PUBLISHER’S DESK • JULY 2012§

Which Yoga Should I Follow?

______________________§

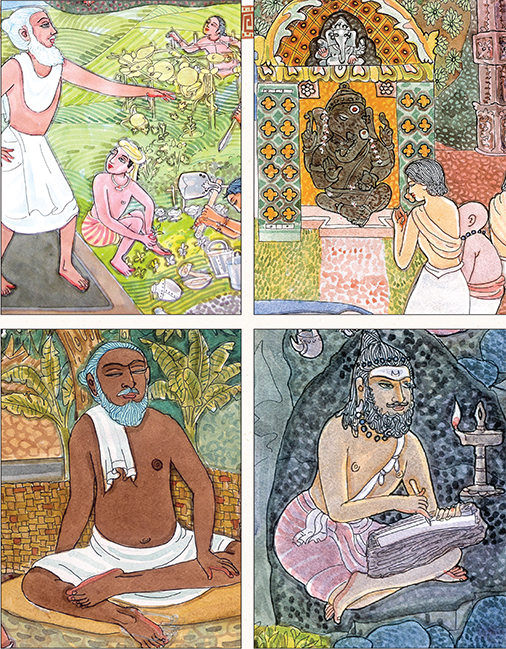

Exploring four popular approaches to four spiritual regimens: karma yoga, bhakti yoga, raja yoga and jnana yoga§

______________________§

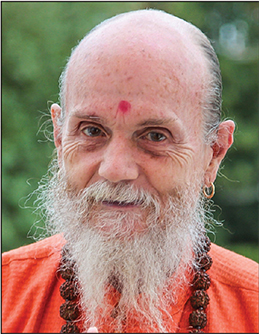

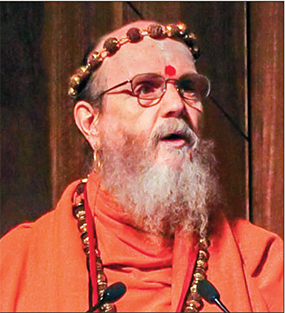

BY SATGURU BODHINATHA VEYLANSWAMI§

IN MODERN HINDU TEXTS, THE MOST COMMON summary of Hindu spiritual practice is the system of four yogas: karma (action), bhakti (devotion), raja (meditation) and jnana (knowledge). Let’s start with a short description of each and then ponder the question, “Which yoga or yogas should I pursue at this time?”§

IN MODERN HINDU TEXTS, THE MOST COMMON summary of Hindu spiritual practice is the system of four yogas: karma (action), bhakti (devotion), raja (meditation) and jnana (knowledge). Let’s start with a short description of each and then ponder the question, “Which yoga or yogas should I pursue at this time?”§

Karma yoga is the path of action. It begins with refraining from what should not be done. Next we seek to renounce actions motivated solely by selfish desires, those actions that benefit only ourselves. Then comes the desire to conscientiously fulfill our duties in life. An important aspect of karma yoga is performing selfless service to help others. When we are successful, our work is transformed into worship. My paramaguru, Yogaswami of Sri Lanka, captured the essence of this ideal when he said, “All work must be done with the aim of reaching God.”§

Bhakti yoga is the path of devotion to and love of God. Practice focuses on listening to stories about God, singing devotional hymns, pilgrimage, intoning a mantra and worshiping in temples and one’s home shrine. The fruition of bhakti yoga is an ever-closer rapport with the Divine, developing qualities that make communion possible—love, selflessness and purity—eventually leading to prapatti, self-effacement and total surrender to God. My guru, Sivaya Subramuniyaswami, gave this insightful description: “God is love, and to love God is the pure path prescribed in the Agamas (a category of revealed scripture). Veritably, these texts are God’s own voice admonishing the samsari, reincarnation’s wanderer, to give up love of the transient and adore instead the Immortal. How to love the Divine, when and where, with what mantras and visualizations and at what auspicious times, all this is preserved in the Agamas.”§

Raja yoga is the path of meditation. It is a system of eight progressive stages of practice: ethical restraints, religious observances, posture, breath control, withdrawal, concentration, meditation and enstasy, or mystic oneness. The focus is on restraining the modifications of the mind so that our awareness—which usually takes on the forms of the mind’s modifications—can abide in its essential form. The restraint of these modifications is achieved through practice and detachment. My guru used the term consciousness to explain the modifications of the mind: “Consciousness and awareness are the same when awareness is totally identified with and attached to that which it is aware of. To separate the two is the artful practice of yoga.”§

Jnana yoga is the path of knowledge. It involves philosophical study and discrimination between the Real and the unreal. Though the word jnana is derived from the verbal root jñâ, which simply means knowing, it has a higher philosophical connotation. It is not only intellectual knowledge but also intuitive experience. It starts with the former and ends with the latter. Jnana yoga consists of three progressive practices: shravana (listening to scripture); manana—thinking and reflecting; and nididhyasana—constant and profound meditation. Four great sayings from the Upanishads are often the subject of reflection: “Consciousness is Brahman;” “That thou art;” “This Self is Brahman;” and “I am Brahman.” Swami Chinmayananda, founder of Chinmaya Mission, taught: “The goal of jnana yoga is, through discrimination, to differentiate between the Real and the unreal and finally come to realize one’s identity with the Supreme Reality.”§

Having looked in brief at each of the four primary yogas, let’s focus on how they are approached in various schools of thought. This may help you to choose the yoga (or yogas) that is right for you to practice at this state of your spiritual unfoldment.§

The first and most widely known approach is to choose one of the yogas based on your temperament. The Vedanta Society of Southern California puts forth this approach on its website: “Spiritual aspirants can be broadly classified into four psychological types: the predominantly emotional, the predominantly intellectual, the physically active, the meditative. There are four primary yogas designated to ‘fit’ each psychological type.” In this approach, bhakti yoga is recommended for the predominantly emotional, jnana yoga for the intellectual, karma yoga for the physically active and raja yoga for the meditative person. §

However, it is sometimes advised that seekers who are intellectually inclined should stay away from jnana yoga. Linda Johnson explains this in her book Hinduism for Idiots. “Think you’re smart? Surprisingly, Hindu gurus often advise bright people to take up the path of devotion, not jnana yoga. That’s because very intelligent people often benefit more by learning to open their hearts. Jnana yoga is not so much for intellectuals as for people with a strongly developed mystical sense and a burning desire for the actual experience of God Realization.”§

