IXTY PERCENT OF ASIAN INDIAN adults in the united States are married. The specific phenomenon I am interested in examining is how middle to upper class Indian-American Hindu men and women negotiate the Hindu wedding ritual, including the marriage decision process. This book begins with the second generation’s process of finding a spouse. It moves through the engagement process, and concludes on the wedding day. Although the focus here is negotiating engagement and marriage, I am interested more broadly in the negotiation of culture. Whereas originally I situated second-generation Indian-American Hindus between two antithetical philosophies—that of prototypical mainstream middle-class America and traditional India—my research repeatedly frustrated this worthy assumption, prompting me to extend and complicate my thesis to include modern-day Bollywood as a prominent mediating source of culture informing second-generation Indian-American Hindus on their wedding day.§

IXTY PERCENT OF ASIAN INDIAN adults in the united States are married. The specific phenomenon I am interested in examining is how middle to upper class Indian-American Hindu men and women negotiate the Hindu wedding ritual, including the marriage decision process. This book begins with the second generation’s process of finding a spouse. It moves through the engagement process, and concludes on the wedding day. Although the focus here is negotiating engagement and marriage, I am interested more broadly in the negotiation of culture. Whereas originally I situated second-generation Indian-American Hindus between two antithetical philosophies—that of prototypical mainstream middle-class America and traditional India—my research repeatedly frustrated this worthy assumption, prompting me to extend and complicate my thesis to include modern-day Bollywood as a prominent mediating source of culture informing second-generation Indian-American Hindus on their wedding day.§

Not two but three cultures are operating in the lives of second-generation Indian-American Hindus when they are planning their weddings: 1) a traditional India which in some respects no longer exists in the most pluralistic country in the world but which has a presence in the immigrant and second generation’s memories and sense of history, 2) mainstream middle-to-upper class America as described in wedding planning magazines such as Modern Bride and websites such as theknot.com, 3) and Bollywood India as instantiated by wedding-planning magazines such as Bibi and websites such as benzerworld.com.§

Weddings are a window into seeing how second-generation Indian-American Hindus construct India and America. Weddings reveal conflicts and choices. Finally, weddings matter, not only for the bride and groom. Weddings are rites of passage where intergenerational and cross-cultural tensions play out and, in the case of Indian-American Hindus, convey a sense of compromise between multiple cultures.§

3. The Boy’s Character

HE GIRL’S PARENTS REGARD THE BOY’S education and earning ability to be of vital importance, for these make likely his long-term financial stability. It is also highly desirable that he already be employed. Once satisfied with the boy’s ability to adequately provide for a family, his personal character reputation among friends, relatives and teachers is carefully looked into. Male relatives of the girl will talk with this group of people, inquiring in some detail about the boy, his personal habits, religiousness, reliability and how he behaves with regard to girls. If the boy lives in a Western country, this latter issue would be investigated quite carefully. Health is very important. There should be no indication of mental retardation, schizophrenia, or disease such as TB. Drinking or smoking can be a very negative attribute. Physique is only critically important in that the boy must be taller than the girl; otherwise it is a useful but not determining factor. Parents will also look closely at the boy’s father and grandfather, on the assumption that the boy will develop the same good (or bad) qualities. Similarity of boy and girl is the goal. For example, parents would not marry a refined girl to a boy who is crude or uneducated, even if well-employed.§

HE GIRL’S PARENTS REGARD THE BOY’S education and earning ability to be of vital importance, for these make likely his long-term financial stability. It is also highly desirable that he already be employed. Once satisfied with the boy’s ability to adequately provide for a family, his personal character reputation among friends, relatives and teachers is carefully looked into. Male relatives of the girl will talk with this group of people, inquiring in some detail about the boy, his personal habits, religiousness, reliability and how he behaves with regard to girls. If the boy lives in a Western country, this latter issue would be investigated quite carefully. Health is very important. There should be no indication of mental retardation, schizophrenia, or disease such as TB. Drinking or smoking can be a very negative attribute. Physique is only critically important in that the boy must be taller than the girl; otherwise it is a useful but not determining factor. Parents will also look closely at the boy’s father and grandfather, on the assumption that the boy will develop the same good (or bad) qualities. Similarity of boy and girl is the goal. For example, parents would not marry a refined girl to a boy who is crude or uneducated, even if well-employed.§

