Chapter Four

Rishi from the Himalayas

What little we know of the next satguru in the Kailasa Parampara, a Natha siddha who had some 157 satgurus before him, of which 155 remain nameless, is but an oral legend. In the absence of even a name, he is called Rishi from the Himalayas, and the details of his life are tellingly sparse. There have been mystic intimations of his life and times, little more, into which the following fictive story breathes vivid detail and color, telling of India’s hoary tradition of world renunciation, self-inquiry, sitting at the feet of masters, and God Realization.§

A Boy Becomes a Sadhu

One day in a village in the North of India, the sun began to crackle on the far horizon. The villagers, soundly sleeping in their thatched huts, barely noticed, concentrating instead on clinging to the last few shreds of sleep. This day may have been like any other, were it not for one village member. Today that youthful villager would not just arise and go about his business. Today he would awaken. §

The young man slowly stretched himself in his humble cot and looked about his hut. He had prepared for this day for so long. His abode was bare; nothing of value remained—only the memories, which now seemed so faint. Yet, as he scanned the room, the travails of his life until now exerted pangs of poignancy. His eyes lost focus, revealing a memory of his mother preparing a warm breakfast for his father and him before the day’s work. Immersed in the memory, he scented the hot chapatis and fresh ghee. His mother would laugh as his father attempted to steal chapatis from the simple skillet. §

He had no family now. He might have slipped away unnoticed, except in turning around he saw nearly the whole village gathered quietly near his hut—cousins, uncles, aunts and friends he had known since his youth. There was an awkward silence. One of their sons was simply leaving to become a sadhu. Duty to his father had kept him in the village for the last year. During that time, all of the village elders knew of his inclinations and tried to steer him toward family life. In these attempts, there was no ill intent. India has known this conflict for eons. On one hand, the sadhus, swamis, yogis, mendicants, rishis and siddhas are accorded great reverence once they are established in their calling. Oddly enough (or perhaps not, given humanity’s attachments), when one chooses to tread this path, he or she usually meets great resistance and discouragement from family and community. It is a path which is supremely challenging; but for the select few who try, and even fewer who realize what is to be realized, its rewards are beyond words. §

It is traditional that a sannyasin’s past and personal history remain unknown, as the source of a river should remain a mystery. Aptly, almost nothing is known of the lone wanderer who captured the imagination of the people of Bangalore in the southern hills of India.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •§

Though his mind wavered, his soul stood firm. He smiled with affectionate detachment, brought his hands together and softly bowed toward all before him. Spontaneously, everyone raised their hands in a blessing gesture. At last, the young man turned and took his first step. He never looked back and was never seen again in his village.§

On the Road

Once alone and on the road, he strode with a determined power, halting only to rest. For days he walked along the Himalayan rivers, visiting the occasional village temple and crossing fields to keep off the roads where he knew people might be. It was a joyous time, a time of discovery of something new each day. Rising late one morning, the groggy wanderer made his way down to the river to bathe and honor the Sun. Cleansed, he performed his morning sadhanas, then continued on his southbound path. Days passed, weeks and months. §

A band of sadhus, less than a dozen, befriended him, clothed him in their simple attire and let him join in their peripatetic caravan, making their way to Palani Hills. The saints of history worshiped here; it is one of the six foremost temples in South India, called arupadaividu, dedicated to the powerful God Murugan (known as Karttikeya in North India), whose mission it is to hold the path of the realization of Siva open on the planet. He joined them full-heartedly on this long pilgrimage to see the Lord of Renunciates, his ideal in throwing down the world. §

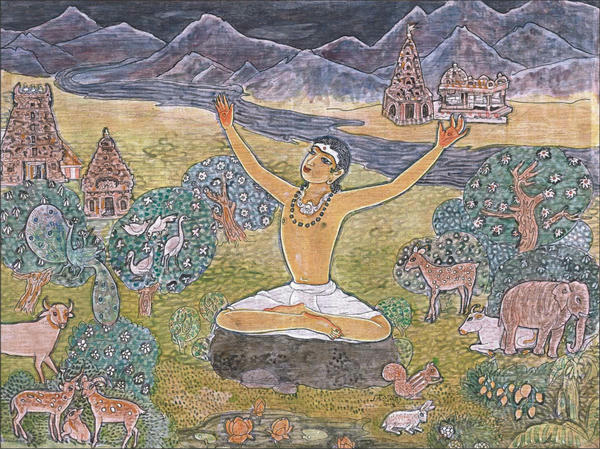

The Himalayan sadhu’s long trek to the South took him along the great rivers and through roadless forests and countryside. Each day was a joy, as he greeted Lord Siva and performed his daily sadhanas.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •§

So much happened as he drew closer to his traveling brothers, learning of their ways, their secrets, their view of life and life’s beyond. From them he learned to use a neti pot, to heal himself with herbs from the forest, to bathe using nothing but sand, to eat from the land, to use pranayama in a hundred ways, to see the perfection of the world that ordinary people miss or dismiss. He found it easy to see God in everyone he met, and his love for God Siva was deepened each day in their presence. They saw in him themselves, but younger, and they appreciated his eagerness, his gentleness, curiosity and quiet profundity. He had an uncanny stillness during their long nighttime meditations, something they silently envied. They learned much from the novice, for he was well schooled in the ancient philosophies, articulate and capable of holding his own in their nightly debates around the campfire. They found him to be something of a prodigy, and they enjoyed ganging up on him, their combined skills and knowledge being roughly equal to his own. He never noticed the ploy, lost as he was in the spiritual joy of it all. He was living his dream. He was a sadhu among sadhus, and what could be more wonderful than that? §

