PUBLISHER’S DESK • OCTOBER 2009§

The Three Stages of Faith

______________________§

We progress from blind faith to conviction bolstered by philosophy, and finally to certainty forged in the fires of personal experience§

______________________§

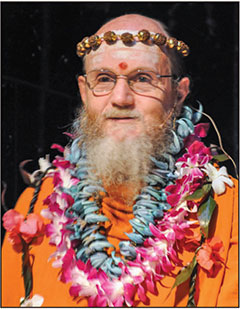

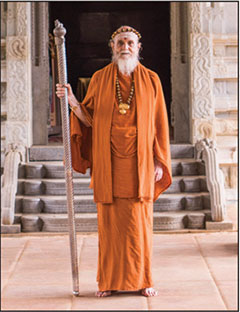

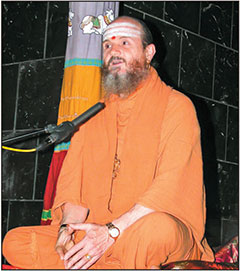

BY SATGURU BODHINATHA VEYLANSWAMI§

FAITH IS CENTRAL TO ALL THE WORLD’S religions. Webster’s dictionary defines religious faith as unquestioning belief in God and religious tenets that does not require proof or evidence. The Hindu view of faith is somewhat different. This is because in Hinduism faith is not a static state; rather, it is constantly deepening through personal experience and growth. The spiritual truths of Sanatana Dharma, initially accepted without proof, are ultimately proved through personal experience. Swami Chinmayananda, founder of Chinmaya Mission, succinctly conveyed this concept: “Faith is to believe what you do not see. The reward of faith is to see what you believed.”§

FAITH IS CENTRAL TO ALL THE WORLD’S religions. Webster’s dictionary defines religious faith as unquestioning belief in God and religious tenets that does not require proof or evidence. The Hindu view of faith is somewhat different. This is because in Hinduism faith is not a static state; rather, it is constantly deepening through personal experience and growth. The spiritual truths of Sanatana Dharma, initially accepted without proof, are ultimately proved through personal experience. Swami Chinmayananda, founder of Chinmaya Mission, succinctly conveyed this concept: “Faith is to believe what you do not see. The reward of faith is to see what you believed.”§

My Gurudeva, Sivaya Subramuniyaswami, presents this deeper aspect of faith by citing an old saying favored by pragmatic intellectuals, “Seeing is believing,” and then states that a more profound adage is “Believing is seeing.” He goes on to explain that today’s scientists and educators see with their two eyes and pass judgments based on what they currently believe. The rishis of the past and the rishis of the now and those yet to come also are seers. Their seeing is not with the two eyes; it is with the third eye, the eye of the soul. Gurudeva observed, “The intellect in its capacity to contain truth is a very limited tool, while faith is a very broad, accommodating and embracing faculty. The mystery of life and beyond life, of Siva, is really better understood through faith than through intellectual reasoning.”§

The focus of many religions is on helping those with no faith in God to believe in God. For Western faiths, belief in God is the beginning and the end of the process. Once you have come to believe in God, there is nothing more to do. Your salvation is assured. However, in Hinduism belief is only the first step. Hindus want to move beyond just believing in God to experiencing the Divine for themselves.§

Faith, called astikya in Sanskrit, is the fourth of ten spiritual practices called niyamas, literally meaning “to unleash.” The niyamas are ethical and religious practices that release or cultivate one’s refined, soul qualities. These observances comprise the second limb of the ashtanga (“eight-limbed”) yoga system, which is codified in numerous scriptures.§

Gurudeva summarizes faith as a Hindu practice: “Astikya is to cultivate an unshakable faith. Believe firmly in God, Gods, guru and your path to enlightenment. Trust in the words of the masters, the scriptures and traditions. Practice devotion and sadhana to inspire experiences that build advanced faith. Be loyal to your lineage, one with your satguru. Shun those who try to break your faith by argument and accusation. Avoid doubt and despair.”§

Like faith, the world’s creation is addressed in all religions. A common Hindu view is that God creates and is His creation. This panentheistic vision contrasts with other religious views, such as “creation out of nothing” and “non-creation,” the view that reality is beginningless and eternal. The Hindu view of God’s creating the world from Himself is described in the Mundaka Upanishad: “As a spider spins and withdraws its web, as herbs grow on the earth, as hair grows on the head and body of a person, so also from the Imperishable arises this universe.”§

