PUBLISHER’S DESK • OCTOBER 2015§

The Journey to Liberation

______________________§

Though moksha may seem remote, there is wisdom in keeping this ultimate goal in mind as we live our day-to-day life§

______________________§

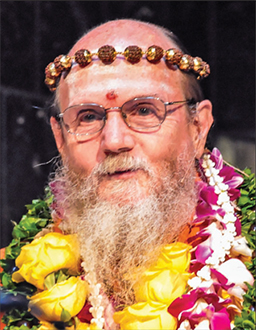

BY SATGURU BODHINATHA VEYLANSWAMI§

“THE RISHIS ASKED THE GODS: ‘WHAT MUST A person do if he wishes to reach the blissful state of union with God? Is there a state that not only confers upon us supreme, unbroken bliss, but also puts an end to pain, sorrow and suffering? Does this process of reincarnation go on forever?’ The Gods explained: ‘No. Each time the soul takes on a new body, it gets closer and closer to becoming perfect. To gain a better birth each time, one must live according to the natural laws that Hinduism proclaims and live out the karma in this life positively and fully while at the same time refraining from creating painful new karmas. After a number of such excellent incarnations, and after God Realization has been attained, the soul body becomes mature enough that it no longer needs to take a physical incarnation. Instead, it continues its evolution on inner planes of consciousness. This release from samsara is called moksha. The soul is said to be freed from the bondage of birth and death.’” With this dramatic passage, my Gurudeva, Satguru Sivaya Subramuniyaswami, explained liberation from rebirth.§

“THE RISHIS ASKED THE GODS: ‘WHAT MUST A person do if he wishes to reach the blissful state of union with God? Is there a state that not only confers upon us supreme, unbroken bliss, but also puts an end to pain, sorrow and suffering? Does this process of reincarnation go on forever?’ The Gods explained: ‘No. Each time the soul takes on a new body, it gets closer and closer to becoming perfect. To gain a better birth each time, one must live according to the natural laws that Hinduism proclaims and live out the karma in this life positively and fully while at the same time refraining from creating painful new karmas. After a number of such excellent incarnations, and after God Realization has been attained, the soul body becomes mature enough that it no longer needs to take a physical incarnation. Instead, it continues its evolution on inner planes of consciousness. This release from samsara is called moksha. The soul is said to be freed from the bondage of birth and death.’” With this dramatic passage, my Gurudeva, Satguru Sivaya Subramuniyaswami, explained liberation from rebirth.§

To attain life’s ultimate purpose, three qualifications must be met: Earthly karma must be resolved; dharma must have been well performed and God must be realized. The Upanishads assure us, “If here one is able to realize Him before the death of the body, he will be liberated from the bondage of the world” (Katha Upanishad 2.3.4).§

Why Even Think About It?§

I have found a sure-fire way to put an audience to sleep within five minutes. It’s to talk at length about moksha. Why is this? The challenges of day-to-day living are a sufficient focus; there is no mental real estate to also think about moksha. After all, there are three other more immediate goals: dharma, wealth and love. Few seem to incorporate moksha into their philosophical framework. Most have only the vaguest concept of what existence after liberation would be like. Besides, why think about something that seems so far off, something to be concerned about in a future life? Knowing that release comes only when the soul is ripe for realization, having matured through many lives, the average devotee concludes that moksha is as remote as Jupiter, strictly the concern of yogis and sadhus.§

The challenge is to make life’s ultimate spiritual attainment relevant to day-to-day family life. In public presentations I refer to moksha as the X-marks-the-spot destination and then describe the journey that leads to it. While the destination may be distant, the journey toward it is already happening, whether we recognize it or not. I ask listeners to visualize a mountain with a winding path leading to the summit, which is blissful experience of God Realization and moksha. In each life we are born near the same point on the path we reached at the end of our last life. Ideally, in each lifetime we move farther up the path toward the mountaintop; we don’t stand still or go backwards. Standing still results from living a materialistic, self-centered life. Going backwards is the price we pay for adharmic deeds, such as serious violence and dishonesty.§

This singular, long-term goal defines the direction of dharma in the well-lived life and provides a north star for all navigating the rough seas of Earthly existence. Most souls have much to do and achieve before striving for it directly, though all hope to attain it ultimately. It is achieved only after a certain level of perfection has been attained, maturity of the soul sufficient to harness the forces of instinct, intellect and emotion. Happily, Hinduism affirms that every person on Earth will eventually reach the unitive state of moksha and be free from rebirth.§

To describe how we can move toward moksha, I use the analogy of dance. I ask listeners, “What is most needed for a youth to become good at Hindu classical dance?” Invariably, most respond with the answer I have in mind: “Practice!” Reading books about dance won’t make you a good dancer. Nor will attending classes without practicing what you have learned. Regular practice is needed to keep the body limber and to master the art. Making strides on the spiritual journey to liberation is the same. To grow and evolve into our divine potential requires regular practice, ideally daily practice. The spiritual advancement we make is directly related to the time and effort we devote to religious practices. Sage Patanjali stresses this in his Yoga Sutras (verse 1.21; 22): “For those who have strong dedication, samadhi is near. Whether one’s practice is mild, medium or intense also makes a difference.”§

Being “on the Path”§

My Gurudeva taught, “When the soul has had enough experience, it naturally seeks to be liberated, to unravel the bonds. That begins the most wonderful process in the world as the seeker steps for the first time onto the spiritual path. Of course, the whole time, through all those births and lives and deaths, the soul was undergoing a spiritual evolution, but unconsciously. Now it seeks to know God consciously. That is the difference. It’s a big difference.” He stressed that seekers who are devout, who are sufficiently awakened to practice yoga, to seek the inner meaning of life have arrived at this crucial stage. While liberation may be lifetimes away, this is indeed the time to cognize the goal and begin molding yourself for it by living in a way that brings advancement and unfoldment of your soul. §