Weeks turned to months as the ragged band made its way, ten to fifteen kilometers a day, depending on conditions, toward their destination, the legendary Palani Hills Temple in Tamil Nadu, some 2,500 kilometers from the sadhu’s village. Even today, Palani Hills Temple is one of the most popular in all of India, so much so it is the second richest temple in a nation that boasts hundreds of thousands of temples. §

The group picked up its pace as it grew closer and closer to the temple. Pilgrims were converging on the well-used road, walking, many in bare feet to intensify their journey to God, in clusters past ragi, red chili and cotton fields on either side, threading their way through flocks of geese and herds of goats, all using the same road. Many groups of pilgrims dressed alike and sang and chanted in unison. This was not, for them, a solitary journey, but a fellowship and a sharing, a spiritual family united on the same holy trek. §

Not all were skilled musicians, but each was inspired and sang fervently in praise of (and in petition to) Dandayuthapani, the Lord they sought—the beautiful youth wearing but a loincloth, his head shaven, carrying the staff of the renunciate, the radiant and eternal bachelor, tutelary Deity of the Tamil land, the second son of Lord Siva. One devotee among the band led an hour-long bhajan of only two words. He bellowed “Haro! Hara!” and all would respond “Haro! Hara!”—some feebly, for their real work was the walking. Passing them, the sadhus joined in the choir, still hearing the incantations when they were half a mile ahead. §

The thicker the flow of pilgrims became, the more their strides filled with enthusiasm. Finally, the towers of the temple, set atop a 500-foot-high outcropping, could be seen. Lord Murugan was calling them to His feet, and they were answering His call. The sun was setting as they entered Palani, the town that hugs the bottom of the twin hills. The exhausted mendicants quickly found shelter at one of the many sadhu ashrams. They would climb to the top tomorrow. It was time now to rest and rejoice. §

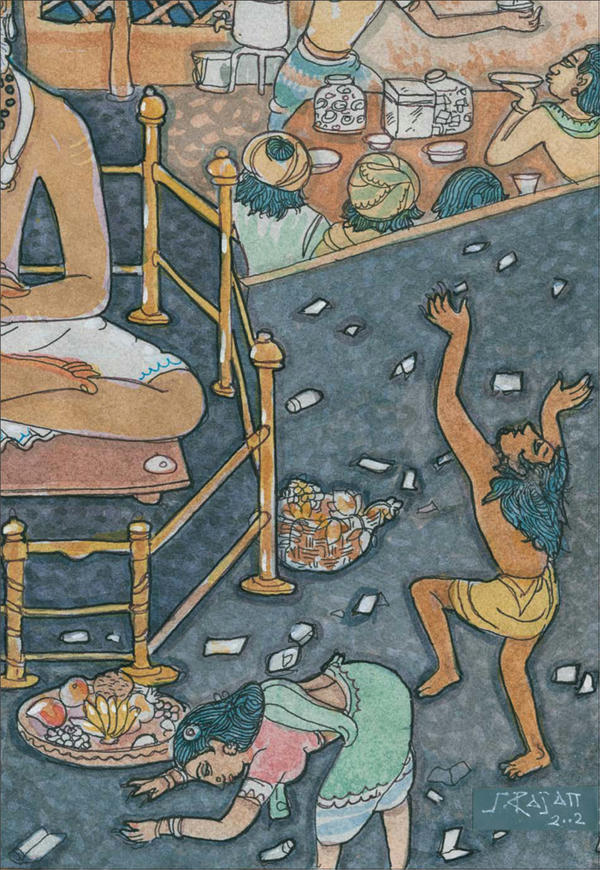

Rishi’s adventures on the road included many village encounters. In one story, he was accused by a food vendor of purloining a dosai and escaped an angry crowd who came to her aid.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •§

Awash in Inner Light

Our young sadhu arose sharply in the morning, just before the first crack of light, for pilgrims know the importance of taking the climb in the cool morning hours before the sun makes it arduous. It’s hard enough when the air is pleasant. He peered at all the pilgrims still sound asleep.§

Pulling himself to his feet and donning a fresh veshti, he bathed at the open well, bringing up buckets of water to splash over his body, water that was bracingly cool and helped drive the sleep from his mind. He was not the first up, so he was able to follow others through the small township to the gate that stood at the bottom of the hill and betokened the beginning of the ascent he had so longed for. He paused in silent thanks, grateful to be here, to be safe and healthy and able to make this climb. Then he was off, determined, as he had heard was the ideal, to not stop en route, a rigorous approach to a challenging climb. But he was young and would do it. §

He walked up the 659 steps, many carved crudely into the rock hill, worn by the bare feet of millions of earlier pilgrims. Finally, the top. Breathless, he stopped and scanned the immensity below. He could see in every direction—a view he had never had, a view of the villages and homes, the fields and roads that circumnavigate Murugan’s home, a view of a thousand morning fires with their promise of breakfast, and of thousands of pilgrims just arriving, as he had the night before. He turned, walked thrice around the temple and entered for the first puja of the day. §

After worshiping, he found his way to the cave shrine of Bhogar Rishi, the temple founder and disciple of Tirumular’s disciple Kalangi. It was Bhogar, the great siddha, alchemist and healer—some say he was Chinese—who first worshiped Lord Murugan here around the year 200 bce and who magically fashioned with his own hands a 43-inch tall icon that still stands in the modern-day temple sanctum. He did not make it of stone or metal, but combined nine poisons, nava-bhashana, with various herbs to form a rock-like amalgam which cannot, even today, be precisely replicated, though master craftsmen made repairs to the aged icon in 2006 using approximated formulas. §