Examining these concepts of faith and creation together enables us to make an interesting comparison between the perspectives of a modern scientist and a Hindu sage. The scientist’s natural question is, “How can you prove the existence of God?” The sage’s natural rejoinder is, “How can you deny the existence of God?” This polarity arises from the fact that everything the scientist perceives is matter, and everything the sage sees is God.§

The cultivation of faith can be compared to the growth of a tree. As a young sapling, it can easily be uprooted, just as faith based solely on belief can easily be shaken or destroyed. Faith bolstered with philosophical knowledge is like a medium-size tree, strong and not easily disturbed. Faith matured by personal experience of God and the Gods is like a full-grown tree which can withstand external forces. Let’s look more closely at faith’s three developmental stages.§

Blind Faith: Faith in its initial stage is simple belief without the support of either knowledge or experience. Keeping our faith strong in this phase depends heavily on the company we keep. We need to associate with spiritual companions and avoid worldly and nonreligious people. Attending a weekly satsang with like-minded devotees is sustaining. Having the darshan of visiting swamis and other Hindu religious leaders helps keep our faith strong, as we see them as living examples, souls who know from experience the principles we believe in.§

Informed Conviction: Faith in its second stage is belief strengthened by a sound understanding of Hindu philosophy. Gurudeva called this the bedrock on which faith is sustained. It is established by studying in a systematic and consistent manner to increase your knowledge about Hindu philosophy and practices. Such a study can include comparing Hinduism with the world’s other major religions to understand how they differ and how they are similar.§

Personal Realization: In the third stage of faith, personal experience transforms informed conviction into certainty. Gurudeva refers to this inner knowing as advanced faith, established by one’s own spiritual, unsought-for, unbidden revelations, visions or flashes of intuition, which one remembers even stronger as the months go by, more vividly than something read from a book, seen on television or heard from a friend or a philosopher. Gurudeva stresses that spiritual experiences—when verified by what yogis, rishis and sadhus have seen and heard and whose explanations centuries have preserved—create a new, superconscious intellect. This type of faith, more a knowing than a conviction, is unshakable.§

As we evolve spiritually, faith matures. I have seen so many devotees growing into a deeper relationship with God, a more profound acceptance of Divinity in their lives. Here are some examples.§

First Example: A girl attends the local temple weekly with her parents but never thinks much about Hindu beliefs and practices. As a teenager, she enjoys reading books about holy men and women, the stories of their lives and their wise sayings. The experience of these great souls noticeably deepens her conviction in the precepts she was taught at the temple as a child.§

Second Example: A young man attends an upadesha by a visiting swami whose presence is radiant with spiritual light. His talk increases the seeker’s faith and inspires him to intensify his religious practices.§

Third Example: While worshiping at an ancient shrine to Lord Ganesha during a pilgrimage to Sri Lanka, a man has a life-altering vision. The Lord of Obstacles walks out of the shrine and stands before him, giving blessings, then walks back into the shrine. This dramatic experience convinces him, through and through, that the Gods are real.§

Fourth Example: A woman meditates every morning, but her thinking always distracts her and she never goes deeply within. One morning, for no apparent reason, distractions recede and she finds herself going in and in and in and staying in an expansive, peaceful state for a long time. Returning to normal awareness, she sees life differently, holding a new perspective that God is a consciousness permeating all, and she is that consciousness. The belief that the soul and God are one takes on new meaning to her.§

Fifth Example: A faith-building experience that many Hindus shared occurred in 1995. It all began when one man in New Delhi had a dream that Ganesha craved a little milk. In the early morning he went to a temple where a priest allowed him to offer a spoonful of milk to the small stone image. Both watched in astonishment as the milk disappeared. Within hours news had spread across India that Ganesha was accepting milk offerings. Tens of millions of people of all ages flocked to temples across the globe and had the same experience. A Reuters report quoted Anila Premji: “I held the spoon out level, and it just disappeared. To me it was a miracle. It gave me a feeling that there is a God, a sense of Spirit on this Earth.”§

An important aspect of deepening our faith is building confidence in our innate divinity and our ability to experience it. We are fortunate in the modern Hindu world to have enlightened men and women in whom we can recognize high spiritual attainments. In them we have living examples of the illumined state we hope to one day achieve. We must remember that their attainment is our own potential; it is, in fact, the spiritual destiny of each soul in this or a future life. The path to such attainment involves regular practice of devotion and meditation, which leads eventually to personal experiences of the Divine.§

