Village Mysticism

ach Hindu community on the Indian subcontinent has its own Gramadevata, literally “village Divinity,” the Deity regarded as synonymous with the locality and everything within it. Just as the home is viewed as a composite of the spirits of all of its inhabitants and of the materials that went into its construction, so also is the community a blend of its physical, spiritual and emotional components. Every house, every street, all of the shops, the craft studios, the barns, the farms, the trees and bushes, the wells, the reservoirs and streams, the inhabitants (people, animals and insects), the spirits of those who have lived and died there, and even the activities, thoughts and emotions of everyone living there―all are part of one great spirit identified as a Deity, a Gramadevata. This Deity is the community, just as the community is the Deity. They are inseparable.§

ach Hindu community on the Indian subcontinent has its own Gramadevata, literally “village Divinity,” the Deity regarded as synonymous with the locality and everything within it. Just as the home is viewed as a composite of the spirits of all of its inhabitants and of the materials that went into its construction, so also is the community a blend of its physical, spiritual and emotional components. Every house, every street, all of the shops, the craft studios, the barns, the farms, the trees and bushes, the wells, the reservoirs and streams, the inhabitants (people, animals and insects), the spirits of those who have lived and died there, and even the activities, thoughts and emotions of everyone living there―all are part of one great spirit identified as a Deity, a Gramadevata. This Deity is the community, just as the community is the Deity. They are inseparable.§

Towns and cities have many individual subsections, each of which usually has its own Gramadevata. For example, every small locality in the Rajasthan city of Jodhpur has a God or Goddess that has been worshiped in that spot for as long as the community has existed. While most cities are internally divided into numerous smaller entities, a municipality may also be viewed as one great Deity, interwoven with all the inclusive Gramadevatas.§

In this way, the entire southern Indian city of Madurai is believed to be the Goddess Meenakshi, the Gramadevata of the initial community that lived there. Her power is believed to be so immense that several kingdoms during the past millennia have owed their greatness to Her beneficence. Many thousands of pilgrims from all over India visit Her temple for Her darshan every year.§

Most Gramadevatas are feminine―associated with the Earth, fertility, healing and protection. Their names often reflect their association with the Mother Goddess: they are usually prefixed or suffixed with Ma, Mata, Matrika or Amman (each a regional translation of “mother”), Ben or Bai (sister) or Rani (queen). Sometimes their regional identities have been merged with that of a greater pan-Indian Deity, such as Durga or Mari.§

For example, the Gramadevata of many southern Indian communities is Mariamman, while seven temples to the Goddess Durga Ma surround and guard the royal city of Udaipur. According to Hindu numerology, seven is particularly auspicious. Seven Mothers (Saptamatrika) are believed to guard many towns throughout the subcontinent, each Mother a specific aspect of the great Divine who may be beseeched in times of particular need. Together They are inseparable from the community that They incorporate. Their images may be delicately carved to delineate the various attributes of the individual Goddesses, but most often They are represented simply by a row of seven sacred stones placed beneath an ancient tree.§

Shrines

Although Gramadevatas are indivisible from Their communities, each must have a focal point, a specific place or object on which to direct attention. The devasthana, or shrine, of a Gramadevata is usually associated with an important natural feature: a hill, a boulder, a stream or pond, a tree or grove of trees. Trees are by far the most common: there are hundreds of thousands of sacred trees being worshiped constantly in India. Most are ancient, venerated as Gramadevatas for untold centuries in the same way that the pipal tree (Ficus religiosa, a kind of banyan) is worshiped by Lalubhai and his family in the story on page 56.§

Nagpur, Puri District, Orissa: A farmer prostrates himself in prayer beneath a sacred pipal tree that his village worships as the Goddess-Spirit of their community.§

The appearance of these tree sanctuaries is as varied as the communities themselves: sometimes there are several trees together, or a single tree with a large platform built around it, or one marked with flags and banners, or one with its trunk dressed like the Goddess Herself. The devasthana may be in the center of the village or in the fields beyond the farthest house. When the tree dies, the spot remains sacred. It is believed to be vibrant with the energies of innumerable pujas and will usually continue to be a focus of community worship, most often with a platform or building constructed where the tree stood.§

The shrines in brahmana villages or those with brahmana occupants are usually overseen by brahmana priests. Pujas that take place in devasthanas in those many communities without brahmana occupants are often facilitated by non-brahmana priests, often because the community simply may not be able to afford to hire a brahmana. Conversely, a single brahmana in a village might feel isolated and therefore not want to move there.§

The position of priest may be hereditary, usually given to a person of a menial caste whose family has conducted the pujas at a devasthana for untold generations. In some villages, however, inhabitants share responsibility for the shrine and appoint respected citizens to conduct worship, like the pujari in Mataji’s shrine. Many rituals that take place in a devasthana are conducted by individual devotees without an intermediary. The contact is direct between devotee and Deity.§

Thiruparankundram, Madurai District, Tamil Nadu: Praying for fertility and successful childbirth, a young couple prostrate themselves on the platform of a community shrine in the center of a southern village.