A second approach is to choose one of the yogas as your primary focus based on your temperament but to also practice the other three yogas in a secondary way. Swami Sivananda, founder of the Divine Life Society, maintained that though seekers naturally gravitate toward one path, the lessons of each of the paths must be integrated by every seeker if true wisdom is to be attained. The motto of his organization is, “Serve, Love, Meditate, Realize,” referring respectively to the four yogas: karma, bhakti, raja and jnana.§

A third approach emphasizes that one or another of the four yogas is the highest path and should be followed by everyone. It is common for Vaishnava organizations to put forth bhakti yoga, or devotional practices, as the path for all followers. That is to say, Vaishnavism focuses on self-transcending love and surrender as the principal means of liberation. In addition, karma yoga is advised as a purificatory preparation for the practices of devotion. Sri Ramanuja states that in preparation for meditation, or the contemplative remembrance of the Divine, one should engage in karma yoga.§

Some Vedantic traditions put forth jnana yoga as the path for all. For example, in the Smarta tradition of Adi Shankara, karma yoga is performed as a preliminary sadhana leading one to jnana yoga, which is defined as meditation based on philosophical discrimination. This idea is found in Shankara’s Vivekachudamani: “Work is for the purification of the mind, not for the perception of Reality. The realization of Truth is caused by discrimination, not in the least by ten millions of acts.”§

A fourth approach is that the practice of karma yoga, bhakti yoga and raja yoga constitute a prerequisite for taking up jnana yoga, or experiencing unity with God, enlightenment. Swami Ramakrishnananda of the Vishwa Dharma Mandalam in New York City wrote: “Before delving into jnana yoga, it is important that a disciple grows and develops in service, or karma yoga, in devotion to God, or bhakti yoga, and in meditation, or raja yoga, because in studying this philosophy without preparation one risks transforming oneself into a ‘lip Vedantist,’ a person who talks about that which he does not truly know.”§

Swami Vishnudevananda of Sivananda Yoga Vedanta Centres propounded a similar idea: “Before practicing jnana yoga, the aspirant needs to have integrated the lessons of the other yogic paths—for without selflessness and love of God, strength of body and mind, the search for Self Realization can become mere idle speculation.”§

Satguru Sivaya Subramuniyaswami saw wisdom in this fourth approach. He stated, “Karma yoga and bhakti yoga are the necessary prelude to the higher philosophies and practices.” In fact, he taught that the yogas (or padas) are cumulative stages. Moreover, none should be abandoned as one advances on the path. About bhakti, he said, “We never outgrow temple worship. It simply becomes more profound and meaningful as we progress through four spiritual levels. In [karma yoga or] the charya pada, the stage of selfless service, we attend the temple because we have to, because it is expected of us. In the kriya pada [bhakti], the stage of worshipful sadhanas, we attend because we want to; our love of God is the motivation. In the yoga pada, we worship God internally, in the sanctum of the heart; yet even the yogi immersed in the superconscious depths of mind has not outgrown the temple. It is there—God’s home on the earth plane—when the yogi returns to normal consciousness. So perfect is the temple worship of those who have traversed the jnana pada that they themselves become worship’s object—living, moving temples.”§

Confused as to which yoga or yogas to choose? Of course if you have a teacher, this is an excellent point of discussion to have with him or her. If you don’t have a teacher, then a conservative approach is to work first on karma yoga and bhakti yoga. These yogas work swiftly with the ego and clear all-important barriers to deeper realization, barriers too many neglect to resolve on the path. The benefits of their practice include a slow purification of the mind, developing of greater humility and selflessness and a growing sense of devotion and certainty that all our actions are steadily moving us closer to God.§

PUBLISHER’S DESK • JULY 2017§

Surrender Is Central to All Yogas

______________________§

It is perhaps a great cosmic irony that to attain our immortal Self we must relinquish our personal self§

______________________§

BY SATGURU BODHINATHA VEYLANSWAMI§

INDIVIDUALS WHO ARE NOT RELIGIOUS MAKE progress toward achieving their goals in life by self-effort. Whatever they accomplish is, from their perspective, solely the result of what they do to achieve it. People who are religious have another factor in their life—the help of divine forces. Even in Buddhism, which does not recognize a Supreme Being, the idea of surrendering to a higher power is present, as followers take refuge in the Buddha, the teachings and the brotherhood. Religious individuals invite blessings into their lives by practicing self-surrender, humble submission or taking refuge in the Divine.§

INDIVIDUALS WHO ARE NOT RELIGIOUS MAKE progress toward achieving their goals in life by self-effort. Whatever they accomplish is, from their perspective, solely the result of what they do to achieve it. People who are religious have another factor in their life—the help of divine forces. Even in Buddhism, which does not recognize a Supreme Being, the idea of surrendering to a higher power is present, as followers take refuge in the Buddha, the teachings and the brotherhood. Religious individuals invite blessings into their lives by practicing self-surrender, humble submission or taking refuge in the Divine.§

Before individuals have surrendered to the Divine, their free will is likely an expression of their instinctive nature, focused on accomplishing what they desire, which often entangles them more in the world. If that instinctive willfulness is thwarted or they fail to achieve their goals, the reaction is often frustration and anger. Fear and worry are also commonly experienced. Devotees who have surrendered to Ishvara, God as a person, no longer become angry or live in fear or worry. As my Gurudeva wrote,”When difficult times come, they know it is because they are being unwound from accumulated and congested, difficult karmas or being turned in a new direction altogether. They know that at such a time they have to consciously surrender their free, instinctive willfulness and not fight the divine happenings, but allow the God’s divine will to guide their life.”§

Devotion in Bhakti Yoga§

When looking at self-surrender within Hinduism, it is natural to think first of bhakti yoga. In fact, an alternate term for bhakti yoga is sharanagati yoga, the yoga of self-surrender. This is the practice of devotional disciplines, worship, prayer, chanting and singing with the aim of awakening love in the heart and opening oneself to God’s grace. Such practices are done at the temple, in nature and in the home shrine. Bhakti yoga seeks communion and ever closer rapport with the Divine, nurturing qualities—such as love, selflessness and purity—that make such a profound relationship possible.§