RAJEEV N.T.§

While his family structure may be readily apparent, the boy’s individual achievements and qualities come under the microscope. His current career position offers a glimpse into his capabilities and potential.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •§

A Match that Was Not to Be: Rati and Paul

For Rati, a defining moment in her search for an Indian-American Hindu husband was when her white boyfriend accused her of “being racist.” Rati had just returned from her first trip to India since she was a child. She stayed in the houses of various relatives, family with whom she “picked up from when we last met without skipping a beat.” Often she was meeting extended family for the first time and was impressed by the open-armed welcomes. Upon returning from her trip to her home in New York, Rati’s interests in Indian culture reignited. She revived her love for vegetarian dishes and began taking yoga. Along with continuing her bharatanatyam (classical Indian dance) classes and watching Bollywood films, she began attending the local temple with some international Indian students she met at the local art theater’s showing of Lagan, a popular Bollywood film. Paul, Rati’s boyfriend at the time, quietly grew more and more impatient with Rati’s love for anything Indian and finally burst out in frustration when he saw her zealotry showed no signs of subsiding. Boarding a local train a few moments before the departure time, Rati made a motion to sit next to an Indian male passenger before Paul intercepted and took the last empty seat himself. Rati was left to stand, but she caught Paul’s look of self-satisfied smugness at having successfully kept Rati from making another Indian acquaintance, a man who might serve as a further threat to their relationship.§

Later, when Rati confronted Paul about his sneakiness as well as his lack of confidence in their relationship, Paul admitted that after dating her he “could never date another Asian again” for fear that he would not be taken seriously since he was not Asian. When pressed further, Paul accused Rati of preferring Indians to whites and of “being a racist.” Rati’s anecdote about dating Paul, a white man, is interesting because it highlights the second generation’s enthusiasm for and the significance they place on “being Indian” and relying on activities like practicing yoga to express Indianness. Watching Bollywood movies, eating vegetarian, practicing yoga, learning Indian classical dance and other activities are significant in describing the second generation’s understanding of India, their own ethnic-American identity and the characteristics they seek in a marriage partner. After the incident described above, Rati dumped Paul and relinquished the American notion of falling in love and pursuing a “love marriage.” Shortly thereafter, she posted an online matrimonial ad in shaadi.com. Therein began her adventures and misadventures that would eventually lead her to meet and marry her Indian-American husband, Shiv.§

4. The Girl’s Qualities

PPEARANCE, PERSONAL CHARACTER AND HOMEMAKING ABILITY are generally foremost in the consideration of the girl. She should be shorter than the boy, have a pleasant walk, a feminine voice, modesty and good health. Her potential as a future wife is judged by observing her mother, grandmother and sisters. And, like the boy, inquiry regarding her character and temperament is made among her relatives, friends, teachers and fellow students. Her religious inclinations (even more so than the boy’s) and education are important. Some skill in music or dance is a plus, but extensive stage performance or involvement in sports is traditionally frowned upon. Since having children is a primary purpose of Hindu married life, the desirable girl comes from a large family—an indication that she herself will have many children. A girl from a small family—especially an only child, or one without a brother, is at a disadvantage. In recent decades the girl’s ability to hold a job and earn money have became a paramount consideration for some, even above religious, cultural and child-rearing considerations. The trend may be related to the demands for dowry in which the boy’s family approaches the marriage with financial gain in mind, as well as to pressing economic conditions.§

PPEARANCE, PERSONAL CHARACTER AND HOMEMAKING ABILITY are generally foremost in the consideration of the girl. She should be shorter than the boy, have a pleasant walk, a feminine voice, modesty and good health. Her potential as a future wife is judged by observing her mother, grandmother and sisters. And, like the boy, inquiry regarding her character and temperament is made among her relatives, friends, teachers and fellow students. Her religious inclinations (even more so than the boy’s) and education are important. Some skill in music or dance is a plus, but extensive stage performance or involvement in sports is traditionally frowned upon. Since having children is a primary purpose of Hindu married life, the desirable girl comes from a large family—an indication that she herself will have many children. A girl from a small family—especially an only child, or one without a brother, is at a disadvantage. In recent decades the girl’s ability to hold a job and earn money have became a paramount consideration for some, even above religious, cultural and child-rearing considerations. The trend may be related to the demands for dowry in which the boy’s family approaches the marriage with financial gain in mind, as well as to pressing economic conditions.§

