CHAPTER 10: WILLPOWER§

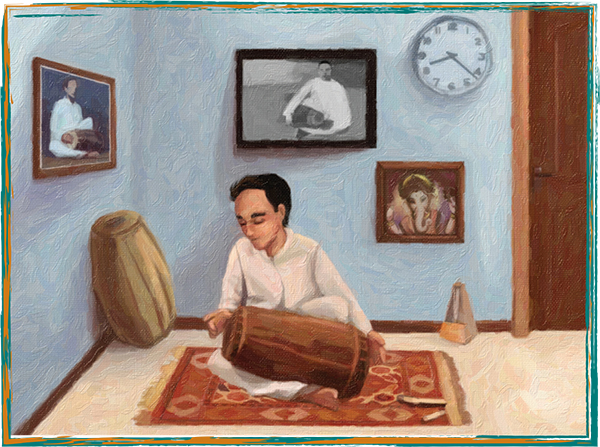

My Son, Drummer Divine§

Mridangam prodigy Ravi Padmanabhan was recently in town and performed with a singer and a tambura player before three standing-room-only crowds at the Wellesley Theatre. After hearing a brilliant performance, our (fictional) London reporter sat down with Nageswaram Padmanabhan, the artist’s father, to hear the story of his son’s long, hard road to acclaim. §

Reporter: How old was Ravi when you first noticed his talent?§

Nageswaram: He was a baby. Whenever his mother sang bhajans or we had music in the background, he seemed to have a sense of rhythm about him expressed in his body movements. At an early age, we would see him finger drumming on things, making up his own beats. At the time it was more of a curiosity; it wasn’t like we told ourselves, “Our son’s going to be a famous drummer!” But we bought him a little statue of Ganesha playing the mridangam, and he kept it beside his bed. Then I remember one day—I think he was three—we were at a temple festival listening to an excellent thavil player. My older children were disturbed by the volume and the piercing sound of the nadaswaram. But Ravi wasn’t. He started to dance with the music, while keenly watching the drummer’s hands. The thavil player noticed him and motioned him over during a break. He taught Ravi a few simple rhythms and then did an improvised duet with him for a minute. “The child has talent,” the drummer told me. After that, we took him to concerts whenever the opportunity arose. §

Reporter: Is what he is today the result of natural talent alone?§

Nageswaram: (laughs) Oh no. Not at all. He had lots of talent, but no focus. He would drum with his fingers for five minutes here and there, or do voiced carnatic rhythms in the car, then run off to play with his friends. His energy was all over the place. His teachers at school commonly wrote, “Ravi is a capable student but lacks focus. He needs to direct his energies.”§

Reporter: Obviously all that has changed now. Watching him perform, I see he has incredible focus. He seems totally alone in a world of his own where only music exists. What brought about the change?§

Nageswaram: You might think we bought him a drum, but actually we didn’t. I figured he would wreck it. He had so much wild energy! His mother and I first did some research within spiritual literature and psychology to help us figure out how to help him. §

Reporter: So you conditioned him, trained him?§

Nageswaram: (laughs) Yes, we trained him. Better put, we helped him train himself. Not in music at first—in life skills. We learned and taught him about willpower—the more you use it, the more you have to use. Other skills as well. All the books say to start slow, work your way up. Then there was the key idea of interest, or passion—that anything in life is easier if you have a natural interest in it. Athletes love sports, musicians love music, scientists love science. Another life skill we focused on was cleanliness. §

Reporter: How did that relate to the music? §

Nageswaram: We used one to help with the other. When he was little, he had difficulty with taking baths, brushing his teeth, cleaning up after himself—too busy to remember, or better things to do. So we made a game of it. We had him brush his teeth to his own beats and rhythms. He had incredibly clean teeth for awhile. We gave him a goal of continuous brushing for one whole minute, then two. Before that he would make two swipes, and say he was done. Being urged to create music while brushing helped him be more thorough and consciously conscious. §

Reporter: Then what?§

Nageswaram: That convinced him he could stay on task for two minutes straight, which back then was a long time. Then we shifted to cleaning his room, then to helping his mother by cutting vegetables. The emphasis was not only on doing the task, but completing it and doing it well. He learned that unfinished tasks can build up, and a long list of things still undone makes anyone feel burdened and ill at ease. The cycle of unfinished tasks and procrastination becomes a habit. To avoid that pitfall and remain in the now, Ravi learned the value of finishing each thing he starts, and doing it to the best of his ability. §