Bhogar’s shrine holds a power that gives credence to the local story that he is still alive and, impossibly old, living in a cave within the mountain. True or not, the young man felt the vibrant energy of the place and found a quiet corner where he sat down. §

He was completely empty: no doubts and no expectations. No past, no future. Only the now. Effortlessly, he dove into deep meditation. His breath slowed, then virtually stopped; his awareness turned in upon itself and was soon washed in pure light, pure energy and a stillness that held the cosmos. He was everywhere and everything, infinitely expansive, without limit or body. While he was in that state, Murugan, the great God of the Pleiades, appeared in the form of a resplendent light. The light was so brilliant that he could not hold it as a vision and had to let himself be absorbed by it. He and Lord Murugan were one. He sat there transfixed as the kundalini soared upward, bringing him to a state beyond light. §

He remained in that samadhi for some time. Finally, he became aware of the light once again, then beheld another vision in which Lord Murugan revealed to him the complete unfoldment of his life. Everything from past lives to his future life was suddenly known to the young sadhu. Once the revelation faded, he sat like a sponge, absorbing every drop of its energy. Completely satisfied, he got up and, without looking around, walked down the hill and went on his way. §

Tremulous, the yogi felt remade, as if he had been given new life. After this rapturous encounter, he moved from one experience to another as in a dance. Life’s energies flowed gracefully through him. His timing was perfect. Everything he needed came to him without effort. Food appeared when he was hungry. There would be someone on the way just standing there with food or beckoning him to their home for a meal. Shelter came. There would always be a fellow seeker’s hut or a temple devasthanam awaiting him at the end of the day. After an evening meal, a mat would be offered for him to stay the night. He never thought, “Is this the way or is that the way?” He simply went here and there, following orders from within. His vision of the Lord and the kundalini experience was so vivid that he did not even need to think about it; it lived within him constantly. §

In mystic Bharat people sense when a soul has attained spiritual maturity and renounced the world, and they seek some shared blessings from him for their own journey to moksha. Intuiting that he is on a mission, they part to let him pass, cautious never to re-involve him in the things of the world. They take care of him, offering what he needs without engaging him in idle conversation. They prepare him food and let him eat it alone in respect for his chosen solitude. So it was with this young sadhu. Villagers would offer him a place to sleep and take care to not let their householder life intrude upon him. In such a culture, like a knife cutting through water, the nameless sadhu walked his path alone and unhindered. §

The Sadhu Meets His Guru

A year after his first samadhi, having trekked northward from Palani Hills, he arrived at a small temple high in the Himalayan mountains. He sat down to rest. Sensing that he was at the end of his journey, he went into deep contemplation of the beyond of the beyond. The intense vibration he had felt since his vision of God Murugan subsided into Saravanabhava bliss. Now it was as if he had finished everything, as though he were not, and yet as if he were the core of Being itself. He basked in the ocean of peace that engulfed him. §

When he opened his eyes, he saw an old man sitting across from him who seemed to be in the same blissful state. The young sadhu stayed with him, sitting and waiting. For three or four days he waited for the man to move or speak. After a few more days, he stopped waiting and wondering. Soon he became absorbed within the Oneness and peace and lost all consciousness of being in a particular place. In that silent communion he received all the teachings he would ever need for moksha in this life. They came to him in an orderly way. For days he sat there absorbing and assimilating the silently eloquent shakti emanating from the old man. §

The old man was taken care of by his devotees from neighboring villages and by pilgrims who came to worship at this small temple. They attended equally to the needs of the young man, distantly aware of the guru’s protection of the profound experiences his shishya was going through. They were together in those mountainous regions for years. Most days were spent in meditation, not talking, not doing anything, immersed, absorbed in the bliss that is the aftermath of the great non-experience of Absolute Reality. §

The young sadhu finally spoke out certain concerns to his silent guru, though not expecting a verbal response. He told of a spiritual need he had cognized during earlier days in the South. The sadhu implored his master’s grace, explaining in the wee hours of the morning that things had gone awry there and the Saiva Siddhanta teachings were no longer correctly understood. Someone was needed to reestablish the pure monistic Saiva Siddhanta philosophy, which emphasizes worship and affirms that God and man are one, that jiva, in truth, is Siva. §

One day, after a long meditation, the guru, who had barely looked at his disciple for many years, opened his eyes and smiled. They were pure and clear and luminous beyond description. The sadhu saw in them the same resplendence he had seen in the eyes of Lord Murugan at Palani Hills Temple many years before. He understood at that moment his guru’s unspoken directive and turned to be on his way. He did not wait one minute, not a second. The next phase of his life had begun. §

By the time he stepped again on South Indian soil, the sadhu from the Himalayas was an old man, a white-haired rishi. No one ever knew his name, or if he had one, so people called him Rishi. Only the barest facts have come down about him—that he was a sannyasin from the North and was probably born around 1790. He once told his one known disciple, Kadaitswami, that he had lived in the Himalayas all his life and that his guru sent him to the South on a mission. Once there, he wandered from village to village for nearly ten years, nameless and homeless, unknown and unnoticed. §