RAJEEV N.T.§

Music and dance, art and handicraft are indicative of a girl’s training and skills, molding, rearranging and working with herself, abilities she will use as she moves in with a new family and makes it her very own.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •§

Arranged Meetings: a Third Paradigm

For second-generation Indian-American Hindus, there are two models for marriage: the arranged marriage and the love marriage. These models are diametrically opposed. The love marriage usually involves a whimsical and incidental meeting followed by months and often years of dating. The arranged marriage excludes dating altogether and in fact rarely allows for more than one meeting before the wedding day.§

So, how do second-generation Indian-American Hindus negotiate these two opposed models of marriage? How do they reconcile love marriage with arranged marriage? “Arranged meetings” is an already negotiated and well-established third model for marrying among second-generation Indian-American Hindus. The second generation uses this method to filter out prospective marital candidates who do not have the “right” ethnic, religious, linguistic and regional traits desired by their parents. For example, a family active in the Gujurati Hindu community can seek only fellow Gujurati Hindus to introduce to the eligible son or daughter. Any marital candidate left standing is fair game for something akin to dating. The second generation feels free to determine whether the meaningful candidates have sexual chemistry and compatible personalities, characteristically American criteria contemplated in making a “love marriage” decision.§

In this way, neither arranged nor love marriage are excluded, and the needs and desires of both generations are respected. The first generation is still involved in finding a suitable partner for their child, whether through introductions by family and friends, or placing an ad online or in a newspaper. Additionally, candidates who do not come from the same religious sect, speak the desired dialect, or originate from the same region of India (and thus possibly eat dissimilar food), are cast away before a set of eligible prospects are considered. Then second-generation Americans embark in all the activities associated with pursuing an American “love marriage.” They date for months and sometimes even years, determining whether she and her partner share common likes and dislikes. They also determine, and not just by holding hands, whether there is enough sexual attraction to keep their mutual attentions “’til death do we part.”§

Along with their immigrant parents, most of the second-generation Indian-American Hindus I met prefer to marry a partner of Indian heritage and Hindu faith because marriage is seen as a definitive way for the second generation to express its identity as ethnic and religious Americans. They are American, yes. But they are also Indian and Hindu. Additionally, pleasing the first generation’s wish to see their children marry a Hindu Indian is itself an expression of ethnicity, of one’s Indianness, in this case with respect for the traditional value of deference to one’s elders.§

5. Verifying Compatibility

DEALLY THE COMPLETE CHARTS OF THE BOY AND GIRL will be calculated and analyzed by a competent astrologer. There is also a simplified system of ten tests based on a comparison of the boy’s and girl’s nakshatras (birth stars) and rasis (moon signs) used in the absence of a complete comparison to diagnose the physical, mental and emotional compatibility of the couple, plus future health, number of children, financial success and longevity. Customarily the astrology is examined early on in the evaluation of a match. The preliminary tests of rajju, vedhai and what is known as “Mars affliction” identify a few (about 20%) very inauspicious combinations which predict great misfortune in marriage, or divorce. The second eight tests are allotted one to eight points each, for a total of 36. A happy and lasting marriage usually requires a score of more than 18 points. For example, the test of nadi, given 8 points, predicts emotional intimacy or lack thereof; that of yoni, given 4 points, indicates physical compatibility, marital harmony, faithfulness and children. Astrology is a good but not perfect predictor of marital success. The great Hindu astrologer Rishi Kalidasa advised, “Even if by these matchings the girl gets more than 20 marks, if the boy does not really love the girl, a marriage will be futile.” §

DEALLY THE COMPLETE CHARTS OF THE BOY AND GIRL will be calculated and analyzed by a competent astrologer. There is also a simplified system of ten tests based on a comparison of the boy’s and girl’s nakshatras (birth stars) and rasis (moon signs) used in the absence of a complete comparison to diagnose the physical, mental and emotional compatibility of the couple, plus future health, number of children, financial success and longevity. Customarily the astrology is examined early on in the evaluation of a match. The preliminary tests of rajju, vedhai and what is known as “Mars affliction” identify a few (about 20%) very inauspicious combinations which predict great misfortune in marriage, or divorce. The second eight tests are allotted one to eight points each, for a total of 36. A happy and lasting marriage usually requires a score of more than 18 points. For example, the test of nadi, given 8 points, predicts emotional intimacy or lack thereof; that of yoni, given 4 points, indicates physical compatibility, marital harmony, faithfulness and children. Astrology is a good but not perfect predictor of marital success. The great Hindu astrologer Rishi Kalidasa advised, “Even if by these matchings the girl gets more than 20 marks, if the boy does not really love the girl, a marriage will be futile.” §