Reporter: Sounds too easy. Surely there must have been failures. §

Nageswaram: Lots of them. But we persisted. Starting with small increments of time was an important tactic. One of his tasks was to water the garden regularly. To provide sufficient water to all the plants takes about half an hour. At first he came in after a few minutes claiming it was all done. Going out to check, I found that several patches were still parched. He admitted to skipping them, complaining how boring it was. So we divided the landscape into three parts, watering each section for ten minutes at different times. That was far more manageable. §

Reporter: How was he at school over the years?§

Nageswaram: Quite similar. His school success progressed gradually. We had to allow for short shifts in homework. He was unable to sit for an hour straight. But ten minutes on, ten minutes off, for two hours amounted to the same thing. It was actually even more productive, because knowing he would get a break in ten minutes, he focused more intensely on the work. His productivity went up. This phenomenon is well researched and documented now. Few young people are capable of concentrating for long stretches. Business owners are realizing the old Henry Ford assembly-line model actually decreases productivity over a period of time. The workers just get bored and slow down. §

Reporter: Was there ever a key turning point, an “aha” moment?§

Nageswaram: At age twelve he went to his mother and announced, “Mom, I want to be a professional drummer!” It was a surprise to us; we hadn’t yet started him on lessons. Our first response was, “But, Ravi, you would to have to work so hard.” I wasn’t sure he could manage it. I had read biographies of Indian musicians and knew a few personally. They assured me image of the “starving artist” trying to make it professionally was no joke. I knew how much practice time they put in. I told him it was a difficult life, and that success was more uncertain than in other careers. But he was not dissuaded.§

Reporter: What did you do then?§

Nageswaram: We took him for an interview with his first teacher, Mr. Shankaran, here in London, to see if Ravi had the qualities needed to receive instruction. In Indian culture, you can’t just pay a lot of money and hire a teacher regardless of your potential. The traditional way is to prove your worth and be accepted by the teacher.§

Reporter: That sounds like an interesting encounter.§

Nageswaram: It was. I thought it would be all about music. We admitted to the maestro that Ravi had not taken lessons, but seemed to have innate talent. Shankaran clapped out a few rhythms and asked Ravi to repeat them. Some were fairly complex. We were surprised how closely Ravi was able to replicate them. As the exercises proceeded, we noticed for the first time the fluid looseness of his movements, a quality we enjoyed in good drummers. Shankaran asked Ravi about willpower, not just how to use it, but what it is. Our son answered, “It’s unlike other forms of energy, which diminish as they are used. The more willpower you use, the more you have to draw from.” The teacher was testing whether Ravi had the mental strength to make it. §

Reporter: I take it he was accepted for training?§

Nageswaram: Only conditionally at first. When the teacher was asking about finishing tasks, Ravi looked at his mother and me, begging us not to elaborate. I was thinking at the time, “My, you’ve got the wrong man. This chap can’t finish anything!” But I stayed silent, and because Ravi was so eager to try, Shankaran took him on. I figured Ravi would last a month or so, but happily he proved me wrong. §

Reporter: How was that first month?§

Nageswaram: We knew that we had to help him gain more self-discipline if were to make this venture a success. We redoubled our efforts to have Ravi finish what he started. Motivated by the opportunity to learn drumming, which he clearly loved, he was eager to cooperate. If we asked him to clean his room, he would do it completely. He wouldn’t start the next task unless this was done. This discipline helped him to keep his awareness concentrated. §

Reporter: Tell me about the music. §

Nageswram: The mridangam practice was done right on schedule, the same amount of time each day. The same principles applied in practice: take up one task, or rhythm, and practice it to perfection, then the next. No skipping on, or back, to easier parts. It wasn’t a matter of just putting in the time, we told Ravi again and again, you must apply your willpower. Reading more about the subject, I learned that if a short-term goal isn’t sufficiently motivating, you need to become engaged in a bigger picture. When Ravi found the practice monotonous, I reminded him of his love of music and his goal of becoming a world-class drummer. §

