Chapter One

Seeking a Guru in Ceylon

Having saved his funds by living a frugal, almost ascetic existence, Robert Hansen, 20, boarded a steamer in February of 1947, sailing from San Francisco under the Golden Gate Bridge en route to Sri Lanka (then called Ceylon), heading the five-member American-Asian Cultural Mission. Months before, he had danced on the stage of the San Francisco Ballet Company, reveling in the joys of being their premier danseur. But the lifelong spiritual urge within him would not be subdued by worldly success, and he was determined to leave for the exotic East, there, he hoped, to find a true and authentic guru who would guide him to the Self within. §

In sharing that departure with the monks of his yoga order 25 years later, he described it as a dark, dreary day and noted the Dutch merchant marine boat, the MS Mapia, sailed with an English crew. He was free of responsibilities for the first time in years, and it was a freedom he savored. The month-long voyage was aboard a working ship with rough accommodations. Robert’s berth was the cheapest available, a tiny, one-man chamber below deck right above the engine room. This was to provide an unexpected encounter with the supranormal, which he shared aboard another ship during a 1999 Alaska travel-study cruise with 45 disciples.§

I took the first ship after the war leaving the port for Sri Lanka. It was a freighter. My cabin was right over the engine room, and that was very disturbing. I remember one time I was in deep meditation, really deep meditation, not really hearing anything. Then I came out of that silence and heard this roaring engine—rrrrrrr. I said to myself, “I wish this noise would just stop,” and it did. Immediately, the whole ship stopped. We floated for three days, going off course a little bit. They couldn’t find out what was wrong. Finally, they found that two screws had come loose in the engine. They fixed the problem and the engine started up again. It was a lucky thing because we were going through mine fields. It was just after the war. The ship could have been blown up very easily, and only toward the end of the voyage did we know what the cargo was. It was munitions. That would have been a big bang for all of us—something you would want to miss.§

Robert took to meditating in his tiny cabin, right above the engine room. Coming out of meditation one day, he was jarred by the giant engine’s piercing noises. He mentally called for the noise to stop, and the engines halted for days.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •§

In a later recounting, he reflected on how this experience impressed on him the power of the meditative mind, a power that was unleashed spontaneously that day on the ship. §

The cultural troupe practiced on the wooden deck of the moving ship and built a small pool in which they could splash around on hot days. They shared meals with the crew, even the captain. The captain took his gallant young passenger to the wheel room one day and told Robert, “See that pen on the table? If I even pick it up, I relinquish my job as captain.” Robert would recall this later in life when describing his duties as a guru. §

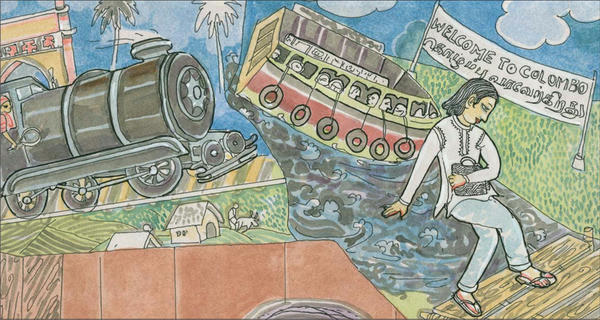

The troupe disembarked in Bombay on March 8, but as their Indian visas designated them as “through passengers,” they stayed just a few days before boarding a train for the South of India. From Madras, they took a ferry across the narrow Palk Strait to Talaimannar on the Western side of Ceylon. Boarding another train, they reached Colombo in mid-March of 1947. On March 23, Robert wrote from his new home on Galle Road:§

Ceylon is much better than our hear-say before arrival; if you hear anything good about this country, double it and you’ll have the truth. It truly is the garden spot of the world. The people are alert, strong, wide awake, healthy and desirous of modernizing their country in every way.§

Ceylon is nothing like India. The day after my arrival some friends, a Sinhalese man and his wife and driver, took me up to Kandy. You should have been there. We went to the Temple of the Tooth and the old Kandy palace which is in ruins now. Everywhere you look, all over the Island, you see nothing but green trees all year around. People plowing with elephants, and by hand. The men wear sarongs or pants; the ladies wear saris. In Kandy they dress in a different way. A man is walking by with a box balanced on his head—that’s the way people carry things here.§

There are several boys that take care of the house—every time you pass they come out with a big “Hello, sir.” It’s about all the English they know. They are so polite they always say yes to everything, whether they understand or not. §