In Hinduism, the soul comes closer and closer to God through these practices. In Vaishnavism, the devotee is seen as progressing through five levels of relationship with God: neutrality, servitude, friendship, parental affections, and belovedness. Saivism has a similar paradigm for the relationships between jiva and Siva. The final stage is called prapatti or atmanivedana, defined as unconditional submission to God.§

My guru, Sivaya Subramuniyaswami, shared: “You might ask how you can love something you cannot see. Yet, the Gods can be and are seen by mature souls through an inner perception they have awakened. This psychic awakening is the first initiation into religion. Every Hindu devotee can sense the Gods, even if he cannot yet inwardly see them. This is possible through the subtle feeling nature. He can feel the presence of the Gods within the temple, and he can indirectly see their influence in his life.”§

Devotion in Karma Yoga§

While most commentators agree that surrender is central to bhakti yoga, few acknowledge its importance in karma and raja yoga. Karma yoga is the path of service and sacred action. In its most profound sense, it is performing all actions in a spiritual manner, as a conscious offering to the Divine. This can be conceived of as worshiping God by serving all beings as His living manifestations. The fruit of all action is surrendered as service to the Lord, a concept known as Ishwara arpana buddhi in Sanskrit.§

Normally karma yoga is done at a temple or ashram, but it is wise to extend service as widely in your life as you can, such as helping others in your workplace, performing beyond what is expected, willingly and without complaint. Performing menial tasks in the home, temple or ashram is an effective way to restrain pride and nurture humility. Practically speaking, this can include washing dishes, laundering clothes, caring for the kitchen and bathrooms, working in the gardens, washing the windows and sweeping the paths—all without seeking or expecting praise.§

Performing our work with the aim of reaching God naturally leads to the perspective that each task is an offering to the Lord. Every act, from the grandest to the lowliest, becomes a sacred rite. Work is worship. The whole of life is sanctified, and the conflict between secular and spiritual ceases to exist.§

Karma yoga can ultimately lead to the realization that the universe is all the action of God. This insight gives the perspective of not merely renouncing the fruit of action but also surrendering the sense of being the doer. My Gurudeva shares an insight on this: “Having the Self as a point of reference and not the material things, with the life force constantly flooding through these nerve currents, you are actually seeing what you are doing as part of the cosmic dance of Siva [Ishvara], as the energy of Siva flows in and through you.” Paramaguru Yogaswami put it simply in one of his four great sayings: “Siva is doing it all.”§

Devotion in Raja Yoga§

Surrender has a seldom-recognized place in raja yoga as well, as Patanjali noted in his Yoga Sutras. Raja yoga begins with ethical restraints and religious observances followed by ever-deepening stages of concentration, meditation and contemplation. Samadhi is the goal of yoga, a oneness between the meditator and the object of meditation, and surrendering to God, to Ishvara, is the key to attaining it. Patanjali speaks of it as Ishvara pranidhana, the fifth essential observance (niyama), the surrender of our limited self-identity to the infinite perfection of Ishvara, the source of the yoga teachings. This surrender is the acceptance of God’s perfection and our desire to be influenced by that as we progress on the yoga path. We seek divine blessings, wisdom and ultimately union, samadhi, through the grace of the adi (first) guru of yoga.§

Before developing Ishvara pranidhana, progress in yoga is self-centered. We think, “I am making yogic progress through my striving and dispassion.” Ishvara pranidhana supplements such effort with reliance on Ishvara to bestow the ultimate grace called samadhi.§

Swami Hariharananda Aranya interprets Patanjali’s thinking: “Through contemplation on God as on a liberated being, the mind in the normal course also becomes calm and thereby concentrated. From knowledge derived through such concentration, the spiritual needs of a yogin are met.”§

Let us compare this to taking a test in school. If you were to simply study and take the test, you would get a B+. However, by also sincerely seeking God’s blessings, you do better and earn an A. In all complex fields, an individual can only go so far on his or her own. To truly master any discipline, a qualified teacher or coach is needed. What better teacher for raja yoga than its progenitor and first guru—Ishvara? Taking Ishvara as your teacher is done through the practice of Ishvara pranidhana.§

My guru gives an insightful description of how the advanced meditator practices self-surrender, or giving up, while experiencing God’s absolute state (Si) and God’s all-pervading consciousness (Va): “While in a dual state of assuming some personal identity, he states, ‘Siva’s will be done,’ as his new and most refined sadhana of giving up the last of personal worldliness to the perfect timing of the infinite conglomerate of force and non-force within him. This he says as a mantra unto himself when he sees and hears in the external world. But when eyes and ears are closed, through the transmuted power of his will he merges into the samadhi of Va and Si and Si and Va, experiencing Reality as himself and himself as Reality.”§

As we have shown, surrender is present in three major yogas: bhakti, karma and raja. Its role is central to realizing the deepest attainments of all three disciplines. It is perhaps an irony that to attain our immortal Self we must relinquish our personal self.§

PUBLISHER’S DESK • APRIL 2010§

Can Everyone Benefit from Yoga?

______________________§

While openly available, yoga is rooted in Hindu scripture, teaches Hindu practices and leads to oneness with God. Practice with caution!§

______________________§

BY SATGURU BODHINATHA VEYLANSWAMI§

ONE OF THE EVENTS WE WERE PRIVILEGED to participate in at the Parliament of the World’s Religions in Melbourne was an interreligious panel entitled “Practicing Yoga: Covert Conversion to Hinduism or the Key to Mind-Body Wellness for All?” At this largest-ever interfaith gathering, many panels, including this one, focused on the interface of cultures and religions. With yoga becoming so popular in the world, it was a natural candidate for reflection, and the results were, as you will see, fascinating. The Parliament defined the issue and points of discussion thusly:§

ONE OF THE EVENTS WE WERE PRIVILEGED to participate in at the Parliament of the World’s Religions in Melbourne was an interreligious panel entitled “Practicing Yoga: Covert Conversion to Hinduism or the Key to Mind-Body Wellness for All?” At this largest-ever interfaith gathering, many panels, including this one, focused on the interface of cultures and religions. With yoga becoming so popular in the world, it was a natural candidate for reflection, and the results were, as you will see, fascinating. The Parliament defined the issue and points of discussion thusly:§

