Chapter Fourteen

Yogaswami, Peerless Master

Time after time, Siva Yogaswami told his devotees that all that is needed is the darshan of the satguru, the being who knows and is That. “Chellappaswami was a mother and father and guru, everything to me,’’ Yogaswami sang in one song after another. In Hinduism it is traditional to worship the feet of the guru, which are represented by his sacred sandals, called shri paduka in Sanskrit and tiruvadi in Tamil. Why? Some say that the power that resides in the guru’s nervous system flows out through his hands and feet, and thus the feet are a way to connect with that pure power. Others see it more symbolically, taking the feet as the lowest part of the guru’s body, and seeking to be worthy to touch even that most humble part of divinity. In this sense it is a surrender to the divine they themselves seek to one day become. §

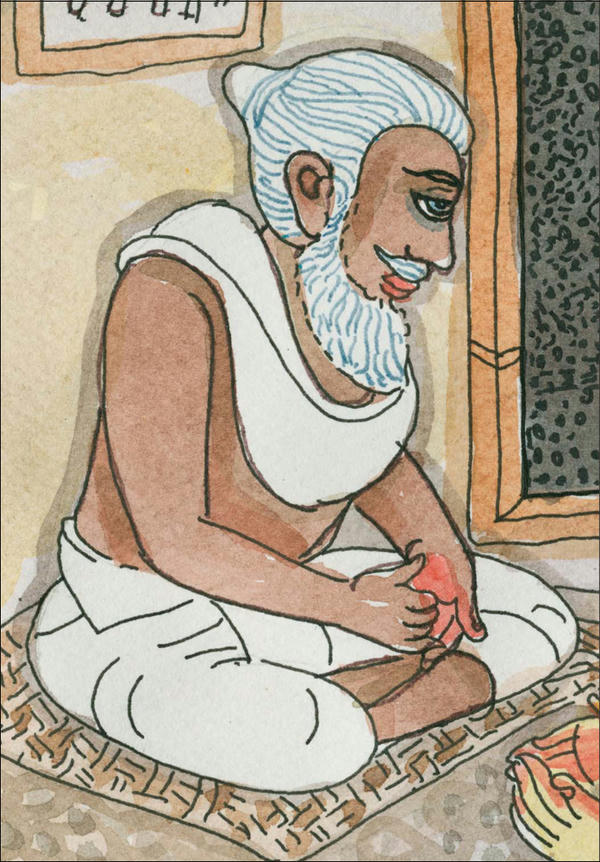

Yogaswami had a pair of his guru’s wooden sandals enshrined behind a curtain in his single-room hermitage. To these, his most sacred possession, he offered worship each morning. His daily routine was to awaken early, bathe, pluck a few flowers and perform arati, passing burning camphor before them on a raised pedestal. These still remain today. It was his only personal worship, other than visiting certain temples. The sandals also reminded all who visited Yogaswami that, indeed, he too had a guru who had led him to the goal. §

He was typically dressed in a white veshti that was forever and magically spotless, despite the dusty Jaffna roads. He often threw a white cloth of hand-woven cotton over his shoulders, his feet clad in simple brown sandals, worn from his incessant walks but well kept. A few of his personal items remain today. A stainless steel water cup and shower towel with colored stripes are kept on his altar at Kauai’s Hindu Monastery, and the family of Ratna Ma Navaratnam, a close devotee, cares for his black umbrella. Dr. S. Ramanathan gave the following insights into Swami’s daily habits.§

Yogaswami was a mysterious medley: a solitary mystic who drew crowds to his feet, a loving guru who could speak harshly, a man with little education who wrote literately of the highest philosophy, a yogi who loved to drive through the villages, a simple man who confounded everyone who met him.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •§

Swami kept his body clean. He would not bathe for long hours, but always washed himself. A soft, sweet scent would always emanate from him. Early morning he would take a cup of tea with milk. At noon he would eat rice. The way he prepared rice was very clean, but he never bothered about taste. By observing for many days the way he ate the rice, I deduced that he ate as a matter of habit and that it was not necessary for him to eat. When he ate, I always thought, “Salutations unto him who never ate and who never slept.” §

He would take tea in the evenings. If he was hungry, he would eat stringhoppers or bread at night. Swami did not allow others to wash his feet, let alone pour water over them. He would not allow others to remove the banana leaf on which he ate. He would dispose of it himself. He never liked a mattress on his bed. He did not like others to honor him as a swami. He would often say, “Do not make me a swami.”§

S. Ampikaipaakan provides the following details.§

Swamigal was very particular in taking care of his body. He did not want to trouble others by becoming sick. He was careful in the food he ate. As he preached, he ate moderately, saying, “Even if God gives you food, do not eat when you are not hungry.” Some days he did not eat all day, and sometimes he ate only a bun. Before he ate, he washed his hands, legs and face and applied holy ash to his forehead and body. §

One day Swamigal saw a brahmin teacher in a restaurant sitting to eat after just washing his fingers. He admonished him, “You are a brahmin; you should know that one should wash one’s face, legs and apply holy ash before eating. Since you are a teacher, you should be an example to your students.” §

Good Thoughts; Inner Orders

Siva Yogaswami taught each devotee the proper manner of worship, that would eventually empower him to see the divine within himself. And by talking or singing of his own guru, Chellappaswami, he also taught about worshiping the guru. §