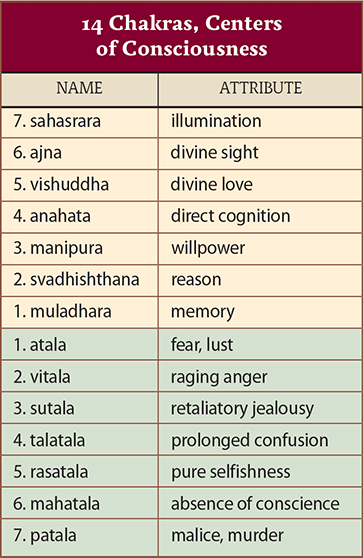

But who has the time in a normal day for a generous period of spiritual practice? Many tell me they have no time at all. Employment, transportation, eating, entertainment, exercise, home duties and spending time with family and friends take up the whole day, every day. As a solution, I recommend shortening the period of sadhana but doing it regularly. For youth I suggest a ten-minute “spiritual workout” of worship, introspection, affirmation and study. (See my full description of the subject in essay 41.) If you are following dharma and performing regular daily sadhana, you can be assured you are moving forward in a significant way in this life on your journey to liberation. As we make progress, we gradually learn to sustain refined states of consciousness, without descending into the lower-chakra realms of fear, anger, jealousy, confusion and malice. After liberation, our consciousness abides fully in the three highest chakras—vishuddha, ajna and sahasrara, force centers of divine love, divine sight and illumination.§

Gurudeva reminded us: “We have taken birth in a physical body to grow and evolve into our divine potential. We are inwardly already one with God. Our religion contains the knowledge of how to realize this oneness and not create unwanted experiences along the way. The peerless path is following the way of our spiritual forefathers, discovering the mystical meaning of the scriptures. The peerless path is commitment, study, discipline, practice and the maturing of yoga into wisdom. In the beginning stages, we suffer until we learn. Learning leads us to service; and selfless service is the beginning of spiritual striving. Service leads us to understanding. Understanding leads us to meditate deeply and without distractions. Finally, meditation leads us to surrender in God. This is the straight and certain path, the San Marga, leading to Self Realization—the inmost purpose of life—and subsequently to moksha, freedom from rebirth.”§

What’s Your Definition?§

The point in evolution at which a soul earns release and the understanding of what happens afterwards is described in many ways. Most schools of Hinduism recognize the condition of jivanmukti, the state of liberation while still embodied. Whether achieved while living or at the point of death, moksha marks an end to one’s earthly sojourn and a graduation to a more refined level of existence. We can get a sense of the range of perspectives from the ancient Brahma Sutra, which cites a number of then-current views: that upon liberation the soul (jiva) attains nondifference from Brahman (IV.4.4); that it gains the attributes of Brahman (IV.4.5); that it exists only as pure consciousness (IV.4.6); that even though it is pure consciousness from the relative standpoint, it can still gain the attributes of Brahman (IV.4.7); that through pure will alone it can gain whatever it wishes (IV.4.8); that it transcends any body or mind (IV.4.10); that it possesses a divine body and mind (IV.4.11); and that it attains all powers except creatorship, which belongs to Ishvara alone (IV.4.17).§

While these views vary, they all describe a state of being and evolution that far transcends normal mortal consciousness. Isn’t that something worth thinking about, something worth striving for? It is the state of great souls such as our paramaguru, Siva Yogaswami, who lives vibrantly in the Sivaloka, inner worlds, showering blessings to devotees on Earth. It is the highest of human achievements, the pinnacle and very purpose of all other experiences in life—the revolutionary transcendence of limited identity in favor of unitive consciousness and all-pervasive love. All the worlds rejoice when an old soul is freed from samsara, the cycle of birth, death and rebirth.§

PUBLISHER’S DESK • JULY 2006§

How Our Soul Matures

______________________§

People the world over are working for spiritual advancement. But just what is the soul and how does it progress and mature?§

______________________§

BY SATGURU BODHINATHA VEYLANSWAMI§

IN HINDU THOUGHT THE CONCEPT OF LIFE AND the soul are synonymous. For example, the Sanskrit word jiva refers to both and contains the meanings of individual soul, living being, life, vitality, energy, spirit and strength. The Tamil word uyir has the same double meaning, of life and soul.§

IN HINDU THOUGHT THE CONCEPT OF LIFE AND the soul are synonymous. For example, the Sanskrit word jiva refers to both and contains the meanings of individual soul, living being, life, vitality, energy, spirit and strength. The Tamil word uyir has the same double meaning, of life and soul.§

The soul, which is so perplexing and seemingly out of reach to many, can be understood simply as life itself. One of the advantages of this simple description is that it makes it easy to experience the soul. How can we do this? Just look into a mirror. Specifically, look deeply into your eyes and see the light and sparkle within them. That life, vitality, willpower and awareness is your soul, your divinity, the real you, that which continues on after the physical body’s passing. Looking into the eyes of another, you can become aware of the life within that person and thereby see the soul and acknowledge his or her divine nature.§

The Tamil word uyirkkuyir takes this concept of divinity one step further. It is translated as “God, who is the Life of life, the Soul of the soul.” A philosophical phrase that conveys the same meaning is “God is the essence of the soul,” implying that if you look deeply enough into the soul, you will experience God.§

How do we know, when seeing the life within ourselves or others, if we are experiencing the individual, evolving soul, or experiencing God as the essence of the soul, the Life of life? Here is one way to make that distinction. When we are perceiving an individual soul or souls, there is a sense that every soul is separate from the others. However, when we perceive God as the Life of life, that sense of separateness is replaced with a sense of oneness. Thus, if you can look at a group of people and be aware of the divine oneness that pervades them all, you would be seeing God in them. This deeper experience is achieved through internalizing our awareness, going deeply inside ourselves through worship or meditation.§