PUBLISHER’S DESK • JANUARY 2011§

Practice Makes Perfect

______________________§

Five core disciplines for bringing our inner perfection into our intellectual, emotional and instinctive nature§

______________________§

BY SATGURU BODHINATHA VEYLANSWAMI§

“PRACTICE MAKES PERFECT” IS CERTAINLY A commonly used phrase. Normally it refers to how we can acquire a skill that we do not have. For example, let’s say we type twenty words a minute with two index fingers. We make a decision to improve that skill and attend a typing class for six months, practicing every day. We master the skill of typing with all ten fingers, without looking at the keyboard, at an average speed of fifty words a minute! Our practice made our typing more perfect. When this concept is applied to efforts in our spiritual life, it takes on a different meaning. This is because our inner essence, our soul nature, is already perfect. Our practice, or self effort, is to bring that inner perfection into our outer intellectual, emotional and instinctive nature. Thus we could modify the adage to be “practice manifests perfection.”§

“PRACTICE MAKES PERFECT” IS CERTAINLY A commonly used phrase. Normally it refers to how we can acquire a skill that we do not have. For example, let’s say we type twenty words a minute with two index fingers. We make a decision to improve that skill and attend a typing class for six months, practicing every day. We master the skill of typing with all ten fingers, without looking at the keyboard, at an average speed of fifty words a minute! Our practice made our typing more perfect. When this concept is applied to efforts in our spiritual life, it takes on a different meaning. This is because our inner essence, our soul nature, is already perfect. Our practice, or self effort, is to bring that inner perfection into our outer intellectual, emotional and instinctive nature. Thus we could modify the adage to be “practice manifests perfection.”§

Swami Ranganathananda (1908-2005) of the Ramakrisha Math and Mission expressed this idea beautifully in an article we published in 1999 on medical ethics. He stated that the Hindu view of man “is that his essential, real nature is the atman or Self, which is immortal, self-luminous, the source of all power, joy and glory. Everything that helps in the manifestation of the divinity of the soul is beneficial and moral, and everything that obstructs this inner unfoldment is harmful and immoral.”§

Satguru Sivaya Subramuniyaswami, founder of HINDUISM TODAY, gave a succinct description of our divine nature: “Deep inside we are perfect this very moment, and we have only to discover and live up to this perfection to be whole. We have taken birth in a physical body to grow and evolve into our divine potential. We are inwardly already one with God. Our religion contains the knowledge of how to realize this oneness and not create unwanted experiences along the way.”§

In giving talks on the idea of how we can grow and evolve into our divine potential, I frequently use the analogy of dance. I ask the audience, “What is most needed for a youth to become good at Hindu classical dance?” Invariably, many state the answer that I have in mind: “Practice!” Reading books about dance won’t make you a good dancer. Nor will attending classes without practicing what you have learned. Regular practice is needed to make the body limber and master the many movements, positions, gestures and expressions. Likewise, to grow and evolve into our divine potential—to manifest our inner perfection in our outer intellectual and instinctive nature—requires regular practice.§

A core practice that I recommend focusing on first is daily worship in the home shrine, preferably before dawn. Every Hindu home should have a place of worship. It may be as simple as a shelf with pictures of God or it can be an entire room dedicated to worship and meditation. Many families have a spiritual guide or guru and display his or her picture in the shrine. If you are living away from home, such as at a university, a single photo may have to do. In this sacred space we light a lamp, ring a bell and pray daily. The most devout hold a formal worship ritual, or atmartha puja. This regular daily worship is called upasana. Residents go to the shrine for blessings before leaving for work or school. At other times one may sit in the shrine to pray, chant the names of God, sing devotional songs, read from scripture or meditate. The home shrine is also an excellent place to re-center oneself through prayer and reflection when emotionally upset.§

A second expression of Hindu worship is utsava, holy days, observing the same day each week as a holy day and celebrating the major festival days through the year. On their weekly holy day, the family clean and decorate the home altar, attend the nearby temple and observe a fast. To make such weekly visits practical, Hindus seek to live within a day’s journey of a temple. Those who do not live close enough to a temple to visit weekly go as often as they can and do their best to attend the major festivals.§

