Chapter Seven

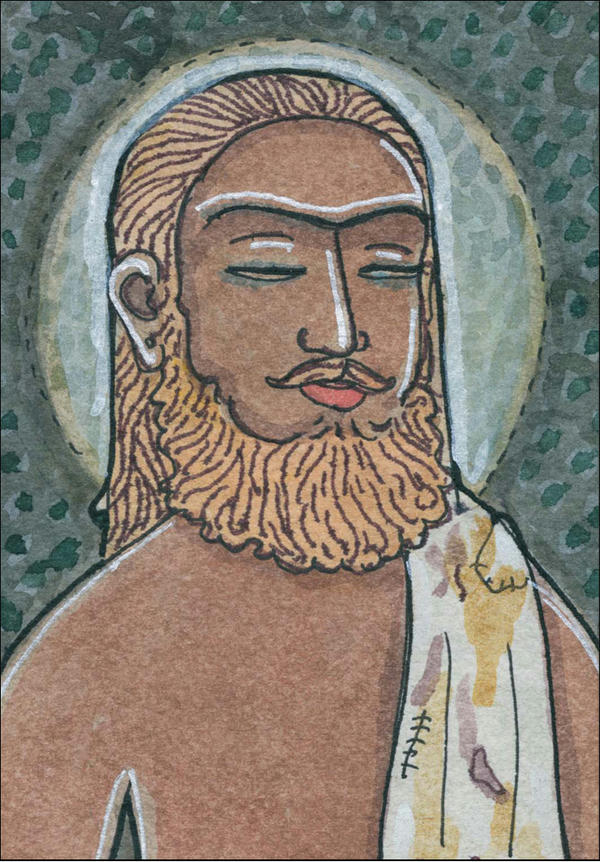

Chellappaswami, the Siddha of Nallur

Toward the middle of the 19th century, a farmer named Vallipuram of Vaddukkoddai married Ponnamma of Nallur. They built their home near Nallur Temple and cultivated the fields. The couple had two girls and two boys, one of whom was named Chellappa. From his youth, Chellappa devoted himself one-pointedly to the pursuit of the divine within himself. He was so introverted that his parents thought him addled. Eccentric as he was, Chellappa was a pure person, strict with himself and others. By all accounts he was born a yogi—people had predicted sannyasa for him even as a youngster. He would never ask for things, even food or clothing. If he wasn’t given what he needed, he went without. He had no friends. In fact, he went to any length to hide from people, spending every free minute alone. He was close to no one. His family never knew what he was thinking, nor could they coax him out of his shell. He only withdrew all the more for their efforts. §

As a young man, he had to be taken to school or he wouldn’t go. Once there, he would sit through the day hearing and speaking nothing. It was sheer torment for everyone. His classmates mocked him, and his teachers punished him constantly for his “daydreaming.” But nothing they did brought his mind down to earth. At home, he habitually sat quietly apart from others, lost in his thoughts or meditating, much to his parents’ dismay. They felt he was too serious and told him he should laugh and play like other children. He attended a Tamil primary school called Saiva Prakasa Vidyasalai at Kantharmadam, a mile from Nallur Temple. §

By the time he was sixteen, Chellappa’s peculiar distance from people was so pronounced that he routinely went for days without speaking to anyone at all. His parents feared something was seriously wrong with him, and from time to time took him to various doctors, astrologers and other learned men, seeking a sensible diagnosis. No one could help them understand their boy. His health was sound, though he was unusually thin, but no one knew his aloof mind. Nonetheless, he attended Jaffna Central College, a secondary school, where the medium of instruction was English. §

Chellappaswami was a difficult man to be near, fiery and outspoken, bold and taunting, preferring his own company and often mumbling nonsense. With his tattered veshti and unforgiving manner, it is little wonder only a few strong disciples drew close.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •§