“The science of yoga has grown enormously on the global stage in the last few decades due to widespread recognition of its physical and mental health benefits. Hinduism teaches that yoga is comprised of eight steps, of which the popularly practiced postures are an integral part. Although yoga’s origins are Hindu, its practitioners come from virtually all faiths. The United States alone has about 20 million practitioners, with hundreds of millions worldwide. However, the Hindu roots of yoga and the use of Hindu chants, such as the sacred syllable ‘Om,’ appear to have created apprehensions that the practice of yoga leads to de facto conversion to Hinduism. Yet, as a pluralistic, non-exclusivist and non-proselytizing religion, Hinduism teaches that one need not become a Hindu or repudiate one’s own faith to practice yoga and reap its benefits. How founded is the fear of conversion? Is the practice of yoga inconsistent with the tenets of other religions? Can interfaith dialogue help individuals, irrespective of faith, reap the immense benefits that follow from the practice of yoga? The aim of this program is to foster understanding among faith traditions and to create a sustainable basis for the practice of yoga by all.”§

Rev. Ellen Grace O’Brian, Spiritual Director of the Center for Spiritual Enlightenment and a minister in the kriya yoga tradition, moderated the panel discussion. Five panelists presented diverse viewpoints. Dr. Amir Farid Isahak, a practicing Malaysian Sufi, said that, in his interpretation, yoga can be practiced by Sufis without compromising their religion, provided they are careful about which practices they choose and as long as they focus on a goal of achieving proximity to God, but not unity. Professor Christopher Key Chapple shared information on the philosophical goals of yoga as expounded in Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras. He also spoke of the presence of yoga in Jainism and Buddhism, to demonstrate that long ago yoga moved beyond the boundaries of Hinduism.§

Leigh Blashki of the Australian Institute of Yoga stressed that yoga practice should be not divorced from the spiritual disciplines that are its core. Suhag Shukla, a Hindu who grew up in the US and is now a board member of the Hindu American Foundation, was adamant that yoga and its path of meditation are vital Hindu practices, integral to the religion. My presentation noted that today most popular yoga schools present yoga as a path of unitive mysticism, a meditative regimen that ultimately leads to experiencing the soul’s oneness with God. Here is my summary of the issue.§

Yoga: Unitive Mysticism§

The term yoga refers to a wide variety of Hindu practices. Therefore, it is always helpful when discussing yoga to modify the word with a second term to clarify what particular kind of yoga is being discussed. The yoga that is the subject of this panel is commonly referred to as ashtanga yoga. Ashta means eight, and anga means limb. The idea is that this system of yoga comprises eight progressive practices. Sage Patanjali is credited with being the first person to present the ancient tradition of yoga in a systematic way. He did this in his Yoga Sutras, a famous literary work thought to date back as far as 200 bce. For simplicity, when I use the word yoga in this presentation, I am referring to ashtanga yoga.§

Vamadeva Shastri, a respected author on yoga, astrology and ayurveda, rightly states that the meditative side of yoga is little known: “Yoga today is most known for its asana (yogic posture) tradition—the most popular, visible and outward form of the system. Buddhism, by comparison, is known as a tradition of meditation, as in the more popular forms of Buddhist meditation like Zen and Vipassana. Many people who have studied yoga in the West look to Buddhist teachings for meditation practices, not realizing that there are yogic and Vedantic forms of meditation which are traditionally not only part of the yogic system but its core teaching! In the Yoga Sutras, only three sutras out of two hundred deal with asana. The great majority deal with meditation, its theory and results.”§

To understand yoga’s meditative aspect, it is helpful to look briefly at each of the eight limbs or categories of practice. The first limb is yama, the ethical restraints, of which the most important is ahimsa, noninjuriousness. The second limb is niyama, specific religious observances, including puja in one’s home shrine and repeating mantras. The third limb is asana, the yogic postures that are so widely practiced as a regimen called hatha yoga. The remaining five limbs are all related to meditation: pranayama, breath control; pratyahara, sense withdrawal; dharana, concentration; dhyana, meditation; and samadhi, enstasy, or oneness with God.§

Sometimes it is said that the roots of yoga are Hindu. To develop this botanical metaphor more fully, I would affirm that, yes, the roots of yoga, its scriptural origins, are Hindu. But the stem of yoga, its practice, is also Hindu. The flower of yoga, mystical union, is also Hindu. In other words, yoga, in its full glory, is a vital part of modern Hinduism.§

HINDUISM TODAY§

Yoga panelists: (left to right) Rev Ellen Grace O’Brian of the Center for Spiritual Enlightenment in San Jose, California; Suhag Shukla, Esq., legal counsel for the Hindu American Foundation; Professor Christopher Key Chapple of Loyola-Marymount University; Leigh Blashki, director of the Australian Institute of Yoga; Satguru Bodhinatha Veylanswami, publisher of HINDUISM TODAY magazine in Hawaii; Dr. Amir Farid Isahak, a Qigong and Reiki Master of Malaysia.§

Yoga is practiced on a large scale in Hindu communities around the globe. The fact that yoga is also pursued by many non-Hindus does not negate it as a Hindu practice. Let’s draw a parallel to Vipassana, the popular Buddhist meditative system. The practice of Vipassana by those who are not Buddhist does not lessen the fact that Vipassana is a Buddhist practice, not merely a practice that has its origins in Buddhism.§

Can non-Hindus Benefit from yoga? Clearly, more and more people today, including adherents of other religions, are convinced that this is possible. Take, for example, the title of an opinion piece in an August 2009 edition of Newsweek: “We’re All Hindus Now.” The article quotes the view of Stephen Prothero, religion professor at Boston University, on the American propensity for “the divine-deli-cafeteria religion.” He states: “You’re not picking and choosing from different religions because they’re all the same. It isn’t about orthodoxy. It’s about whatever works. If going to yoga works, great—and if going to Catholic mass works, great. And if going to Catholic mass plus the yoga plus the Buddhist retreat works, that’s great, too.”§

However, it is equally true that the leaders of some religions have spoken out strongly against the practice of yoga by their followers. For example, the Vatican has issued a number of warnings to Catholics about yoga over the years. In 1989 it warned that practices like Zen and yoga can “degenerate into a cult of the body” that debases Christian prayer. Further, the Church leaders cautioned, “The love of God, the sole object of Christian contemplation, is a reality which cannot be ‘mastered’ by any method or technique.”§