§

Gramadevatas

Occasionally the spirit of community, the Gramadevata, may be transformed into that of another, greater Deity. For example, the essence of the tiny Orissan village of Padmapoda is viewed as the Goddess Gelubai, a local Thakurani, or benign form of the Divine Feminine honored within a sacred tree. Gelubai is believed to protect and nurture every aspect of existence within Padmapoda’s boundaries. At times of great need, however, when an individual, a family, or the entire village requires the aid of Shakti (the dynamic power of the Great Goddess), then a special puja is enacted in which the identity of Gelubai is subsumed into that of the Goddess Chandi. Perhaps someone is particularly ill and is unable to be cured by doctors, or perhaps the village is suffering a drought that endangers its crops and livelihood. In these and other dire cases a special brahmana priest will be hired to perform the puja.§

Gelubai is first bathed, dressed and adorned, as She is every day, and Her usual puja is conducted. Next, an area is cleaned on the platform in front of the tree; a sacred diagram is drawn with special powders, and a fire is laid with sticks of wood. Then the flames are made to flare by being anointed with ghee, during which time the priest sings the names and attributes of the Goddess Chandi. As he extols Her, he places a coconut in the flames and invites the Goddess to pour Her divine energy into the tree, thereby transforming its essence from that of the village into the universal power of the Absolute.§

As the coconut heats, the milk within it boils, causing it to burst, which signals the moment when the transformation is complete. Chandi in all Her strength is then present within the village. Her devotees may have direct darshan with Her. They believe that whatever they pray for will happen, and that by this ritual miracles do occur. The sick person will be healed or the drought ended. Once the puja is complete and the invocations made, Chandi is reverentially thanked and invited to leave the site. The tree returns once more to Gelubai as the village returns to its peaceful farming existence.§

Although the majority of Indian communities worship feminine Gramadevatas, many communities envision these Deities as masculine. In some regions it is common to worship a local form of Rama or Hanuman as Gramadevata. In these cases indigenous legends usually involve the Deity’s interaction with local sites and historical characters that are unique variations of the more common mythology. Many villages refer simply to their God as Baba or Appan (two words for father) or an appellation that incorporates one of these names. Just as Mataji is considered the mother of Lalubhai’s village, in other communities Deities are visualized as judicious and powerful fathers who protect their families from danger.§

Cumbum, Madurai District, Tamil Nadu: Offerings tied in bits of cloth have been fastened to the lateral roots of this pipal tree as a part of prayers to the Goddess Durga. To the upper left is a string of small rolls of paper, each containing the names of the Goddess written in longhand 1,008 times as a gesture of honor.§

In the eastern part of the northern Indian state of Uttar Pradesh, many towns and villages have two Gramadevatas―one masculine, the other feminine―each housed in Its own tree shrine. The local names of these Gods and Goddesses are as varied as their communities, although the generic name for the God is either Baba or Di-Baba, while the Goddess is called Kali-Ma. Both are considered tutelary Deities: they protect their devotees from adversity. Villagers may pray to either or both, depending on inclination and need. An outsider would have difficulty ascertaining the difference between the two tree shrines that honor the God and Goddess, except when terracotta offerings have been made. When devotees request the aid of Di-Baba, it is customary to promise to give Him a terracotta horse when their prayers are answered. If a boon is received, the worshiper will commission this sculpture to be made by a local potter. On a day considered auspicious to the God, the horse will be placed in His devasthana, along with gifts of flowers and food.§

Padmapoda, Puri District, Orissa: Several centuries of daily applications of black oil and red vermilion to one spot on this sacred tree in a small village in eastern India has resulted in a raised lacquer mound that is treated as the face of the Goddess Gelubai. Bangles have been tied as offerings to the Goddess during prayers by women for the health of their families.§