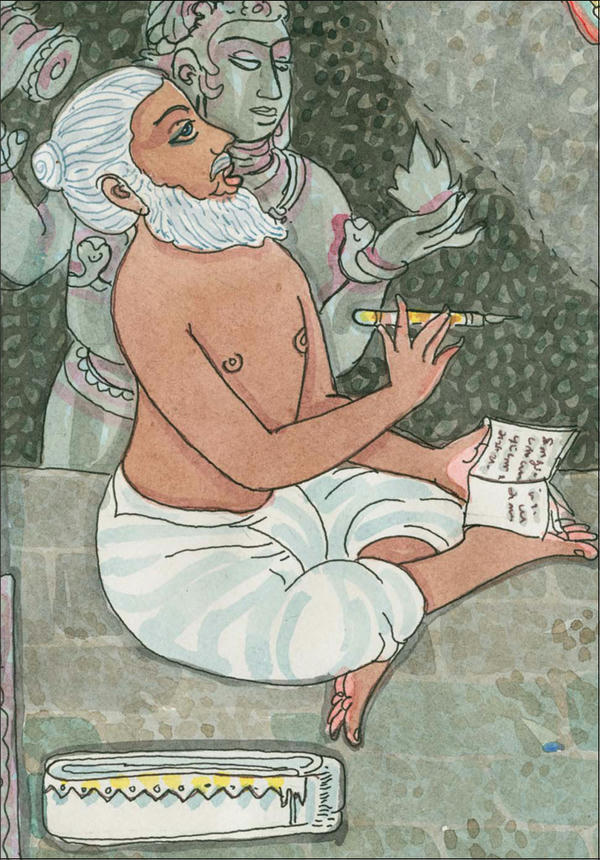

Often he would sing spontaneously. Sometimes he would arrive at a devotee’s house with a song written down that had come to him from within. Invariably someone would write down what he was singing and hand the song around. Eventually a selection of songs and writings were published in a book called Natchintanai (a Tamil word meaning “good thoughts”) in 1959, with a second, expanded edition in 1962. §

The legacy of enlightened souls often includes literary treasures and insights. Yogaswami left the world his Natchintanai, hundreds of spiritual songs.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •§

Swami’s teachings explore the mysteries of yoga, disclose the divine experiences on the path and praise Chellappaswami and the Mahadevas, especially the supreme Lord, Siva—avoiding the intricate complexities of the Tamil language, but instead using charmingly simple vocabulary and phrasing. In all, Swami’s compositions consist of 385 Natchintanai songs, twenty letters, called tirumuham, and about 1,500 sayings, or arul vachakam. “Our Gurunathan,” the very first song in Natchintanai, relates the teachings of Chellappaswami and projects to everyone who sings it the depth of Yogawami’s affection for the soul who brought him into the light and into deeper realizations. It begins: §

He made me to know my self, our Gurunathan.

On my head both feet he placed, our Gurunathan.

Father, mother, guru—he, our Gurunathan.

All the world he made me rule, our Gurunathan.

Previous karma he removed, our Gurunathan.

Even “the three” can’t comprehend our Gurunathan.

He sees neither good nor bad, our Gurunathan.

As “I am He” he manifests, our Gurunathan. §

Yogaswami worked intuitively, responding to those who came according to “inner orders.” In explaining this process, he once said, “I do nothing. I can do nothing. Everything you see, that is done by what comes from within.” Another time he said, “When you come here, what will happen was settled long ago. We go through it; you bring it, but it all happened long ago. Sit and be a witness.” Swami explained the process: “When you are pure, you live like water on a lotus leaf. Do what is necessary, what comes to you to do, then go on to the next order you receive, and then to the next that comes.” §

He advised, “Boldly act when you receive orders from within. You need not wait until all details are in order. If you wait for everything to be worked out, you may miss your chance. Have faith and do the work that comes from within. Money will trail after you if you are responding to divine orders. Helpers will come. Everything will come. You have only to follow carefully that which comes from within.” §

When asked how to find one’s inner voice, he said, “Summa iru. Be still! Be still, and what you need will come to you.” “Summa iru!” was his constant command. He practiced it and heeded the answers that came. §

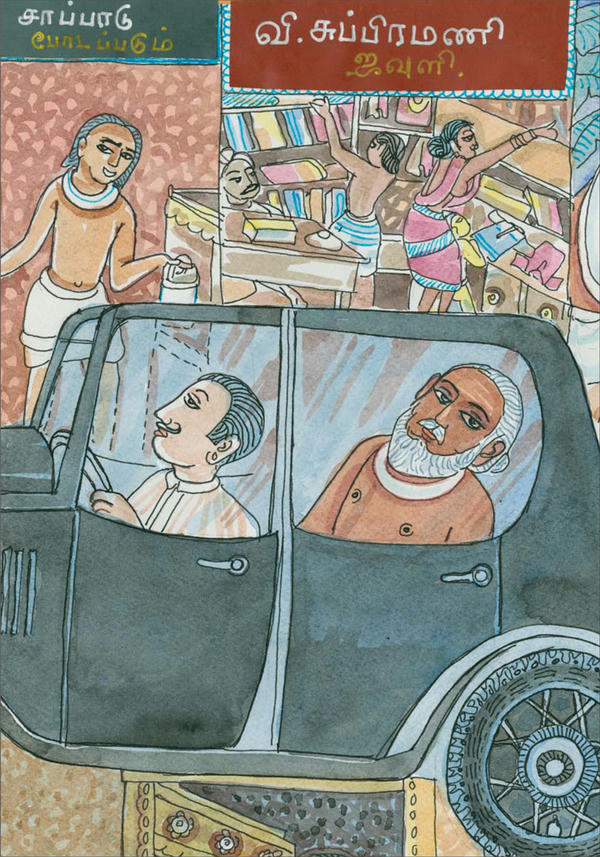

Someone would ask him a question and he would wait to feel his orders. If he felt no orders, he would do nothing until orders came. Once a man drove up to Swami as he was walking through town and asked if he could drive him anywhere. “No orders,” Swami replied and waved the man on. A few minutes later the driver came by and stopped again. “Now I have my orders,” Swami said, and got into the car. §

Sometime in the 1930s, two elderly German matrons set sail for India in search of truth, light and the good path. For months they endured arid austerities and boiled water as they searched out and spoke with every sadhu and holy man they could find. Their itinerary included Tiruvannamalai, the popular destination for seekers, where the renowned mystic and master of Advaita, Ramana Maharishi, had lived for decades on the sacred Arunachala Hill in a humble ashram. §