In 2008 the leading Islamic council in Malaysia issued an edict prohibiting the country’s Muslims from indulging in the practice of yoga, fearing its Hindu roots could corrupt them. The council’s chairman, Abdul Shukor Husim, explained the decision: “We are of the view that yoga, which originates in Hinduism, combines a physical exercise, religious elements, chanting and worshiping for the purpose of achieving inner peace and ultimately to be at one with God. For us, yoga destroys a Muslim’s faith. There are other ways to get exercise. You can go cycling, swimming.”§

In a search on the web, another informative example turned up. In 2001 the Reverend Richard Farr, vicar of St Mary’s church in Henham, England, made a decision that became the talk of the Essex village and beyond: he banned a 16-strong group of yoga enthusiasts from taking lessons in his church hall. Yoga is, he said, an un-Christian practice: “I accept that for some people it is simply an exercise. But it is also often a gateway into other spiritualities, including Eastern mysticism.”§

The Christian and Muslim leaders we cite as examples stated no concerns that the practice of yoga might result in conversion to Hinduism. However, all three expressed the concern that yoga practice is in conflict with the tenets of their religions. As Abdul Husim expressed it, “Yoga destroys a Muslim’s faith.”§

This predictably raises the question, “What are the tenets of yoga?” We find an authoritative answer in the teachings of B.K.S. Iyengar, one of the most renowned modern teachers of yoga. His system, known as Iyengar Yoga, is widely popular, as evidenced by the thousands of teachers listed on his website. There, in answer to his most frequently asked question, “What is yoga?” he states, “Yoga is one of the six systems of Indian philosophy. The word yoga originates from the Sanskrit root yuj, which means ‘union.’ On the spiritual plane, it means union of the Individual Self with the Universal Self. Sage Patanjali penned down this subject in his treatise known as Yoga Sutras.”§

Another popular yoga teacher, Bikram Choudhury, founder of Bikram Yoga, defines it in a similar way on his website, stating that yoga means union of the Individual Soul (Atman) with the Universal Soul (Brahman). He states, “Atman and Brahman are Hindu ideological terms that are used as a reference for the mind, whereas there truly is only Oneness.” §

Clearly, it is not just its specific practices, such as chanting the mantra “Om,” that make yoga Hindu. It is the philosophy itself. The fact that the goal of yoga philosophy is mystical experience—or, more precisely, a mystical experience of the oneness of the soul with God—is the most central attribute that makes it inherently Hindu. §

Conclusion: It is naive to take yoga as a physical system of exercise devoid of its philosophical, spiritual and cultural underpinnings. This profound spiritual discipline is ineluctably rooted in Hindu scripture. It is a path of religious practice on all levels, and its goal is enlightenment, Self Realization. It may not be an advisable practice for followers of religions in which unitive mysticism is unacceptable, as stated by the religious leaders of such faiths. Those who are affiliated with liberal religions and those with no formal religious ties can definitely benefit from the practice of yoga, physically, emotionally, mentally and spiritually. However, a caution to all who follow the path of yoga: be prepared to become gradually more and more aware of the unity of all that exists!§

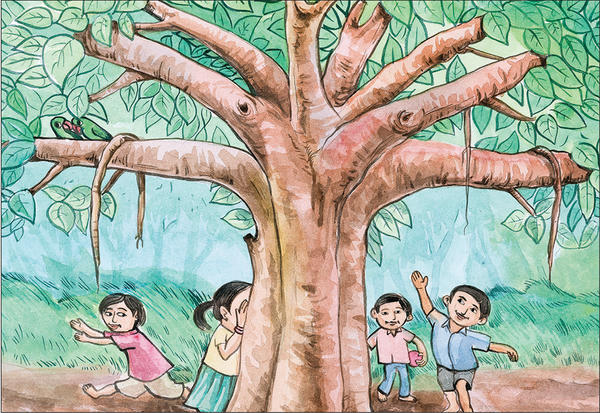

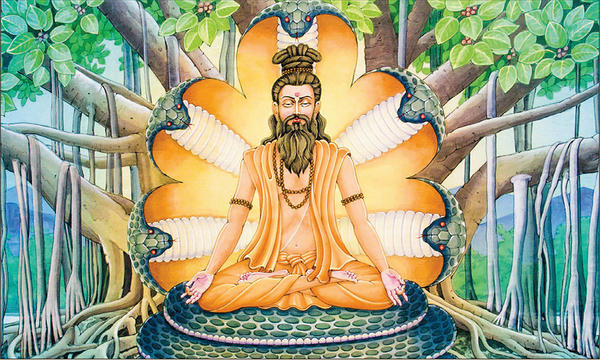

RAJEEV NT§

Yoga has eight limbs: (Below) To depict raja yoga, artist Rajeev NT has chosen a spritely theme. Four children have found a banyan tree in the forest, with eight branches representing the eight limbs of ashtanga yoga. (Right) Yogi Patanjali meditates in padmasana beneath the holy banyan tree (Ficus bengalensis), with its roots woven deeply into the earth. Its eight limbs, representing the eight stages of yoga, reach for the sky. The illustration reminds us that a yogi must be grounded to soar within. A five-headed serpent, symbolizing the kundalini power, surrounds him.§

Yoga Is One of the Six Classical Hindu Philosophies

PIETER WELTEVREDE§

Among the most compelling facts supporting the deep association of yoga with Hinduism is its place as one of the six foundational philosophical systems that have been studied and debated for nearly a millennium. Here is a thumbnail sketch of those schools, known in Sanskrit as the Shad Darshanas (“six perspectives”). There are hundreds of Hindu darshanas, of which six have been distinguished: Nyaya, Vaisheshika, Sankhya, Yoga, Mimamsa and Vedanta. Each was tersely formulated in sutra form by its founder or first well-known exponent and elaborated extensively by other writers. These systems are varied attempts at describing Truth and the path to it. Elements of each form part of the Hindu mosaic today.§

Nyaya: “System, rule; logic.” A system of logical realism, founded sometime around 300bce by Gautama, known for its systems of logic and epistemology and concerned with the means of acquiring right knowledge. Its tools of enquiry and rules for argumentation were adopted by all schools of Hinduism.§