We thought it would be very hot, but it’s not at all; and rather cool at night, and though this is their hot season, I can still wear a wool sport coat and not sweat too badly. We have to keep everything under lock and key, because we are not living in an age of saints, though Ceylon and India are both very spiritual countries. They respect people a lot who don’t eat meat, take coffee or tea or drink or smoke, so I have won many fine friends, and being universally minded, can mix with any type of people, class or faith, which is a big advantage.§

From Bombay, Robert traveled south by train to Tamil Nadu, then took a ferry across Palk Strait to Colombo, Ceylon, his destination.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •§

On Saturday my friends and I (Mar 29) were going up to Adam’s Peak, about 6,000 feet above sea level (it’s very cold there) to see the sunrise on Sunday morning. Every full moon people of all beliefs go there and shout, “LOVE TO ALL! LOVE TO ALL!” whether they are Buddhist, Hindu, Mohammedan or Christian, rich or poor.§

You see many strange and wonderful things, such as snake charmers, fortune tellers that can tell from old Sanskrit records just how many in your family and describe them all to a T, and all your past and future. The records are thousands of years old and take a long time to read. Elephants walking down the street, bargaining, new tongues, beautiful sunsets. Tea at 3:30 pm. Driving on the other side of the street makes it hard for US pedestrians. Love to all—write soon. Bob§

Robert’s journey to Lanka was choreographed by his early catalysts. In fact, his first teacher, Grace Burroughs, received him when he reached Colombo, welcomed him to her dance studio there and saw to his well-being for the first year of his stay.§

Meeting His Mentor’s Challenges

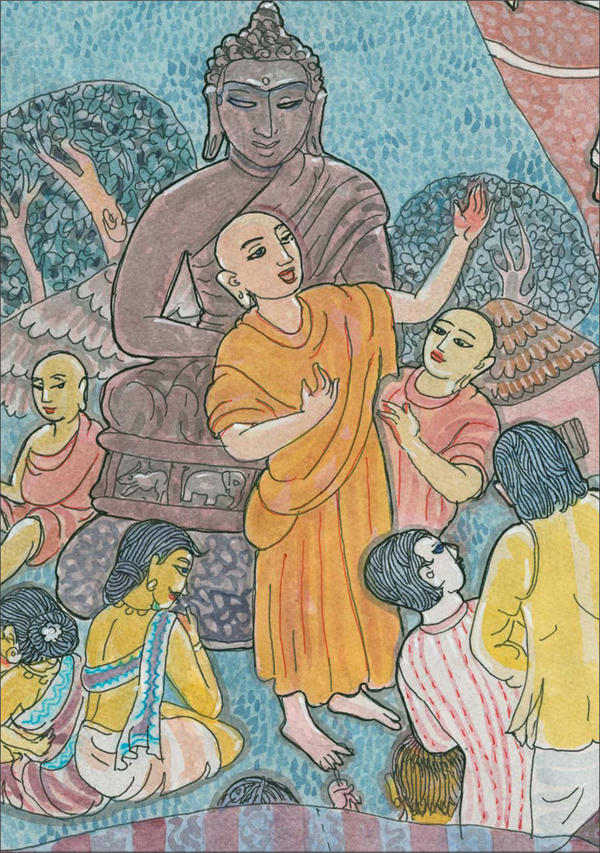

In Ceylon, he studied with his fourth catalyst on the path, Dayananda Priyadasi (Darrel Peiris), a Sinhalese Buddhist who, during his first visit to the US in 1934, had established an ashram at the Oakland home of Robert’s second catalyst, Mother Christney. Dayananda was a dynamic teacher of meditation and occultism and a great patriot of this island nation. §

Ceylon was then in the final stages of 21 years of active struggle for independence from Great Britain, which it gained in 1948. The times were unsettled; and the fiftyish Dayananda, who was both meditative mystic and charismatic politician, took advantage of the situation to train his new protege personally in the art of getting positive things done in the world. Within months of his arrival, Robert helped found two schools for village children, assisted in reviving the dormant Kandyan dance and introduced electric power saws to carpenters, who had never seen such contraptions. These down-to-earth projects were a part of his training.§

I was happy and awed to meet my fourth catalyst on the island of Sri Lanka, a Buddhist. He was a strong, active Sinhalese man dedicated to spiritual awakening and bringing this through in a vitally helpful way to all of humanity. He had been high in Ceylonese government and was practical and forceful as a teacher. I studied with him for one year and a half.§

In earlier years, Dayananda attained enlightenment in a cave in Thailand by sitting in the morning, eyes fixed upon the sun, following its travel across the sky all day long until it set at night. He practiced under his guru this most difficult sadhana. Then one night while meditating in a cave, the cave turned to brilliant light, and a great being appeared to him, giving him his mission and instructions for his service to the world.§