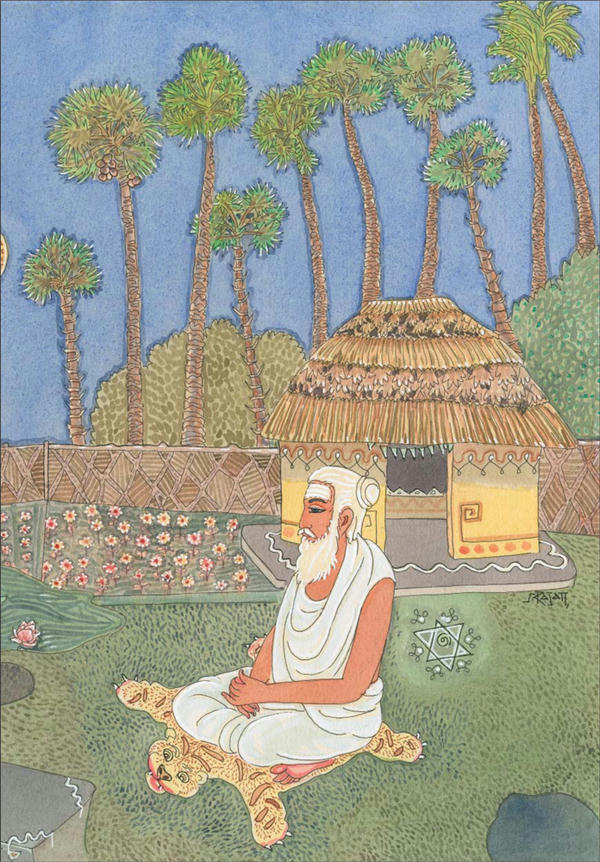

Traveling south, they eventually crossed the Palk Strait and entered Ceylon. From Colombo they made their way north to Jaffna where, it was said, one of the Great Ones lived. Locals stared unabashedly as the pair navigated dusty roads in long, frilly dresses, lace gloves and sun-thwarting parasols of dubious design. They found Yogaswami in his small thatched hut. Offering their obeisances, the two seekers sat on the woven mat he offered and drank dark Ceylon tea with the dark-skinned master who listened to the story of their pilgrimage and to their queries about the nature of Truth. §

“So, you asked these same questions to others?” Yogaswami inquired. “Yes, Swami,” they replied. “What did Ramana Maharishi tell you, then?” Intrigued that Swami knew of their visit, the elder responded, “His only words to us were ‘One God. One World.’” “I can do no better than that. You may go,” Yogaswami said abruptly. With that, the two departed, cherishing the darshan of one of their century’s enlightened souls.§

My Meeting with Jaffna’s Sage

Dr. James George, former Canadian High Commissioner to Ceylon, was profoundly influenced by Swami. He wrote the following account. §

The Tamils of Sri Lanka called him the Sage of Jaffna. His thousands of devotees, including many Sinhalese Buddhists and Christians, called him a saint. Some of those closest to him referred to him as the Old Lion, or Bodhidharma reborn, for he could be very fierce and unpredictable, chasing away unwelcome supplicants with a stick. I just called him Swami. He was my introduction to Hinduism in its pure Vedanta form, and my teacher for the nearly four years I served as the Canadian High Commissioner in what was still called Ceylon in the early sixties when I was there. §

For the previous ten years I had been apprenticed in the Gurdjieff Work, and it was through a former student of P. D. Ouspensky, James Ramsbotham (Lord Soulbury), and his brother Peter, that, one hot afternoon, not long after our arrival in Ceylon, I found myself outside a modest thatched hut in Jaffna, on the northern shore of Ceylon, to keep my first appointment with Yogaswami. §

I knocked quietly on the door, and a voice from within roared, “Is that the Canadian High Commissioner?” I opened the door to find him seated cross-legged on the floor—an erect, commanding presence, clad in a white robe, with a generous topping of white hair and long white beard. “Well, Swami,” I began, “that is just what I do, not what I am.” “Then come and sit with me,” he laughed uproariously. §

I felt bonded with him from that moment. He helped me to go deeper towards the discovery of who I am, and to identify less with the role I played. Indeed, like his great Tamil contemporary, Ramana Maharishi of Arunachalam, in South India, Yogaswami used “Who am I?” as a mantra, as well as an existential question. He often chided me for running around the country, attending one official function after another, and neglecting the practice of sitting in meditation. When I got back to Ceylon from home leave in Canada, after visiting, on the way around the planet, France, Canada, Japan, Indonesia and Cambodia, he sat me down firmly beside him and told me that I was spending my life-energy uselessly, looking always outward for what could only be found within.§

“You are all the time running about, doing something, instead of sitting still and just being. Why don’t you sit at home and confront yourself as you are, asking yourself, not me, ‘Who am I? Who am I? Who am I? Who am I? Who am I? Who am I?’” His voice rose in pitch, volume and intensity with each repetition of the question until he was screaming at me with all his force. §

Then suddenly he was silent, very powerfully silent, filling the room with his unspoken teaching that went far beyond words, banishing my turning thoughts with his simple presence. In that moment I knew without any question that I AM; and that that is enough; no “who” needed. I just am. It is a lesson I keep having to relearn, re-experience, for the “doing” and the “thinking” takes me over again and again as soon as I forget. §

Another time, my wife and I brought our three children to see Yogaswami. Turning to the children, he asked each of them, “How old are you?” Our daughter said, “Nine,” and the boys, “Eleven” and “Thirteen.” To each in turn Yogaswami replied solemnly, “I am the same age as you.” When the children protested that he couldn’t be three different ages at once, and that he must be much older than their grandfather, Yogaswami just laughed, and winked at us, to see if we understood. §