RAJEEV N.T.§

Astrologers match and calculate based on ten points. Modern couples may choose to use websites that offer the same service, some for free! Having a skilled, experienced and patient astrologer is key.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •§

Ethnic Capital

This idea provides additional ammunition against the “melting pot” metaphor. Within the second-generation Indian-American Hindu ethnic minority, men and women of marriageable age who have high economic and social standing prefer to marry within their community rather than engage in an exogenous marriage. Rather than participate in a “melting pot” as early ethnic scholars described the trajectory of ethnic Americans, participants chose to marry people from within their community despite the New York area’s diverse population.§

Rather than debating values and characteristics second-generation Indian-American Hindus should seek in a partner, the first and second generations have already negotiated a compromise whereby the second generation engages in various methods for meeting a partner that meet all or most of the immigrant generation’s religious, ethnic, regional, and linguistic cultural criteria. At the same time, the prospects who make it through this sieve of criteria are then free to engage in dating relationships that look typically American. For instance, Shiv and Rati were attracted to each other’s profiles because they shared the same regional and religious Indian identity; however, they dated for two years before marrying. Their mutual love for Indian performance was what bonded them together in terms of sharing common interests.§

The Indian-Hindu community has evolved enough in the last forty years that mechanisms are already in place for the second generation to search for potential marriage partners. These mechanisms respect both traditional Indian as well as modern American criteria. “Arranged meetings” provide a group of candidates acceptable for a member of the second generation to fall in love with after having satisfied the first generation’s ethnic and religious requirements.§

Second-generation Indian-American Hindus seek marriage partners who have what I describe as “symbolic ethnic capital.” This finding sheds light on how the second generation envisions and understands Hindu India. The men and women in my study scrutinize characteristics in the opposite sex in order to confirm if that marital prospect is “Indian” enough for marriage. Like Rati obsessed over getting better-acquainted with her Indian heritage through practicing yoga, learning Indian classical dance, and watching Bollywood movies, other participants used similar activities as markers for Indian ethnicity among marriage prospects. Being ethnically Indian and from a Hindu family was often not enough. Especially “expressive” Indian-American Hindus desired a marriage partner who could further confirm their identity as Indian-American Hindus.§

6. Introducing the Couple

HE COUPLE MEETS ONLY WHEN THERE IS A FAVORABLE outcome to the investigation of each family, the astrological compatibility, the characteristics of the boy and girl and the preliminary meetings of the parents. In previous times, and still in some areas, the girl would be secretly pointed out to the boy and his family at a public event such as a temple puja. Today a preliminary exchange of photographs largely replaces this custom, which prevented a girl from being faced with a number of outright rejections. Usually the boy and his family will go to the girl’s home for their first meeting. The parents will sit and talk, and the girl—who may be aware but is not told of the purpose—will be asked to come in and serve tea to the “guests.” How she reacts to requests, her dress, appearance, speech, behavior toward her parents, brothers and sister and rapport with young children are all noted by the boy and his family. After she leaves the room, the boy states if he has a favorable impression. If so, the girl is asked privately about the boy. If both are agreeable, they talk privately together, perhaps walking in the garden for an hour with young children as escorts. Sometimes more meetings are held. A final decision is then made requiring agreement of six people—the four parents, the boy and the girl.§

HE COUPLE MEETS ONLY WHEN THERE IS A FAVORABLE outcome to the investigation of each family, the astrological compatibility, the characteristics of the boy and girl and the preliminary meetings of the parents. In previous times, and still in some areas, the girl would be secretly pointed out to the boy and his family at a public event such as a temple puja. Today a preliminary exchange of photographs largely replaces this custom, which prevented a girl from being faced with a number of outright rejections. Usually the boy and his family will go to the girl’s home for their first meeting. The parents will sit and talk, and the girl—who may be aware but is not told of the purpose—will be asked to come in and serve tea to the “guests.” How she reacts to requests, her dress, appearance, speech, behavior toward her parents, brothers and sister and rapport with young children are all noted by the boy and his family. After she leaves the room, the boy states if he has a favorable impression. If so, the girl is asked privately about the boy. If both are agreeable, they talk privately together, perhaps walking in the garden for an hour with young children as escorts. Sometimes more meetings are held. A final decision is then made requiring agreement of six people—the four parents, the boy and the girl.§