A Teashop in Bangalore

Around 1850 Rishi began to frequent a small village near Bangalore, returning to beg from the houses often enough to become a familiar sight. He may have been drawn to the Natha mystics who lived in Karnataka state, and felt an affinity with their ways. Like them, he was not your everyday yogi. Always barefoot and empty-handed, he carried no bowl, no staff, no water pot or shawl. He ate once a day, from one house, and only what his two hands could hold. Many had thought of approaching him for blessings or asking him who he was, but Rishi came and went like the wind and did not brook intrusions or the curious. He appeared out of doorways and disappeared just as quickly. He stepped out of the crowd in the marketplace, and before you could catch him he walked around a corner or into a shop and was gone. Where Rishi came from, where he stayed, no one in the village knew. No one had been able to talk to him about such things. §

He was described as a man of medium height with a thin, wiry build, intensely active and always in motion. He never strolled or ambled the roads; he marched wherever he was going, strong and straight despite his age. He wore a kavi dhoti (the rusty orange hand-spun, hand-woven, cotton garb of the Hindu saint) and two rudraksha malas, nothing more. His beard was silvery grey, his hair still quite dark, matted and piled in a crown above his head. His eyes, though, are what men remembered most about him—like two dark pools they were, large and round, black as coals and full of fire. They say he was an unusually quiet man, with an aura of unbridled power, like a river at its mouth, like the air before a storm. That heat, that current, was overwhelming, making it hard to be near him for long. §

A man named Prasad owned a tea shop in the village, located right off the market square. It was a solid building with concrete walls and a timber-hatch roof, and he made a modest living serving tea, sweets and buttermilk there. Business was brisk, as it is in most Indian tea shops. The rishi walked into his place one morning and sat down on a wooden bench against the back wall. Prasad looked up to see an old sadhu leaning back against the cool wall, resting from the heat outside. Even as he watched, Rishi looked once around the room, pulled his legs up under him and closed his eyes in meditation. Prasad wasn’t sure what to make of it, so he let the holy man be. In this time and place, holy men were revered, and even the most eccentric among them were held in awe, their movements unrestrained by ordinary society. §

When it came time to close the shop for the day, Rishi was still sitting there. He hadn’t moved. In fact, he didn’t seem to be breathing at all. Prasad came over. “Has he died?” he wondered. No, the body was warm. He sat by Rishi for over an hour, wondering what to do. Finally, he reluctantly locked the shop and went home, leaving Rishi inside. §

The following morning, Prasad found Rishi still in samadhi, exactly as he left him. He hadn’t stirred at all. Word got around quickly, and villagers crowded in through the day to see—standing around, staring at him and talking it over. Despite the commotion, Rishi never moved. His face was radiant, but unmoving, like a mask. §

That night Prasad again locked him inside the tea shop, and again the next morning Rishi was there, entranced, upright and unmoving. This went on for days, then weeks, then month after month. Word spread. People started coming from hundreds of kilometers away to see the silent saint. The tale grew more unbelievable each time it was told. In legends such things happened, in folk stories perhaps. Not in a little village in the hills. Not in modern times. And yet, there he was.§

The rishi didn’t eat, didn’t drink, didn’t move, didn’t breathe, as far as anyone could tell. He was like a log of wood, like a corpse, but he wasn’t dead, they knew. He was absorbed in God, in samadhi, keeping only a tenuous hold on the physical plane. §

Eventually Prasad closed his tea operation and cleared out all the rough-hewn tables and benches. He didn’t mind. His devotion filled him with the confidence that all his family’s needs would always be met, and they were. Once he made the decision to surrender himself to caring for the Rishi and managing the crowds that came every day for darshan, everything always seemed to flow smoothly. §

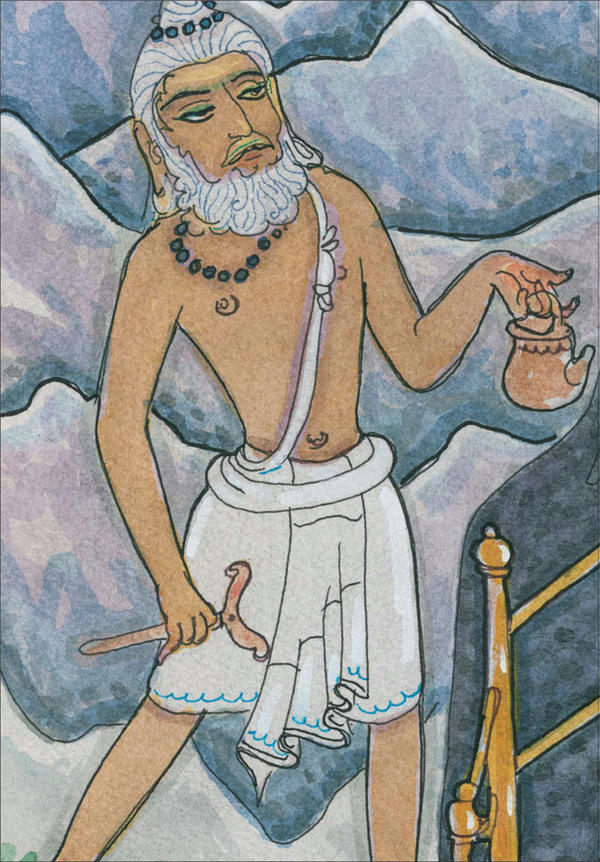

Walking the 2,200 kilometers from the Himalayas to Bangalore was not merely arduous, it could be life-threatening. It required enormous stamina, and it called forth a simplicity few could sustain. Here Rishi from the Himalayas makes the journey carrying only a water pot and yoga danda for meditation.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •§