My fourth catalyst taught me how to use the willpower, how to get things done in the material world. He was a real father to me. I needed this at twenty-one years of age. I wanted to meditate, but he wanted me to work to help the village people in reconstructing the rural areas. He assigned me to do different duties, sometimes several at a time, which I had to work out from within myself. One was seeing that a new village bridge was put up that had been washed out in a flood, bringing into another village modern saws and carpentry equipment to replace traditional tools used in building furniture.§

I had to take a survey of all the carpenters using handsaws on the west coast of Sri Lanka. I went around with a notebook and listed all their names and addresses and the types of saws they were using, for my assignment was to see that they all would eventually be provided with electric saws. Getting modern equipment into the Moratuwa area was one of the biggest assignments I had ever had, and I had no idea how to begin, for I had never done anything of this nature in my life. Occasionally my catalyst would ask, “Well, have they gotten their saws yet?” All I could say was, “Well, I’m working on it.” §

His mentor, Dayananda, was a Buddhist mystic, politician and social activist who engaged Robert in a difficult project—introducing the electric circular saw to the village carpenters of Ceylon who were using simple hand saws.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •§

Executing governmental changes was strange to me. My life had been quiet, with no exposure to methods of business. But even worse, I was in a foreign country that had different customs, subtle ways of relating and suggesting. Most of the educated could speak English beautifully. In the villages, however, only the native languages, Sinhalese and Tamil, were spoken and understood. The craftsmen were accustomed to the old ways, their fathers’ ways, of making furniture, and were not easily persuaded that electric saws would improve their work. Some had grown up in remote regions where there was no electricity, no running water. So naturally they resisted such a massive change. They made good, sturdy furniture already. Why complicate life further, they must have thought.§

My natural shyness was the biggest barrier though. I had to interview people, do research and convince people of the practicality of electric equipment. Finally, it unfolded to me from the inside how to go about it. I drew up an elaborate proposal, long and wordy, with myriad details, diagrams, names and addresses. I gave it to him. He was pleased and said, “Now what I want you to do is take this fine proposal to the head of the Department of Rural Reconstruction. You give it to him, and I will do the rest. But while you are in his office, sit down with him and tell him how fast work is done in your country by using modern equipment to make furniture.”§

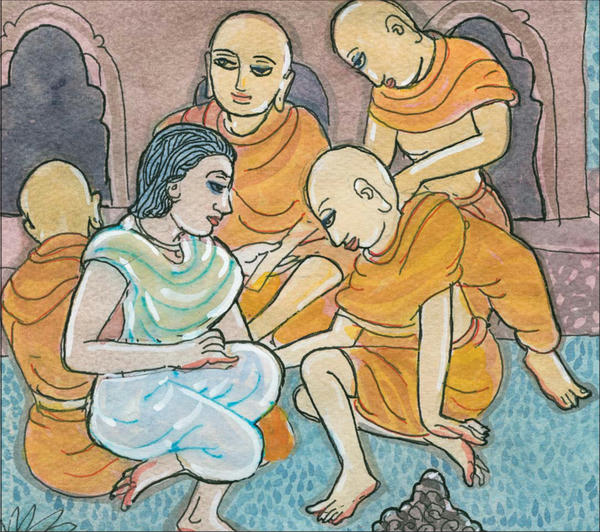

Robert lived as a guest in Buddhist temples and monasteries, conversing with the monks, observing and absorbing their strict lifestyle, ways of life he would later implement in his own monasteries.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •§

I was happy. At last I had something definite to do that would bring this project to a successful end. I went into Colombo to the Office of Rural Reconstruction and presented the proposal. The government was convinced, and not many months later the modern electric saw became available and popular in the Moratuwa villages for any carpenter who needed one. Sri Lanka had just that year received its independent dominion status from the Crown, and there was a lot to do to bring the rural areas up to better standards. I did my part in the best way I knew how and was glad to do it.§

One assignment like this after another was given to me. This fourth catalyst of mine worked on the philosophy that you do what you’re told. If you are given an assignment, do it to perfection. Finish it. And don’t come back with excuses. If he sent you on a mission, you wouldn’t dare return until you had completed that mission, not to your satisfaction but to his. He might have nothing more to do with you if you failed. I knew that, so I was very, very careful. Inside myself, as I struggled to do tasks that seemed impossible, I could hear him saying, “Don’t fail, don’t fall short. You create the obstacles. You can overcome anything, do anything, be anything.” He challenged me to work problems out from within myself, offering little advice and often assigning a task and then just leaving. §