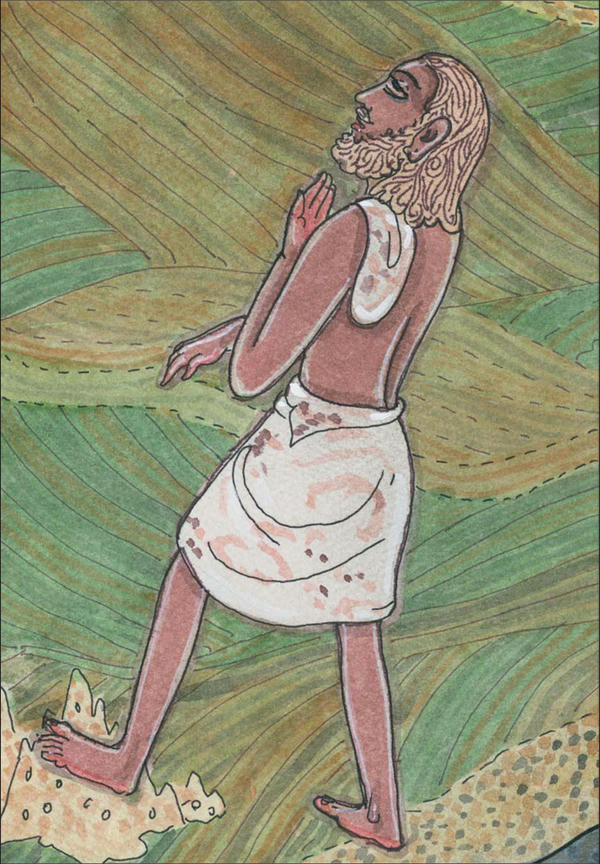

Later Chellappa took to wandering away into the countryside, to a far-off temple or village, where his family would inevitably find him, after a desperate search, meditating under a tree or aimlessly walking the roads. He patiently bore with their pleading and punishments but before long wandered off again. They learned finally to let him go. He would turn up, hungry and tired, after a week or two. It moved his mother to tears, and she prayed for him all her life. §

A Penchant for Solitude

After leaving school, Chellappa worked as a night watchman guarding a building adjacent to a cremation ground, spending the whole night outside in the weather, making an occasional circuit of the property. He was in his late teens at the time. His parents had resigned themselves to his austere predilections, yet he managed to appall them even further. It seems that after perfunctorily checking the building he was hired to watch, he would enter the cremation yard and sit through the night meditating, often near a still-smoking pyre. It is said he later worked at a small government office, but his penchant for solitude overcame his need for a salary.§

K.C. Kularatnam gave details of this period in Yalpana Nallur Terati Cellappa Cuvamikal (translated by Dr. Vimala Krishnapillai as Chellappa Swami of Nallur):§

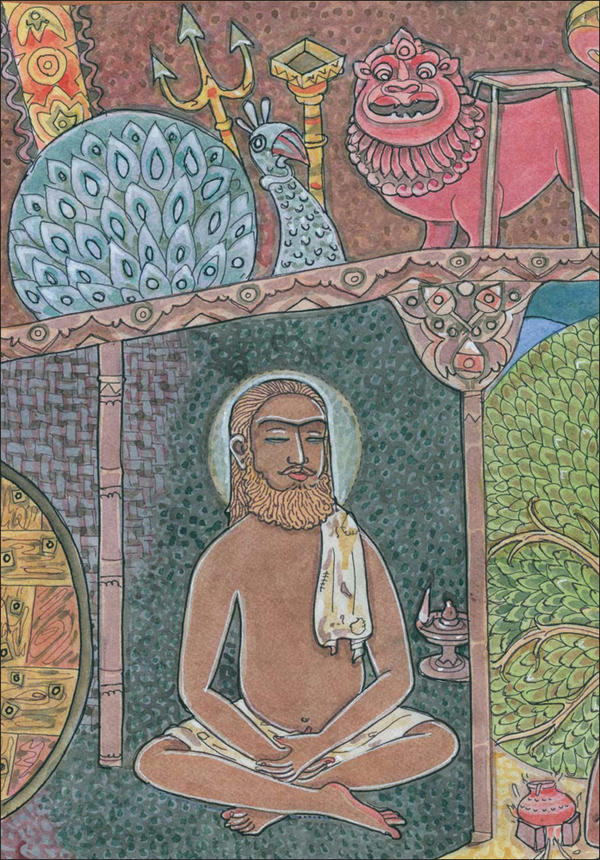

Chellappaswami frequently found refuge in Nallur Temple’s chariot house, a 12-meter-tall thatched tower in which Lord Murugan’s parade images and elaborate carts were stored. It was a dark chamber, well suited to the sage’s urge to be alone, to meditate for hours without distraction.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •§