They came from before dawn and stayed until after dark. Some were there for the mystery of it all, and others for the chance to be with philosophically astute comrades. Others were superstitious, and a few were there just to debunk the whole thing. The evenings were always busy, for there were few in the village who didn’t visit Rishi almost daily. Eventually, pilgrims from all corners of India made their way to Bangalore, to be part of history, to see something remarkable. §

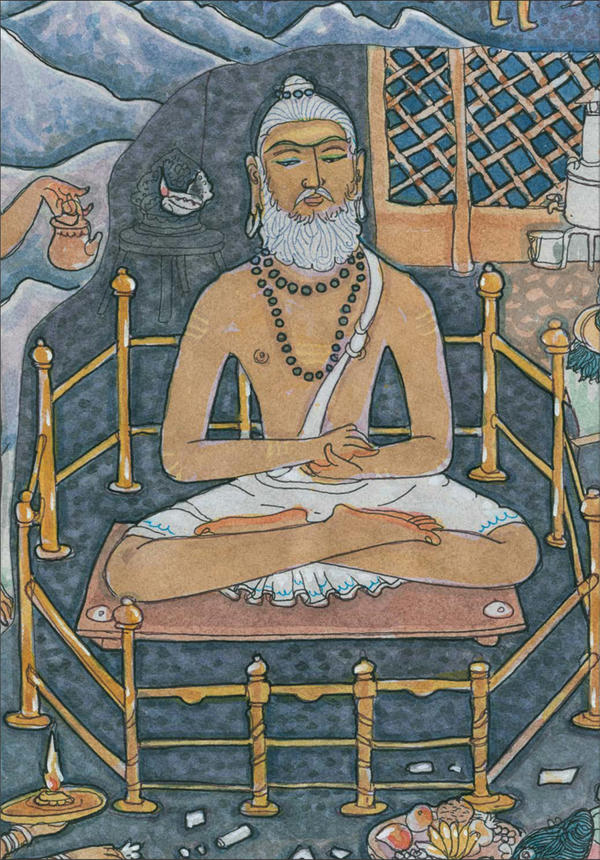

The crowds grew. It became difficult to keep them from crowding Rishi, as most wanted to touch him, to touch a bit of holiness. Prasad put up a brass railing to keep them back. It worked. Only he and his sons could go beyond it, and at least one of them was on duty whenever the shop was open. §

The various offerings people brought were passed over the railing to the “priest” on duty, who spread them out on a low, copper-clad table in front of the bench where Rishi sat. Also within the railing was a row of brass oil lamps, a dozen of them, large and small, no two alike, donated by pilgrims. These were kept burning night and day. A shallow bronze pot was added later, out in front of the railing, where devotees burned great quantities of camphor. The soot from the fires soon blackened the room, especially after Prasad bricked in all the windows for security. The remaining door he bolstered with great iron hinges and bars, and he kept the key to the shop on his person at all times. §

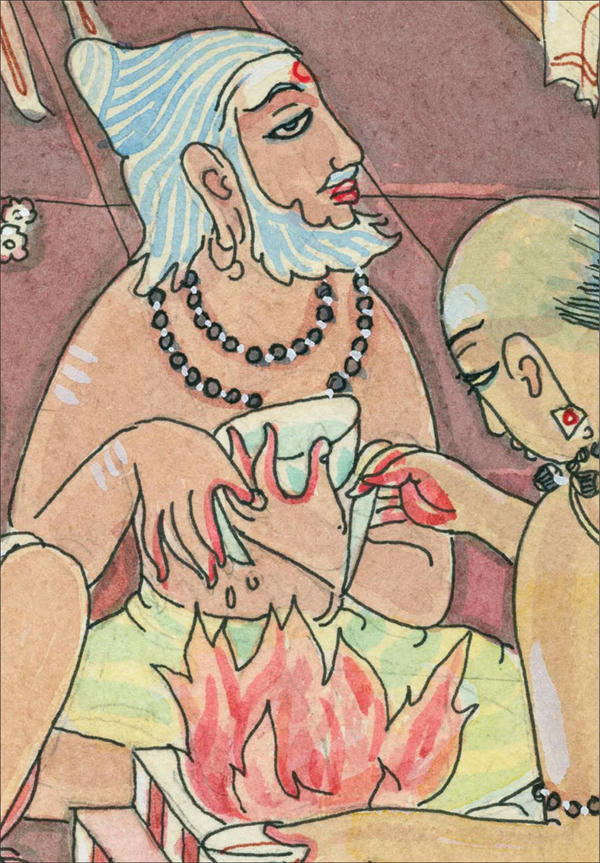

Like Starbucks today, tea shops were gathering places back in the 1800s, the traveler’s place of respite and rejuvenation. Here a shopkeeper prepares hot tea, deftly pouring the boiling brew back and forth between two cups held a meter apart to cool it to the perfect temperature.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •§

His business gone, Prasad maintained his family by taking what he needed each day from the piles of cooked food, fruits, flowers, incense and money the pilgrims brought as offerings. The rest he distributed back to the devotees as prasadam, as temples do after each puja, so little or nothing was left by nightfall. The rishi attracted an astonishing amount of wealth. No one came or went away empty-handed. §

Things eventually settled down to a routine, for there was really very little to do or see. People came to be with Rishi, staying a few hours or a few days, and then going. No pujas were done; no one chanted, sang or talked. The room was always silent, the lamps were always lit, Rishi was always there, and this went on year after year after year.§