The temple is a sacred building, revered as the home of God. This is because of its mystical architecture, consecration and the continuous daily worship, or puja, performed thereafter. Puja is performed by qualified priests, invoking the Deity by chanting Sanskrit verses from scripture and making successive offerings which conclude with arati—the waving of an oil lamp in front of the Deity while bells are rung loudly. The Deity image, or murti, is especially sacred. It is through the murti that the presence and power of the Deity is felt by devotees who attend the puja for blessings and grace.§

A third expression of Hindu worship is pilgrimage, or tirthayatra. At least once each year, a journey is made for darshan of holy persons, temples and places, ideally away from one’s local area. During this sojourn, God, Gods and gurus become the singular focus of life. All worldly matters are set aside. Thus pilgrimage provides a complete break from one’s usual day-to-day concerns. Special prayers are kept in mind, and penance or some form of sacrifice is part of the process. Actually, the preparation is as important as the pilgrimage itself. In the days or weeks before a tirthayatra, devotees perform spiritual disciplines such as decreasing the intake of heavier foods while increasing lighter foods, fasting one day a week, reading from scripture each night before sleep, and on weekends doubling the time usually spent in religious practices. These three forms of worship—daily puja, holy days and pilgrimage—help us to manifest our inner perfection in our outer nature.§

A fourth aspect of Hinduism that can be embraced as a core practice is dharma, or virtuous living, living an unselfish life of duty and good conduct, which includes atoning for misconduct. One learns to be selfless by thinking of others first, being respectful to parents, elders and swamis, following divine law—especially ahimsa, which is mental, emotional and physical noninjuriousness toward all beings. An important focus for upholding dharma is to uphold the ten ethical restraints, or yamas. The first restraint, ahimsa, is the foremost. The others are: satya, truthfulness; asteya, nonstealing; brahmacharya, sexual purity; kshama, patience; dhriti, steadfastness; daya, compassion; arjava, honesty, straightforwardness; mitahara, moderate appetite and vegetarianism; and shaucha, purity.§

Our fifth practice is the observance of traditional rites of passage, called samskaras. At these crucial ceremonies, an individual receives the blessings of God, Gods, guru, family and community as he or she commences a new phase of life. The first major samskara is namakarana, the name-giving rite, which also marks formal entry into a particular sect of Hinduism. It is performed 11 to 41 days after birth. At this time, guardian devas are assigned to see the child through life. Annaprashana, the first feeding of solid food, is held at about six months. Vidyarambha marks the beginning of formal education, when a boy or girl ceremoniously writes the first letter of the alphabet in a tray of uncooked rice. Vivaha is the rite of marriage, an elaborate and joyous ceremony in which the homa fire is central. Antyeshti, the funeral rite, guiding a soul in its transition to inner worlds, includes preparation of the body, cremation, bone-gathering, dispersal of ashes and home purification.§

These five practices are referred to as the pancha nitya karmas, “five eternal practices,” by Satguru Sivaya Subramuniyaswami, who notes, “We could say that they are an amalgam of all the counsel of the Vedas and Agamas to guide daily and yearly religious life. These five obligatory religious practices are simple and applicable for all. Study them and put them into practice in your own life.”§

Upasana, worship§

Upasana, worship§

Utsava, holy days§

Utsava, holy days§

Tirthayatra, pilgrimage§

Tirthayatra, pilgrimage§

Dharma, virtuous living§

Dharma, virtuous living§

Samskaras, sacraments§

Samskaras, sacraments§

These five duties, faithfully performed, are powerful tools to help us grow and evolve into our divine potential. Many Hindus go one step further in their striving by receiving initiation, known as diksha, from a qualified priest or guru. Mantra diksha is the primary initiation, the empowerment of a specific mantra as a personal sadhana, and the assignment to chant it as a daily practice for a minimum number of repetitions, such as 108. A second diksha is initiation to perform a specific form of puja, and the commitment to perform it daily in the home shrine.§

In Hinduism, it is not enough to just be—or to wait for grace. The most devout know that each life on Earth is an opportunity for advancement and therefore take advantage of the many tools their faith provides. Following these five traditional observances brings forth, day by day, the perfection that lies waiting within each of us.§

PUBLISHER’S DESK • JANUARY 2003§

Mistakes Are Part of the Spiritual Path

______________________§

Blunders are, in truth, opportunities to improve our behavior and thereby make spiritual progress§