Chellappa discontinued his studies after some years and commenced his employment as an arachi [public relations officer] at the Jaffna Kachcheri [District Secretariat]. Being a very efficient worker he received the admiration and the confidence of the authorities and was many a time entrusted to be in charge of the treasury. Though Chellappa enjoyed the high prestige of a privileged post, he was not enamored by it. He was ever dwelling on the inner kindling of his being. Irresistibly drawn towards jnanam, spirituality, there appeared changes in his habits, dress and movements. This intrigued many. Outwardly he carried on with his normal work without giving any room for others to talk about it. Inwardly, during the night when others were all fast asleep, he was engaged in mystic communion with Lord Murugan of Nallur and began to prate, “Father! Father!”§

When this flood of jnanam surged and overflowed outwardly, he appeared like a madman, like one possessed by the spirits, like an innocent child. He would speak to himself, repeat “Om, Om,” shaking his head, raise his right hand high, wave and shout loudly. He would not let anyone get close to him. He chased them away as they approached him. He neglected his job and finally left the Kachcheri. He then sat all day in the corner of his hut.§

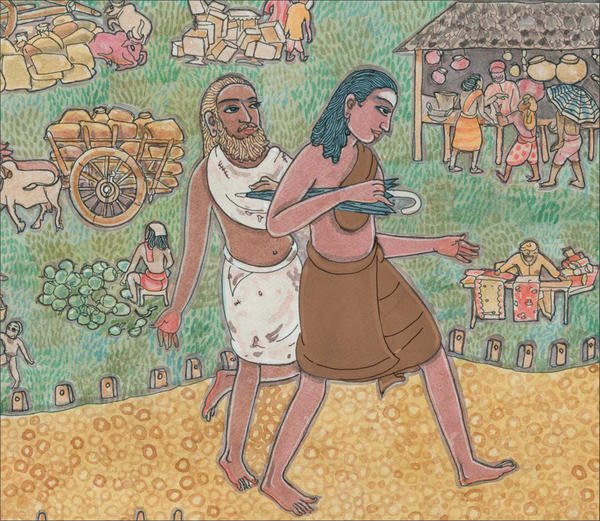

Kadaitswami visited Chellappaswami often, watching over his shishya’s meditations. The two were often seen marching together through the villages that dot the Jaffna peninsula, going nowhere in particular.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •§

Seeing him withdraw more and more into states they interpreted as aberrant, his relatives arranged special pujas for him in which the priests tried to exorcise the spirits they assumed had possessed him. To no avail. Chellappa was unmoved by all the fuss and unfazed by not being understood. On occasion he even took advantage of being thought mad. It could be his ticket to do just as he pleased, to wander or be a hermit as and when he was moved to. He would mix with the sadhus of Sri Lanka, listen to their stories and watch quietly as they debated philosophical intricacies. These were the things that engaged his mind.§

Understandably, the question of Chellappa’s marrying never came up, and when he met his satguru, Kadaitswami, he was perfectly free to follow him. Released, if reluctantly, by his family and society at large, he lived as a sannyasin from his early twenties. His already intense inner life was so heightened by the spiritual transformation his guru wrought within him that his relatives hardly knew him, nor did he know them from strangers. Everything about him changed and changed again. §

In a very short time, Kadaitswami carried him to the heights of God Realization, but Chellappa was a long time adjusting to the aftermath of this profound nonexperience. He spent long hours in deep meditation near the portico adjacent to the Nallur Temple teradi, a large shed in which Lord Murugan’s ornate festival chariot is stored, forty-five meters from the temple entrance. It was in those days a thatched chamber, about twelve meters tall and six meters on a side, housing the wooden parade chariot, with its two-meter-high wheels, and other parade paraphernalia which were brought out only during major festivals. In front stood a three-sided open pavilion bordered by a wrought iron fence.§

We read of the eminent history and grandeur of Nallur, Jaffna and Sri Lanka in Chellappa Swami of Nallur: §

Our country, Lanka, land of Siva, glows like gold in the Indian Ocean. The Tamil word eelam means “gold.” Saint Tirumular in his Tirumantiram has said that this Ellankai [Lanka, “island”] is an abode of Siva. There were many Iswaran temples dedicated to Lord Siva in this land and many siddhas lived and roamed this land. The traditions of the Siddha Parampara are deep rooted here. The greatness of these saints, who immersed their minds at the feet of Lord Siva, is beyond comprehension.§