Seven Years in Meditation

A visit to the tea shop was the experience of a lifetime, and many said once was more than enough. Stepping through the iron doorway was like stepping into another world, from the glaring heat of the Indian sun to the cool interior of a cave. One end of the room was illumined by sunlight streaming in through the open door. Only oil lamps lit the far end and the bench where Rishi sat. §

You see Rishi first, like an apparition, a wraith against the wall beyond. If chiselled in stone, he would look the same. Ringed by oil lamps, no shadows approach, so his face reflects the ruddy color of fire. He is thin and old, his ribs show through, and he is covered with a film of vibhuti, holy ash, from head to toe. No one applies it, but it is always there, powdering down on the bench and floor, the only thing about him that changes from day to day. Looking at him, the thrill in his limbs is unmistakable; it can be seen. His face is an open expression of indrawn joy, radiant and shining, mingled with the fire glow. §

On the table in front are heaps of bananas and mangoes, rice and pomegranates, clay jugs, brass pots, incense and coins all spread in profusion on a gorgeous cloth of red and green. The whole room is strewn with flowers. Everything looks polished and new—the railing, the lamps, the table—everything but the camphor bowl, blackened and bent. It must glow red on a busy day. New straw mats hide the earthen floor, and a few devotees are seated upon them. Prasad stands guard in the shadows, a portly figure in spotless white. §

It is perfectly quiet, perfectly still. A ringing silence fills the air and can be heard by those inwardly attuned, a sound as of a thousand vinas playing in the distance, a sound divine, the sound, some say, of the workings of the subtle nervous system, or, others claim, the sound of consciousness itself coursing through the mind, the sound that binds guru to disciple through the ages. It is a sound that many visitors have never heard till now, and it fills them with an inexpressible and familiar joy. §

The dim room smells of camphor and earth and the perfume of ripe mangoes piled on the table. It feels alive; it looks empty. Sitting on the mats with the other devotees, one suddenly feels the impact of Rishi’s presence. The skeptical mind is stunned, and it seeks a rational explanation: “He is an old man napping, nothing more. He is asleep or lost in a thought. Surely that’s all.” But for seven years? Seven years he has been here, they say, rapt in his soul, absorbed in God. Can it be believed? It boggles the imagination. The mind struggles and comes away baffled and yet changed by having been here, having been in Rishi’s scintillating presence. §

Pilgrims from all over India reached the tea shop in Bangalore, on the 3,000-foot-high Mysore Plateau. Many said they had been called there, having seen Rishi in a dream or vision. Prasad knew a thousand such stories, and delighted in telling them to whomever would listen. The pilgrims came with problems more often than not, and always they were helped; none was denied. Few would claim that Rishi had answered their prayers himself, for no one felt that kind of personality in him. He wasn’t there in that sense. And yet, things happened around him that didn’t happen elsewhere. §

Rishi from the Himalayas became a legend when he sat for seven years in a tea shop without moving. People came from far and near to witness this miracle, so many that a brass railing was installed to keep the crowds from touching him and disturbing his meditation.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •§

In Rishi’s presence the mind was so clear for some pilgrims, so calm, that answers often became self-apparent. Even problems that had gone unsolved for years dissolved in minutes before him. The answers came from within the pilgrim. For others the answers were more elusive, coming after they left his presence, even days later. A visitor would pray or merely think over his life while sitting before Rishi and then be on his way. Whatever the question or problem or need, the answer soon came, clear as a bell—in a scrap of conversation overheard on the street, in a song sung by a child skipping to school, or simply from intuition, from the inner sky. Sitting with Rishi opened the mind to its depths, and everything adjusted itself naturally. It wasn’t the answer itself but the way it hit the mind, the impact of it, that showed where it came from—it was straight to the point in a roundabout way, said but unsaid, seen but unseen, like Rishi himself. Always the answer hit the nail on the head, with stunning power, leaving no room for doubt. And that power did not diminish with time, as everyday thoughts do, but grew in certainty and clarity. §

Then there were the notes. On rare occasions, a pilgrim would receive a note, a message out of thin air, answering problems he had brought, silently, before Rishi. These notes appeared in the room where he sat, written on a scrap of paper. A rustling sound as it hit the floor was all anyone knew of where the note came from. These messages were never personal, never addressed to anyone, and didn’t answer questions specifically. Rather, they spoke in general terms, talking around the subject and usually explaining the way things were done in the old days. §

If a mother was worrying about the marriage of her daughter, the note might explain a bit about how marriage was looked at in the Vedas, what the ancients looked for in a family, why a man marries, why a woman marries, how to tell if the choice is good, and so on. Though brief, the notes were more than enough to show what was needed and why. Because they spoke to everyday problems, their content was seldom remarkable. Similar statements could be found in any Hindu scripture. Indeed, the notes occasionally quoted scripture, especially the Upanishads. But the way they were written, and the medium of the message, had a remarkable effect on the one who received it. The language of the notes was usually Kannada, though Telugu, Tamil, Hindi, Sanskrit—and even German, on one occasion—were also used. §

A widowed businessman came from Tuticorin, deep in the South of India, after finishing his career and leaving the estate in his son’s hands. Bringing no plans, no problems, no needs, he simply came to see Rishi. A note appeared while he was there, referring to the four stages of life—brahmacharya, grihastha, vanaprastha and sannyasa (student, householder, elder advisor and renunciate)—which are the natural patterns of the soul’s earthly vitality and karma. The man captured the subtle direction and entered a life of service in a nearby ashram, visiting Rishi often. §