Vaisheshika: “Differentiation,” from vishesha, “differences.” A philosophy founded by Kanada (ca 300bce) teaching that liberation is to be attained through understanding the nature of existence, which is classified in nine basic realities (dravyas): earth, water, light, air, ether, time, space, soul and mind. Nyaya and Vaisheshika are viewed as a complementary pair, with Nyaya emphasizing logic, and Vaisheshika analyzing the nature of the world.§

Sankhya: “Enumeration, reckoning.” A philosophy founded by sage Kapila (ca 500bce), author of the Sankhya Sutras. Sankhya is primarily concerned with “categories of existence,” tattvas, which it understands as 25 in number. The first two are the unmanifest Purusha and the manifest primal nature, Prakriti—this male-female polarity is viewed as the fundament of all existence. Prakriti, out of which all things evolve, is the unity of the three gunas: sattva, rajas and tamas. The Sankhya and Yoga schools are considered an inseparable pair. Their principles permeate all of Hinduism.§

Yoga: “Yoking; joining.” The ancient tradition of philosophy and practice codified by Patanjali (ca 200bce) in the Yoga Sutras. It is also known as raja yoga, “king of yogas,” or ashtanga yoga, “eight-limbed yoga.” Its object is to achieve, at will, the cessation of all fluctuations of consciousness, and the attainment of Self Realization. Yoga is wholly dedicated to putting the high philosophy of Hinduism into practice, to achieve personal transformation through transcendental experience, samadhi.§

Mimamsa: “Inquiry” (or Purva, “early,” Mimamsa). Founded by Jaimini (ca 200bce), author of the Mimamsa Sutras, who taught that the correct performance of Vedic rites is the means to salvation. §

Vedanta: “End (or culmination) of the Vedas,” sometimes termed Uttara (“later”) Mimamsa. For Vedanta (the “end,” anta, of the Vedas), the main basis is the Upanishads and Aranyakas, rather than the hymns and ritual portions of the Vedas. The teaching of Vedanta is that there is one Absolute Reality, Brahman. Man is one with Brahman, and the object of life is to realize that truth through right knowledge, intuition and personal experience. The Vedanta Sutras (or Brahma Sutras) were composed by Rishi Badarayana (ca 400bce).§

PUBLISHER’S DESK • APRIL 2006§

The World Is an Ashram

______________________§

Life is demanding and you have no time for spiritual pursuits? Everyday happenings offer abundant opportunities to evolve.§

______________________§

BY SATGURU BODHINATHA VEYLANSWAMI§

IN HINDUISM WE ARE FORTUNATE TO HAVE MANY God-Realized souls to guide us along the spiritual path. Their teachings are so profound and powerful that they penetrate our normal consciousness and give us new insights into how to live to maximize our spiritual progress.§

IN HINDUISM WE ARE FORTUNATE TO HAVE MANY God-Realized souls to guide us along the spiritual path. Their teachings are so profound and powerful that they penetrate our normal consciousness and give us new insights into how to live to maximize our spiritual progress.§

Our paramaguru, Yogaswami, of Jaffna, Sri Lanka, gave us one such gem when he said, “The world is an ashram, a training ground for the achievement of moksha, liberation.”§

Yogaswami’s statement has a parallel in William Shakespeare’s play “As You Like It.”§

All the world’s a stage,§

And all the men and women merely players:§

They have their exits and their entrances;§

And one man in his time plays many parts,§

His acts being seven ages.§

Here is a paraphrase of Shakespeare’s lines, adapted to reflect Yogaswami’s spiritual meaning:§

All the world’s an ashram,§

And all the men and women are divine souls;§

They are spiritually maturing through earthly experiences,§

And one soul in its time takes many births,§

And thus evolves into oneness with God.§

Let’s look more closely at what it means to say that all the world’s an ashram. An ashram, of course, is the residence and teaching center of a swami or spiritual preceptor. It is a place we go to learn about our religion and make spiritual progress. When we go out the door of our home to go to work, school or elsewhere, do we have in mind that we are going to an ashram, that our actions during the day in the office, factory, hospital, classroom or elsewhere will help us evolve spiritually and bring us closer to moksha? Probably not. When we come home and reflect back on the day, do we feel we made spiritual progress while out of the home? Probably not. Why is this? It is because we have not been trained to look at life in this way. We think of the ashram as a place of spiritual advancement, and we regard the world as a place of mundane tasks and distractions from our spiritual work. The common idea is that what we do in the ashram, the home shrine or the temple is what brings us spiritual progress, and what we do at the office or in the classroom has nothing to do with our spiritual life.§

This common perspective is not the viewpoint of great souls such as Yogaswami. Such souls know that much spiritual progress can be made during our time in the world if we hold the right perspective. I call this approach “spiritualizing daily life.” Let’s bring this concept down to Earth by dividing the occasions for spiritual progress when out in the world into two categories: facing life’s challenges and finding opportunities to serve.§

First, let’s look at facing life’s challenges. Life is going to come to you whether you want it to or not. Joyful, easy times, difficult times, happy days and sad—it is all coming. It is all there, in your karma. It can’t help but come. So you don’t have to go looking for it. You don’t have to go try and do something different. You can’t avoid it. You can’t hide from it.§

Life’s challenges will come to us. What is going to happen is going to happen. But where the focus should be, for those on the spiritual path, is on how we respond to these challenges. Why? Because that is where we have a choice. For example, a small infant keeps us awake all night by crying. How do we respond to it? Does it upset us? Do we complain? Or, do we just accept it and respond back with lots of love? In every experience of life we have control over our response. It can be impulsive or thoughtful. It’s our choice.§

When accused of something that we didn’t do, how do we respond? When we face challenges at work—say our boss is unfair with us, yells at us—what is our reaction? We want to yell back, but cannot. So, do we go home and yell at the spouse? In all such cases, we have choices. It is not the challenges that come, but how we face those challenges that makes the difference. We can react emotionally without thinking about spiritual principles. We can get angry or despondent. We can worry a lot and become irritable.§