Samadhi temples of these great siddhas abound in the Jaffna peninsula and throughout the Northern Province. Many jnanis and siddhas, from Kadaitswami to Yogaswami, have left their sacred footprints in and around Jaffna. Guru puja mandapams, the halls constructed near such temples, were not only centers of charity but also the seats of cultural and religious activities. §

Nallur [literally “good place”] is an ancient city in Jaffna. It was the capital city of Emperor Ariya Chakravarthi, whose sovereignty (1215-1240) was widespread. In fact, Rameswaram in Tamil Nadu was under his administration, and he earned the title Sethukavalar, the protector of Sethu [the isthmus between Tamil Nadu and Jaffna]. It was in Nallur that pure, refined Tamil and Saivaneri [the Saiva path] flourished. Situated very close to the king’s ancient palace was the Nallur Kandaswami [Sanskrit: Skandaswami] Temple of Lord Murugan. Around this temple, in the four directions, were built the sentinel temples for protection; Veyilukanda Pillaiyar Kovil in the East, Kailasanatha Sivan Kovil in the West, Veerakali Amman Kovil in the North and Sattanatha Kovil in the South. The royal flag and the royal seal carried, in the insignia, the symbol of the Nandi, which was continued by successive kings.§

Though the Portuguese destroyed the Nallur Kandaswami Kovil and even uprooted the foundation, there was a Saiva revival during the Dutch rule, around 1734. During this period, there lived several bards and poets who composed great religious hymns. Thus, Nallur was once again flooded with religious wisdom, jnanam. Srimat Ragunatha Mappana Mudaliyar, who was holding a high position in the Jaffna Kachcheri, appealed to the Dutch and got their permission to set up a Vel Kottam, where the vel, the insignia of Lord Murugan, could be installed for worship. §

Nallur Temple was a center of life for Chellappaswami. An ancient Murugan temple, with a shakti vel enshrined within its innermost sanctum, it is even today the most prominent Hindu temple of the Jaffna peninsula, some say because of the presence of the lineage. §

Kadaitswami visited Chellappaswami there often, and together they went on long walks and meditated at out-of-the-way places. One afternoon, on a particularly scorching day, while Chellappaswami was sitting in the shade in the Nallur compound, he suddenly put up his umbrella and held it there as if he were in the sun. Ten minutes later Kadaitswami arrived, and Chellappaswami put the umbrella down. Witnesses surmised that Chellappaswami had felt his guru coming and put up his umbrella to mystically shelter him from the hot sun as he walked. §

In the Guise of a Madman

In the weeks following Kadaitswami’s departure from the Earth plane, Chellappaswami lost all outward coherence, behaving like a madman, wild and unpredictable. He sat in the Nallur teradi portico for days and nights, motionless, hardly breathing, showing no hunger or thirst. He was an awesome figure, living in another world. Yet physically he was awkward, with protruding teeth and thin, hay-colored hair. People brought offerings of camphor, fruit and flowers, and sat blissfully at his feet. He spent so much time there that people referred to him as Nallur Siddhar, or Teradi Siddhar. §

He sat, meditated and ate in the shade of the bilva tree near the entry. At some point he took up use of a hut with clay walls and thatched roof across the road from the teradi in a corner of his sister Chellachi’s property. For some time she brought meals for him, but he would shout, “Go! Take it away! You have brought me poisoned food.” He cooked his own meals at the hut, and slept there or on the concrete steps of the teradi on a thin straw mat, living a simple life that would have great impact on others—that would, in fact, change the future of Saivism in Sri Lanka. §

When he wasn’t in samadhi, his demeanor was fierce. He threw things at anyone who approached for blessings, running and shouting after people who merely looked at him twice. People kept their distance, not comprehending this amazing being, yet sure, somehow, that he was special. Chellappaswami’s successor, Siva Yogaswami, wrote of the enigmatic sage:§

In derogatory language would he, my father, look at those who linger in the streets, and rebuke them menacingly. They note his insanity, Sinnathangam dear. His gait ever so stately, he rambles from place to place. All those who sight him feel inclined to mock and jeer at him, my dear. §