Yogaswami dwelled in a simple hut, suiting a yogi’s simple needs, without electricity or running water. Thousands of seekers came to him, and each took away the perfect message, full of spiritual insight that was often surprising.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •§

At the time, we took it as his joke with the children, but slowly we came to see that he meant something profound, which it was for us to decipher. Now I think this was his way of saying indirectly that although the body may be of very different ages on its way from birth to death, something just as real as the body, and for which the body is only a vehicle, always was and always will be. In that sense, we are in essence all “the same age.” §

After I had met Yogaswami many times, I learned to prepare my questions carefully. One day, when I had done so, I approached his hut, took off my shoes, went in and sat down on a straw mat on the earth floor, while he watched me with the attention that never seemed to fail him. “Swami,” I began, “I think...” “Already wrong!” he thundered. And my mind again went into the nonconceptual state that he was such a master at invoking, clearing the way for being. §

Though the state desired was thoughtless and wordless, he taught through a few favorite aphorisms in pithy expressions, to be plumbed later in silence. Three of these aphorisms I shall report here: “Just be!” or “Summa iru” when he said it in Tamil. “There is not even one thing wrong.” “It is all perfect from the beginning.” He applied these statements to the individual and to the cosmos. Order was a truth deeper than disorder. We don’t have to develop or do anything, because, essentially, in our being, we are perfectly in order here and now—when we are here and now. §

Looking at the world as it is now, thirty years after his death, I wonder if he would utter the same aphorisms with the same conviction today. I expect he would, challenging us to go still deeper to understand what he meant. Reality cannot be imperfect or wrong; only we can be both wrong and imperfect, when we are not real, when we are not now!§

The Master’s Way

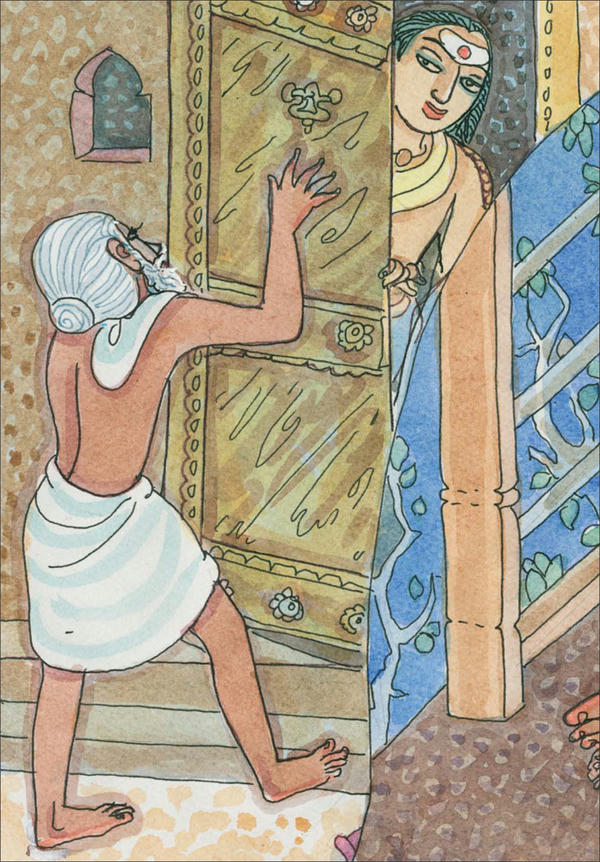

One devotee was in serious need of Yogaswami’s help, but was afraid to approach him, fearing that his mind would be an open book to Swami. He was ashamed of the promiscuous thoughts that haunted him, but was an ardent devotee and couldn’t keep away either. On his day off from work he made up his mind to go. He got up early, had his bath and put on clean clothes, saddened that his heart was not clean as well. Unable to control his mind he found himself descending further into sinful ways, with thoughts so despicable that he could not even discuss his problem with his friends, or his family, who would surely despise him if they knew. He decided to throw himself before Swami and cry his heart out. §

On the way, he hoped that Swami would not be in meditation, because then he would surely perceive his crude fantasies. Entering the ashram, he found Swami happily conversing with some disciples. “I have escaped,” the man thought as he prostrated and worshiped the satguru. With a wry smile, Swami looked straight into his eyes and said, “I know everything from your head to your toes. I know all your thoughts—not only yours, but everybody’s. I am in everybody. You do not know this, because you think of yourself as separate from others. Learn to consider yourself as the same as others and not separate.” Then, taking the camphor tray that was burning before him, he gave it to the devotee and said, “Take this light and, considering everyone here to be Siva, worship them.” §

It was Siva Yogaswami’s habit to visit the homes of close devotees, usually without notice, but always to the delight of the family, who regarded even the shortest sojourn as blessings enough for a lifetime. He often arrived in the hours before lunch, and on rare occasions he would stay overnight. Some devotees, hopeful of such a visit, prepared each day’s meal in the expectation, however uncertain, that Swami would arrive at their door. In her book Saint Yogaswami and the Testament of Truth, Ratna Ma Navaratnam tells of her family’s association with Yogaswami. §

The meaning of Saint Manikkavasagar’s famous plea—“Thou gavest Thyself to me, and takest myself to Thee. O Shankara, who hast gained more?”—dawned on us faintly, as we saw our parents revolve in the orbit of the guru’s light. It was in the early thirties that, at our father’s bidding, we took to the serious study of Tiruvasagam, which in turn served to illuminate the profound significance of the God-Guru in our spiritual quest.§

In all these early associations, Swami continued to be a distant star in the firmament of our lives till the last week of May, 1939, when he blazoned as a shaft of immense magnitude. Our father stumbled over a stone heap at the gate of his newly built house, called “Chelliam Pathi,” and had a fall, but escaped any serious injury, except a sprain and strain of the ankle which confined him indoors during the month of April, 1939. After the observance of the Chitra-Purnima fast, he developed fever with slight digestive upsets, and after a fortnight his condition remained static. It did not improve nor deteriorate.§