An analogy can be made to japa beads. We can focus on the beads and perceive them as 109 separate beads. We can also focus on the cord on which they are strung and see the oneness that connects all the beads. A popular story about Paramaguru Yogaswami illustrates this point. There were four people gathered to sing devotional songs in his small hut one day. Yogaswami asked, “How many are here?” Someone replied, “Four, swami.” Yogaswami countered, “No. Only one is here.” He saw the unity; they saw the diversity.§

The Hindu idea that God is inside every person as the essence of the soul, which can be experienced today, is quite different from the concept of Western religions that God is up in heaven and cannot be experienced by those living on Earth. They believe they have to die to meet God. Gurudeva often spoke of the immediacy of God’s presence: “God is so close to us. He is closer than our breathing, nearer to us than our hands or feet. Yes, He is the very essence of our soul.”§

Turning now to the goal of life, we know the Hindu perspective is that life’s ultimate purpose is to make spiritual progress. This is also described as evolving, maturing or unfolding spiritually. All of these terms refer to enjoying ever more profound realizations of God—personal experiences that deepen our understandings of life and transform our very nature—culminating in moksha, liberation from rebirth on planet Earth.§

We can usefully distinguish here the Hindu view of the spiritual destination—experience of God and subsequent liberation—and the journey to that destination, which we are speaking of here. By focusing on the journey and the steps in front of us, we progress more surely and swiftly.§

Let’s ask the question, “What, exactly, is it that makes this spiritual progress?” Not the personality. Not the intellect. Not the emotions. It is, of course, the soul. In thinking of spiritual progress, it is helpful to understand the concept of the soul as a human-like, self-effulgent form comprised of the life and light we previously talked about. Technically, there are two terms in Sanskrit for this immortal soul body: anandamaya kosha, “bliss body,” and karana sharira, “causal body.” Just as our physical body matures from an infant into an adult, so too does this self-effulgent body of light mature in resplendence and intelligence, evolving as its consciousness expands, gradually strengthening its inner nerve system, progressing from ignorance of God to intimate communion with God. In Sanskrit, this advancing on the path is called adhyatma prasara, spiritual evolution. It is a process that takes place over many lifetimes, not just one.§

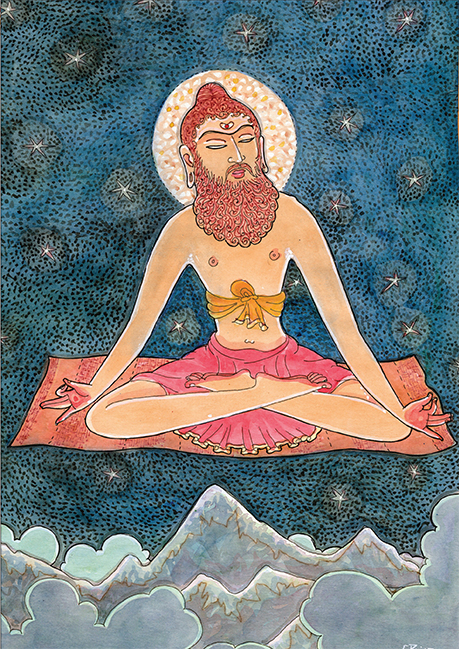

Gurudeva shared, from his own experience, a mystical description of the soul body in Merging with Siva: “One day you will see the being of you, your divine soul body. You will see it inside the physical body. It looks like clean, clear plastic. Around it is a blue light, and the outline of it is whitish yellow. Inside of it is blue-yellowish light, and there are trillions of little nerve currents, or quantums, and light scintillating all through that. This body stands on a lotus flower. Inwardly looking down through your feet, you see you are standing on a big, beautiful lotus flower. This body has a head, it has eyes, and it has infinite intelligence. It is tuned into and feeds from the source of all energy.” Similar descriptions of the soul as a body of light are found in our sacred scriptures and in yogis’ writings.§

Hastening progress: Let’s turn now to the question of what can we do to hasten the unfoldment of our soul. In Hindu thought, there are fourteen great nerve centers in the physical body (sthula sharira), in the astral body (sukshma sharira) and in the body of the soul (karana sharira). These centers are called chakras in Sanskrit, which means “wheels.” Esoterically, spiritual unfoldment relates to the raising of the kundalini force, the serpent power, and the subsequent awakening of these chakras within our subtle bodies. Everyone has all of the chakras, though they usually are content to live in only a few.§

There are six chakras above the muladhara chakra, which is located at the base of the spine. When awareness is flowing through these chakras, consciousness is in the higher nature. There are seven chakras below the muladhara chakra, and when awareness is flowing through them, consciousness is in the lower nature. Most Hindu teachings regarding the chakras focus on the yogi’s awakening, balancing or stimulating the muladhara chakra and the six above. These seven centers of consciousness govern, in order, memory, reason, willpower, direct cognition, divine love, divine sight and illumination/Godliness. However, my guru has a different emphasis. He states that spiritual unfoldment is not a process of awakening the higher chakras, but of closing off the chakras below the muladhara. The seven chakras, or talas, below the spine, down to the feet, are all seats of instinctive consciousness, the origin, respectively, of fear, anger, jealousy, confusion, selfishness, absence of conscience and malice.§

Brahmadvara, the doorway to the Narakaloka located just below the muladhara, has to be sealed off so that it becomes impossible for fears, hatreds, angers and jealousies to arise. Once this begins to happen, the muladhara chakra is stabilized and consciousness slowly and naturally expands into the higher chakras. As the kundalini force of awareness travels along the spine, it enters each of these higher chakras, energizing them and awakening, in turn, each function according to the intensity of spiritual effort.§