These were the days of British Christian domination, when a Hindu sage or swami had to disguise himself to continue his inner work, when sannyasins wore white, not orange, lest they be persecuted or thrown in jail. Indeed, Chellappaswami was not mad, but was likely instructed by his guru to behave this way to avoid harassment. Chellappaswami was a jnani who cloaked his greatness in unmatha avastha, the guise of a madman. Indeed, to the locals he was known as “visar (mad) Chellappaswami.” To protect him, at one point his family had him put in chains, giving even more credence that his behavior was for real. §

Chellappaswami would stagger in a rapture through the streets of Jaffna, talking aloud to himself in cryptic phrases, complex and confounding, addressing everyone and no one at the same time, perhaps to discourage unworthy devotees and perhaps to throw off suspicion from the British-controlled government that he might be a spiritual leader and therefore a threat to them and their evangelical efforts. It was a time in Jaffna when well over half of the traditional Saivite families had come under the influence, temporarily as it turned out, of the conversion-hungry Catholic, Anglican and other Protestant faiths.§

Years later, Yogaswami was under similar pressures and was also considered a madman by local people. But discerning villagers knew that these were the ones who were truly sane; these were the knowers of the Unknown spoken of in the Vedas. These men were sadhus in their last lives, and thus were naturally inclined to sit absorbed for hours or even days in meditation, fathoming the depths of consciousness. That the community as a whole did not comprehend this was of little concern to them. Chellappa Swami of Nallur offers this insight: §

In telling of their travels together, Yogaswami shared his amazement at how Chellappaswami would walk, eyes on the clouds, and yet he never stepped on the anthills that strew the land, while he, Yogaswami, managed to step into their fire even when he was watching for them.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •§

Though Chellappa Swami had openly declared, “Chellappa will not reveal himself,” devotees in large numbers came to him, affirming “Chellappa is our father, a good father who showers mercy on us, the golden father of Nallur.” Even people from far off places came to him with deep faith—to mention a few: Tiru Gnanasambanthar, Ramalingam, Thuraiyappah and Ponnaiah of Columbuthurai, Arumugam, Elayathambi, Thamotharampillai of Kantharmadam and Murugesu of Kambantharai.§

Swami was very kind to them. When some of his pupils said they wanted to follow the ascetic path, he remarked, “That life and you are poles apart. You had better get married.” When some said that their relatives were compelling them to get married and sought his permission, the swami would say, “Why should you ask me to get married? Go, go at once.” If anyone spoke about marriage, he would chide in a humiliating tone, bluntly saying, “Did you hear? The government agent wants me to marry his daughter. He wants me to marry. Shall I?’’§

Chellappaswami told Yogaswami that to make it known you are a guru, a realized one, is even madder than appearing insane. Ordinary people would give you no peace. They would chase you night and day to extract blessings, almost by force, without doing anything to deserve that grace. They would come for material blessings, to have their future revealed, or just to stand near in hopes of something miraculous. §

Mrs. Inthumathy (Amma) Navaratnarajah shares this image of Chellappaswami and thoughtful insights into his guise of lunacy in her manuscript Yogaswami, Life and Teachings.§

The great personage Chellappar sat on the chariot house step every day. Yet no divinity was visible on the dark-complexioned sadhu who sat with a vacant look on his face. Coarseness was the only visible sign. Even during festival times when the crowd was so dense that a ray of light would not pass through, he would sit on the step, his face shining, laughing to himself. Sometimes he would lie on the step, looking at decriers. Sometimes he would berate with belittling words those who were wandering about aimlessly. They would in turn abuse him, call him a lunatic and go away. He would not bother about this abuse and would continue to harangue them, taunting them to oppose him.§

Sometimes he would stand in Lord Skanda’s presence, before the sanctum, wearing rags, and scold in foul language those coming and going. At times he would wander to Tirunelveli, Columbuthurai and other places. People seeing him wander around would ridicule him as insane. He would stand begging before houses, accepting whatever was given. On some days he cooked rice and a curry. He did not sleep much. After midnight, using his hands as a pillow, he could be seen sleeping on the ground. §

His versatility with his hands in weaving palmyra and coconut leaves into various objects of art was the only factor that showed that he was not mad. But is this one factor alone enough for the crazy world to realize his sanity? §

Chellappaswami lived exhibiting the qualities of a madman and a great sage immersed in spiritual meditation. Those who were deluded by him considered him a madman. Those thirsting for spiritual knowledge saw him in his true colors—a man of deep knowledge. Siva Yogaswami saw him as the royal sage, who in the form of a guru redeemed and saved him. “At the teradi, I saw him, the crescent jewel of grace. He made me his own and showed me the way of bliss.” §