Late in the evening of the 28th May, our father called for mother and all his children, and asked us to switch on all the electric lights and spread a white cloth on the chair near his bed, and bade us sing. He also indicated that we should worship him who shall come, by prostrating at his feet. We did not understand the subject of his discourse. Though it seemed so enigmatic, we obeyed his injunction mechanically and awaited.§

At the sandhya [dusk] hour, with the waxing moon of Vaikasi shedding its translucent light, he came with his umbrella tucked under his arm pit, and opened the garden gate. Swami’s voice reverberated as he called out my father’s pet name, Sinnathamby, and walked right up to his bedroom, ignoring midway my mother’s prostrations amidst tears. Then was enacted a tuneful communion too sacred for communication. §

At the sight of Swami, my father tried to rise up from his bed, but the guru took both his frail yet cooped hands and held them against his chest and sang. It was a song that conveyed the bliss which awaits the bondsmen of Siva! His voice resounded from time to eternity. Then he took the holy ash out of the conch shell on the bed table and placed it tenderly on my father’s forehead. We saw our father’s face gleaming in sweet communion:§

It was not a parting. It was a promise fulfilled, an assurance of the certitude of Siva’s beatific bliss! He arose and left us bewildered. It seemed to us, in passing, strange that Swami had not offered a word of comfort to any of the distressed inmates. It was his way. Oru pollappum illai! [“There is not one wrong thing!”] It was his will that we simply be, summa iru. We were merely spectators in this magnificent spectacle of the play of guru’s grace! My father attained samadhi on the night of 30th May 1939. §

Here was an introduction to increase our faith and clear all wavering doubts in the guru, whose Siva Jnanam, God-illumination, was a source of mystery as well as perennial attraction. It was the beginning of a new phase when, little by little, we learnt to draw from the guru’s bank of grace. All resistance faded away. The magnet proved irresistible; and the realization dawned on us that the guru art all, after the agonising parting from a priceless treasure in our lives!§

Just as his paramaguru, Kadaitswami, loved to march through the marketplace, Yogaswami could frequently be seen in a 1940s black Ambassador exploring the entire peninsula or visiting a distant devotee’s home unannounced.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •§

Subsequently Ratna Ma Navaratnam and her husband Thirunavukarasu became close devotees. Their home was a short walk from Yogaswami’s ashram, which she would visit every day. Thiru was often Yogaswami’s chauffeur, and kept his black Ambassador polished and ready inside its small garage whenever called to duty. Ma, a brilliant author and educator, applied her linguistic skills to writing of her experiences with Swami and virtually every word she heard him speak. She would go to the hut mornings and evenings, sitting quietly in the back as the day’s events unfolded. Once home, she would record conversations word for word, along with visitors’ names, and, especially, Yogaswami’s upadeshas. §

Stationmaster S. Vinacithamby described his experiences.§

Sometimes when Swami stayed in our house he would spend hours in deep meditation. Seeing him seated in the lotus pose as the Lord of Meditation on my return from work would enrapture me. Early morning when we would wake up, seeing Swami lying on the bed, he looked like the Lord of Serenity. On seeing that form I would sense that we were looking at God, thus proving the words of that rare mantra “I am He.” §

Even when Swami was not there, it was natural to recall his divine form and sagely words. I recollected that he once said, “You can see God only through God.” As I remembered this, the certainty arose that there was no greater God than Yogaswami, who was constantly seeing God everywhere, within and without. §

In this state of mind I went to the ashram at Columbuthurai to see Swami, who was seated amidst a few devotees. Without forethought, I fell at his feet and worshiped him. From that day onward, until he attained mahasamadhi, whenever I went to see Swami I worshiped him, despite his saying, “It is not necessary to worship in front of people. It is not necessary to fall on the ground. It is sufficient if you worship mentally.” §

One day he called me by name and queried, “What is the one thing God cannot do?” Hearing the question, I was shocked. When it is said that God is all-powerful, is there something He cannot do? Swami quietly said, “You need not answer now; you can give the reply when you come in two days’ time.” When I came home, the question kept resounding in my mind. I could think of nothing else. Then a section I had studied in the Mahabharata came to my mind. When Krishna asked what could be done to prevent the war, Sahadevan’s reply was, “If I bind you straightaway, the war can be prevented.” Krishna responded, “How will you bind me?” to which Sahadevan replied that he would bind his Lord with the fetters of love. This seemed to me a satisfactory answer to Swami’s question. §

Two days later, when I went to see Yogaswami, I gave my reply: “When God is captured by the love of the devotee, He cannot free Himself.” Hearing my answer, he challenged, “How can that be? You can bind God by love only if love is different from Him. You cannot separate God from love. God is love.” He continued, “The one act God cannot do is to separate Himself from us, even for a moment.” By this device my guru impressed on my heart that God does not separate from us even for a trice and is always within us as the Soul of our souls. Now, since Swami is my God, I began to meditate on the fact he is the God who is inseparable from me. When a person seeking his blessing prostrated before him on the cow dung floor, Swami would often say, “Look, I am worshiping.” §

A devotee named Nagendran recalls when, as a boy, during the initial years of World War II, he observed Siva Yogaswami having lunch at his uncle’s house near Colombo. He begins with a description of the state of affairs in those troubled days. §

The Great War between England and Germany had begun in 1938. France and later Russia joined England in the war against Germany. Czechoslovakia, Poland, Holland, Norway, Sweden and Denmark were overrun by Germany and Italy. England and its Allies were fighting a strenuous rear-guard battle to save themselves and the rest of Europe. §