Reporter: This couldn’t have been easy for a twelve-year-old.§

Nageswaram: Sure, there were days when he struggled. That’s normal. The regimen was to practice five days of seven each week. He learned to organize and execute the various tasks of his life and school, and he learned how to time-manage his practice sessions. Once he got into that rhythm, so to speak, his progress was surprisingly rapid.§

Reporter: Did he get holidays, total breaks from it?§

Nageswaram: Yes. Those helped, too. We went on vacation to India, leaving the mridangam at home. I think it came along in his head though. The flight attendants on the Air India flight noticed his fingers working away. One even came and asked him to play, like air mridangam. We all had a good laugh. It broke the boredom of the plane ride. §

Reporter: Was there ever a point when he wanted to give up?§

Nageswaram: Never. At least not that he ever let on to me. §

Reporter: In Ravi’s bio I read that he studied in India. How did that come about? §

Nageswaram: Mr. Shankaran’s teacher, Skandanathan, came here to give a concert. Shankaran took all his students to see the amazing performance, and brought them backstage afterwards. Ravi, then fourteen, was floating on a cloud of bliss. Each student had been asked to prepare one question for the Indian master. §

Reporter: What was Ravi’s question?§

Nageswaram: “Where does the music come from?”§

Reporter: Nice question! What was the answer?§

Nageswaram: “The Gods.” He told Ravi there is an entire category of divine beings called gandharvas, celestial souls who do nothing but make music all the time. To make divine music, one has to learn to hear the gandharvas playing in the Devaloka and play along with them here on Earth. Looking Ravi straight in the eye, Skandanathan proclaimed, “When you can make music like they do, then Siva Himself will dance for you.” Some of the other students rolled their eyes, gesturing “Yeah, right.” But not Ravi. He ventured a second question, “How can I learn to do that?” “Once you have mastered your instrument, it takes devotion and meditation,” came the answer, “Devotion and meditation.” After that meeting, our visits to the temple took on new meaning, plus Ravi hauled me off to meditation class. Our roles reversed. It was he pressuring me. In the meditation classes, we learned to feel the energy in our spine, and the energy in our head, which is the source of the energy in our mind and emotions. Ravi caught the idea that music comes from tapping into this energy and letting the divine inspiration flow out in notes and rhythms.§

Reporter: He could actually do that?§

Nageswaram: Yes, I was amazed. As he became more devotional, poised and introspective, his music changed. That divine quality you heard tonight started to appear. Sometimes I would look at him practicing and almost see the gandharvas floating above him, furiously playing in a celestial concert with their human colleague. §

Reporter: How many hours a day did he practice?§

Nageswaram: You may be surprised, but for the first six years he practiced just ninety minutes a day, in three sessions of thirty minutes each. You should have seen him, so concentrated, so determined to get the rhythms right, so keen to teach his fingers to do what his heart could hear. I think he progressed more in one of those half-hour sessions than most students do in two hours. Plus, by breaking it up, he was fresh for each round. We also set out five opportunities per a day for three thirty-minute session. If he missed one, he could use an alternative time slot. That way he rarely failed to meet his ninety-minute goal. §

Reporter: But he didn’t go to study in India right away, did he?§

Nageswaram: No. We wanted him to finish high school, but more importantly, he wasn’t ready musically. He had more work to do with Shankaran. He had to get near the level his teacher had attained, to study with Shankaran until he could take him no farther. He also had to mature as a person. He had to realize that the most beautiful music is the most disciplined music. And because his practice sessions were not too long, he still had time for other things important to a teenager. In India the demands would be far more...well, demanding.§

Reporter: Who finally decided that he go to India for those years of advanced training?§

Nageswaram: God. To become the remarkable drummer Ravi is today, it took God’s grace, which he received through the temples, through his meditation and his communion with the devas of music while playing. To those blessings add his innate talent, a passion for the art, diligence, willpower and practice and you have an inkling of how his prodigious musical gifts evolved. When his mother and I hear him play, and then watch the audience respond, all those years of work, work, work seem mercifully distant. Like the audience tonight, we get to bask in the joy and transcendent spirit of a divine music our son is bringing to the Earth. §