RAJEEV N.T.§

A potential match? Content with all requirements, the parents arrange a venue for the boy and girl to meet and talk.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •§

A number of factors are important in the Indian-Hindu American community when it comes to finding a mate in a limited and dispersed pool of partners. Processes such as placing matrimonial ads in ethnic newspapers and online allow second-generation Indian-American Hindus to meet fellow Americans as well as Indian Hindus in England, Canada, India and Singapore. These mechanisms are important because they allow second-generation Indian-American Hindus to meet partners that satisfy the first generation’s religious and ethnic criteria as well as the community’s desire to find a partner with symbolic ethnic Indian and America capital.§

Finding a potential partner through newspaper and on-line matrimonial ads was followed by typically American patterns of dating which included a long courtship designed to ferret out similar hobbies and the quality of sexual chemistry. By meeting a potential spouse through a family network or other family sanctioned modes of pursuing marriage, such as online matrimonials, second-generation Indian-American Hindus accrued symbolic ethnic Indian capital they later spent when in long-term relationships and premarital sex. Mainstream American dating was encouraged by my participants’ immigrant parents to ensure that romance and love, two values that express Americanness, were as much a part of their children’s decision to marry as religious compatibility and regional identity.§

Rati and Shiv Meet through Shaadi.com

Rati, whose mother is a white Lutheran woman from Canada and whose father is a Hindu raised in Uttra Pradesh, India, literally chose to “be Indian.” The story of how Rati decided to utilize shaadi.com—an on-line Internet matrimonial website popular among South-Asian Hindus—supports my notion that, for second-generation Indian-American Hindus interested in expressing their ethnic-American identity, marrying a fellow Indian-ethnic Hindu is the most effective way. Coming from a bi-cultural family, Rati was not exposed to Indian-Hindu culture until her twenties, when she made conscious efforts to adopt Indian-Hindu religion and customs. Rati is both a career-minded professional dancer and an Indian-American woman seeking to establish a family to uphold the Indian and American sides of her identity. Rati reports that her parents’ attitude was: “When you want [religion] in your life, you’ll go find what works for you.”§

As if applying for a job, Shiv, Rati’s future husband, sent a competitive biodata, or resume, to Rati in response to her picture and profile on shaadi.com. After first talking on the phone for three and a half hours, Rati and Shiv began having regular phone conversations before she visited him in New York. After her first visit, they began seeing each other every other weekend for three months before getting engaged.§

7. The Betrothal Ceremony

HE BETROTHAL IS CALLED VAGDANA, “word giving,” a practice described in the Vedas. The boy’s family is invited to the girl’s house where the girl’s father formally promises that his daughter will marry the boy. This promise is binding and very unlikely to be broken before the wedding. The oral promise is essential and standard throughout India, though specific betrothal customs vary considerably. Most, if not all, communities practice exchange of visits and gifts between the families as part of sealing the agreement. The gifts from the groom’s family include clothing and cosmetics for the girl, while her family give clothing for the boy.§

HE BETROTHAL IS CALLED VAGDANA, “word giving,” a practice described in the Vedas. The boy’s family is invited to the girl’s house where the girl’s father formally promises that his daughter will marry the boy. This promise is binding and very unlikely to be broken before the wedding. The oral promise is essential and standard throughout India, though specific betrothal customs vary considerably. Most, if not all, communities practice exchange of visits and gifts between the families as part of sealing the agreement. The gifts from the groom’s family include clothing and cosmetics for the girl, while her family give clothing for the boy.§

Other home observances include applying tilak to the boy, the giving of a gold necklace to the girl by the boy’s mother—often the necklace she received at her own betrothal—and/or the more modern exchange of rings. In some areas the womenfolk sing humorous songs. A formal religious ceremony (kanyavarana) may be conducted by priests, but often the whole matter is handled in an informal manner. In Sri Lanka, for example, frequently a civil wedding is held immediately upon the decision to marry, with the formal religious marriage taking place later. Commonly it is just a matter of weeks between the betrothal and the marriage, which is held at an astrologically auspicious day and time.§