With these baffling disguises Chellappa wandered alone, hiding his real nature; so that no one realized his true self. Even scholars who were well-versed in Vedanta and Siddhanta, even those who had a long-standing friendship with him could not realize his true inner nature. Chellappa acted well the role of a lunatic he had taken on himself. Yogaswami once noted, “For forty years he acted the role he took without anyone suspecting, and went away.” §

Chellappaswami spoke cryptically, in a language that had to be deciphered. Yogaswami himself recorded some of his gems:§

“Intrinsic evil there is not,” and “Absolute is Truth which none can ever comprehend”—so saying, he would remain mute. “It is what it is, and there is none who can know fully, as it is concealed in dissimulation”—so uttered the lofty Chellappan, clad in ragged clothes, and haunting Kandan’s frontal courtyard. At those who frequent that resort, he will hurl abuse, my fond one. §

“That is so from endless beginning,” he would say and wander hither and thither. “It’s all illusive phenomena,” he muttered, “Who knows?” and “It was all settled long ago” and went about the outer courtyards of Nallur Temple and sat in the dirt, saying that all that dirt would frighten away the people who came to fall at his feet. I don’t think anyone ever got from him an answer to a question. I merely stood and waited behind him for the occasional gem that fell out of all the mad talk.§

Among the Sri Lankan Hindus, there are countless marvelous stories about the powers of a realized person, stories that would bring curiosity seekers if a guru proclaimed himself. Chellappaswami said that devotees who are ready, those few souls who understand the true nature of a satguru, will go through any barrier to be with him. Such a seeker will recognize and pursue the satguru in any disguise he wears. Were the satguru a homeless mendicant, a village pariah, the seeker would grow strong withstanding the disapproval the community might express in seeing him follow someone considered socially unworthy. §

The devotee seeking realization will not let anything stop him. Even if the guru chases him away, he will not be dissuaded from his path. He accepts as a blessing anything the guru does. He will change his form, his opinions, his intellect, his very nature, to bring himself into harmony with the guru. There are endless stories of people being sent away by a guru, only to come back in disguise. If that didn’t work, they would go away and undertake life-transforming tapas until they changed their nature and were able to return in good stead. §

Chellappaswami’s nephew, his sister’s son, lived in her house. The young man was hot-tempered and, even though he acknowledged Chellappaswami was a sage, often lost his temper with the swami because Chellappaswami used such harsh and filthy language toward him, his mother and other members of the family, sometimes offending their friends and visitors. §

One day Chellappaswami was standing by the open water well in the family compound, scolding his sister in a loud, angry voice. Running out of the house to defend his mother, the youth began screaming at Chellappaswami to stop. Chellappaswami yelled back at him, mocking his words. Suddenly the boy jumped across the two-meter-wide well to get at the swami, both fists flying as he landed on the other side. Chellappaswami touched him lightly on the chest and immediately all his anger was stilled. It vanished entirely. The boy just stood there, dumbfounded, blinking in shock, not knowing where he was. §

The family learned through the years to respect Chellappaswami’s advice. Once they and a few close friends planned a pilgrimage to Kataragama, the most famous of Sri Lanka’s Skanda temples, located in the tiger-infested jungles deep in the southern hills. They saved their money and talked about the journey for months ahead of time. Chellappaswami knew they were going. When the day finally came to depart, though, he said, “Why go searching? God is here.” They unpacked immediately, all but one of the party, who set out by himself. As it turned out, he never reached Kataragama. He fell desperately ill with malaria along the way and returned to Jaffna only after six months in the hospital and thousands of rupees in doctor’s fees. §