______________________§

BY SATGURU BODHINATHA VEYLANSWAMI§

SINCE SEPTEMBER 11, THERE HAVE BEEN increased statements by Western leaders condemning some men as being evil and extolling others as being good. This, of course, is not the Hindu perspective. But since it is so common, it is good to take time to reflect on the Hindu point of view regarding good and evil. For those who are parents it is good to discuss the Hindu view with their children, to make sure our and our children’s thinking on the matter remains uninfluenced by Western thought.§

SINCE SEPTEMBER 11, THERE HAVE BEEN increased statements by Western leaders condemning some men as being evil and extolling others as being good. This, of course, is not the Hindu perspective. But since it is so common, it is good to take time to reflect on the Hindu point of view regarding good and evil. For those who are parents it is good to discuss the Hindu view with their children, to make sure our and our children’s thinking on the matter remains uninfluenced by Western thought.§

The Hindu viewpoint is that all of mankind is good, for we are all divine beings, souls created by God. In fact, we are all one family, “Vasudhaiva kutumbakam—the whole world is one family.” Each soul is emanated from God, as a spark from a fire, on a spiritual journey which eventually leads back to God. All human beings are on this journey, whether they realize it or not, and the journey spans many lives.§

If all are on the same journey, why is there such a disparity between men? Clearly, some act like saints and others act like sinners. Some take delight in helping their fellow men, while others delight in harming them. The Hindu explanation is that each of us started the journey at a different time. Thus some are at the beginning of the spiritual path, while others are near the end. In other words, there are young souls and there are old souls. Our paramaguru, Jnanaguru Siva Yogaswami, in speaking to devotees, described life as a school, with some in the M.A. class and others in kindergarten, and to each he gave lessons according to the level of advancement.§

Man’s nature can be described as threefold: spiritual, intellectual and instinctive. It is the instinctive nature, the animal-like nature, which contains the tendencies to harm others. Men who are expressing those tendencies are young souls who need to learn to harness this force. The Hindu approach to such a man is not to label him evil, but rather to focus on helping him learn to control his instincts and improve his behavior. Gurudeva, Satguru Sivaya Subramuniyaswami, said insightfully: “People act in evil ways who are not yet in touch with their soul nature and live totally in the outer, instinctive mind. What the ignorant see as evil, the enlightened see as the actions of low-minded and immature individuals.”§

Important insights into the soul’s maturing process can be gained by looking at the three shaktis of God Siva—iccha, the power of desire; kriya, the power of action; and jnana, the power of wisdom—which are also the three powers of the soul. We first have a desire, and when the desire becomes strong enough, we act. In young souls the action may be ill conceived, even against dharma. For example, a man wants a computer, so he steals one. Money is needed, so he robs a bank. The soul is often caught up in repeating a cycle of similar experiences, moving back and forth from desire to action, desire to action, until the needed lesson is learned. In the case of the adharmic action of stealing, eventually he will learn the lesson that this is not the best way to acquire possessions. This learning is the jnana shakti, wisdom, causing his behavior to improve.§

This process is the same for dharmic actions. Say we are helping out as a volunteer at the temple, teaching children’s classes once a month. We like the feeling of helping others in a meaningful way and so decide to help out every week and even participate in regular meetings to plan the classes. We are doing a selfless action, and the reaction it has on us is to feel more inner joy. The jnana is to resolve to do even more service and thus feel more joyful. We have improved our behavior.§

A recent segment on television described an innovative prison in California. As we all know, the usual approach is to regard jail simply as a time punishment by confinement for a number of years. Under this approach, many of the prisoners released repeat the same crimes and return to jail again and again. Their behavior shows no improvement. In fact, they may learn the criminal’s craft while serving their sentence. In this innovative prison program, the warden had initiated a regimen that included counseling, yoga and other therapeutic activities to improve the behavior of prisoners so they would not repeat their crimes and return to jail. The program is showing an excellent success rate.§

For all of mankind, no matter where one is on the path, spiritual advancement comes from improving one’s behavior. Said another way, it comes from learning from one’s mistakes. Unfortunately, this process is often inhibited by the idea that somehow we are not supposed to make mistakes, that mistakes are bad. We grow up being scolded for our mistakes by our parents. Teachers ridicule students when they make mistakes. Supervisors yell at workers when they make a mistake. No wonder many adults feel terrible when they make a mistake. To spiritually benefit from our mistakes, we need a new attitude toward them. Gurudeva described mistakes as “wonderful opportunities to learn.” He compared learning from life’s experiences to progressing through the classes at a university. He proclaimed: “Life is a series of experiences, one after another. Each experience can be looked at as a classroom in the big university of life if we only approach it that way. Who is going to these classrooms? Who is the member of this university of life? It’s not your instinctive mind. It’s not your intellectual mind. It’s the body of your soul, your superconscious self, that wonderful body of light. It’s maturing under the stress and strain.”§