Or we can decide to control any emotional reactions that we might have. We can choose to live without anger. We can choose to cultivate patience. We can choose to be kinder to other people, to be more generous. That is what makes us spiritually stronger. As we curb our instinctive nature, our soul nature shines forth. In other words, if we get angry now and then, let us try and eliminate anger altogether. If we get impatient with people who seem to explain things at great lengths when they could be explained in a short way, let’s learn how not to get impatient. Let us learn how to accept that verbosity is their nature.§

Here is the list of six common challenges we face in life that provide us with good opportunities for spiritual progress if we respond in a wise manner with self-control.§

Opportunities are everywhere: Our daily work, whatever it may be, brings opportunities to learn patience, cooperation, poise and a genuine appreciation for others who share our life and career.§

First Challenge: Mistreatment by Others. Life provides us a steady stream of experiences in which we are mistreated by others. Rather than retaliate or hold resentment, we can forgive and respond with kindness.§

Second Challenge: Our Own Mistakes. When we make a major error, we have a choice to wallow in self-doubt and self-deprecation or to figure out how to not repeat the mistake.§

Third Challenge: Difficult Projects. When faced with tasks that stretch our abilities, we can do the minimum just to get by or be inspired to do our best by looking at them as opportunities to improve our concentration, willpower and steadfastness, all of which will enhance our meditation abilities and inner striving.§

Fourth Challenge: Disturbed Emotions. When we get upset by life’s experiences, we have a choice to suffer the emotional upheaval or to strive to pull ourselves out of it as quickly as possible.§

Fifth Challenge: Interpersonal Conflicts. When serious disagreements, quarrels or arguments occur, we have a choice to hold a grudge and perhaps even shun the person or to resolve the matter and keep the relationship harmonious.§

Sixth Challenge: Gossip and Backbiting. When those around us indulge in gossip, rumors, backbiting and intrigue, we have a choice to join in or to not participate and even, among those close to us, make it clear that we do not approve.§

The second category of occasions for spiritual progress when out in the world is what I call finding opportunities to serve. Here is an introduction to this concept from Gurudeva’s Living with Siva which beautifully illustrates the idea of spiritualizing daily life through service.§

“Go out into the world this week and let your light shine through your kind thoughts, but let each thought manifest itself in a physical deed of doing something for someone else. Lift their burdens just a little bit and, unknowingly perhaps, you may lift something that is burdening your mind. You erase and wipe clean the mirror of your own mind through helping another. We call this karma yoga, the deep practice of unwinding, through service, the selfish, self-centered, egotistical vasanas [subconscious inclinations] of the lower nature that have been generated for many, many lives and which bind the soul in darkness. Through service and kindness, you can unwind the subconscious mind and gain a clear understanding of all laws of life. Your soul will shine forth. You will be that peace. You will radiate that inner happiness and be truly secure, simply by practicing being kind in thought, word and deed.”§

There are many opportunities to help others at home, work, school, in the neighborhood and community. We have developed a list of six simple practices. Let me briefly introduce them.§

First Opportunity: Seeing God in Those We Greet. When greeting someone, we strive to look deeply enough into them to see God, to see them as a divine being evolving through experience into oneness with God. Our attitude is then naturally helpful and benevolent.§

Second Opportunity: Volunteering. There are many opportunities each day to step forward and offer to help in ways that are beyond what is required of us. An attitude of humble service diminishes the ego and strengthens our spiritual identity. One important spiritual attitude to hold is to be willing to help when called upon, to not resist or refuse—to be as open to helping others as you are in doing things for yourself.§

Third Opportunity: Expressing Appreciation. We can uplift and encourage others by sincerely expressing how grateful we are for their help, friendship and importance in our life.§

Fourth Opportunity: Helping Newcomers. In our modern world, people move around a great deal. Thus there is a steady flow of newcomers at work, at school, in our neighborhood and at our temple. Stepping forward to welcome and help orient them to their new environment is an excellent way to be of service.§

Fifth Opportunity: Offering Hospitality. Everyone can find creative ways to be hospitable in the home, at school and even at work.§

Sixth Opportunity: Making Encouraging and Complimentary Remarks. Make a point to say something encouraging and complimentary to everyone you meet. Their day will be brighter because of it, and so will yours.§

In conclusion, having a great day needs to mean more than getting a bonus at work or an A on a school test. It should include the spiritual progress you made that day through effectively facing life’s challenges and the ways in which you helped and uplifted others. Our list of twelve practices is a good beginning, but hopefully you will keep expanding it as additional insights come from your striving to maximize the spiritual progress you can make from the experiences and opportunities each day brings. Also, parents can teach children to consciously strive for spiritual progress each day at school by facing life’s challenges and finding opportunities to serve.§

PUBLISHER’S DESK • APRIL 2008§

Four Ways We View the World

______________________§

Meditative, philosophic, scientific and supramundane are dynamic perspectives we can employ every day§

______________________§

BY SATGURU BODHINATHA VEYLANSWAMI§

IN HIS MYSTICAL LANGUAGE OF MEDITATION, CALLED Shum (pronounced shoom), my Gurudeva, Sivaya Subramuniyaswami, brought forth a unique insight: four perspectives through which people look at the world. While this is a bit more esoteric and abstract than most Publisher’s Desk subjects, I think you will find it interesting and useful. Let me introduce you to these varied ways you can view the cosmos.§

IN HIS MYSTICAL LANGUAGE OF MEDITATION, CALLED Shum (pronounced shoom), my Gurudeva, Sivaya Subramuniyaswami, brought forth a unique insight: four perspectives through which people look at the world. While this is a bit more esoteric and abstract than most Publisher’s Desk subjects, I think you will find it interesting and useful. Let me introduce you to these varied ways you can view the cosmos.§

1. Shumif: The first perspective is shumif (shoomeef), simply defined as awareness flowing through the mind, the mind itself being unmoved. This is the perspective we hold in meditation. Awareness, our identity, is a traveler, able to move freely about, investigating various areas of the mind, like a visitor to the various regions of the United States. If he wants to experience San Francisco, he travels there. If he wants to see Denver, which is much different from San Francisco, he travels there. He is moving, and the cities are stationary. Similarly, in the shumif perspective your awareness is the traveler in the mind, and the various parts of the mind—emotion, thought, intuition—are stationary. One of the goals of meditation is to increase your ability to move freely and at will.§