RAJEEV N.T.§

The betrothal is a mini-marriage. With most of the family and friends in attendance, rings are exchanged and the wedding date is set. A grand feast follows.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •§

Rati describes meeting Shiv on the matrimonial website as making their relationship more honest and open than if they had they met in a bar or through a friend. She tells me how “all the questions you want to ask on the first date” about marriage, family, education, and salaries “you can’t ask” when meeting through conventional methods but that by the time six months roll by and “you’ve figured out what a guy is all about, that’s six months of your life wasted.” As she puts it, “On shaadi.com no one is there for a booty call. No one wants to date for fun or pass time.” Plus, all the uncomfortable questions regarding money and salaries are already answered in the bio-data, leaving the boy and girl more time and energy to focus on discovering whether the two have chemistry and are compatible for marriage. Rati and Shiv’s families were from the same region in India and belonged to the same caste, two criteria that led Shiv to Rati’s advertisement through the click of a few scroll-down menus. Having pre-determined that they were compatible in terms of region and caste, the two were free to pursue an American-style romance. But, as Rati describes it, “The elders could not have done a better job putting the two of us together.” Rati engaged in two models of marriage, the arranged one as well as the love one, in her arranged meeting. Rather than reject either the traditional Indian or modern American models for marriage, she embraced elements from both traditions in choosing a spouse. It took her parents’ divorce and her trip to India to move Rati to express her Indianness and thereby her Americanness. Rati claimed her Indian heritage upon returning from India and married Shiv to reinforce her ethnic-American identity.§

DREAMSTIME§

Whether their meeting is arranged or by choice, a couple needs time to spend time together to understand each other well. While traditionally such meetings are chaperoned by an elder, and touching is taboo, a couple deciding on their own are more liberal.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •§

Hamsa and Nalin

Whereas Shiv and Rati’s courtship began with Shiv’s response to Rati’s online matrimonial advertisement, Hamsa and Nalin met through friends while students at the University of Wisconsin. Nonetheless, Hamsa and Nalin’s story (like Shiv and Rati’s) emphasizes the significance among second-generation Indian-American Hindus of finding not only a co-ethnic marriage partner but also a spouse who carries a certain level of knowledge of Indian culture and Hinduism.§

8. What About Dowry?

HERE IS NO HINDU SCRIPTURAL OR LEGAL BASIS for the payment of dowry—that is, giving money to the boy’s family to secure a marriage. It was unknown in early India and arose only in recent times. In the last few decades abuse has reached such proportions that newly married girls are even murdered in disputes over dowry! Marriage arranging has become for some a process of extortion from the girl’s family.§

HERE IS NO HINDU SCRIPTURAL OR LEGAL BASIS for the payment of dowry—that is, giving money to the boy’s family to secure a marriage. It was unknown in early India and arose only in recent times. In the last few decades abuse has reached such proportions that newly married girls are even murdered in disputes over dowry! Marriage arranging has become for some a process of extortion from the girl’s family.§

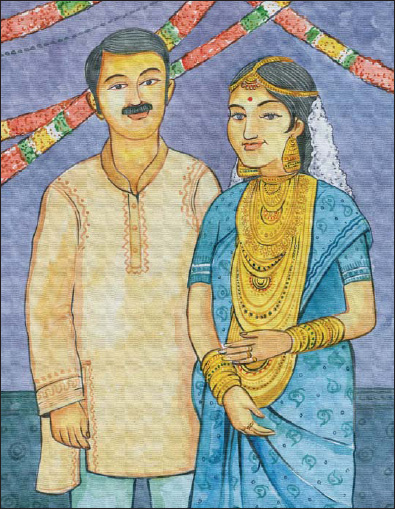

The proper Hindu custom is stridhana, “women’s wealth,” by which an abundance of jewelry and gold is given to the girl at the time of her marriage. This is her personal wealth, intended to provide security in case her husband dies or abandons her, especially after her own father’s death. Legally, it remains her personal property during the marriage and must be returned upon a divorce. A wealthy Hindu bride might possess a pound or more of gold. Also, she would bring to her new home everything needed for housekeeping. A related money issue is the expense of wedding festivities, which in India can run up to several years’ salary of the bride’s father. Lavish weddings are a worldwide custom, cutting across all religions and cultures, but reason should prevail in deciding how much to spend.§