The tea shop eventually became a shrine, as people came to see a spiritual giant of remarkable yogic powers. Those powers were nowhere more evident than in the magical way that prayers were answered in his presence. Sometimes answers fell from above on small pieces of paper.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •§

Five years after Rishi had come to the tea shop, four young men, students at the University of Berlin, arrived in the village to see him. They were all in their early twenties, all Sanskrit scholars, three of them quite competent. Like many of their generation, they were enthralled by the Vedas and Upanishads. They had even founded an ashram in Germany to spread the lofty teachings they so admired. §

These four had heard about Rishi from travelers in far away Berlin and decided to come to India to see him for themselves. If the reports were true, he was just the man they were looking for to guide them in practicing and realizing the ideals of the Upanishads. Two of them were wealthy enough to pay passage for four out of pocket, and so—their hearts aglow with dreams and plans, pinning their hopes on bringing Rishi back to the fatherland to head up their ashram—they shipped off to India. §

Landing in Bombay, they proceeded south to Bangalore and the village where Rishi sat. Because they spoke only Sanskrit, of the Indian dialects, a brahmin man accompanied them as a guide and translator. The people of the village were impressed with their sincerity and a bit surprised by their knowledge of Hinduism. They were hosted and entertained by the best of families, treated like princes and practically adopted by everyone. They would gladly have stayed on forever, if not for their comrades in Berlin and the mission they had come East to fulfill. §

Once they met Rishi, their world turned around him alone. They spent two days sitting in the tea shop, coming outside only to hear Prasad’s stories. After two weeks, each of them had their own stories to tell, of wonderful experiences, inner and outer. The rishi surpassed their wildest dreams. They were sure they had found their teacher. The future of Hinduism in Germany looked bright. They talked about it excitedly: Could Rishi be aroused? Would he even speak? Could he travel in his present state? Dare we disturb him? Most important, would he agree to go to Berlin? What if he refused? Then what? §

A message materialized one day, the kind Prasad always talked about, written in German and obviously meant for them alone. That note convinced them utterly. They were walking on air for days afterward, reciting it to each other like a hymn, like a mantra. The note was in Rishi’s usual style, indirect, talking all around the question, yet plain enough: §

“All things can be—according to karma and opportunity. A man’s karma is threefold: that which awaits a future birth, that which awaits an opportunity and that which is in motion now. Sadhana spares the least of men a thousand future lives.” §

Such profound thoughts simply had to be heard back home. For most of the next week, the four debated about how Rishi lived without food. They made plans to inquire, ending up at Prasad’s home one evening where they broached the subject for the first time, questioning him through their brahmin interpreter. §

“Does a man in samadhi ever eat?” they asked. “How long can he go without food?” “Just supposing Rishi had to be moved to a larger building someday—how would you go about it?” Prasad answered them as best he could, smiling all the while. He didn’t understand their intentions until they asked him about coming past the railing. Then he said, “No, it might disturb Rishi.” They asked again. He said no, he didn’t let anyone past the railing. The students tried another tack. One began to describe their ashram in Germany, going on at length about how much the people there needed a genuine teacher, someone like Rishi, for example. §

Prasad listened with growing horror until he got wind of a scheme involving crates, carts and steamships, when he jumped to his feet and let loose a speech that brought tears to his eyes. He talked himself hoarse in five minutes, and not a word of it got through. The brahmin man wasn’t translating; he was busy himself explaining to his clients the consequences of even thinking of such things, and they were arguing back at him. Prasad went inside and slammed the door. §

They didn’t see him again until the next morning, when they walked over to the tea shop for their daily meditation. Prasad was there, sitting in the dirt out in front, slumped against the wall, his hair disheveled, his veshti trailing, the picture of misery in the extreme. The shop was still locked. §

“What’s wrong?” they asked. “Prasad, what’s the matter?” Prasad told a tale of woe to the brahmin, who nodded his head sadly and rolled his eyes as he listened. Then he turned to the Germans and translated. “My friends, a calamity has come to us all. Not an hour ago, when Prasad opened the shop for the day, what should meet his eyes but an empty room! The rishi has vanished in the night. They have searched the town and no one can find him. He is gone. Ah! What have we done to deserve this? This is bad news, indeed.” §

Then he sat down beside Prasad and put his head in his hands. The students were skeptical. They wanted to see for themselves. “Why is the door locked if Rishi isn’t here?” Prasad didn’t hear the question. One of them stepped up and rattled the door. “Where is the key?” he demanded. In the wink of any eye, the veranda was crowded with men, a half dozen stalwarts, and the village headman was crossing the square. “What’s all the noise?” he inquired. “Can I help you?” §

Rishi was regarded variously by those who visited the tea stall: yogi, magician, oracle and Deity. No matter how they saw him, visitors approached with trepidation and reverence for the remarkable man who lived apart from ordinary consciousness.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •§

The Germans explained Prasad’s tricks. The headman was surprised. “Perhaps you have misunderstood,” he apologized. “You must permit me to explain. My friend Prasad is an honest man. I have known him many years. All of us here can vouch for him. If he said Rishi is gone, Rishi is gone. I do not think you will ever see him again.” §

The students understood exactly what was being said, and they withdrew. Too late, they realized their opportunity had gone. They lingered on in the village three days more, to no avail. The rishi was still “gone” and so was their welcome. They ate alone for the first time since coming to India. They had no callers, and no one spoke to them, even on the street, except to inquire about their travel plans. They left on the fourth day for Bombay, and they never came back. §