Australia and Canada had sent forces and were fighting alongside England and its Allies. The English colonies of India, Ceylon, Madagascar and other colonies in Africa were all mobilized to support the war. The hard-fought battles and the routs of the Allied forces were headlines in the Ceylon daily papers. England had the full support of the people I knew in Ceylon. Hitler and Mussolini were detested names. Every evening my father and his friends would meet at the verandah of our house in Colpetty, near Colombo, to discuss and analyze the battles. The United States had just declared war on Germany, Italy and Japan and sent forces to Europe under General Eisenhower to fight alongside England and its allies. §

My father would tell his friends, “You see, America has joined the war. It is a moving mountain. Germany and the Axis powers will now be crushed.” His friends concurred. But the war had not as yet had much impact in Ceylon. As boys of seven and eight, we listened attentively, from behind the scenes, to these discussions among the adults. §

Uncle Ramanathan was a vegetarian. Crisp and pithy sayings of Hindu sages in large, green Tamil script were framed and hung in the drawing room. One of the scripts read, “Persons who have entrusted themselves to God should never let go of Him.” During my visits there, I heard my uncle and other elders talk of Yogaswami in hushed and reverent tones. §

I had my first glimpses of Yogaswami when he visited my uncle’s house. Yogar was of medium height and build. His countenance was rugged and dark. Long, white-silver hair flowed back from the high forehead and was tied in a knot at the back of his head. He would occasionally untie the loosening knot and tie it firmly back in place. His forehead and body had no tiruniru [sacred ash], which was unusual for a holy man. No rudraksha necklace or garlands adorned his neck. He was a plain, unvarnished man. The significance of this simplicity only dawned on me much later. §

Lunch would be served during his visit in the midst of devotees invited by my uncle. Woven mats were laid out on the floor, making a square in the large drawing room. A plantain leaf was placed first before Yogaswami and then the devotees. Steaming white rice and fresh vegetables, without chilis or other spicy condiments, were served on the leaves. Yogar would sprinkle a few drops of water on his leaf, utter a few words of blessing and commence his meal. Only when he had taken the first bite would the devotees begin their lunch. §

His meal did not take more than a few minutes. He would then rise, go out with a chembu [a bronze vessel] of water and wash his hands in the garden compound. The devotees quickly finished eating and washed their hands as well. We always ate in the traditional way, using the fingers, after rinsing them first. Spoons and forks were never used to consume a meal. §

The room was then cleared and swept. Yogar would seat himself on the mat with devotees gathered around to hear his words of wisdom. Such discourses were terse, and he would abruptly leave the house a short time later. During one such visit, we children were upstairs. We knew we would be a disturbance if we came down. No disciplinary steps were required to keep us upstairs. The atmosphere was such that we knew this was the behavior that was appropriate and required of us. §

While Yogaswami respected all religions and never spoke critically of other faiths, he was strict in protecting and promoting the tenets of Saivism among the Tamil Saiva people. Dr. S. Ramanathan observed: §

Swami was a staunch upholder of the Saiva customs and ways of worship. He taught that properly conducting pujas in temples and homes, and observing the festivals with faith and devotion bring benefits to the individual and the entire world. As an example, Swami once related the following episode. There was a Government Agent in Jaffna named Dyke. He went to Poonakari during the dry season. There were no irrigation facilities there. He asked the villagers, “Without irrigation, how do you cultivate?” Someone replied, pointing to the Pillaiyar temple, “If we pray to Lord Pillaiyar, we will get rain.” The temple priest had a bath and, following all ritualistic details, went to the temple and prayed for rain. There soon was a huge downpour, which caused a flood. Dyke had to wait three days for the waters to subside before he could return to Jaffna. §

Strengthening Saivism

Swami worked to encourage and revive the proper observance of traditional practices. In his own hermitage, most evenings at dusk, a sacred standing lamp would be lit and he would have devotees sit on the cow-dung floor in a semicircle facing him, loudly singing devotional songs, sometimes from texts like the Tirumurai, other times from his own Natchintanai lyrics. Swami insisted that all the children, especially those studying music, should learn the ancient hymns. He challenged, “What is the use in singing ordinary verses when it is so much better to study and sing the powerful Tirumurai.” S. Ampikaipaakan notes: §

Swami personally took many steps to promote Saiva religion including conducting Saiva Siddhanta philosophy classes and coaching classes for the proper manner to recite Tirumurai and also to teach and give new life to Puranic song and storytelling. Swamigal wanted to see that Puranams were read in the temples and ashrams regularly. Swamigal used to say that all miseries afflicting the Tamil community will go away by reading Kandapuranam and Periyapuranam. §

V. Muthucumaraswami remembers another way Swami encouraged everyone to follow the Saivite saints: §

When Swami Vipulananda wanted to resuscitate the Vaidyeshwara Vidyalayam at Vannarpannai around 1945, it was Yogaswami who gave him the first donation of a rupee and blessed this move. This institution has now grown like a big banyan tree under whose shade many youths enjoy a true education with a deep religious basis. Swami wanted to revive Hinduism by inspiring people to follow the real ideals of the four great Saiva saints. And great was his joy when he heard that the portals of the Sivan temple at Vannarpannai had been opened to the harijans.§

S. Shanmugasundaram of Colombo shared:§

Swami stressed the importance of a proper shrine room in every Hindu household. He suggested that a new and special shrine room should be included in every new house constructed. This bit of advice was well taken by Mr. Vairamuthu. In the year 1932, he constructed a new house for himself and his family in Colombo, making a point to include a large, beautiful shrine room right in the center of the house. §

The construction was completed in due course and he was to move into the new house on a certain date. He had invited several friends and relations to a grand reception to take place at 6pm. By 3pm all arrangements had been completed and Mr. Vairamuthu sat in front of the house musing to himself, “What a glorious thing will it be if Siva Yogaswami would step in right now and bless the house.” §