This understanding of the centrality of sealing off the lower chakras highlights how important emotional control is to our spiritual progress. Certainly the emotion that is the most important for people on the spiritual path to control is anger. Just possessing the knowledge that anger prevents us from experiencing the higher chakras increases our motivation to live a life that is totally free from this devastating force. Anger comes in many forms, ranging from frustration and resentment to uncontrollable rage. In its simplest shade, it is an instinctive, emotional protest to happenings at a particular moment. “Things are just not right!” anger shrieks. The source of peace and contentment is the opposite sentiment—a wholesome, intelligent acceptance of life’s conditions, based on the understanding that God has given us a perfect universe in which to grow and learn, and each challenge or seeming imperfection we encounter is an opportunity for spiritual advancement. To those who are anger-prone, I advise replacing that fuming reaction with an affirmation that everything is just as it should be in God’s perfect universe.§

An initial focus on controlling anger and the other lower emotions and instincts is wisely built into the traditional concept of yoga as having eight limbs. The first limb is yama, which means restraint and is exactly what we have described—controlling our base emotions and instincts. Unfortunately, many modern yoga teachers and texts leave out this essential step that allows us to keep awareness above the lower chakras. Having sealed off the lower chakras, we are naturally drawn to be of service to others, to worship regularly and thereby deepen our devotion to God and to look within through meditation to experience our soul nature and eventually God’s indwelling presence as our very essence.§

The regular practice of these traditional spiritual disciplines not only keeps our awareness in the higher chakras, it also provides nourishment to our soul body. The soul body starts to grow within the emotional body. Gurudeva described this growth process by saying that the soul body grows like a child, fed by all of our good deeds. All of our service and selfless actions toward others feed that body. All of our working with ourselves to conquer instinctive emotions is food for that body, as it draws from the central source of energy. Finally, the spiritual body matures to the point where it becomes aware in the superconscious, intuitive mind, taking on more spiritual force from the Infinite. Ultimately, it takes over the astral emotional-intellectual body. And after moksha is achieved, it continues maturing in the inner worlds.§

PUBLISHER’S DESK • JANUARY 2013§

Advancing through Life’s Four Stages

______________________§

Applying the wisdom of ashrama dharma lends dignity and increasing purpose to every decade of life, but requires some new thinking§

______________________§

BY SATGURU BODHINATHA VEYLANSWAMI§

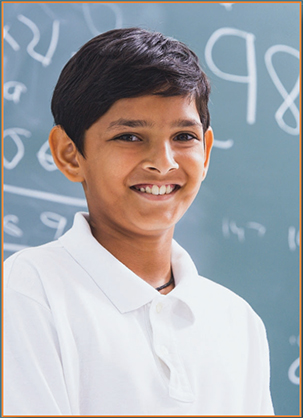

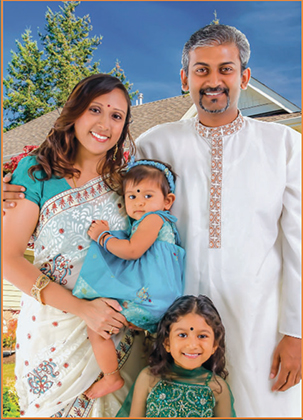

RAJIV’S LONDON CLASSMATES ARE A RAUCOUS bunch of teenagers, flush with vigor, carefree and oblivious to future responsibilities. They see him as a stodgy fellow—smart, handsome, likeable, but missing out on the fun. “You’re only young once!” Jeremy chides, “Why not party with us?” Rajiv lives in a different world, having learned from his parents that life is measured in four stages, and that we reincarnate again and again—so we are young many, many times. He saves his energies for the important stuff, building his knowledge and character in preparation for the family stage, which he will enter in his twenties. Disinterested in fooling around, he hopes to win the hand of a cultured girl with whom to share this lifetime and bring children into the world. Rajiv even looks forward to his elder years when, having fulfilled his duties, he will withdraw into his soul nature, the eternal Rajiv, seeking God Realization as he lives out this earthly tenure. Rajiv is convinced that each phase of life has a natural purpose, and that each is more rewarding than the last. For now, he chooses to study as hard as he can, and play a little in between.§

RAJIV’S LONDON CLASSMATES ARE A RAUCOUS bunch of teenagers, flush with vigor, carefree and oblivious to future responsibilities. They see him as a stodgy fellow—smart, handsome, likeable, but missing out on the fun. “You’re only young once!” Jeremy chides, “Why not party with us?” Rajiv lives in a different world, having learned from his parents that life is measured in four stages, and that we reincarnate again and again—so we are young many, many times. He saves his energies for the important stuff, building his knowledge and character in preparation for the family stage, which he will enter in his twenties. Disinterested in fooling around, he hopes to win the hand of a cultured girl with whom to share this lifetime and bring children into the world. Rajiv even looks forward to his elder years when, having fulfilled his duties, he will withdraw into his soul nature, the eternal Rajiv, seeking God Realization as he lives out this earthly tenure. Rajiv is convinced that each phase of life has a natural purpose, and that each is more rewarding than the last. For now, he chooses to study as hard as he can, and play a little in between.§

Rajiv’s plan is founded on Hindu tradition which divides an individual’s lifespan into four stages, or ashramas. This division, called ashrama dharma, is the natural expression and maturing of the body, mind and emotions through four progressive stages. It was developed millennia ago and detailed in scriptures known as the Dharma Shastras, highlighting the fact that our duties differ greatly as we progress from youth, to adulthood, senior years and old age. The Maitri Upanishad states: “Pursuit of the duties of the stage of life to which each one belongs—that, verily, is the rule! Others are like branches of a stem. With this, one tends upwards; otherwise, downwards.”§

Dr. S. Radhakrishnan, in The Hindu View of Life, summarizes: “The four stages—of brahmacharya, or the period of training, grihastha, or the period of work for the world as a householder, vanaprastha, or the period of retreat for the loosening of the social bonds, and sannyasa, or the period of renunciation and expectant awaiting of freedom—indicate that life is a pilgrimage to the eternal life through different stages.”§