Those who are parents can teach their children that making mistakes is not bad. Everyone makes mistakes. It is natural, and simply shows we do not understand something about the matter at hand, or we have been inattentive. It is important for parents to determine what understanding the child lacks and teach it to him without blame or shame. When parents discipline through natural and logical consequences, children are encouraged to learn to reflect on the possible effects of their behavior before acting. Such wisdom can be nurtured through encouraging self-reflection, asking the child to think about what he did and how he could avoid making that mistake again.§

A common first reaction to having made a mistake is to become upset, to become fretful or angry about it, or if it is a serious mistake to become deeply burdened and even depressed. That is a natural first reaction, but if it is our only reaction, it is not enough. To progress, we need to cope with the emotional reaction to the action and move on to the learning stage.§

A good second reaction to a mistake is to think clearly about what happened, why it occurred and find a way to not repeat the mistake in the future. Perhaps we were not being careful enough, and simply resolving to be more circumspect next time will prevent the problem from recurring. Perhaps we lacked some important knowledge, and now we have that knowledge, which we can simply resolve to use next time.§

Perhaps we created unintended consequences that caused significant problems to us or others. Now that we are aware of the consequences, we certainly won’t repeat the action. Those who are striving to live a spiritual life are self-reflective and learn quickly from their blunders. In fact, one way to tell a young soul from an old soul is to observe how quickly he cognizes his error and learns not to repeat the same mistake.§

A third remedy may be needed if the misstep involved other people. Perhaps we have hurt someone’s feelings or created a strain between us. A direct apology can fix this if we know them well. If we are not close enough to the individual to be able to apologize, a generous act toward them can often adjust the flow of feelings back into a harmonious condition. For example, hold a small dinner party and include them among the guests.§

A fourth remedy may be needed if one commits a major misdeed: for example, if we did something that was dishonest. Even if we have resolved to not repeat the misdeed and apologized to those involved, we may still feel guilty about the transgression. By performing some form of penance, prayashchitta, we can rid ourselves of the sense of feeling bad about ourself. Typical forms of penance are fasting, performing 108 prostrations before the Deity or walking prostrations up a sacred path or around a temple.§

All of this does not mean we don’t punish those who act in evil ways. Societies and nations must protect themselves with appropriate actions that restrain wrongful behaviors. But even while punishing those who act with malicious intent, let us remember they, too, are souls on the journey of spiritual maturity and discovery. Let the focus be not on categorizing men as good or evil but on encouraging all to improve their behavior, by applying the appropriate remedies and sanctions.§

PUBLISHER’S DESK • OCTOBER 2006§

Lessons from a Simple Sage

______________________§

How a devotee received two potent teachings from Yogaswami of Sri Lanka: “We know nothing” and “Know thy Self”§