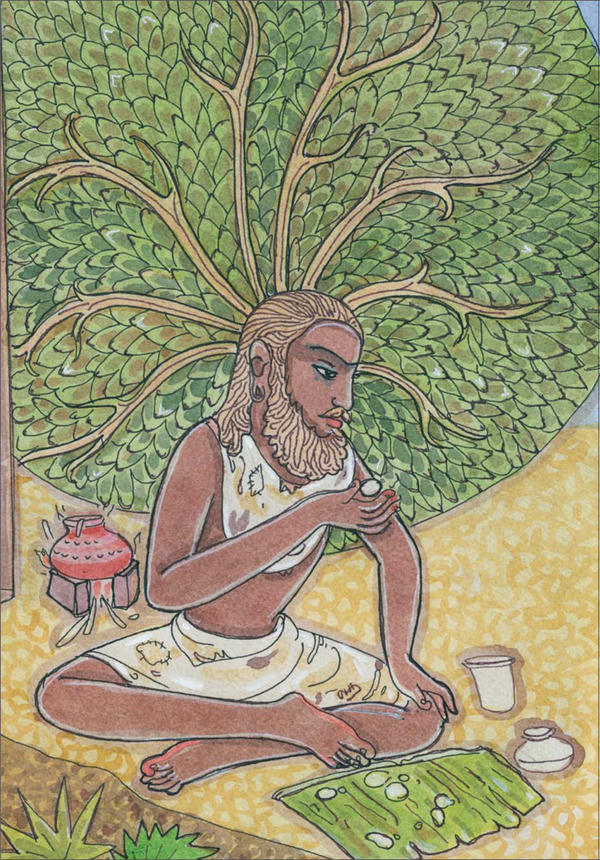

Chellappaswami kept a tight rein on his desires and appetites. His meals were taken in solitude most of the time, prepared on a simple wood fire in the shade of the Nallur temple bilva tree.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •§

Works of Wonder

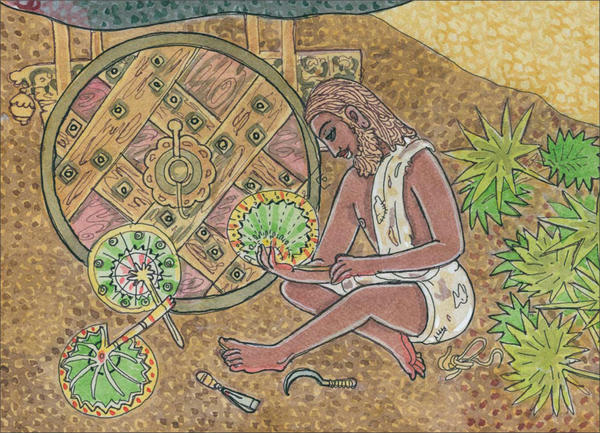

Most of the time Chellappaswami could be found in the shade of his thorny bilva tree, the famed Aegle marmelos, sacred to Lord Siva, since its leaves form a trishula. Protected from the tropical sun under its massive canopy, he talked to himself, meditated, ate his meals, sat and made fans and containers of various shapes from palmyra and coconut palm leaves. He often worked all day in the hot sun weaving the leaves into fans. Mastering the art requires patience and skill, and none was better at it than he. Each fan was of a unique design, no two alike. He gave the fans away to devotees and bystanders. It was a form of communion and blessing, imbued as they were with the implied meaning of protecting, cooling and relief from suffering. He also wove cadjan from coconut fronds, a thatch used for roofs, walls and fences. §

The mysterious siddha wielded great influence. One of the honored sons of Sri Lankan culture was Sir Ponnambalam Ramanathan, who founded the Ramanathan College for young ladies at Maruthanamadam at the edge of Jaffna town during Chellappaswami’s time. On the day of its grand opening, Swami was among the first to arrive. He walked in through the open doors and presented Ramanathan with one of his best fans, and said, “There is no intrinsic evil; finished long ago; everything is true; we know nothing.”§

The community attributes the school’s success to Chellappaswami’s blessing that day. The whole staff considered it extraordinary that this holy man had come to their school at this particularly auspicious moment on this most important day. §

Ramanathan did much for Saivism, including rebuilding the Sivan Koyil at Kochikadde, Colombo, with his own funds, decreeing that it be carved entirely from granite. The original temple had been built by his father, Mudaliyar Ponnambalam, in 1856. The reconstruction was completed in 1910. §

Chellappaswami would spend hours cutting and weaving the rigid fronds of the palmyra tree to make traditional fans, which people used to fend off the sweltering heat. Those who received his fans regarded themselves immensely blessed.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •§

Chellappaswami expected to be left alone. Even his own devotees approached only on invitation, visiting less on their initiative than his. If they needed anything from him, they would already have received it. He knew their minds. Devotees often sought his help at crucial times in their life. Here is an example from Chellappa Swami of Nallur: §