This paradigm is as important and precious now as it was a thousand years ago, shared by all Hindus, regardless of caste or gender. However, the ancient descriptions may not translate perfectly to our modern life. Society has changed too much from how it was in Vedic times in India. For example, it would not work for all 50-year-olds to take up the life of a forest hermit, begging for their food. That would not be accepted by 21st-century society. In some countries forest hermits would end up in jail as homeless vagrants or trespassers, hungry ones at that. A certain amount of reinterpretation is needed to allow contemporary Hindus to utilize the wisdom of this natural evolution of life. As a starting point, let’s review the traditional descriptions.§

The first stage, or ashrama, is brahmacharya, student life, and those in this ashrama are called brahmacharins, “those of divine comportment.” It was usually a period of twelve years, from age seven or eight to age 19 or 20. The student lived in his guru’s home and learned scriptures, philosophy, science and logic. He was also taught how to conduct the Vedic fire ceremony. The brahmacharin was expected to follow a strict code of conduct, including celibacy, speaking the truth, gentleness in speech, physical austerities such as cold-water baths and eating sparingly at night. Serving the teacher and participating in the household duties were as much a part of his life as formal learning.§

The second stage is householder life, grihastha dharma, and those in this ashrama are called grihasthins. After returning to his family home, the student was expected to marry and raise a family, earning well by righteous means to provide for his wife and children, support his parents and give generously to charity. His religious duties included scriptural study and performing a daily Vedic fire ceremony in the home.§

The third stage is vanaprastha, hermit life, and those in this ashrama are called vanaprasthins, “forest dwellers.” Generally around the age of 50 or 55, after the birth of grandchildren, the Shastras explain, the householder is expected to hand over the responsibilities of the family to his children and retire to the forest. He may take his wife, if she is willing to share his life of austerities, or leave her with his sons. He is to continue the daily fire ceremony, observe continence and devote himself to contemplation on God, all to prepare himself for life’s final phase.§

The fourth stage defined in scripture is sannyasa, renunciate life, and those in this ashrama are called sannyasins. When the forest recluse felt enough inner strength to totally renounce all possessions and lead the life of an itinerant monk, he would embrace sannyasa, after entrusting his wife to the care of the children. In this stage he was to move about constantly from place to place, begging his food and devoting himself to japa, meditation, worship of his Deity and contemplation of scriptures.§

Four dynamic stages:

1) As a student, gaining knowledge in math, science and other fields; 2) supporting and raising a family; 3) as a grandparent, semi-retired, devoting more time to religious pursuits and community programs while guiding one’s offspring and their children; 4) as the physical forces wane, withdrawing more and more into religious practices.§

2. Householder, age 24–48 Grihastha Ashrama§

3. Senior Advisor, age 48–72 Vanaprastha Ashrama§

4. Religious Devotion, age 72 and onward Sannyasa Ashrama§

Looking next at how these ancient descriptions of the ashramas can be updated to better apply in contemporary society, my guru, Sivaya Subramuniyaswami, considered that in modern times each ashrama is a 24-year period, applying equally to men and women: brahmacharya being the first 24 years of life; grihastha extending from age 24 to 48; vanaprastha from age 48 to 72; and sannyasa from age 72 onward.§

The goals of brahmacharya remain the same today, but some of the details may no longer apply, such as living in the home of one’s teacher. Intense learning is still the main focus. Ideally, one acquires training in the profession he or she will follow in adult life. On the religious side, the basics of Hinduism are to be learned, along with memorizing mantras and conducting a puja in the home shrine, a practice that has largely replaced the Vedic fire ceremony in modern times. Students should be taught self-discipline, celibacy and other positive character qualities.§

The descriptions of the grihastha ashrama also stand the test of time. The main focus is on marriage, bearing and raising children, serving society through one’s career, earning income, taking care of elders and being charitable. Daily puja is conducted in the home, which ideally the entire family attends. Today the grihasthin is the primary teacher of Hinduism to his or her children, a duty the guru fulfilled in ancient times. This ashrama is a busy time of engagement in the world while advancing one’s family and profession.§

It is in defining the vanaprastha stage that need arises to rethink the old definitions. Becoming a forest dweller at age 48 is not an option for most people. Instead, my guru described this as a natural time to help and guide the younger generations as an advisor and elder. Brahmacharins and grihasthins can actively seek out the advice of vanaprasthins and draw on and benefit from their years of experience. For example, many Hindus in this age group mentor youth through community programs, teach Hinduism to children, serve on the boards of trustees or committees of temples, or fulfill leadership roles in secular nonprofit organizations. This is a time of giving back to the community what one has learned, while slowly retiring from professional and public life.§

The parameters of the sannyasa ashrama have also widened. A small percentage of modern Hindus follow the model of taking up sannyasa after retirement, renouncing the world and wandering among the thousands of sadhus and sannyasins of India, many of whom took up the mendicant path in their 20s and 30s. This pattern of elders taking up sannyasa is okay for single people, widows and widowers, and it still works in parts of India where society honors and cares for such holy men and women. But in most areas of the world, it is neither accepted nor understood.§

A number of Hindus turning age 72 have asked me what they should do differently in the years ahead. My advice is to simply intensify whatever religious practices they are already observing. If you perform a daily puja for 30 minutes, increase it to an hour. If you meditate daily for half an hour, increase it to an hour. If you go on pilgrimage for two weeks once a year, increase it to a month. Once these changes have become a firm habit, one would naturally be inclined to devote even more time to religious practices. After age 72, as the physical forces wane, is the time to turn within and withdraw from worldly involvement.§

My guru gave this helpful description of the third and fourth ashramas for modern times: “It is during the latter stages of life that family devotees have the opportunity to intensify their sadhana and give back to society of their experience, their knowledge and their wisdom gained through the first two ashramas. The vanaprastha ashrama, age 48 to 72, is a very important stage of life, because that is the time when you can inspire excellence in the brahmacharya students and in the families, to see that their life goes along as it should. Later, the sannyasa ashrama, beginning at 72, is the time to enjoy and deepen whatever realizations you have had along the way.”§

PUBLISHER’S DESK • OCTOBER 2012§

Sinner or Divinity?