Pujas to Kali-Ma are more popular than those to Di-Baba. Kali-Ma is viewed locally as the Mother Goddess and is petitioned for aid when any kind of problem strikes the family. Her followers may come from any Hindu sect. Her pujas are considered particularly effective in combating agricultural calamities, family crises, civic disputes, infertility and disease. Many believe Her to be both the cause and the cure of smallpox, cholera and measles. When struck with one of these diseases, a person is said to be inhabited by Kali-Ma. Part of the cure is to worship and honor the Goddess within.§

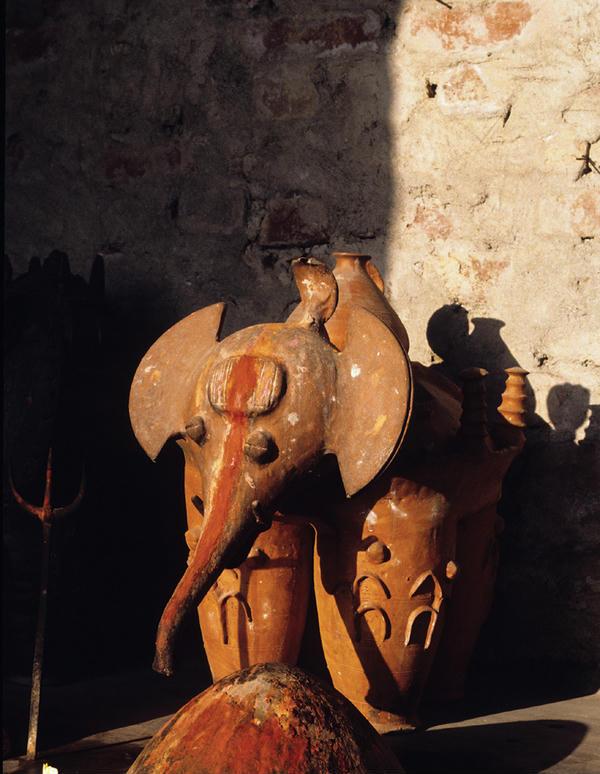

Often the worshiper will promise that if the Goddess answers his or her prayers, then terracotta elephants will be given to Her. These elephants are believed to become real animals in the spirit world the instant they are placed in Her shrine, and many believe that Kali-Ma rides them in Her nightly battles against evil. Once the elephants have been given and transformed by the Goddess, they no longer have any value. They, like the horses given to Di-Baba, remain beneath the tree to disintegrate with the weather, their sole purpose fulfilled.§

Terracotta gifts are placed in the shrines of Gramadevatas throughout India. Most often made on commission by local potters, they are easily affordable, even in a country where the overall per capita income is particularly low. Their form and the style of production vary according to local tradition. Many are simple stick figures made of dowels of clay, others are sculpted of elements thrown on the wheel, while still others are made by coil or slab techniques, or mass-produced in molds. They range in size from just inches high to over sixteen feet, the largest terracottas known in the history of mankind. Almost all are gifts to local Gramadevatas in grateful response to the Deities’ beneficence. Each, even the most elaborate, is ephemeral: its value is in the giving. It represents a personal commitment between the devotee and his or her Deity, the essence of Hindu reciprocity.§

Considering that each Hindu community honors its own individual Gramadevata, it is no wonder that India is said to contain a million and one Gods and Goddesses. The present census lists more than 630,000 villages, not counting the numerous towns and cities. In its entirety, the Hindu pantheon is overwhelming, inconceivable. Its relevance lies in its approachability, not its vastness. Each Hindu has a vital sense of belonging. Each has an Ishtadevata, the Deity of personal choice; a Kuladevata, the Deity of family and household; and a Gramadevata, the Deity of community. An individual’s life is entwined in recognizing and honoring these relationships, in defining the self and one’s interconnectedness to all other living beings. In a world where concepts and values are constantly challenged, the underlying purpose of all the numerous rituals and pujas of every day and season is to allow the Hindu to meet God, an experience that brings with it a sense of clarity, balance and belonging.§

Roopan Devi Oevara, Udaipur District, Rajasthan: Sacred trees are as varied as the communities they represent. Beneath this ancient tree, a large wooden sculpture is carved with multiple images of the Goddess Roopan Devi and with animals associated with Her protection.§

Kushinagar, Deoria District, Uttar Pradesh: This small village shrine contains no image of a Deity. Instead, the simple iron trishula (trident) and the cement pinda (cone) represent the Goddess Kali-Ma. The terracotta elephant, a gift from a grateful devotee, is believed to become a real mount for the Goddess in the spirit world for Her nightly battles against evil.§