He was quick to point out my mistakes, even though he knew I was sensitive and couldn’t stand being scolded. Still, he scolded and criticized harshly. This was good for me, and I am still thankful for his direct and powerful ways. He made me use my own inner intelligence to complete each assignment, and most of them were of a worldly nature. At this time in my life that is exactly what I needed, to strengthen the outer shell, to learn to accomplish duties in the world. It was invaluable in later years.§

Dayananda had me meditate in the villages. I would sit in the lotus position for an hour or two while he talked to the village people about meditation, bhavana. They were all Buddhists. They appreciated the Buddha’s philosophy but did not meditate. So, together we would go from village to village encouraging the people to meditate, to put the enlightened teachings into practice. Finally I was getting my own meditating done while he was teaching the people and the Buddhist priests about it.§

Dayananda campaigned constantly in rural villages. One day he showed the American visitor his powers, closing his eyes and entering the mind of a speaker on the stage, who suddenly began talking about a subject Dayananda and Robert had shared earlier that day.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •§

Prior to my arrival in Sri Lanka, Dayananda had worked with Thailand’s Buddhist priests to build a wonderful school of meditation that served to uplift the Thai people. Because of his efforts, many priests now meditate in Thailand, as do the lay people of the country.§

Every once in a while I remarked, “I want to go into a cave and meditate. I want to realize the Self.” He said, “Plenty of time for that. You can go into a cave and meditate after you have finished the next two or three assignments. Anyway, the cave is inside of you.” So, I continued with the assignments month after month. §

From time to time I reminded him, “You know, I came to Sri Lanka to find my guru.” It had been impressed on me by my teacher in California that this would happen in Sri Lanka but that I should have total realization of the Self first. So, I had come to Sri Lanka to meditate to realize the Self and to find my guru. Yet, here I was in governmental agencies and wandering around in the villages. I deeply felt that if I could get away from doing external things and go into a cave, which is traditionally the ideal place to meditate, I really could realize the Self. In fact, I was sure of it. If he would just give me a little time off. But would he? No.§

I confess, I rebelled. Inwardly I criticized this incessant concern about business and social change. After all, I thought, he is not my guru, and I am not here to change the world. I’m here to meditate. Maybe I should just go off to a cave without telling him. The rebellion externalized my awareness. Suddenly it was more difficult to do the assignments. I was too preoccupied, divided between what I wanted personally and what my teacher wanted me to do. I struggled for a while, but then conquered this rebellion within a week and never allowed it to occur again. The biggest enemy on the path is a rebellious nature, wanting to do things our own personal way, being inflexible and unable to give up our own will for a greater purpose. I settled down to obey him exactly and directly, becoming an even more positive person. I was a very positive person at that time, and remain so today.§

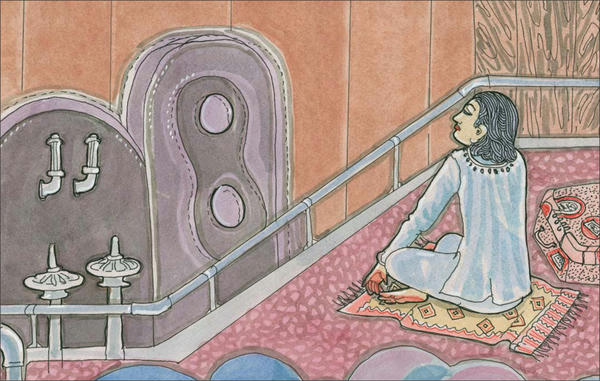

I visited and lived in many Buddhist temples in Sri Lanka. I was received by the monks there. I saw how they lived, saw how they dressed, and that influenced in a very strict way the monastic protocols that we later put into action in our own monastic order.§