A child of Ramalingam of Columbuthurai was seriously ill. The parents were eager to take the child to Swami, but his mother-in-law warned them, “We do not know to what caste that madman belongs. Do not take the child to him.” Brushing off this old woman’s words, Ramalingam and his wife took the child to Swami. When he saw them, Swami ordered, “Kanakamma, bring the child here!” Giving instructions to take the child to a native physician for a particular medicine, he declared, “Your mother is speaking of caste. I swear by the Sun and the Moon that we are no other than Vellala caste from Vaddukkottai.” When Swami touched the child, the temperature went down, and upon receiving the prescribed medicine, the child was fully cured.§

Chellappaswami’s extraordinary self-discipline can be seen in the control of his appetite. If, during the preparation of any food, his mouth began to water in anticipation, he would shatter the clay cooking pot and forego that meal. This happen so often, Yogaswami described him as “one surrounded by broken pots.”

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •§

If strangers drew near, stopping out of curiosity to see what he was doing, he would scold, throw things and chase them away. He would throw anything—dirt, mud, rocks, cow dung, garbage—just so they would let him be. §

In every scolding, Chellappaswami corrected devotees’ misdeeds and touched the sorest and most sour area of their inner mind. They trusted him to know just where they were imperfect, just where they needed to change for spiritual progress. §

They hated these upbraidings, not only because they revealed those things most wanting to be hidden, but also because they were delivered with a spiritual force so penetrating that it felt like a deep psychic surgery. Yet, again and again they went back for more, receiving those incisive corrections as divine blessings. They invariably improved in the days and months after his fiery grace descended on them in all its terrible fury. Just being in his presence, receiving a modicum of that infinite shaktipata, transformed them, made them different, somehow better. §

Thus, he spoke like a spiritual king to those with an inner ear. Those few, the lawyers, the judges, all who were of a subtle mind, loved and feared Chellappaswami. He would curse them, beat them verbally and even physically. He was their inner guide, the guru that inspired them to fully live a spiritual life, and spiritual life was universally understood in Northern Sri Lanka to be the most exalted of human inquiries.§

Chellappaswami continued the parampara’s mighty mission of slowly but surely, step-by-step, awakening Saivism within the hearts and souls of Tamils everywhere on this lush, garden island. Were it not for him, there is no way of knowing whether Saivism would have survived into the 21st century. §

Then again, on rare occasions he paid no attention at all when people he had never seen before brought him flowers or prostrated in his presence. He sat impassively while they made their pranams. It was hard for them to discern if he knew they were there at all. No one ever knew what to expect from this perplexing spiritual giant. Yet all got exactly what they needed. §

This was Chellappaswami’s way—always the sage, never the saint. Many times he treated Yogaswami as if he had never seen him before, chasing him away and calling instead to some common passersby off the street, people who weren’t much interested in spiritual things. He would coax them sweetly to come near, then lecture, then berate in the vilest language imaginable, telling them what scum they were—living like animals, with no thought of God or their own souls, filling their bellies like pigs by day and sleeping like dogs at night, wallowing in endless desires, rushing down the royal road to hell, and so forth. He might go through every individual in the group, naming their secret vices, ticking off their private sins, abusing them right there in public. If they tried to leave, he followed them until he was through. He was unrelenting in giving forth his blessing, revealing the truth, no matter how great the humiliation. §

His greatest siddhi was to change the life force within people, hence change their lives. These psychic powers, which he received from Kadaitswami, Chellappaswami passed on to Yogaswami. The righteous anger of our sages is to this day called “white anger” by the Tamil people, the opposite of the hurtful black anger of the vitala chakra, below the muladhara chakra. §

Whenever in life the issue of the guru’s fierce scoldings arose, Yogaswami challenged, “Is not a big fire necessary to burn rubbish?” In his later years, Yogaswami was himself a gifted scolder, and many people were afraid to come near him. But he said that anyone who thought he was harsh should have stood for a single second before his guru’s scolding. §

Yogaswami explained that most people try to get you to love them by giving you something you like so you will pay more attention to them; you transfer some of your attachment from the thing you like to the person who gave it to you. He told disciples, “Chellappaguru, through subtle guile, pulled me to his side by taking everything away. He did not allow me to put on any show, nor to do any service, nor to know the future, nor to have any siddhis, nor to associate with other saints or sadhus. He did not even allow me to wonder.” §