______________________§

While some faiths view man as sinful by nature, Hinduism holds that our inmost self is the divine and taintless soul, or atma§

______________________§

BY SATGURU BODHINATHA VEYLANSWAMI§

IN TODAY’S WORLD OF GLOBAL COMMUNICATION, we encounter a multiplicity of views about the nature of man on a regular basis. At one extreme, each human being is inherently weak, imperfect, sinful and—without divine redemption—will remain helplessly so. At the other extreme, each human is inherently divine.§

IN TODAY’S WORLD OF GLOBAL COMMUNICATION, we encounter a multiplicity of views about the nature of man on a regular basis. At one extreme, each human being is inherently weak, imperfect, sinful and—without divine redemption—will remain helplessly so. At the other extreme, each human is inherently divine.§

This is one of the themes I talked about with Hindus in the Caribbean in August of 2011. I was told in Trinidad last year that this message—”You are a sinner in need of redemption”—is being promoted strongly in an effort to convert Hindus. I am often asked, “What should we say when confronted with this argument by strong-willed evangelists? What is the Hindu view?” Let’s explore three quotations from prominent swamis to define our perspective.§

The first is from Swami Vivekananda’s address to the World’s Parliament of Religions in 1893, in the bold manner in which he affirmed truth as he saw it: “Being and becoming are different aspects of the same reality and are only relative to our intelligence. Man has the promise and potentiality of divine realization, of spiritual perfection, and therefore is God in the making; for even his humanity is intelligible only if regarded as an individualized self-expression of God. It is derogatory to human nature, therefore, to attribute sin to man. Besides, God being the sole and supreme Reality, how could a foreign element like sin invade the sanctuary of being? The Hindus refuse to call you sinners. Ye, divinities on earth, sinners? It is a sin to call man so! It is a standing libel on human nature.”§

Swami Chinmayananda, founder of Chinmaya Mission, explained: “Man is essentially divine. But the divinity in him is veiled by the unbroken series of desires and thoughts arising in his bosom. A variety of these grades and concentration of these create the variety of human beings. To remove the encrustation of desires and thoughts, and unfold the divinity inherent in man, is the ultimate goal envisaged by the scriptures.”§

Satguru Sivaya Subramuniyaswami, my Gurudeva and founder of HINDUISM TODAY, gave a succinct description of our divine nature: “Deep inside we are perfect this very moment, and we have only to discover and live up to this perfection to be whole. We have taken birth in a physical body to grow and evolve into our divine potential. We are inwardly already one with God. Our religion contains the knowledge of how to realize this oneness and not create unwanted experiences along the way.”§

These opposite perspectives on man’s nature—sinner and divinity—were candidly juxtaposed during a 2012 interfaith panel discussion in Midland, Texas, at which I represented Hinduism. The issue arose as clergy from five faiths responded to the question “In your faith, is humanity considered a one family?” §

“There is a spirit which is pure and which is beyond old age and death; and beyond hunger and thirst and sorrow. This is atman, the spirit in man. What you see when you look into another person’s eyes, that is the atman, immortal, beyond fear; that is God.”§

Sama Veda, Chandogya Upanishad 8.7.3-4§

My answer was: “The Hindu belief that gives rise to tolerance of differences in race and nationality is that all of mankind is good; we are all divine beings, souls created by God. Hindus do not accept the concept that some individuals are evil and others are good. Hindus believe that each individual is a soul, a divine being, who is inherently good. Scriptures tell us that each soul is emanated from God, as a spark from a fire, beginning a spiritual journey which eventually leads back to God. All human beings are on this journey, whether they realize it or not.”§

The next speaker, Dr. Randel Everett of the Baptist Christian faith, put forth a distinctly different perspective. “The idea of the oneness of humanity—this is where Christianity would differ from some of the religions. We do believe in the oneness of humanity but that the oneness of humanity is that we are a fallen people. We do not believe that we are inherently good. We believe we are inherently selfish and self-centered, and that’s why we need to be rescued or redeemed—that Christ rescues us from the domain of darkness.”§

Looking more closely at the Hindu belief that man is not inherently sinful—rather, the essence of man is divine and perfect—a further question arises: “What is the Hindu view of sin?” Gurudeva responds in Dancing with Siva: “Instead of seeing good and evil in the world, we understand the nature of the embodied soul in three interrelated parts: instinctive or physical-emotional; intellectual or mental; and superconscious or spiritual.… When the outer, or lower, instinctive nature dominates, one is prone to anger, fear, greed, jealousy, hatred and backbiting. When the intellect is prominent, arrogance and analytical thinking preside. When the superconscious soul comes forth, the refined qualities are born—compassion, insight, modesty and the others. The animal instincts of the young soul are strong. The intellect, yet to be developed, is nonexistent to control these strong instinctive impulses. When the intellect is developed, the instinctive nature subsides. When the soul unfolds and overshadows the well-developed intellect, this mental harness is loosened and removed.”§

This understanding of man’s threefold nature—instinctive, intellectual and spiritual—explains why people act in ways that are clearly not divine, such as becoming angry and harming others. There is more to man than his essence or inner nature. We also have an outer nature. However, man’s actions, whether beneficial or harmful, sinful or divine, are all expressions of a one energy. That energy finds expression through the chakras, fourteen centers of consciousness within our subtle bodies.§