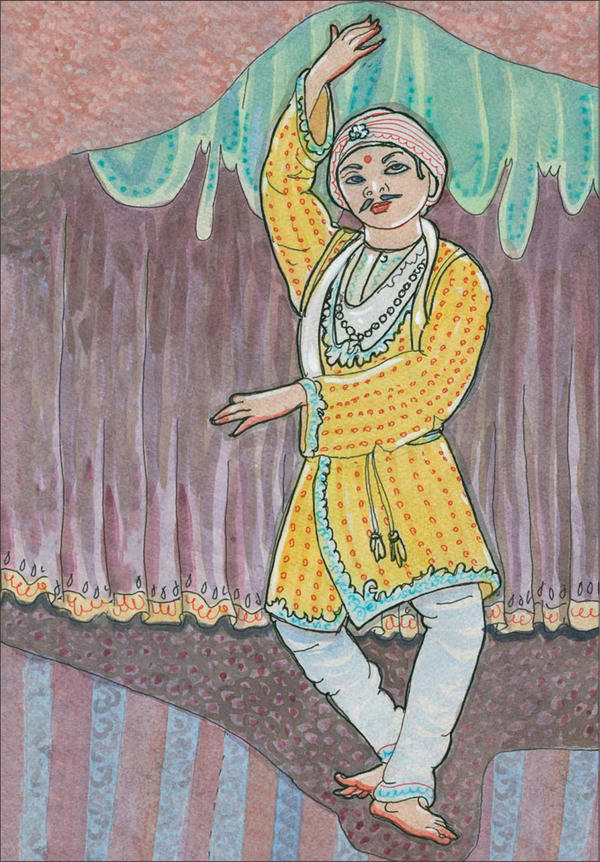

Led by young Robert Hansen, the American-Asian Cultural Mission toured Ceylon for months, dancing in every important venue, with the goal of bringing East and West together through dance and music.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •§

Dayananda was campaigning incessantly on the road, taking his protege from village to village. He aspired to be the head of the country, and many thought he would be, though it never happened. He once took Robert to a Buddhist home where they lived for three days. The teacher took the opportunity to stretch the young American’s discipline, and demanded that he meditate through the night, without respite. §

Dayananda was a skillful speaker and would often hold forth from a makeshift stage or under a tree, his American executive secretary standing nearby. One day, in a remote village, they were standing together as the local chieftain was speaking words of introduction, working the crowd for Dayananda’s speech. Almost playfully, he turned to Robert and said, “Watch this.” Dayananda closed his eyes, his concentration etched on his brow. Within a minute, the speaker completely changed subjects, talking of things that Dayananda and Robert had shared earlier. Robert soon realized that Dayananda had gone within himself and entered the man’s mind, and was in fact speaking through him. It was a demonstration of white magic that he never forgot. Impressive, he would later say, but not all that useful. Dayananda was full of such magic-making, something Robert would later regard as an obstacle to spiritual unfoldment, not a demonstration of it.§

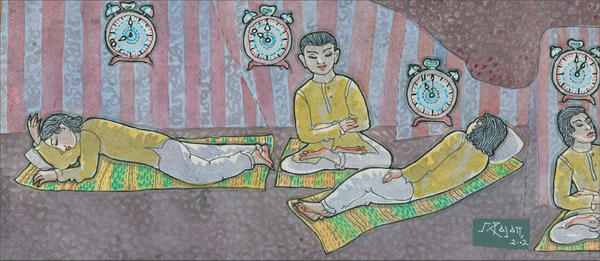

At one point Dayananda gave his young charge a wind-up clock and instructed him to follow a Buddhist meditation practice. Robert was to set his clock to wake him in two hours. When the alarm went off, he was to sit in lotus posture and meditate for a time as deeply as he could. Then he would reset the clock, lie down on the floor and sleep, waking in two hours to meditate again. Throughout the night, day after day, he followed this discipline, meant to bring the consciousness of meditation into other states of mind. §

While working with Dayananda, Robert remained busy with the travels of the cultural troupe. They traveled north and south, performing at the nation’s formal musical and dance halls, in small towns and on college stages. They raised funds for the Child Protection Society at Royal College Hall in Colombo and mesmerized the crowd at Bishops College on July 23, 1947, where the reviewer noted, “Robert Hansen again proved himself a clever ballet and character dancer.” He worked his body hard, and drank so much hot water to purify himself that the Sinhalese called him Unu Wathura, which means “hot water” in that language.§

One of the spiritual disciplines given to the young American was a sleep sadhana. He was required to rise every two hours throughout the night to meditate.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •§

From the Town Hall in Kalutara to Wales College Hall in Moratuwa to the Young Men’s Buddhist Association, they brought their dynamic fusion of East and West song and dance to audiences who had never seen such performances, let alone the Matchless Muchachos and the acrobatic tango during Latin American Night at the Silver Fawn Club.§

Dance took great effort, with all that travel, yet Robert managed to squeeze in another of his loves: organizing. Again and again, the newspapers reported on his efforts to bring the people of Ceylon together for good causes. He formed the World Fellowship of Youth on March 20, 1948, and soon established the World Fellowship of Artistes, which grew into the Opera and Ballet Guild of Ceylon, established on July 23. §

Robert was about to embark on his greatest challenge, the struggle to realize Parasiva, the Self within all. Every experience in life had led him to this moment, a moment that would transform the young American into an enlightened being who would one day transform and guide Hinduism in the United States and beyond. To understand the experience he would soon have in the deep southern jungles of Ceylon, and the spiritual tradition he had discovered, it is necessary to go back in time, to the Himalayan mountains and the mystical sages who first charted the path Robert now found himself on.§