In our ordinary way of thinking and speaking, if we are upset we complain, “I’m upset. That’s the way I am. After a while, I probably will be calm again.” But from the shumif perspective we say, “My awareness has ended up in the area of the mind that is always upset. Do I want to be here or not? No, this is ruining my day!” So, we affirm, “OK, I don’t want to be here,” and we apply certain tools for moving to an area of mind that is more wholesome and pleasant. But first we have to have the concept that we can move—that it is within our power to change where we are in the mind. Similarly, if a visitor to the Mojave Desert decides, “It’s too hot here for me,” he knows he can simply move on.§

Four modes of the mind: Meditative (awareness moving through the mind), scientific (awareness is stationary, observing movement in nature), philosophic (study and understanding), supramundane (cognizance of inner and outer worlds beyond the mundane, such as the world of the Gods)§

2. Simnif: The second perspective is called simnif (simneef). From this vantage point, the mind is moving, and the intelligence of the person observing remains stationary. Looking through a microscope at a drop of water, what do we see? Movement. You see many different things in motion. You are the stationary observer, and what you see is moving. You are stationary when looking into an ocean and seeing schools of fish moving here and there. That is the perspective of science or any field of knowledge based on the observation of matter. These first two cosmic points of view, shumif and simnif, are exactly opposite.§

3. Mulif: The third perspective, mulif (mooleef), is philosophical, metaphysical and psychological. Gurudeva gave the following description: “Mulif is the way of words, the way of the scholars of philosophical intellect. It is the perspective of some of the religions of the world. It is the perspective that all realization, all understanding, is worked out within and among people and their minds. In this perspective, one is unaware of the Gods, the three perfections of Lord Siva, the existence of beings on other planets, spacecraft. It is more of a subjective, intellectual perspective as to the nature of the universe, God and man. Realization is often attained in mulif through simply understanding deep philosophical concepts. This would be an intellectual realization, not a spiritual one.”§

For example, we may talk about the absolute perfection of God—Parasiva or Parabrahman—as timeless, causeless and spaceless. To know and understand such a truth is good philosophy, but it is not the same as experiencing it. To make that distinction is important. Experiencing it is in the shumif perspective. Describing it is in the mulif perspective. Mulif is necessary, philosophy is necessary, because we have to understand intellectually what it is we are trying to experience; but we don’t want to accept the concept as the experience itself. As Sage Yogaswami once admonished a scholarly disciple, “It is not in books, you fool.”§

4. Dimfi: The fourth, dimfi (deemfee), is the perspective of space or worlds—inner worlds and outer worlds. Our most common use of dimfi in Hindu practice is in our worship of the Deities in the temple. The Deities abide in the inner worlds. This is the vantage point of theism. The Deity is separate from us; the Deity is greater than we are. Through prayer, we draw forth the blessings of the Deity. That is the spirit of temple worship. It is, as Gurudeva explains, “the focus or consciousness that acknowledges, understands and communicates with God and Gods, beings on the astral plane, people from other planets. It is here that all psychic phenomena take place and the mind is open to all kinds of possibilities, of the extraterrestrial, out-of-body experiences, etc. Here reincarnation is understood. Mulif and dimfi are exactly opposite.”§

These four major perspectives create what Gurudeva once called one’s “inner mind styling.” Many people live in just one of them their entire life without realizing it. An experienced meditator, however, can learn to consciously live in two, three or more at the same time. How can we relate these viewpoints to everyday life? Let’s take a common problem—depression—and look at how a Hindu devotee might alleviate it from each of these approaches.§

The simnif, or scientific, perspective is often favored. We solve our sorrows by taking an anti-depressant drug, such as Prozac, to chemically alter our mood. The chemistry of medical science is our way out. It sounds dubious, but that’s what’s going on in the world. Even young children are being put on these medications. In severe cases, drugs may be necessary, but they do have side effects and don’t come without an overhead, shall we say. However, simnif can be used positively for changing one’s state of mind: applying the wisdom of ayurveda, exercising more, performing hatha yoga and improving one’s diet.§

Discussing the depression with a friend, counselor or psychologist is the solution from the mulif, or psychological, perspective. The counselor tries to talk someone into feeling better about themselves, talk them out of the problem, by gaining a new understanding. A professional counselor might advise, “You are a wonderful, divine being! You are perfect. Every experience is a good experience if you learn something from it.”§

Going to the temple for relief is the dimfi, inner-plane, approach. It’s not commonly prescribed for depression, but it should be—going to the temple and placing your problems at the Feet of the Deity. We bring offerings, talk to the Deity about our unhappiness and go through a deep, inner process, just as if we were talking to a person in this physical world. But we receive blessings from the Deity, if we open ourselves in the right way. A force is awakened which you don’t get from a person—a blast of divine energy that helps remove the problem. Sometimes, if it works out well, you may go away not even remembering what the problem was. That’s a sign of success.§

Alleviating depression through meditation is the shumif, or meditative, approach, moving awareness into a happier state of mind, then looking back and cognizing the karmas involved. This is the most advanced method, because the hardest time to meditate is when we’re upset, sad or bothered. Still, it can be done.§

Oftentimes you can use more than one perspective to help someone out of a slump. Start with mulif to improve the person’s mood, reminding him he is a divine being. Listen closely and empathize with his situation, while trying to give him an overview. Then you can move on to dimfi. Recommend that he go into the temple or shrine room and talk to Ganesha about it, place the matter at His Feet and beseech the Mighty One to adjust his emotional state. If he is a good meditator, you can suggest that he then sit down and meditate: “Go into the energies in the spine and become positive again. That powerful spiritual energy is right there within you, and you know how to access it.” He may also benefit by getting more fresh air and exercise. In this way, you can use all four perspectives to uplift him.§

We try to avoid the all-too-frequent simnif approach of prescribing drugs for depression. A devotee whose spouse recently passed away at a young age told me, “I’ve been advised by a doctor that I’m depressed because of my grief and should take some drugs.” My goodness! Drugs have become a panacea, but grieving is a natural process common to all cultures, because it takes time, often a year or more, to recover from the shock. Rather than confusing grief with depression and taking a drug to make it go away, the better approach is to follow the wisdom of ayurveda, talk about the problem to gain a proper philosophical perspective, beseech divine beings for blessings and change your consciousness through the use of your will.§

Explore these four ways of looking at the universe. They hold the ability to enrich and broaden your life experiences.§