Many of us have seen the system for water usage at temples in India: a long pipe with faucets along its length from which many people draw water to wash their hands and feet before entering the temple. That’s a nice analogy to energy and the chakras. Our subtle body is like a pipe with fourteen spigots. Water is water; it can come out of any of the spigots. It’s still water. Energy can come out through any of our chakras; it’s still energy.§

Energy flowing through the higher chakras expresses the superconscious or spiritual nature. How do we control or direct our energy to keep it flowing through the higher chakras? Gurudeva used to say, “Energy goes where awareness flows.” We control our energies through consistent meditation and devotional activities in the home shrine, chanting, performing puja, attending puja and going to the temple on a regular basis. Listening to and playing refined music and performing traditional dance and other creative arts are also ways of channeling the energies through the higher chakras.§

Our regular activities determine how our energy flows. If we are engaged in spiritual pursuits, occasionally we might get up to the chakra of divine love. And hopefully we frequent the chakra of direct cognition, in which we are able to look down on our mind and understand what we like and don’t like about ourselves, and work steadily to change what we don’t. And we get into the chakra of willpower. These are the qualities we tend to manifest if we are engaged in regular spiritual/religious activities.§

If we are not elevating the energies, we are just living an ordinary life in the force centers of willpower, reason, memory, maybe fear and occasionally anger. If we see the flow of energy impersonally, then we can control it through the activities we choose to engage in.§

I like to say that we have an inner perfection and an outer imperfection. We can take heart in identifying more with the inner perfection, our soul nature, and realize the outer has its problems, which we can work on—and that is the purpose of our life on earth, to work on ourselves, to learn, evolve and ultimately know God. With this attitude, born of the belief in our divinity, we are more detached from our shortcomings and difficulties. It’s just energy flowing through our various chakras, more water flowing through one spigot or another. It is not who we are. We realize that we can control that energy flow. “Which spigot shall I turn on today? How do I want my energy to flow? Which negative habit do I want to improve today?” It all becomes easier to tackle because we look at it in an impersonal way.§

The concept of the fourteen chakras can help us put our failings into perspective so that we do not become discouraged by them. Shortcomings, such as occasionally being hurtful toward others, do not at all change the fact that our essence is divine. We can deepen our experience of inner divinity and overcome shortcomings by consistently following the various practices found in the Hindu religion. When we feel good about ourselves, we can more readily identify negative patterns and change them. If we have a negative concept of ourself, believing that we are inherently flawed and sinful, we are not in such a good position to advance on the spiritual path. And one thing we can all feel good about is that Hinduism assures us not only that we are not sinners, but that every human being, without exception, is destined to achieve spiritual enlightenment and liberation.§

PUBLISHER’S DESK • APRIL 2012§

Behold the Sacred Lotus Flower

______________________§

Progressing from our instinctive to intellectual to spiritual nature, our soul unfolds to resplendence like a beautiful lotus§

______________________§

BY SATGURU BODHINATHA VEYLANSWAMI§

THE HINDU VIEWPOINT IS THAT THE SEED OF Divinity is within everyone. My guru’s guru, Siva Yogaswami of Sri Lanka, had a down-to-earth way of expressing this idea. “See everyone as God. Don’t say, ‘This man is a robber. That one is a womanizer. The man over there a drunkard.’ This man is God. That man is God. God is within everyone. The seed is there. See that and ignore the rest.” It is definitely reassuring that there is no one who isn’t a divine being—that no one ends up in an eternal hell. Rather, it’s just a question of when an individual’s divine essence will express itself. It may be a few more lives before it does. After all, spiritual unfoldment is a slow and inexorable process.§

THE HINDU VIEWPOINT IS THAT THE SEED OF Divinity is within everyone. My guru’s guru, Siva Yogaswami of Sri Lanka, had a down-to-earth way of expressing this idea. “See everyone as God. Don’t say, ‘This man is a robber. That one is a womanizer. The man over there a drunkard.’ This man is God. That man is God. God is within everyone. The seed is there. See that and ignore the rest.” It is definitely reassuring that there is no one who isn’t a divine being—that no one ends up in an eternal hell. Rather, it’s just a question of when an individual’s divine essence will express itself. It may be a few more lives before it does. After all, spiritual unfoldment is a slow and inexorable process.§

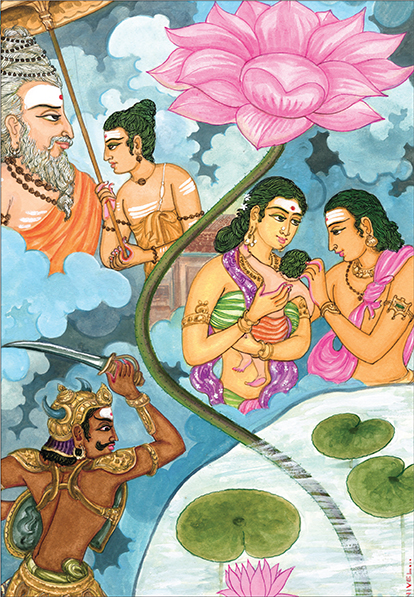

My own guru, Sivaya Subramuniyaswami, chose an insightful analogy for the process of spiritual unfoldment, which in Sanskrit is called adhyatma vikasa. He spoke about the lotus, how its seed starts in the pond’s dark mud. Its roots give rise to a stem that reaches up through the water into the air. From the stem evolves a bud, tiny at first, which grows into a flower that slowly opens its exquisite petals to the sun, the central nectar and pollen calling to the bees. Gurudeva compares that process to man’s nature and spiritual unfoldment. The mud is the instinctive mind. We all start out in the mud in one lifetime or another. In our early evolution we are crude and unkind. We tend to hurt other people and think more of ourself than others. Maybe we even end up in jail. We all start down there, in the roots, immersed in the darkness of the instinctive mind, crashing around like a bull in a china shop.§