______________________§

BY SATGURU BODHINATHA VEYLANSWAMI§

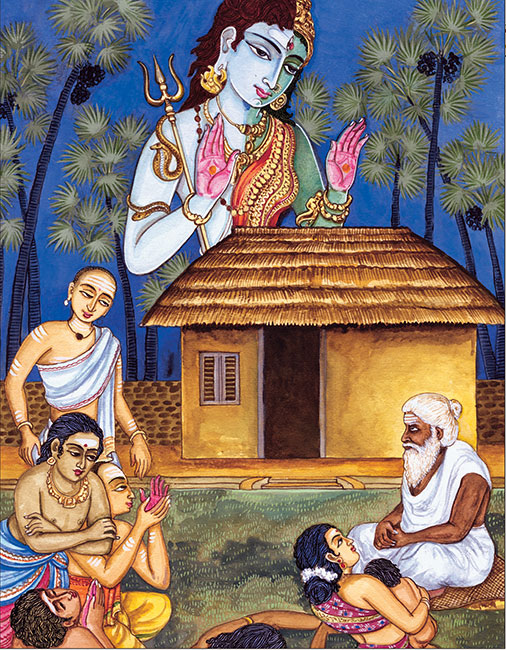

SOMETIME AROUND 1955, TWO DEVOUT hindus visited my guru’s guru, an illumined master, Satguru Yogaswami of Sri Lanka. In that encounter they received a potent dose of the sage’s teachings about the spiritual path. One of them recorded their experience as follows. “It was a cool and peaceful morning, except for the rattling noises owing to the gentle breeze that swayed the tall and graceful palmyra trees. We walked silently through the narrow and dusty roads. The city was still asleep. Yogaswami lived in a tiny hut that had been specially constructed for him in the garden of a home outside the city of Jaffna. The hut had a thatched roof and was on the whole characterized by the simplicity of a peasant dwelling. Yogaswami appeared exactly as I had imagined him to be. At 83 he looked very old and frail. He was of medium height, and his long grey hair fell over his shoulders. When we first saw him, he was sweeping the garden with a long broom. He slowly walked towards us and opened the gates.§

SOMETIME AROUND 1955, TWO DEVOUT hindus visited my guru’s guru, an illumined master, Satguru Yogaswami of Sri Lanka. In that encounter they received a potent dose of the sage’s teachings about the spiritual path. One of them recorded their experience as follows. “It was a cool and peaceful morning, except for the rattling noises owing to the gentle breeze that swayed the tall and graceful palmyra trees. We walked silently through the narrow and dusty roads. The city was still asleep. Yogaswami lived in a tiny hut that had been specially constructed for him in the garden of a home outside the city of Jaffna. The hut had a thatched roof and was on the whole characterized by the simplicity of a peasant dwelling. Yogaswami appeared exactly as I had imagined him to be. At 83 he looked very old and frail. He was of medium height, and his long grey hair fell over his shoulders. When we first saw him, he was sweeping the garden with a long broom. He slowly walked towards us and opened the gates.§

“ ‘I am doing a coolie’s job,’ he said. ‘Why have you come to see a coolie?’ He chuckled with a mischievous twinkle in his eyes. I noticed that he spoke good English with an impeccable accent. As there is usually an esoteric meaning to all his statements, I interpreted his words to mean this: ‘I am a spiritual cleanser of human beings. Why do you want to be cleansed?’§

“He gently beckoned us into his hut. Yogaswami sat cross-legged on a slightly elevated neem-wood platform and we sat on the floor facing him. We had not yet spoken a single word. That morning we hardly spoke; he did all the talking.§

“Yogaswami closed his eyes and remained motionless for nearly half an hour. He seemed to live in another dimension of his being during that time. One wondered whether the serenity of his facial expression was attributable to the joy of his inner meditation. Was he sleeping or resting? Was he trying to probe into our minds? My friend indicated with a nervous smile that we were really lucky to have been received by him. Yogaswami suddenly opened his eyes. Those luminous eyes brightened the darkness of the entire hut. His eyes were as mellow as they were luminous—the mellowness of compassion.§

“I was beginning to feel hungry and tired, and thereupon Yogaswami asked, ‘What will you have for breakfast?’ At that moment I would have accepted anything that was offered but I thought of idly (steamed rice cakes) and bananas, which were popular food items in Jaffna. In a flash there appeared a stranger in the hut who respectfully bowed and offered us these items of food from a tray. A little later my friend wished for coffee, and before he could express his request in words the same man reappeared on the scene and served us coffee.§

“After breakfast, Yogaswami asked us not to throw away the banana skins, which were for the cow. He called loudly to her and she clumsily walked right into the hut. He fed her the banana skins. She licked his hand gratefully and tried to sit on the floor. Holding out to her the last banana skin, Yogaswami ordered, ‘Now leave us alone. Don’t disturb us, Valli. I’m having some visitors.’ The cow nodded her head in obeisance and faithfully carried out his instructions.§

“Yogaswami closed his eyes again, seeming once more to be lost in a world of his own. I was indeed curious to know what exactly he did on these occasions. I wondered whether he was meditating. There came an apropos moment to broach the subject, but before I could ask any questions he suddenly started speaking.§

“ ‘Look at those trees. The trees are meditating. Meditation is silence. If you realize that you really know nothing, then you would be truly meditating. Such truthfulness is the right soil for silence. Silence is meditation.’§

“He bent forward eagerly. ‘You must be simple. You must be utterly naked in your consciousness. When you have reduced yourself to nothing—when your self has disappeared, when you have become nothing—then you are yourself God. The man who is nothing knows God, for God is nothing. Nothing is everything. Because I am nothing, you see, because I am a beggar, I own everything. So nothing means everything. Understand?’ “§

