anything. He would just start answering their questions or telling them their next step. He also knew what people were thinking and what they wanted him to do for them. Who was coming and when they were coming and why they were coming were known beforehand. Sometimes he would say, “We must go now. So-and-so will be here in fifteen minutes and he mustn’t find us here.” Or, “Put a mat there and prepare some tea. So-and-so will be here within the hour and we must have everything ready for him.” §

Many people came with family problems, money worries, or other difficulties. Sometimes he would scold them and send them off to solve their own problems: “You knew how to get yourself into that mess, so you must know how to get yourself out.” Sometimes he would send them to the temple to do a special puja. “Do an abhishekam at the Ganesha temple near here. Then the answer to your problem will come.” Sometimes he would ask another devotee to help. He would say to a third party, “Go and get five hundred rupees from so-and-so and give it to this man. His wife is sick and he needs help.” Money would always come. §

Hilda Charlton, who became a strong Muruga bhakta and helped establish the Bowne Street Ganesha Temple in Flushing, New York, found that her money problems vanished after her visits to Yogaswami. She wrote: §

He was exactly what you would think a yogi would look like—soft gray hair, gray beard, elderly, wonderful. When I used to go to see him, I would travel all night on an old train to Jaffna, where all the warfare in Ceylon is going on now. This one time I had brought some camphor. The day before, my friend had taken somebody there who wanted to know about a lot of worldly things. When this person went in there, the yogi asked him, “What have you got behind your back?” The man said, “Camphor,” and the yogi said, “Burn it on your own tongue.”§

Yogis could be tough, kids. Then he said to my friend, “Why do you bring people of that caliber here?” I came in the next day. I had some camphor behind my back. I had just heard this story. He asked, “What have you got behind your back?” I said, “Camphor,” and he said, “Come right in, come right in.” See? §

Every time I went there, he would say, “How much money do you have?” It was just like Yogananda with the food. I would think, “What kind of a person is this?” I would give no answer, and he would know I had no money. He would ask, “What is your salary?” Well, I didn’t have any salary. So one day I was honest with him and said, “I don’t have any money.” He said, “Oh.” He had a boy take a book and read, and as the boy read, the yogi sat there moving his hand a certain way. §

The boy read, “There is an upper jaw and a lower jaw and the tongue is the conjunction. The tongue makes the sound, and the sound is prosperity,” and the yogi asked, “What is that word? You mispronounced it. How do you spell prosperity?” The boy spelled it out. All the while the yogi was moving his hand, doing something. You understand? I never had money trouble after that. §

Hilda Charlton wrote of another visit she made to see Swami: §

The other day at 4am we went while it was still dark on a pilgrimage to see Yogaswami. As we sat listening to him in the flickering coconut lamp light, he sounded just like Mary Ellen. It could have been her talking. He was so simple, sweet, childlike, and his message was hers: that everyone is pure and perfect, only they don’t know it. To love is the answer to all things. I came away with a spiritual intensification. It was really fine. He accepted nothing. He said, “I take nothing and I give nothing.” But of course he gives a great deal. Though he sees few people, he talked to us for an hour. §

Whatever was brought to Swami during the day he distributed by the time everyone left at night. He would give out the fruit and flowers offered to him, then start dismissing people. No one left his presence without his bidding, and no one stayed after being asked to go. Those with needs for which Swami could be of assistance were usually the last to leave. Then he might hand them money, food or cloth he had been given. §

He did not always receive what was offered. He explained, “We never accept things from people who are trying to influence us or work their way up in the world or trying to buy a good conscience.” He would leave such a gift untouched, or even throw it aside. Sometimes he even refused things offered by his closest devotees. “No orders,” he would say. §

One time a family of devotees who had stumbled on good fortune, which they attributed to Swami, arrived bearing a tray of gold sovereigns. There must have been a hundred coins in all. Swami said, “We cannot accept this. Take the coins back and find a good use for them. I’ll just take a few.” He took three or four. At the end of the evening, those coins were gone. A few fortunate visitors must have received them concealed in a handful of flowers or sweets.§

There was a widespread belief that Yogaswami was partial toward wealthy and famous people who occupied high positions in public life or politics. S. Shanmugasundaram recorded Swami’s views on this criticism.§

One day a young devotee seated in the hut drew enough courage and posed the following question: “Swami, there is a misunderstanding among our people that you are friendly with only rich people, that you visit only their homes and that you do not care about the poor. Is there any truth in this?” §

Swami smiled and replied: “People who have not been exposed to wealth, position and high life are generally good people. They are not a source of danger to the world. It is the rich and the high-society people who are full of bad ways and have qualities like selfishness, envy, greed, bad moral character, etc. If this latter category of people can be changed to live a better type of life, they can become more useful to their people and to the world. Fortunately, it is that class of people who come to me for the most part. What harm is there in my trying to improve their lot and through them improve the lives of hundreds of others?” Not only the young man who posed the question, but all the devotees present before Swami, were happy at his answer. §

Many rich and famous people, in order to enhance their reputation further in society, try to strike a friendship with swamis, politicians, business magnates and popular film stars. There were a number of people who approached Yogaswami with such motives, but many of them found they could not withstand Swami’s shouts and scoldings. However, a few reformed themselves, became good Hindus and lived useful lives after their association with Yogaswami. Many of them became great Sivathondars, changed to a virtuous life, gave plentifully to those in need, brought religion into their lives and continued to be ardent devotees of Swami. §

One of Lord Siva’s traditional forms is Ardhanarishvara, half man and half woman. In this form Saivites of Ceylon worship the unity of Siva and Shakti. Yogaswami sang, “O He who became both male and female, devotees offer their praise. O He who is heavenly. O He who has delivered and elaborated the meaning of scripture. O He who is She with the narrow waist on His left!”

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •§

It was Siva Yogaswami’s dictum that “Man is one and God is One.” Therefore, he loved and respected all beings. Swami used to say that if an animal is cruel, he will not do much harm to the world, because people know it is cruel and they can safeguard themselves. But if a man is cruel, he is capable of destroying a whole community. Therefore, if he came across people who were not true to themselves, who did not live virtuous lives, who paid obeisance to him only for selfish purposes, he scolded them properly, shouted at them and threw them out of his presence. This, too, formed part of Swami’s grace, because there are many devotees who were able to reform themselves through this kind of treatment. However, due to this method of dispensing grace, many people feared to seek Swami’s darshan.§

Of course, not all who came to the ashram were of the educated and influential class, as S. Shanmugasundaram notes in this story:§

One day, at about 12 noon, when the sun was unbearably hot, an old woman came into the hut, panting and perspiring. She appeared to have come a long distance, and she was carrying a large jak fruit, since it was known this was among his favored foods. She unloaded the burden in front of the Swami and sat down with a sigh of happy relief. Swami watched all this and addressed the woman thus: “Look here, are you mad? Why did you walk all this distance in this hot sun carrying this huge jak?” §

The woman waited for two minutes and retorted: “It is I who carried it all the way for you. It was my pleasure; why do you reprimand me for that? I am not asking for anything in return from you. I wanted to bring it to you, and I have brought it. Now let me rest for awhile and get back home. You keep quiet.” Thoroughly surprised at the woman’s innocent admonishing, Swami told her, “You can have a fine rest and also a life of peace and joy.” He had her served with a cup of coffee and told his devotees, “With one sentence she has shut my mouth. It was my fault to have blamed her.” He then gave her an orange and sent her home.§