Lo and behold! Just at that time, a car stopped in front of the house and Yogaswami stepped out. Mr. Vairamuthu ran to the car, welcomed the swami and brought him into the house. Swami barked, “I don’t have much time to spare. I was passing this way and I thought I will drop in here for five minutes. Now show me your shrine room.” He was taken into the shrine room, from where he blessed the whole house. He passed the camphor flame to Ganesha, Murugan and Siva and asked Mr. Vairamuthu whether he had any prasadam to offer him. Mr. Vairamuthu offered all that he had, but Swami took one item of each and remarked, “I have done the job for which I came,” left the room and the house, got back into the car and drove away.§

Swami opposed the ritual sacrifice of animals, which was the custom of the day at smaller, village temples. Dr. Ramanathan recalled how he spoke against it and brought about change.§

There was an old Aiyanar temple amid the paddy fields in our village. Every year the people celebrated the Pongal festival there with a huge sacrifice. Goats and cocks were killed and offered to this village guardian Deity. One day Swami returned from Anunnakam, looked at me and said, “I saw many corpses in your village,’” referring to the goats and cocks that had been sacrificed at the temple. The power of Swami’s compassion for those animals and birds eventually stopped this sacrificial practice. The temple authorities, who once refused to stop this practice, even when the people of the area arose in a storm of protest, now stopped it of their own accord. §

Tolerance and Compassion

A strict vegetarian, Swami also abstained from alcohol, though he smoked cigars in his senior years. Still, he was not puritanical about life. A follower recalled: §

There were many devotees who participated actively in the prohibition movement in Jaffna. But one devotee had a large liquor store and traded in it. Swami saw nothing wrong in this, for he never considered anyone as a sinner. He considered all as different gems strung together on the chain that was Siva. One of Swami’s close devotees learned that he should not differentiate even those who indulge in alcohol in the following manner. §

He was the principal of a school and was very friendly with a person who helped greatly in the development of the school. However, being an extreme disciplinarian, when he learned that his friend was a heavy drinker, he severed all connections with him. But when it was time to open a school building to which his former friend had made tremendous contributions, he was faced with a dilemma. With the thought of his friend worrying him, he went to Swami, who greeted him with the words, “Look here! We need drunkards, too. Even in a person considered to be a bad man may be some good qualities not found even in Mahatma Gandhi. Therefore, we should move with such people showing customary friendship and not discard them.” §

Swami urged devotees to not label people as good or bad: §

See everyone as God. Don’t say, “This man is a robber. That one is a womanizer. The man over there is a drunkard.” This man is God. That man is God. God is within everyone. The seed is there. See that and ignore the rest. Are you a good man or a bad man? Who is bad? There is no one who is bad in the world. No good man, no bad man. All are.§

While Yogaswami accepted all people as they were, without discrimination, he was not passive about the problem of alcohol abuse in the community. In the 1950s he mobilized his devotees to campaign in favor of prohibition laws. §

S. Shanmugasundaram recorded another incident that illustrates Swami’s tolerant and compassionate outlook.§

On one occasion there was a crowd of about twenty-five devotees in Swami’s hut and everyone was listening attentively to his stories, which contained gems of spiritual wisdom. Suddenly Swami observed that one of the devotees was somewhat uneasy. He immediately called him forward, placed something in his hands and told him he could go. The man left the place happily but somewhat shyly. §

Yogaswami then explained to the remaining devotees, “He is an attorney-at-law and a good devotee. Unfortunately, he has become slave to a bad habit—taking some liquor in the evening every day. He was getting uneasy because the pubs close at 6pm and he did not have enough time to go home to fetch some money and get back to the pub before it closed. So I gave him the necessary money and sent him away in good time. If he does not take his drink, he cannot eat and he cannot sleep.” §

This is an instance of Swami’s love and concern for his devotees. He had a most sympathetic heart and before he tried to reform anybody, he captured their love and admiration through his benign care and concern. He did not attract devotees through magic and material gifts, but through love and sympathy.§

Swami’s Natchintanai “Call Not Any Man a Sinner” conveys his attitude:§

Call not any man a sinner!

That One Supreme is everywhere you look.

Ever cry and pray to Him to come.

Be like a child and offer up your worship.

Forswear all wrath and jealousy;

Lust and accursed alcohol eschew.

Associate with those who practice tapas,

And join great souls who have realized Self by self.§

Every devout Hindu family hopes, one day, to feed the satguru, and Yogaswami’s devotees were always ready for his unexpected knock on the door. A few of the ammas were world-class cooks, and he stumbled upon their homes a little more often.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •§

A story from S. Shanmugasundaram illustrates Swami’s compassion, his close familiarity with the Jaffna people and his acceptance of the entire spectrum of humanity.§

A close devotee of Yogaswami went to Swami’s hut to have his darshan. Swami invited him to sit and then asked whether he had come in his car. When the devotee replied in the affirmative, Yogaswami said, “OK, come, let us go for a drive.” He got in the car and asked the devotee to drive south. After they had gone about ten miles, Swami asked him to stop, turn and drive down a particular road. After about four miles, Swami said, “Your house must be somewhere here. Let us stop and go to see your sick wife.” §

The devotee was amazed. Swami had never visited his home, and he had never said where he lived. To his knowledge, Swami also did not know anything about his wife’s illness. Lo, the spot where Swami ordered him to stop was exactly where his house stood. With awe and respect, the devotee got down and took Swami inside. The wife was bedridden, so Swami went into her room, had a close look at the patient, chatted with her for a few minutes. When he came out, he did not speak a word, and the devotee did not ask any questions. §

At that time, somebody from the back garden shouted something and Swami asked who it was. The devotee replied, ”That is my father-in-law, Swami; he is a peculiar type of man. He is not interested in religion or dharma. He is entirely self-interested and is only bent on making money all the time.” §

Swami then remarked, “This world is like an ornament worn on Siva Peruman’s chest. That ornament is studded with various stones, like rubies, diamonds, sapphires and emeralds. Some of them may be white and some may be of various colors. Some stones may be bright and some may be not so bright. But all the stones join to make the ornament beautiful. Similarly, the people on this planet, who are stones on the ornament, cannot be all alike. If all are good, the world cannot go on. Therefore, there is nothing wrong in your father-in-law’s attitude.” When they were driving back, Swami told the devotee that his wife would have to continue in bed till her death three years later.§