Life follows life as we live and learn. Finally we get some control over our instincts and move up into the water, which is the intellectual mind. We become a thinking person, someone who is able to make decisions logically, someone who has basic control over the instinctive emotions so that when threatened he or she doesn’t automatically become angry and fight.§

At this point we are an instinctive-intellectual person, living partly in the mud of our animal nature, partly in the water of our intelligence. Such a person has no sense of God and the sacredness of life. The world is full of people like that, the atheists, materialists and existentialists. They are oblivious to the spiritual purpose of life, a purpose that goes beyond this incarnation.§

Then what happens? The stem rises above the water’s surface. It rises out of the water into the air, which represents intuition, our spirituality or some sense of the existence of God. We start to think about religion; we start to think about spiritual practices. Just being an instinctive and an intellectual person, just pursuing ordinary things, worldly pursuits, no longer satisfies us. But the bud is closed, yet to mature and open. The closed bud knows God is out there but has had no direct experience of Him.§

What causes the bud to open? Learning and maturing life after life, grace of enlightened beings, blessings of the Deity and spiritual practice. To open the bud, we have to consciously strive.§

Hinduism gives us religious practices that can be grouped into four categories. The first is simply good conduct, character building, charya. It is the foundation for deeper practices. Second is selfless service, seva or karma yoga—doing things for other people we don’t have to do. That’s how I define it. If in our place of work we do something for someone else out of the goodness of our heart, that counts as seva. Seva doesn’t have to be done at a temple or an ashram. If we go to work and only do what we’re paid for, no seva is taking place.§

The third category of practice is devotion, bhakti, which we express at a temple as well as at the temple we have in our own home. Maintaining a home shrine and worshiping there daily is an essential practice. The fourth is meditation, dhyana. Meditation is a bit advanced and requires a teacher’s help to do well at it. Most people I speak with say, “I try and meditate but I can’t control my thoughts.” They don’t have a teacher. They haven’t had someone personally explain the art of meditation to them. It’s an unusual person who can learn meditation by himself.§

Thus, the four categories of practice are good conduct, service, devotion and meditation. What happens when you take up some of these practices and perform them on a regular basis? The bud slowly opens. Your Divinity, which waited silently in the seed, blossoms.§

Many Western ideas and goals are based on the underlying attitude that there is only one life—or there may be only one life—so we had better do everything we can in this life. We had better achieve God Realization in this life, just in case. The Hindu attitude, based on the confidence that we live many lives, is: “I know I’m coming back; no rush. I will do as much as I can in this lifetime, and there will be ample time for further advancement.” The Hindu approach is to make spiritual progress in every lifetime—open the bud a little bit more. We are content to move forward by consistent practice, with whatever intensity we can sustain, without rushing, without fear of falling short. We rest assured that the seed of Divinity resides within each of us.§

Hinduism takes that idea one step further: eventually each of us will have the realization of God, our indwelling Self. The Shvetashvatara Upanishad states, “He who with the truth of atman, the soul, unified, perceives the truth of Brahman as with a lamp, who knows God, the unborn, the stable, free from all forms of being, is released from all fetters.” This is quite different from the concept, prevalent in Western faiths, that God is in heaven and cannot be experienced by those living on Earth. Gurudeva often spoke of the immediacy of this divine presence: “God is so close to us. He is closer than our breathing, nearer to us than our hands or feet. Yes, He is the very essence of our soul.”§

A. MANIVEL§

Spiritual evolution: The lotus, symbol of spiritual growth, rises out of the mud, up through the water and into full bloom. Our passage through many lives is similar. We begin with base, instinctive traits, such as violence, evolve to dharmic family living, and finally blossom as an awakened spiritual being.§

Back to our analogy of the lotus flower. When the lotus flower is sufficiently open, we begin living consciously in our spiritual or intuitive nature. Let’s ask the question, “What is it that makes spiritual progress? What is it that unfolds?” It is the soul. In thinking about spiritual unfoldment, it is helpful to understand the nature of the soul. We distinguish between the soul body and its essence. The essence is twofold: unchanging pure consciousness and transcendent Absolute Reality, beyond time, form and space. The soul body is a human-like, self-effulgent being of light which evolves and matures. This immortal soul body is referred to in Sanskrit as anandamaya kosha (sheath of bliss). It is the soul body that, like the lotus flower, unfolds. The soul’s essence is eternally perfect, identical with God.§

Just as our physical body matures from an infant to an adult, so too does this self-effulgent body of light mature in resplendence and intelligence, evolving from life to life, gradually strengthening its inner nerve system, progressing from ignorance of God to God realization.§

Gurudeva shared his own mystical experience of the soul body in Merging with Siva: “One day you will see the being of you, your divine soul body. You will see it inside the physical body. It looks like clean, clear plastic. Around it is a blue light, and the outline of it is whitish yellow. Inside of it is blue-yellowish light, and there are trillions of little nerve currents, or quantums, and light scintillating all through that. This body stands on a lotus flower. Inwardly looking down through your feet, you see you are standing on a big, beautiful lotus flower. This body has a head, it has eyes, and it has infinite intelligence. It is tuned into and feeds from the source of all energy.”§

There is another aspect to spiritual unfoldment. Choose the one Hindu saint, swami or yogi, living or passed on, who you feel achieved the greatest spiritual attainment. Now imagine and accept the idea that his or her attainment is your own potential. That is the surprising truth. The potential to achieve what anyone else has achieved spiritually lies within you to be manifested at some point in your future. Perhaps that thought will motivate you to put just a bit more effort into those spiritual practices! Visualize the lotus flower in full, magnificent bloom—that is the symbol of your full, resplendent spiritual potential.§

Of course, that potential only becomes practical when you strive. If you are serious in your seeking, ask yourself a series of questions: How am I applying the four kinds of practice in my life now? Good conduct? Seva? Bhakti? Meditation and yoga? Which areas are most in need of my attention and increased effort? What do I need to do in order to improve? Then do it.§