RAJEEV N.T.§

Jewelry and other gifts are exchanged and exhibited in an attempt to assure each other of their sound financial and social standing.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •§

In one photograph, Hamsa sits with her chin in one palm while Nalin stands behind her hugging his hands around her neck. In another the two playfully hold hands and stand across from one another as if they are about to whirl in circles. Rather than look demure, as Indian tradition would dictate, Hamsa smiles like a love struck Bollywood actress and Nalin looks like a young Amitabh Bachan (one of Bollywood’s most famous actors).§

Hamsa is embarrassed when I comment on how much I enjoy looking at her wedding portraits. “Yes, well we did whatever our Indian wedding photographer told us,” she says. “Those poses aren’t natural to us, but they’re typical Indian wedding poses.” What intrigues me in my conversations with Hamsa and Nalin is their inability to distinguish modernized India from the India they have configured for themselves in their imaginations. To them, India is one homogenous country with one homogenous tradition. This confession is even more striking for me because Hamsa and Nalin are a regionally mixed couple. Nalin’s family is from Gujarat in Western India, and Hamsa from Andhra Pradesh in South India, yet they consistently ignore the diversity of cultures within the country and remain ignorant that their own “traditional South Indian” wedding was a hybrid one.§

Ironically, Hamsa and Nalin’s “pure Indian-Hindu” wedding reveals how there is no pure “India.” As the couple’s wedding attests, India is made up of many different regional cultures and a myriad of religious faiths and languages.§

Nalin was not the first Gujarati North Indian man Hamsa dated either. She tells me that although she had many friends in her ethnically diverse high school, she did not date until she arrived at college. “I had one two-month long relationship with a Gujarati Indian guy before I met Nalin,” she tells me. But apparently he wasn’t Indian enough: “He was very different from Nalin. My ex-boyfriend wasn’t very knowledgeable of his background, and he didn’t have an Indian community growing up in West Virginia; he wasn’t familiar with the religion and didn’t know the language. He’d never been to India. That’s why I didn’t connect with that guy. He was very apathetic about being Indian.”§

Knowing about India was something Hamsa actively looked for in a partner. Like Nalin, she wanted to find a partner she could love but who could also assert his “Indianness,” thereby reinforcing her own symbolic ethnic Indian capital, and in the process her own Americanness. She wanted to marry a man knowledgeable of his Indian-Hindu background to reflect her own cultural and religious ties with India. While outsiders might posit that Hamsa’s wish to exclusively date Indians depletes her American symbolic ethnic capital, I argue that it instead makes her more American.§

Nalin reports he was very intentional about exclusively dating and marrying Indian women:§

“From the very beginning I always knew I would meet all types of people, but in terms of marriage I wanted to marry someone with the same cultural values. It would be easier and we would get along better. Around high school I made that choice when I started seriously thinking about dating and figuring out what I was looking for.”§

When asked what values are specific to Indian Hindus, he recognizes that values are found across cultures and re-formulates his thoughts. “It was more cultural, going to temple. Growing up, I think Indian culture brought about family closeness; family came first. In college I never thought about dating a non-Indian.” When asked whether his parents were upset that he married a non-Gujarati girl, he responds, “In a perfect world I would have married a Gujarati girl, but they are educated enough to know that compatibility is more important.”§

Indian Hindu youth may today balk at having their marriage arranged by their parents, but they do understand the need for “due diligence” in selecting a life-long partner and are not falling into the dubious Western pattern of marrying out of “love at first sight”

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •§

During their two-year courtship at the University of Wisconsin, Hamsa and Nalin moved to San Diego for a summer where they interned and took classes. In San Diego, they tell me, they fell in love. “I didn’t think I couldn’t live without him,” Hamsa tells me, “but I thought I would be sad if he ever left.” Hamsa presses her two index fingers into her fluffy comforter and they travel, making an upside down V, until they meet at the same point. “That’s how we were; we started off in different places and spent enough time together dating that we pulled each other in the same direction,” she explains. For her, love for her husband was not love at first sight, but still conformed in a way to the traditional Indian view of love where one marries first and later grows to love one’s spouse. For Hamsa, a couple dates and then grows to love one another.§