“ ‘Tell us about this state of nothingness,’ requested my friend with eager anticipation. ‘It means that you genuinely desire nothing. It means that you can honestly say that you know nothing. It also means that you are not interested in doing anything about this state of nothingness.’§

“What, I speculated, did he mean by ‘know nothing?’ The state of ‘pure being’ in contrast to ‘becoming?’ He responded to my thought, ‘You think you know but, in fact, you are ignorant. When you see that you know nothing about yourself, then you are yourself God.’ “§

This narrative reveals a vital theme in Yogaswami’s teachings: esoteric insights about nothingness and not knowing. In life, the normal emphasis is on acquiring knowledge, or replacing a lack of knowledge on a subject with knowledge. For example, we purchase a new computer. Knowing little about it, we read the manuals, talk to experts and end up acquiring enough information to use the computer. We have replaced a lack of knowledge with knowledge.§

Yogaswami’s approach, because it deals with spiritual matters, is the opposite. We start with intellectual knowledge about God and strive to rid ourselves of that knowledge. When we succeed, we end up experiencing God. Why is this? Because the intellect cannot experience God. The experience of God in His personal form and His all-pervasive consciousness lies in the superconscious or intuitive mind. And, even more cryptic, the experience of God as Absolute Reality is beyond even the superconscious mind.§

Yogaswami once expressed it to a seeker in this stern phrase: “It’s not in books, you fool.” Acquiring clear intellectual concepts of the nature of God is good, but these concepts must be eventually transcended to actually experience God.§

One of the great sayings of Yogaswami’s guru, Chellappaswami, emphasizes the same idea. He said, “Naam ariyom,” which translates as, “We do not know.” My own guru expressed the same idea in this aphorism: “The intellect strengthened with opinionated knowledge is the only barrier to the superconscious.” He went on to explain that “a mystic generally does not talk very much, for his intuition works through reason, but does not use the processes of reason. Any intuitive breakthrough will be quite reasonable, but it does not use the processes of reason. Reason takes time. Superconsciousness acts in the now. All superconscious knowing comes in a flash, out of the nowhere. Intuition is more direct than reason, and far more accurate.”§

Thus, three gurus of our Kailasa Parampara have each expressed the truth that experience of God is possible only when we transcend the limited faculties of our intellect and the concepts it has about God and dive deeply into our superconscious, intuitive mind and beyond. Said another way, the experience of emptying ourselves of our intellectual concepts about God needs to precede filling ourselves with the experience of God’s holy presence within us.§

To guide us on the path to this experience, Yogaswami stressed the importance of meditation and formulated a key teaching, or mahavakya, which is: Tannai ari, or “Know thyself.” This is a second dominant theme of his teachings. He proclaimed, “You must know the Self by the self. Concentration of mind is required for this…. You lack nothing. The only thing you lack is that you do not know who you are.… You must know yourself by yourself. There is nothing else to be known.”§

Markanduswami, a close devotee of Yogaswami, would later tell me, “Yogaswami didn’t give us a hundred-odd works to do. Only one. Realize the Self yourself, or know thy Self, or find out who you are.” What, exactly, does it mean to know thy Self? Yogaswami explains beautifully in one of his published letters: “You are not the body; you are not the mind, nor the intellect, nor the will. You are the atma. The atma is eternal. This is the conclusion at which great souls have arrived from their experience. Let this truth become well impressed on your mind.”§

Today we are overwhelmed by information. Books, television and the Internet deluge us with vast seas of information never before available. Though information abounds, how much of it is teaching us about spirituality, that we are a divine soul? Unfortunately, only a miniscule amount. Most information in our modern world teaches us to identify with our external nature. Movies and TV teach us that we are our body and emotions, and in school we are taught that we are our intellect. For today’s world, we need to amplify Yogaswami’s saying to read, “It’s not in books, television, movies, the Internet or computer games, you fool!” Yogaswami knew most people are trepidatious about meditating deeply, diving into their deepest Self, and gave assurance that inner and outer life are compatible by saying, “Leave your relations downstairs, your will, your intellect, your senses. Leave the fellows and go upstairs by yourself and find out who you are. Then you can go downstairs and be with the fellows.”§

We all, of course, recognize the high spiritual attainments of Hinduism’s great yogis and satgurus. However, it is equally important to understand that their attainments are also our potential, the spiritual destiny of each soul, to be reached at some point in this or a future life. The mission of their lives is truly fulfilled if their example inspires you to devote more time and dedication to your own spiritual practices.§