There were other foreign visitors to the little tea shop during the following two years, though no one ever again tried to disturb Rishi. Life went on as it always had, until one day Rishi opened his eyes and looked at everyone present. A few minutes later, he stood up, stepped out of the shop and walked down the road. He had taken great care during those years, through practice of pranayama, to maintain the flow of life through his body. So he was able to get up and move about with the merest instability, more like someone who had sat in one position for too many hours. §

Word spread quickly, as it does in small villages. Everyone came running, from the fields, from the shops, from the houses. Everyone was there. The mere fact that he could walk after seven years astounded the villagers. They didn’t want to lose their silent saint. His being there had transformed their lives; they wanted him to stay with them. They couldn’t imagine life without him, so they acted quickly. §

With everyone pooling the best that they had, a two-room cadjan hut was built that afternoon on a low hill overlooking the village, on virgin ground next to a stream. They stocked it and overstocked it with utensils and food, bedding and more. Now, should he want it, Rishi had a hermitage—remote enough for him and close enough for the villagers who had grown to love and revere him so. §

No one had seen Rishi, so the following morning men and boys fanned out and searched the countryside for miles around. They found him in the late afternoon, asleep under a tree. The village elders hurried to the spot, bearing gifts. The rishi sat up when they came and made their pranams. He was staring at them in surprise. They placed their offerings at his feet and everyone begged him to stay, talking all at once and by turns. All his needs would be met. His hermitage was ready, they told him, and if it wasn’t just right, they would build a bigger one. They assured him they were there to serve and obey him always, their children, too. “You must stay,” they pleaded, “Please don’t go.” He sat impassively and they knew enough to take their leave. §

Before daylight the next day, the village headman was awakened from his slumber by little boys shouting at his gate: “Come quick! Come and see!” They pointed to the hill. The rishi was sitting out in front of his hermitage, tending a small fire to keep away the cold that comes many nights at 1,000 meters above sea level, looking out over the village, right where they wanted him! The headman and others gathered up baskets of fruits and flowers and, walking single file, approached as Rishi looked on while adding sticks to the fire. Laying their offerings at his feet, they prostrated, then stood with folded hands, nervous and uncertain after yesterday’s encounter, not knowing how to approach this man who had been immobile all those years and now was on the move. The rishi offered no response, and, after some awkward moments, the villagers nodded one to the other and turned back to their homes, saying not a word along the way. §

In time, the courageous villagers returned to enjoy his darshan. But he was different. He absolutely refused food prepared for him. Instead, he ate a meager fare that he picked and prepared himself and shared with the crows, content to sit on the bare ground. He seemed almost crazy. He didn’t behave the way they had imagined he would. §

His eyes were so fiery and intense that people who had once so devotedly worshiped him while he was sitting in samadhi no longer felt the same rapport. In fact, they became afraid of him; such a potent spiritual presence being more than they bargained for. Some even wished the holy man gone from their lives and pondered how to be rid of him. Their fears and confusions were not unknown to Rishi. One afternoon, some of the distraught villagers went to speak with him, but found the thatched shed burnt to the ground. The rishi was gone. §

Rishi’s serenity during the silent years in the tea shop gave no indication of his fiery nature, which was experienced later. Villagers wanted him gone, but before they could engineer his departure, he torched his simple thatched hermitage and left the region forever.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •§

It was a month before the regular stream of pilgrims coming to the village showed some sign of abating. People still came to see Rishi, and the villagers found it hard to explain why he had gone away without accusing one another, but there was an unspoken agreement on all sides not to do that. The tea shop was left open at all hours, if only to convince skeptics that Rishi had ever been there at all. No one talked about his leaving, though. In the wise old way of a Hindu village, it was one of those disasters that had never happened, a thing that wasn’t talked about or thought about. Life went on. Instead, the pilgrims heard about how sublime Rishi was, how he sat in that one place for seven years, answered prayers in magical ways and never moved once until the day he got up and walked out of the village. No, no one knew where he went. No, they didn’t think he would return. At least, it didn’t seem likely. §

A few months after Rishi’s departure, a towering sadhu arrived, a huge man, two meters tall. He stood head and shoulders over everyone. Entering the village, he walked straight to the tea shop as if he’d been there before, and sat down inside to meditate. He didn’t come out for several hours. Then he started asking around about Rishi’s departure and where he had gone. Prasad told him what he knew. §

He had dinner at Prasad’s house that evening; and afterwards, rumor had it, the two of them talked in private long into the night. The townspeople thought Prasad probably gave the sadhu some information not usually shared with strangers.§

The lanky sadhu stayed for a week, and talked to just about everyone about Rishi, even going out into the fields to chat with farmers. He walked up the hill to Rishi’s place, but came right back down, saying there was nothing up there. A good part of his day was spent talking with people in this way, and the rest of it in meditation. He slept several of the nights he was there on the floor of the tea shop itself; otherwise, he could be found at Prasad’s house. Whenever he was asked his name, he would only say that he was from Rishikesh. From his accent, though, people guessed that his native tongue was Telugu, though he spoke Kannada, Tamil and English around the village. §

The opinion of most villagers was that Rishi had gone north, back to the Himalayas, but no one knew for sure; so the sadhu left the village, still not knowing where in India Rishi was. Later tales spoke of Rishi’s presence in Sri Lanka, where the miracles and the magical notes appearing from nowhere and falling to the floor occurred again. In fact, it is said that he was better accepted in Sri Lanka than in India.§