“The Day I Met Yogaswami”

Sometime in the late fifties, Sam Wickramasinghe of Colombo, a Sinhalese Buddhist, visited Yogaswami with a Tamil friend from Jaffna. Sam was a sincere seeker who had heard much about Yogaswami but had never visited him. Sam had met his new friend one day while walking along the seashore in Colombo. Soon after they exchanged greetings, the elder began telling him about Yogaswami with great enthusiasm, then scolded him for never having visited Swami: “It is disgraceful that you haven’t bothered to visit our sage who lives on this island.” The man offered to pay Sam’s train fare to Jaffna and invited him to live in his home in Tellippallai as long as he wished. Using the pen name Susunaga Weeraperuma, Sam recounted his experience in a small book he wrote in 1970, called Homage to Yogaswami. §

Being a devout Hindu, my friend sincerely believed that it was necessary to purify me as a preparation for the forthcoming visit to Yogaswami. In the mornings before sunrise, his wife would recite hymns from the Hindu scriptures. Frequently I had to dress in a white dhoti with sandalwood paste and holy ash applied liberally on my body as a necessary requirement before entering certain temples. I did not quite see the religious or spiritual significance of these rituals, but perhaps they added a certain color to these otherwise drab and solemn occasions. §

As the weeks passed by, much though I was enjoying the hospitality of my generous host, I was nevertheless beginning to feel rather impatient that we had not yet visited Yogaswami. Later I realized that my friend was sincere in his assurance that a preliminary period of preparation was absolutely essential before having an interview with Yogaswami. Nearly a month had passed and I was longing to return home to Colombo. §

As I was fast losing my earlier interest in Yogaswami, I finally decided to leave Jaffna without visiting him. When I broke the news of this decision to my friend, he gleamed triumphantly. “Ah, I think the right moment has come. Now that you are losing interest in him you are in a ready state to see him. We shall go tomorrow.” We decided to meet Yogaswami the following morning at sunrise, which was supposedly the best time for such a meeting.§

It was a cool and peaceful morning, except for the rattling noises owing to the gentle breeze that swayed the tall and graceful palmyra trees. We walked silently through the narrow and dusty roads. The city was still asleep. We approached Swami’s tiny thatched-roof hut that had been constructed for him in the garden of a home outside Jaffna. Yogaswami appeared exactly as I had imagined him to be. At 83 he looked very old and frail. He was of medium height, and his long grey hair fell over his shoulders. When we first saw him, he was sweeping the garden with a long broom. He slowly walked towards us and opened the gates. §

“I am doing a coolie’s job,” he said. “Why have you come to see a coolie?” He chuckled with a mischievous twinkle in his eyes. I noticed that he spoke good English with an impeccable accent. As there is usually an esoteric meaning to all his statements, I interpreted his words to mean this: “I am a spiritual cleanser of human beings. Why do you want to be cleansed?” §

He gently beckoned us into his hut. Yogaswami sat cross-legged on a slightly elevated neem-wood platform, which also served as his austere bed, and we sat on the floor facing him. We had not yet spoken a single word. That morning we hardly spoke; he did all the talking. §

Swami closed his eyes and remained motionless for nearly half an hour. He seemed to live in another dimension of his being during that time. One wondered whether the serenity of his facial expression was attributable to the joy of his inner meditation. Was he sleeping or resting? Was he trying to probe into our minds? My friend indicated with a nervous smile that we were really lucky to have been received by him. Yogaswami suddenly opened his eyes. Those luminous eyes brightened the darkness of the entire hut. His eyes were as mellow as they were luminous—the mellowness of compassion. §

I was beginning to feel hungry and tired, and thereupon Yogaswami asked, “What will you have for breakfast?” At that moment I would have accepted anything that was offered, but I thought of idli [steamed rice cakes] and bananas, which were popular food items in Jaffna. In a flash there appeared a stranger in the hut who respectfully bowed and offered us these items of food from a tray. A little later my friend wished for coffee, and before he could express his request the same man reappeared on the scene and served us coffee. §

After breakfast, Yogaswami asked us not to throw away the banana skins, as they were for the cow. He called loudly to her and she clumsily walked right into the hut. He fed her the banana skins. She licked his hand gratefully and tried to sit on the floor. Holding out to her the last banana skin, Swami ordered, “Now leave us alone. Don’t disturb us, Valli. I’m having some visitors.” The cow nodded her head in obeisance and faithfully carried out his instructions. §

Yogaswami closed his eyes again, seeming once more to be lost in a world of his own. I was indeed curious to know what exactly he did on these occasions. I wondered whether he was meditating. There came an apropos moment to broach the subject, but before I could ask any questions he suddenly started speaking. §

“Look at those trees. The trees are meditating. Meditation is silence. If you realize that you really know nothing, then you would be truly meditating. Such truthfulness is the right soil for silence. Silence is meditation.” He bent forward eagerly. “You must be simple. You must be utterly naked in your consciousness. When you have reduced yourself to nothing—when your self has disappeared, when you have become nothing—then you are yourself God. The man who is nothing knows God, for God is nothing. Nothing is everything. Because I am nothing, you see, because I am a beggar, I own everything. So nothing means everything. Understand?” §

“Tell us about this state of nothingness,” requested my friend with eager anticipation. “It means that you genuinely desire nothing. It means that you can honestly say that you know nothing. It also means that you are not interested in doing anything about this state of nothingness.” What, I speculated, did he mean by “know nothing?” The state of “pure being” in contrast to “becoming?” He responded to my thought, “You think you know, but, in fact, you are ignorant. When you see that you know nothing about yourself, then you are yourself God.” §